Trigger Warning: This review contains a discussion of suicidal ideation and self-harm.

Michael DeForge was one of the first artists that Annie Koyama ever published, so there’s a little bit of poetry in the fact that his latest comic, Stunt, will be one of her last. Released in September last year, Stunt is the story of a bodybuilding stunt double who evolves from being a stuntman to becoming a contractually obligated doppelgänger for budding actor Jo Rear. Over time, it becomes clear that Jo Rear wants to use the protagonist as his proxy to slowly destroy his relationships and career. This destructive behavior starts slowly, with dates with women other than Jo’s fiance, but as the book progresses, it becomes increasingly more complex and bizarre.

This performance suits the protagonist just fine; the work starts with a confession, “The fantasy was that one day I’d die in an accident. That’d be ideal. No one could blame me.” Jo Rear gives him the opportunity to turn that desire into reality. Given carte blanche to take Jo’s place, the protagonist has a way to manifest a suicide without it being his own.

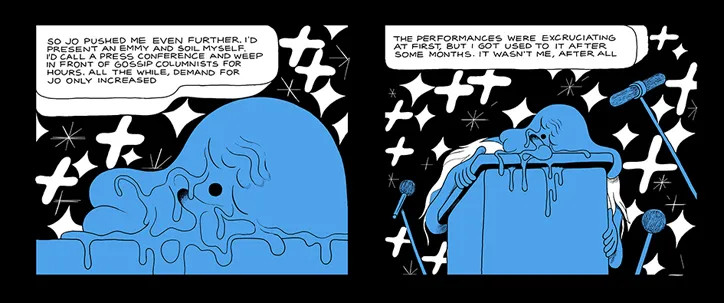

Stunt is an oozy kind of comic, full of sweat, blood, tears, and other bodily excretions. Dripping cans of energy drinks fill page after page. Crowds, likewise, are given an amorphous blob-like treatment, all big-eyed wonder, laughter without comprehension. DeForge is known for his expressive, undulating cartooning, but this book is tailored towards the goopy and the semisolid.

Stunt is also somewhat of an “uncomfortable” comic, something that you see both in the construction of the book (it’s far wider than it is tall) and in the way that DeForge situates his characters in his panels. As the book reaches its climax, characters seem crammed into the panels, obfuscating the body and removing a readers’ comfort of seeing a person unencumbered. DeForge intends to make his readers feel displaced and largely succeeds at this. The relative “closeness” of the physical body in this comic is juxtaposed with a narrative distance, as the protagonist narrates the story without any type of dialogue.

DeForge has used a particular type of narration throughout his history of comics-making, such as in his comic First Year Healthy from Drawn and Quarterly. Narration in DeForge’s comics tends to be linked with cognitive dissonance, as though what is happening on the panel is only being partly described. This is clearly the case in Stunt because what you see is a person harming himself as a proxy of another person, despite his cool and clinical explanation for what is happening. His employment as Jo Rear’s doppelgänger gives him the liberty to intwine his identity with that of his employer, to harm what he otherwise would not, destroy what he otherwise could not.

Yet, there’s an intensity to the desire for self-destruction in this book, so much so that it leads to actual physical intimacy in the comic, and although it might be a stretch, it feels like DeForge is ruminating on how suicidal ideation can, in its horrible way, be intoxicating. Having perfect control over how things are going to end, the ability to make the suffering disappear, the ability to make yourself disappear — these things are poison, but they often look like a cure. That power is wretched but inticing. You can get drunk on the idea of the loss of yourself. DeForge takes it a step further in Stunt; there’s a linkage between sexual release and the end of life in this comic that I find extremely troubling because it feels so bare and confessional. Stunt is at the height of its power at its climax, and reading it feels like acid dripping down your spine.

Stunt is clearly one of DeForge’s most intimate and revealing comics yet. Through interviews, DeForge has often talked about how he often obsesses over things. He is a long-distance runner, amongst other hobbies, and has talked about his mental health over the years. His struggles with suicidal ideation are clearly a large part of this work, and the idea of “beating a body into submission,” feels like an openness we don’t normally get from DeForge.

That openness leaves me staggering from the impact, because I have had that same thought so many times, struggled with the same darkness so many times. The slippery line and the visual chaos typical of Deforge’s work continue, here, unabated, and for the uninitiated Stunt will feel confusing and mysterious like much of the rest of his work. But never has DeForge’s work felt so honest or so connected. Never has it been so heartbreaking. I’m used to feeling like a detective when I read the comics of Michael DeForge. Stunt makes me feel like a voyeur – DeForge has laid himself bare in this work. Because of that vulnerability, it’s also his most affecting work. Stunt is hard to read, hard to even review because it feels personal. Stunt makes me feel seen.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply