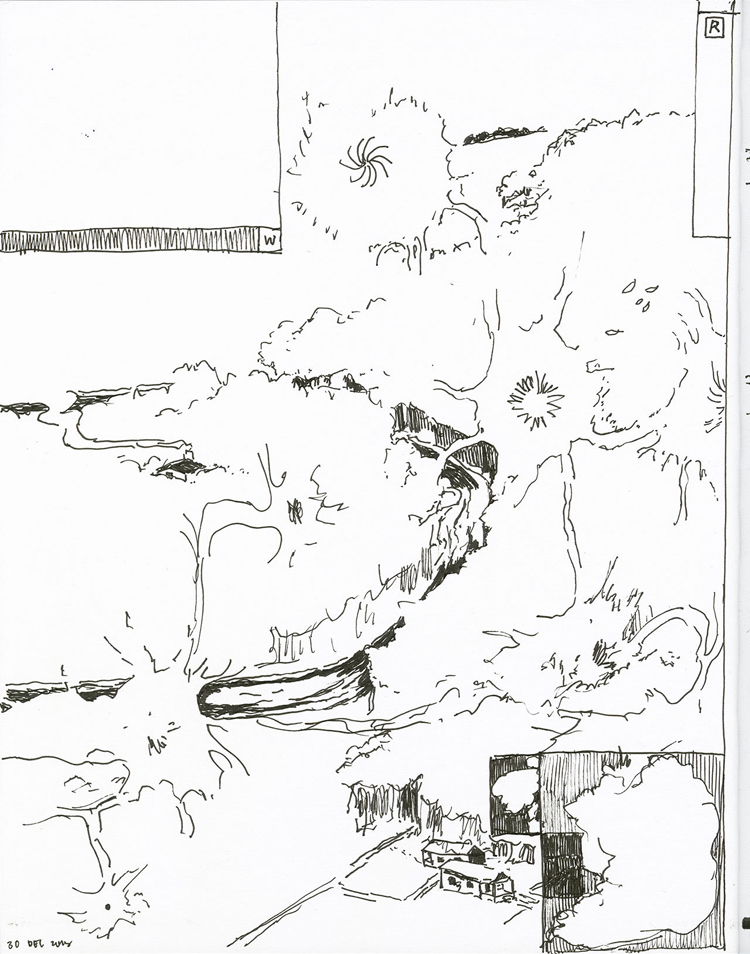

Paul Peng, 2019

When a piece of art looks like lines and shapes thrown against a page in a frenetic rush, how do you know it has meaning rather than just being random visual noise? When a comic is built out of abstract shapes and loosely connected words, how do you trust that it has a purpose behind it?

Much of how we appreciate narrative media is based on how much we trust that the person who has made it knows what they are doing. In comics, having a slick and well-designed visual style is a well-worn method to earn this trust. It feels like the artist’s intention is fully realized, and everything they are doing is what they meant to do. But in Art Comics, it’s a common practice to embrace messiness and ambiguity, and do away with the style of clean lines and clear shapes. So how do these artists maintain trust and show that there is intentionality to their work?

Intentionality is slippery because it seems on the surface like all that’s needed to make a very intentional piece of art is to just to intend to make something … and then make it. But if that old woman who botched the restoration of “Ecce Homo” actually meant to make the “Ecce Mono”, her choice to messily scrawl it over the original would still lead us to assume that her efforts were intended to restore the piece. Likewise, if someone intentionally tried to tell a traditional story but with a unique structure to it, we might say it has “structure problems” because it would be interpreted as trying to follow a more well trod structure and failing. Intentionality isn’t as simple as what the artist intends, it’s about what the audience thinks the artist intends. It’s not about the actual intention, it’s about the intention that a work implies.

Intentionality also isn’t just a matter of what the intent seems to be, but also how well that intent is executed. Something doesn’t look “intentional” just because it looks like there’s intent behind it, it looks intentional if it seems that the artist had something in mind when they created the piece and followed through successfully on it. Or, in narrative works where the full nature of the work isn’t obvious halfway through reading it, if the artist seems competent and in control enough that their intent will clearly be fulfilled.

Left Erin Curry, Ley Lines Poem to the Sea; right vaguesteph, 2019

So using this lens to view things, what are Art Comics and what intentions do they communicate to the reader? Art Comics have always been tricky to pin down because they share such porous boundaries with Poetry Comics, Experimental Comics, and Abstract Comics. But, on a basic level, Art Comics are comics influenced by the art world more than they are by the world of design. For example, an artist like Erin Curry’s comics pages all feel as if they could easily be hung in a gallery as abstract expressionist art.

People tend to know what to expect an abstract expressionist art piece to look like and, at least, vaguely the ideas behind it. For example, some works are not supposed to look like anything in particular, they are created to evoke a feeling. The audience’s familiarity with this stylistic lineage helps them know what the work intends to be. While many other Art Comics artists other than Curry may have less easily identifiable influences, they generally exhibit stylistic touches that evoke this “art worldiness” enough that the audience knows that the work is intended to be met with thoughtful contemplation rather than the entertainment or drama of other comics.

This art world context also gives a path for how Art Comics artists prove to their audience that they have the control and competence necessary to meet their intentions. A comic artist like vaguesteph knows how to speak about ideas, how to use the correct jargon and terminology, and how to put off a persona of purposeful ambiguity. These are the same tools used by certain sorts of gallery artists looking to convince rich people to buy some art, and they function just as well to assure Art Comics readers that they are in good hands, that the comics artist will be able to follow through on what they intend to do.

It’s one thing to earn that trust in textually explicit works, where you can drop a paragraph from a feminist writer into your work as vaguesteph occasionally does. But how does it work with an artist like Paul Peng who communicates his ideas visually and tonally? Like vaguesteph, he creates works about the selves we create in the online world, and he has a strong thematic coherence to his work. Paul Peng draws a sexualized fantasy self, but he, as an artist, always feels apart from his creation, observing it as a sort of alienated transcendence. This distance functions to create a persona of purposeful ambiguity, and his thematic coherence functions as a claim to intellectual expertise. Again, these are some of the same tools people use in the art world to communicate their competence and control in meeting their intentions.

Left Mickey Z, Lovers Only #2; right Alyssa Berg, Open Letter to Sleep

While many Art Comics pull on art world influences, there is also a strong contingent within the genre that developed from the punk scene and DIY zine culture. Punk is very much about the democratization of art, about breaking down authority and gatekeepers, so the frenetic messiness of a Mickey Z comic for example, or the wobbly simplicity of an MJ Robinson comic, doesn’t need to be proven to be competent or in control in the same way as other styles. The cultural values associated with punk as a scene and a movement obviate most of the need for it.

Likewise, the Santoro school’s signature “Santoro grid” can be seen as a way for an artist to communicate control and competence. It is a formal element that Frank Santoro suggested to be used by basically all people vaguely within the Art Comics sphere, and it serves as a clean and simple design element to contextualize the messiness of other elements on the page as an intentional choice. The grid is agnostic as to the intention of the art itself; rather, it serves to bolster the trust readers have in the artist’s ability to meet their intentions.

Similarly, the almost pop song simplicity of Alyssa Berg’s emotional narratives serves to counterbalance her organic and intense art. Her comics are sometimes framed as letters, filled with pain and yearning, and, though they are usually poems, they are very direct. They’re always about emotions, about wants, about needs. The intention that comes across in her work is one of cathartic release, communicated through raw, textured art that gives weight to the emotion. Like with punk influences, this cathartic intention is perceived as fulfilled through messiness. And, like the Santoro grid, her directness shows competence and control through its simplicity and clarity.

Left Warren Craghead, Ink Brick #8 | right Maré Odomo Internet Comics #2

Trust in an artist’s ability to meet their intentions is also sometimes earned through giving the reader small moments of recognition. The way that Warren Craghead breaks up letters across the page into almost puzzles to be put together makes the reader go through a process of experiencing a confusion that pleasantly resolves itself into understanding. Likewise, when Maré Odomo crosses out words in a sentence to give a sense of what was said and what was almost said (or what was really felt), it creates something for the reader to decode and find meaning in. When the reader searches for clarity, there is always the possibility of failing to find it, that which seems a puzzle might just be a failure of the artist to communicate effectively. So when the reader searches and finds something that makes sense, or is meaningful, the artist has proven to them that there is a competent hand guiding the reading experience, that the artist is skilled enough to meet the intention of the piece.

This isn’t meant to be a comprehensive list of Art Comics tricks, but to give some idea of how artists communicate intentionality without influence from the world of design. Design as a discipline is entirely about ease of communication, yet Art Comics often subvert design principles, while still longing to communicate with an audience. This seeming contradiction is the crux of why intentionality in Art Comics is interesting to explore.

Art Comics is an especially varied genre, filled with experimental and ambiguous techniques that seem like they could sever the trust between artist and audience. So pointing to where it works, where communication happens, is illuminating. It reveals viable paths for artists to follow and, in doing so, relieves the necessity to rely on tried-and-true methods and opens doors to new and original ways of conveying intent.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply