There was a twitter dust-up, at the beginning of the apparently interminable early summer of the pandemic, about the political meaning of history. While students and teachers of history have long known that the interpretation of events is subject to legitimate disputation and reconsideration, it’s easy to see why, in a moment when the US government disputes even the most rudimentary conventions of truthful reporting and historic accuracy, attachment to an unimpeachable chronicle of events would appear to be uniquely valuable and threatened. On the other end of the spectrum, recent controversies about the heroic effort to remove and destroy Confederate and other racist monuments in the United States remind us that, too often, “teaching” or remembering history tends to take the form of a single calcified meaning, generally in the equestrian vein. The victors of the long durée, those who preserve “the past” as a means of securing the power structures of the present, benefit from a resolvedly static approach to history nearly as much as they benefit from the particular history they have decided to memorialize. The construction of a range of inexpensive Confederate statues across the country in the 1920s attests to the power of memory as a power claim in the public sphere, mounting the memory of the Confederacy on a resplendent, or at least cheaply made and ostentatious, horse and setting it up in front of the courthouse.

Careful and thorough historiographical analysis, to explain how and why certain narratives become useful to whom, is one way to fight this tendency. Kinetic historiography, or just pulling the damn things down yourselves, is another. A third way is to contest the affective structure of history writing and offer less settled, arguably more humanistic, alternatives. It is this third option that is perhaps best suited to popular art, a venue that sometimes prefers a phenomenological claim to an epistemological one. This is not to say that such representations cannot make arguments; indeed, they necessarily must, since to represent history is to opine on it. Rather, and here I follow Walter Benjamin, they change the focus from the established or desired meaning of a historical event, determined retroactively, to the moment that meaning was far from settled — when it was “alive” as a scene of possibility and change. From this position, they can reopen the case, contest the meaning and emphasis of the historical record, and remind us that our own historical moment is still changeable — because, as Benjamin warns us, even the dead are not safe from the enemy if he is victorious.

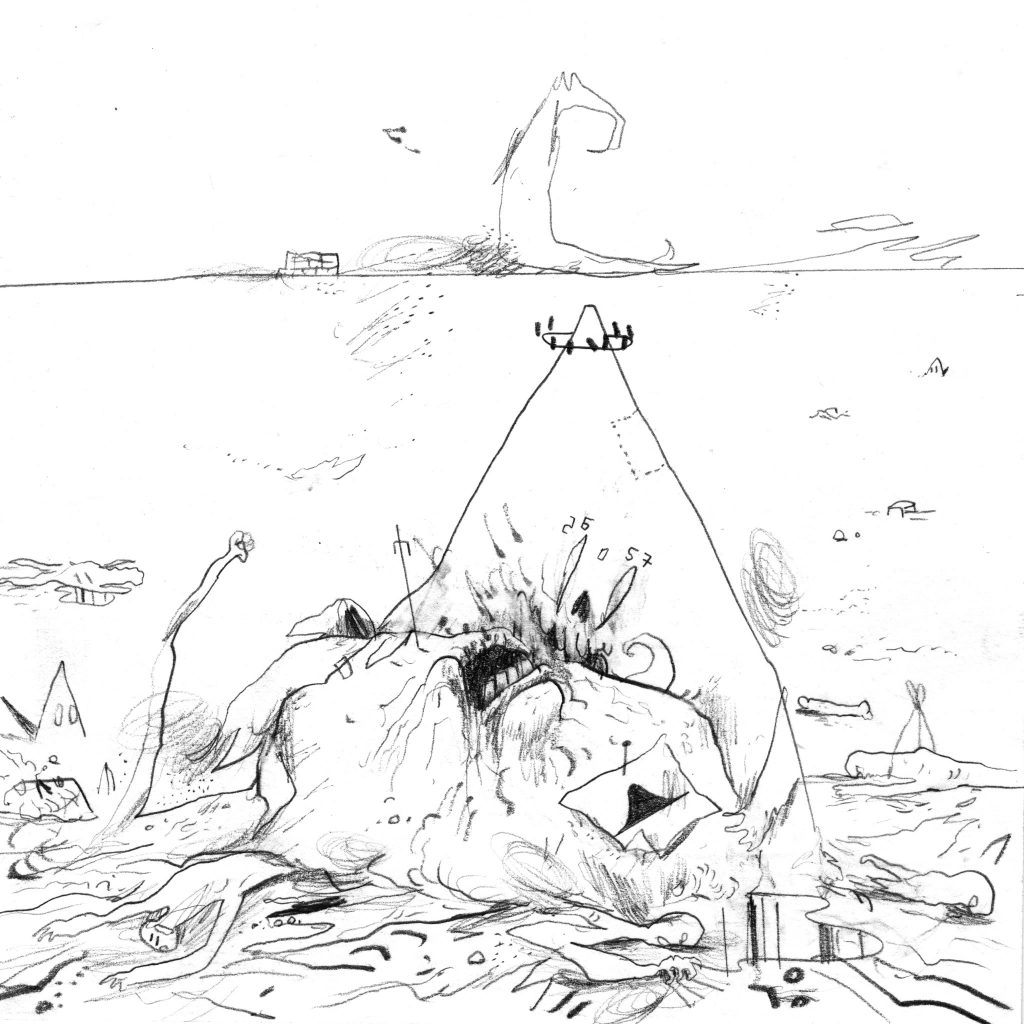

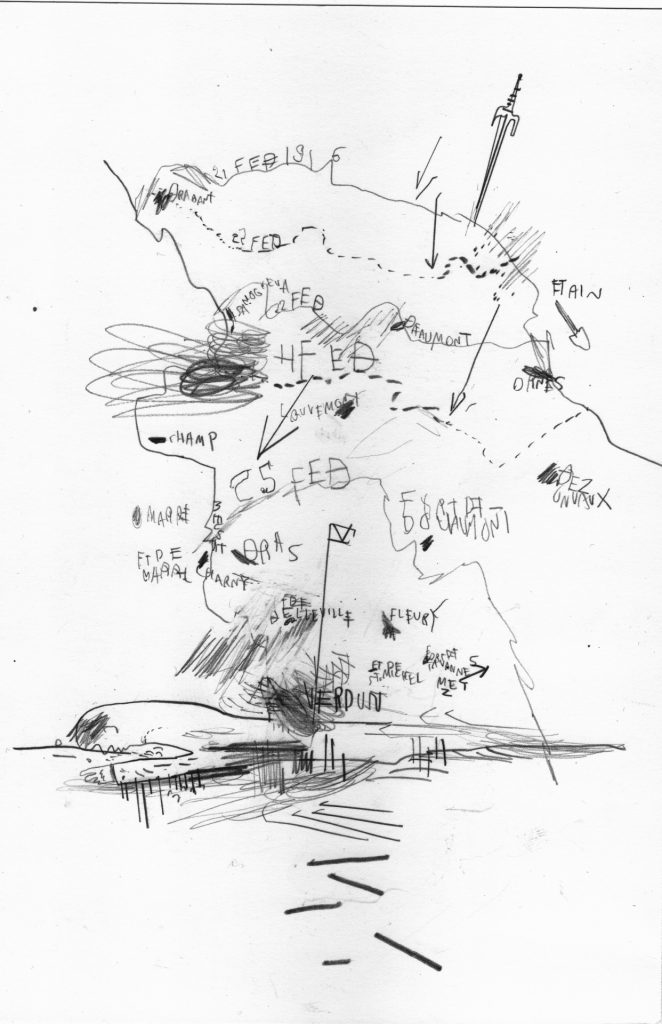

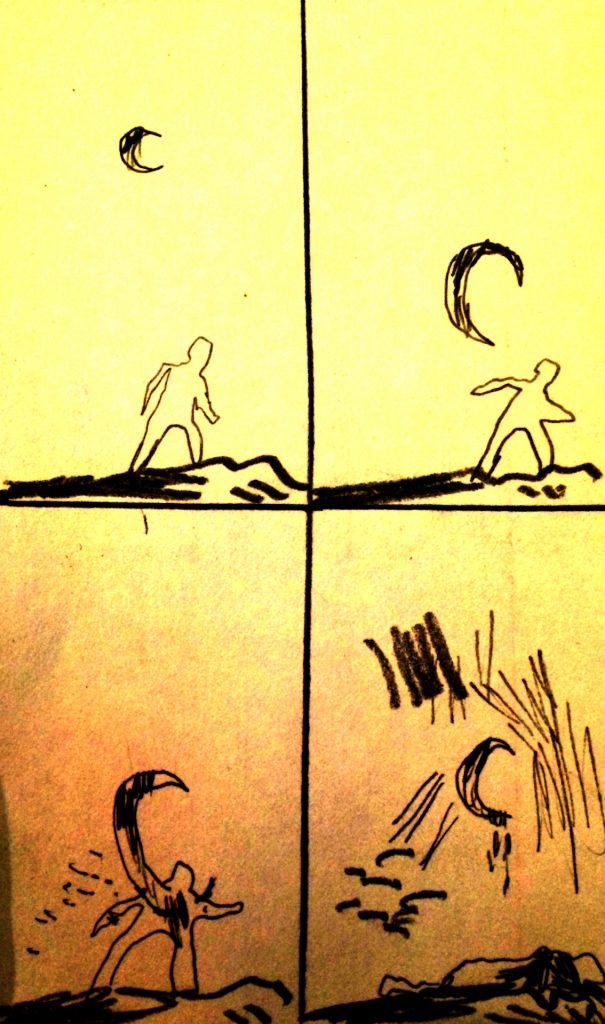

Warren Craghead’s recent work offers one model for such imaginative witnessing of the past, using his significant power as an illustrator and cartoonist to revisualize past and present catastrophes with an eye alternately outraged and sympathetic, but seldom fatalistic. His “live drawing” project invites us to reinhabit and rewitness historical events as they move from ongoing situations into defined events — without ever losing sight of the trauma and urgency of the situation itself. Two completed projects, La Grand Guerre, subtitled “live-drawing World War I, one hundred years later,” and Medz Yeghern: Drawing the Armenian Genocide are exercises in visualizing world memory which reintroduce experiences of temporality and sequentiality to history. His ongoing TrumpTrump documents the Trump presidency. For each project, Craghead’s process has been similar. He draws a single page or illustration per day for several years, starting on a historically significant date. La Grand Guerre was illustrated between 2014-2016, Medz Yeghern 2015-2019, and each has start dates corresponding to the centennial commemorations for the start of each event. While neither historical project lasted as long as the event they depict, Craghead’s choice to work temporally and sequentially contribute to our felt understanding of these events in their ongoingness, rather than their retroactive meaning as events. Because both projects are hosted on Tumblr, it can be a little bit difficult to revisit the project in order, to say nothing of “as intended.” Still, reading through the hundreds of images even in a haphazard fashion impresses one with the suitability of Craghead’s melancholy and modernism inflected forms for works of mourning, and with the gravity of attention and commitment demonstrated in working on a project of such scale and duration.

These historical projects are acts of imaginative witnessing because they operate at the nexus of testimony and experience or performance. Craghead combines research, including visual research into photographs and other traditional means of seeing the past “as it happened”, with a durational component, imitating the temporal experience of seeing a catastrophe unfold through the dailiness of his projects, for himself and for his readers who follow along via social media. What feels most urgent about Craghead’s recent projects is the time committed from his own life, which reminds me slightly of performance artwork which emphasizes endurance or measures time through presence, like Abraham Poincheval who lived inside of a rock for a week, or, my favorite, and a much more relevant intervention, Joseph Beuys’ “I Like America and America Likes Me.” It is moving to look at the compilations of Craghead’s work, via Tumblr archive or flipping through the smartly bound, toothily printed, and only slightly expensive book from Retrofit, and see the commitment to witnessing as an action, and the drawing as a document of that witnessing. The drawings are a trace of several levels of presence and remembering. Most immediately, of Craghead’s hand. Following Hilary Chute’s astute reading that the trace of the autobiographical comics artist reminds readers of the presence of the real person who made the work and who describes the events in it, in Craghead’s memory performance, the trace of the artist is a marker of the time and attention, which is to say care, that Craghead has directed towards the subject. Like the graphic novels that Chute focuses on, Craghead works across several registers of time to demonstrate and comment at the same time.

Craghead invites us to see the past, through his representations of events and images as well as his highly visual approach to lettering, allowing him to incorporate testimony through text but not only as text. The work of selecting an image or a piece of text to recreate or to comment on through his visual approach to the subject, and the labor involved in producing a drawing every day, force a reconsideration of historical time and importance. The somewhat conventionally fixed meaning of a historical event is pushed out of alignment with conventional historical narratives and back into the temporal experience of a tragedy unfolding, as it was when it was preventable or changeable. Yet historical meanings are not as conventionally fixed as such an analysis might imply. For example, genocide denial, including of the Armenian Genocide, continue and even increase alongside rightwing extremism. Revisiting the durational experience of historical events, though, acts a rebuke to such denialism, albeit one that will mainly preach to the converted.

With TrumpTrump, a daily drawing project, 2016-present, Craghead introduced a new duration project. Unlike Medz Yeghern and La Grand Guerre, there is no need to restore a sense of temporality on events unfolding in the immediate present, since Craghead is working in real time, generally drawing events from the day’s news cycle. TrumpTrump is thus a more traditional act of witnessing, as Craghead makes his selections from events he is seeing through the press or Twitter, rather than trying to blow the dust of history off historical documents. TrumpTrump invites us to ask why it is necessary to think historically about this unfolding tragedy, and what it means to engage in witnessing as an experience of duration, rather than documenting and retelling incidents.

Craghead’s intervention into historical imagining is visual as well as temporal. In La Grande Guerre, Craghead uses representations of events, objects — like gas masks or goggles — diary entries, and more to create the texture of life during wartime. These varied subjects are typical of his witnessing or memory projects, and differentiate his work from projects which simply relay historical events, like any of the live tweeting history projects. The opposite of the grand monument or the phallically triumphant obelisk, Craghead’s work tends to render figures fairly sparsely, emphasizing the texture and emotion of his mark making. He also draws on the visual vocabulary of experimental concrete poets, like Appollonaire, and associated Dada, Expressionist, and Surrealist artists, whose work often described and responded to the extreme political conditions and violence surrounding the outbreak of and resulting trauma from WWI. For a more comprehensive gloss of Modernism in the early 20th century as it relates to documentary work on violence and war, I recommend Hillary Chute’s overview of the history of artists as witnesses in chapter one of Disaster Drawn. As well, briefly mentioning Kathe Kollwitz, who Craghead cites as an influence, and whose scratchy, heavy linework in support of strong shapes and clear forms in lithographs and woodblock prints resonates with Craghead’s own style, might suffice as a starting point to understand how Craghead’s visualization work contests any fixed meaning of the heroic past and instead reinscribes living affect.

Kollwitz’s work documents the suffering of women, children, and workers under war and poverty through highly textured work emphasizing expressions and postures of mourning. Her linework, like most Expressionist work, is meant to describe or represent the experience of an emotion. Raw edged, serious, and dark, it looks like grieving. For one year, Craghead drew a single image every day, a redrawing of the photograph by Near East Relief that he captioned “Woman with dead child outside Aleppo,” which bears a glancing resemblance to Kollwitz’s “The Parents” in style and form, and which offers a basis for comparison. This is not to say Craghead’s work is derivative of Kollwitz’s, but rather the comparison allows us to read both projects more attentively.

The figures in “Woman with dead child” look slightly different every time Craghead draws the image, revisiting the same site of grief and reexperiencing it each time, but what remains consistent is the textured, often sharp and sharply angled linework, with scribbles — in the sense of quick and furious mark making, not in the sense of carelessness — taking the place of hatching or more traditional cartoon draftsmanship to create volume and form. While Kollwitz’s lines invoke furious emotion, they also are particularly suited to the method for indicating volume through her medium, the woodblock print, which must be scraped and gouged to make an imprint. Craghead’s work, which looks like it’s done with a graphite pencil, similarly offers a kinetic document of seeing and responding, what I am calling a creative witnessing of the past, but with a wider range of tones and a heavier emphasis on the individual line than on the overall balance of positive and negative space. This is what allows him to create the often delicate and spare forms of figures, objects, and letters, which contributes to the melancholy feeling across much of his work. Textural and emotive rather than documentary, Craghead’s distinct spidery lines and use of graphic textures contribute to the palimpsestic feeling of his work.

So, too, do the lettering effects for which Craghead is justly but, in my mind, never sufficiently lauded. Words scramble and float, unsettling the conventional rigidity of the picture plane which persists in conventional comics, despite the necessary fluidity between word and image in a visual medium. Rather than cordoned off in word balloons or narrative boxes, Craghead’s letters permeate the boundaries between figure and grounds, subject and context. Words often start just inside a figure and split off towards the outside, producing a visual fracture and requiring careful attention to decipher the correct reading order. Because much of his text in his historical witnessing projects is found testimony, I find this creates a sense of haunting, or of a blurred, ghostly, ambiguity as to what constitutes a presence on the page and what constitutes a representation. For a project of witnessing and remembrance, the ambiguity and attended feelings of melancholy is central to its efficacy. When Craghead relies more heavily on concrete symbolism, more difficult questions about conventional versus personal meaning emerge.

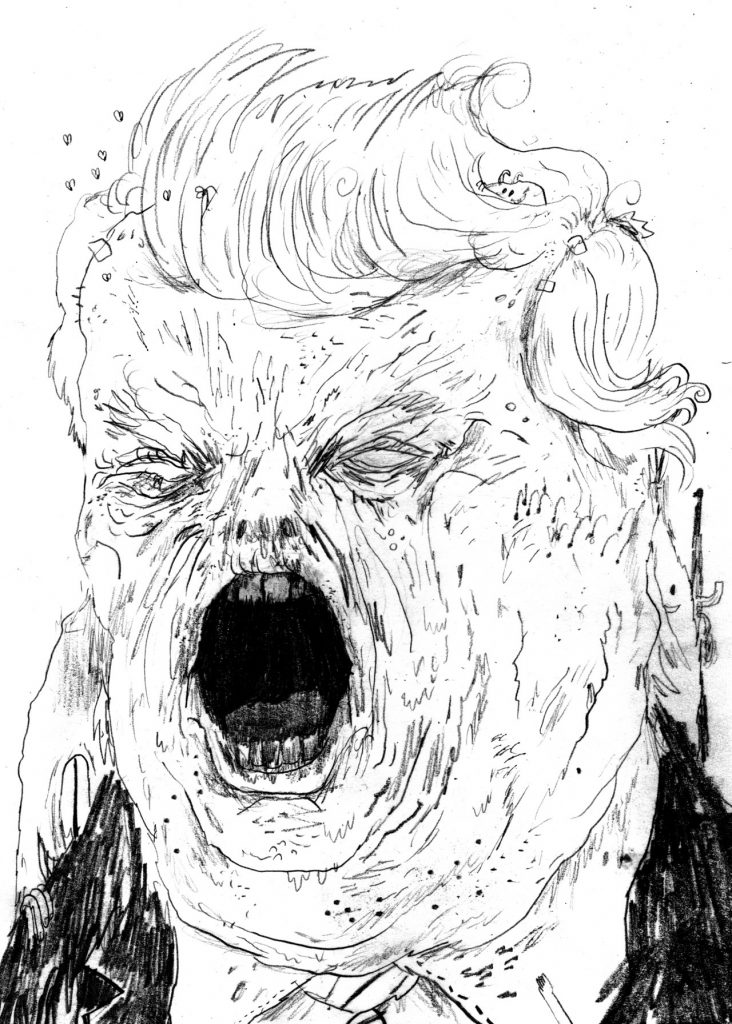

In Medz Yeghern, Craghead experiments with a range of visual shorthand, not least of which is a sword with a crescent moon, which suggests a possible resort to caricaturing through associations of e.g., Arab Turks with scimitars, instead of a more thoughtful engagement. This use of shorthand continues in TrumpTrump, where Craghead starts from a fairly rigid visual vocabulary. The sparse early drawings are littered with bitter, coded, jokes which can sometimes send one on a game of ‘I Spy” to find all the hidden skulls, spiders, slices of pizza, etc. Standout examples include a sword labeled “blood and soil” in Craghead’s distinct floating text, caricatures of bit players in the Trump regime who cling to him or lurk behind him (then speaker of the house Paul Ryan as a Musters-looking vampire, vice president Mike Pence with a two bit halo taped above his oviform head), and, perhaps most distressingly, little tiny Klan hoods with dot eyes and tiny feet. The little Klansmen peek and play around the corpulent, tiny-dicked mound of Trump’s form, a heaving bulk always pictured with a little pool of piss leaking out of it.

Craghead has cited Dada-affiliate painter-cum-satirist Otto Dix as an influence, and while there’s some plastic resemblance in Dix’s trauma informed etching series Der Krieg (Not to be confused with Kollwitz’s Krieg), I assume the more direct influence on TrumpTrump is Dix as a social critic. Like other Dada and Expressionist artists, Dix pushed form in his caricatures to criticize the parasitic excess of the ruling class and to describe the physical and spiritual deformations of the subordinated. We live, however, in a quite different regime of bodily politics than that of Weimar Germany– to start, the all-volunteer army and the drone strike have made it so that many of us avoid prolonged contact with those missing a big chunk of their face because they got blown up. In fact, the very problem of how easy it is to obscure or hide the subjects of violence during the 24 hour news cycle is part of what a witnessing project at least potentially responds to. Accordingly with this change, the efficacy of the grotesque caricature to describe abhorrent behavior runs into serious questions about the tendency of grotesquerie to draw on ableist shortcuts. Critics regularly question the use of this kind of shortcut in political cartoons (and Twitter hashtags) lampooning Trump — incontinence, a small penis, or obesity as descriptive of moral shortcomings invite questions about how society sees and treats obese people, people with small penises, or people with bladder disease.

Is the grotesque therefore outmoded? I don’t think it has to be, nor are all of Craghead’s visual moves quite so direct. The cuteness of the Klan robes, distilled to an almost Mad Magazine looking cartoon triangle, is provocative and much more difficult to read. Do they look like that because Trump’s administration is a playground for white supremacists? Because white supremacists are getting cute, so to speak, with the new regime? Is their deceptive innocence supposed to register as harmlessness, as if they’re small fish swimming in the large and poisonous pond of the Trump regime, or is it a way of sending up the way the regime itself treats them as innocent, “very fine people?” Can rendering something obviously wretched as insidiously visually appealing, the figurative opposite of the monstrously inflated Trump figure, constitute an equally effective visual critique?

No matter how one answers these questions, and I suspect it’s personal to each reader, it’s uncomfortable to dwell on this miniaturized form of one of the most famous violent groups dedicated to racism to have ever been active in the United States, so it was almost a relief to me when, about halfway through the first collected volume, they expanded in size, grew veiny staring eyes in place of flat cartoon dots, and developed shaky outlines, more in line with how the rest of the visual evils in TrumpTrump look. Probably the weakest early drawings include Putin as a Russian bear, which feels very Cold War redux, like an Oliphant cartoon got lost on its way to the syndicate office, and some of the funniest are of Jeff Sessions as a wrinkly cross-eyed elf with a swastika on his head, so obvious menace or disgust seldom seems not to work as well for Craghead in this project as contempt or slyness. It’s hard to argue for that mode as conveying horror, but it’s also hard to argue that ‘conveying’ horror is fully necessary or adequate to our moment. We’re all horrified, living under conditions of perennial horror.

Questions probably need to be answered about the work of “witnessing” in the era of up-to-the-minute reporting. The circulation — really the virality — of images of trauma and death, particularly Black and Brown trauma and death, is a constant. Witnessing in itself doesn’t constitute a politics, as much as we might wish it to do so. Explanations like ‘raising awareness’ fall short. As Zoe Samudzi puts it in her essay on history and memory of genocide in and beyond Armenia, “Against(?) Empathy,” “who doesn’t know about police violence, who doesn’t know about camps on the southern border of the United States?” Theorists like Susan Sontag, in Regarding the Pain of Others, and Jacques Ranciere in The Emancipated Spectator, have addressed the problem of images of atrocity. Even if we assume that these images work as intended to create disgust, grief, fear, and horror, they don’t necessarily also produce desired actions or outcomes, not least because the gap between feeling and organizing is pretty stark. That gap between scope of feeling and scope of felt efficacy can lead to despair. Similarly, if TrumpTrump or Medz Yeghern or La Grande Guerre merely depicted horror, I don’t think they would be particularly effective projects. Instead, Craghead shows us his looking at horror, his project of carrying the weight of engaging, every day, with historical memory and present catastrophe, and the work challenges us to find our own way to carry the same weight, and, more urgently, to contest that the past or present are closed books, beyond intervention. Looking at these events as unfixed, revisiting the ways they could have been or still could be otherwise, invites us to contest the present actively and fight for the meaning of the past.

As TrumpTrump expands over four years, from the Trump rise from nomination to presidency, and now to a second election cycle, the urgency of different kinds of claims about “witnessing history” have shifted. Many projects about Trump urge that readers “not look away” or affirm that “this is not normal,” but what happens regularly becomes a kind of normal, and Trump was never far from the ordinary, garden variety, white supremacy of the United States anyway. It was this matter-of-factness about the ordinary state of society that makes much of the art Craghead draws on so effective, even removed from its original context of WWI and the Weimar Republic. Where I think Craghead’s work intersects is the meticulous observation of time as a means of measuring historical experience during crisis, a time when we all seem to be losing our grip. Witnessing becomes about the scrupulous act of making work, each day, and the compound effect of the many, many pages — the, to borrow crassly and perhaps unfairly from Walter Benjamin, unbroken chain of catastrophes which constitute not just this presidency, but every presidency. Each of these projects is a powerful body of work in itself, and reading them together, as projects in creative empathy and historical thinking, rewards readers willing to practice the same patience Craghead did in making them.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply