In my Best Comics of the Decade essay, I suggested a new genre/concept, Navigating Space Comics, to illustrate some of the most intriguing bunch of contemporary comics. Both the name “Navigating Space Comics” and the concept refer to “Navigable Space” from Lev Manovich’s influential The Language of New Media (2001).

In the book, Manovich proposes two New Media (computer, internet, smartphone, etc.) specific forms: Navigable Space and Database. For Manovich, the most notable example of the Navigable Space is the video game. For video games, the user navigates the game space to accomplish specific missions to advance to the next stage of the game. Computers in general are also an example of the Navigable Space; the user navigates the screen and the window space with the cursor (mouse). In smartphones, the user employs their fingertip to navigate the screen. In all of these examples, the narrative and/or the journey of the user depends on their navigation.

Although the idea of the journey (i.e. navigation) has been an integral part of narrative and narratology since ancient Greece, for Navigable Space, the importance of space and navigation are much more prominent. Navigable space is to play in and with. Applying this concept to comics, Navigating Space Comics are comics that are interested in exploring space instead of characters, emotions, or plot development. For Navigating Space Comics, space itself is a topic, subject, or motive, more than a background or environment. The narrative is the sum of interactions with space. The narrative propagates as characters navigate spaces, not as characters/emotions/plots evolve.

How Navigating Space Comics Work: Spatializing by Navigating

In his field-shaping book The Practice of Everyday Life (1980), French philosopher Michel de Certeau posited that the act of walking “actualize[s]” and “invent[s]” space. Walking “spatialize[s].” The walkers “cross, drift away, or improvise, transform or abandon” the ordered and already built place. They “weave places together.” Thus, they “articulat[e] a second, poetic geography on top of the geography of the literal… or permitted meaning[.]”

de Certeau describes the mechanism of this “spatializing by walking (i.e., navigating)” by correlating the act of walking and the resulting space with the act of writing and the written text, and even “with the “hand” (the touch and the tale of the paint-brush) and the finished painting (forms, colors, etc.)[,]” This comparison fits deftly with the Navigating Space Comics.

Expanding the analogy, de Certeau compares Synecdoche (from rhetoric) with walking, saying “the long poem of walking manipulates spatial organizations, […] It inserts its multitudinous references and citations into them (social models, cultural mores, personal factors).” Furthermore, de Certeau parallels Asyndeton (again from rhetoric): “in walking it selects and fragments the space traversed; it skips over links and whole parts that it omits.” “Through these swellings, shrinkings, and fragmentations, through these rhetorical operations a spatial phrasing of an analogical (composed of juxtaposed citations) and elliptical (made of gaps, lapses, and allusions) type is created.” It is intriguing that comics also comprise these “juxtaposed citation,” fragments of space and gaps.

Finally, de Certeau contrasts concepts of place (lieu) and space (espace) to delineate the mechanism of Spatializing by Navigating (walking) more. He argues that “a place (lieu) is the order in accord with which elements are distributed. …A place is thus an instantaneous configuration of positions.” A place is how things are positioned. On the other hand, “A space (espace) exists when one takes into consideration vectors of direction, velocities, and time variables… Space occurs as the effect produced by the operations that orient it, situate it, temporalize it, …in relation to place, space is like the word when it is spoken, …when it is caught in the ambiguity of an actualization, …situated as the act of a present (or of a time), and modified by the transformations caused by successive contexts.” “Thus the street geometrically defined by urban planning is transformed into a space by walkers. In the same way, an act of reading is the space produced by the practice of a particular place: a written text[.]” In the same way, an act of comics reading is a space produced by the practice of particular places: panels.

Contemporary Navigating Space Comics

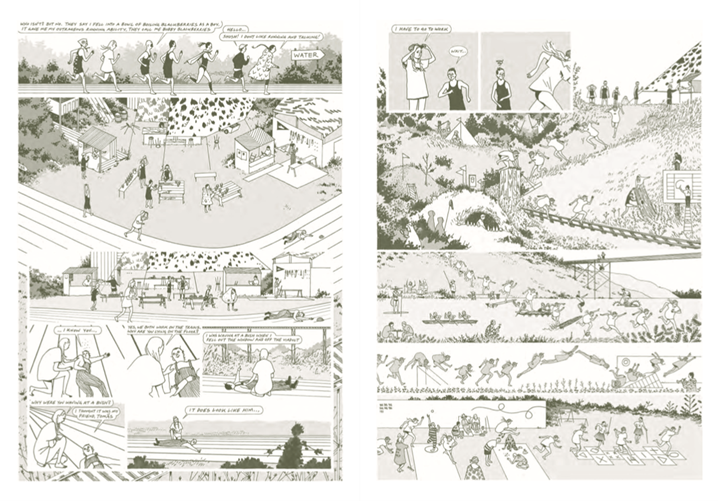

Creation by Sylvia Nickerson (2018)

This is a quintessential Navigating Space Comic. I know little about Michel de Certeau, but by reading The Practice of Everyday Life, I am certain that he would have been extremely glad to read Creation as it perfectly actualizes his idea of walking as a speech and, further, a story. And story as spatial practice. The place of the City of Hamilton becomes a space of not only stories but also heterogeneous characters and identities. As I have said in another essay on Creation, “comics are analogous to cities. …Space is constructed by people’s stories within it and is different for different people. In a city, the poor and rich, the old and young, the abled and disabled, the displaced and gentrifier, the natural and artificial, the high and low, birth and death, love and hate, creation and destruction, hope and despair, methadone clinics and art galleries, are juxtaposed as images in comics”.

(By the way, I should have this work on the Best Comics of the Decade list. Indeed, I saved it for my Best Canadian Comics of the Decade list.)

Fluorescent Mud studies diverse levels of dissociation concerning the phenomenology of the embodiment. For example, dissociation of the body (disembodiment), of the self (depersonalization), with the world at large (derealization), disidentification, with characters, and of the entire narrative, etc. The dis/embodied protagonist explores a disjointed, abandoned space filled with demolished buildings, construction materials, and exposed soils existing on disjointed time.

de Certeau illustrates how Fluorescent Mud can depict different levels of dissociations “Stories about places are makeshift things. They are composed with the world’s debris… These heterogeneous and even contrary elements fill the homogeneous form of the story. Things extra and other (details and excesses coming from elsewhere) insert themselves into the accepted framework, the imposed order… The surface of this order is everywhere punched and torn open by ellipses, drifts, and leaks of meaning…”

(This is another work that I saved it for my Best Canadian Comics of the Decade list.)

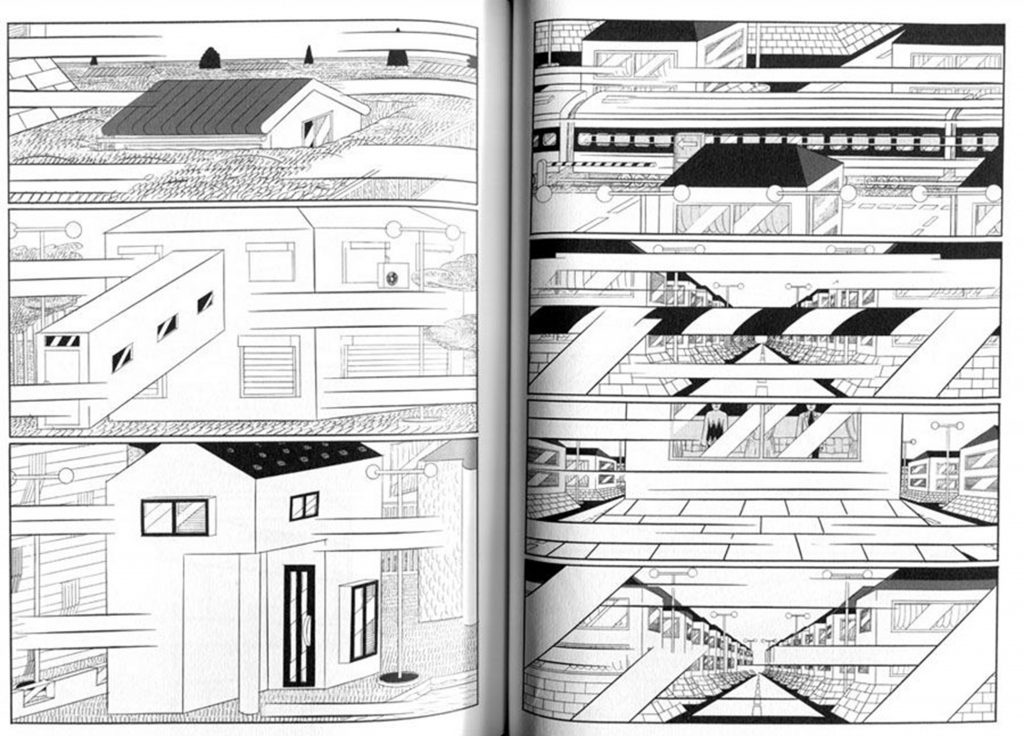

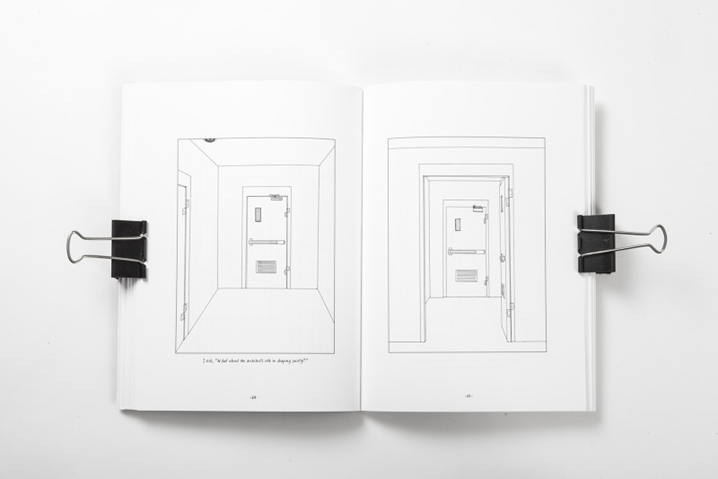

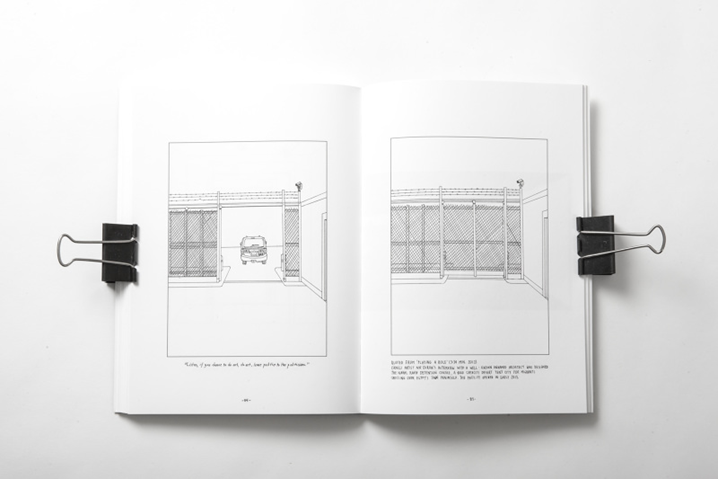

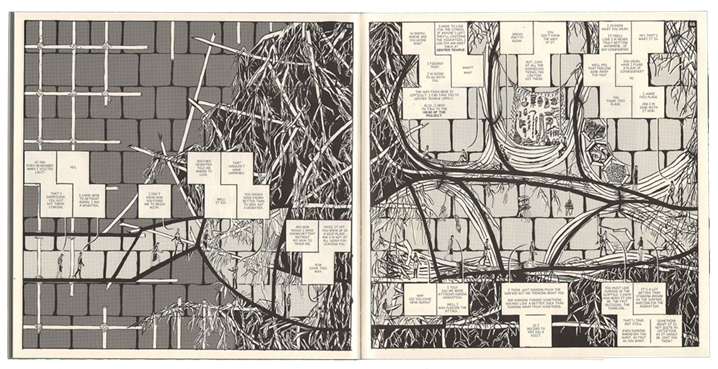

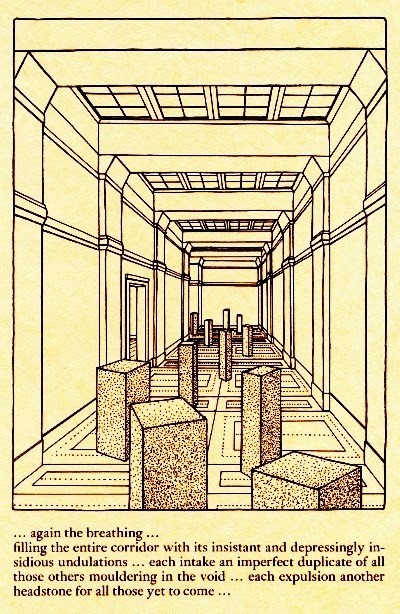

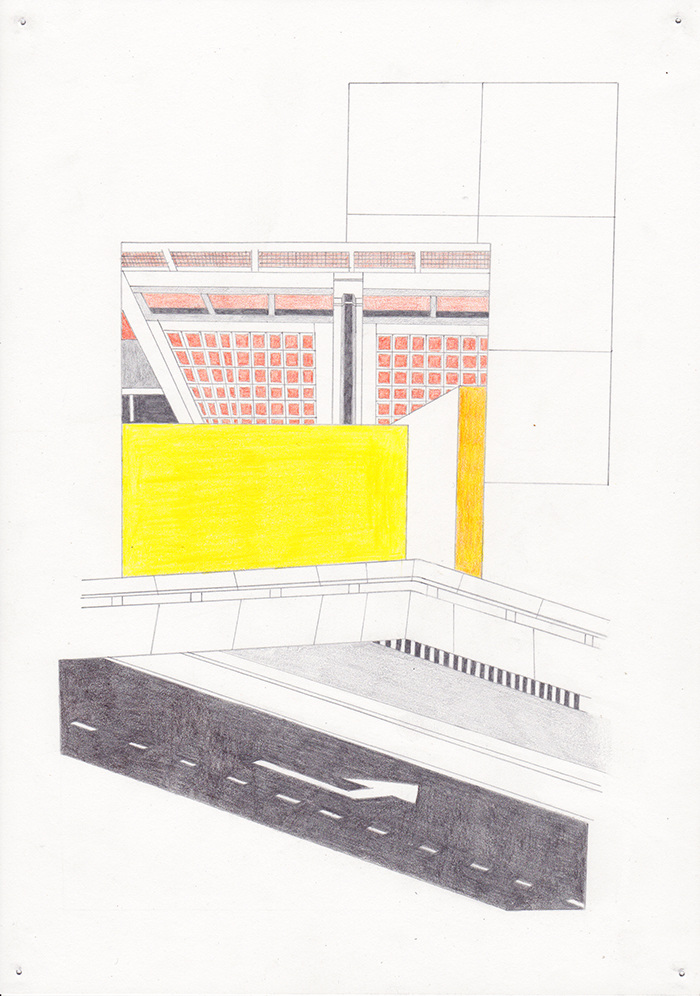

Undocumented: The Architecture of Migrant Detention, Tings Chak (2014)

From the official description:

“Since 2006, over 100,000 people have been jailed in Canada, without charge or trial, with no end in sight. This includes children, who are detained or are separated indefinitely from their caregivers. This is the reality of immigration detention in Canada – a reality that is violently invisibilized. Migrants are detained primarily because they are undocumented. Likewise, these sites of detention bare little trace —drawings and photos are classified; access is extremely limited. The detention centres, too, are undocumented.

Undocumented: The Architecture of Migrant Detention documents the banality and violence of the architecture in contrast to the stories of daily resistance among immigration detainees. This book explores migrant detention centres in Canada, the fastest-growing incarceration sector in North America’s prison industrial complex, and questions the role of architectural design in the control and management of migrant bodies in such spaces. Using the conventional architectural tools of representation, we situate, spatialize, and confront the silenced voices of those who are detained and the anonymous individuals who design spaces of confinement. “

As you read this extraordinary work, as you turn each page, the detention center is spatialized and contextualized in a variety of ways that you can feel what it is like to walk across and stay in the detention center. You will sense how suffocating and inhumane the detention center is.

(This is another work that I saved it for my Best Canadian Comics of the Decade list.)

From my Best Comics of the Decade essay:

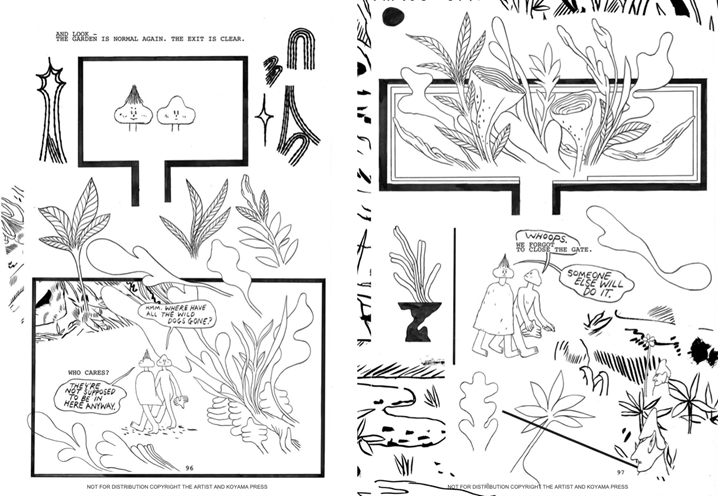

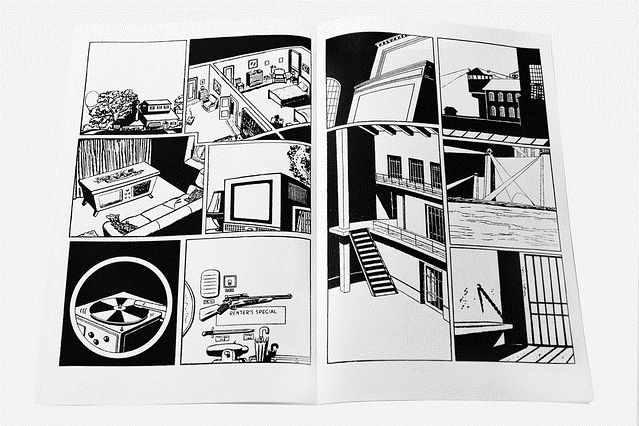

“Patrick Kyle’s oeuvre is a paragon of Navigating Space Comics. Kyle’s narratives are dictated not by characters, like other narrative arts, but by space. Things and space are inseparable, creating a space-medium (Prostranstvennaya Sreda). Manovich contrasted such a continuous world (literal) view with discrete “aggregated” video game space, criticizing the latter as something that needs to evolve and develop as a unified aesthetic. Kyle’s space and objects are distinctly aggregated (of collage); nevertheless, they achieved space-medium, answering Manovich’s call.”

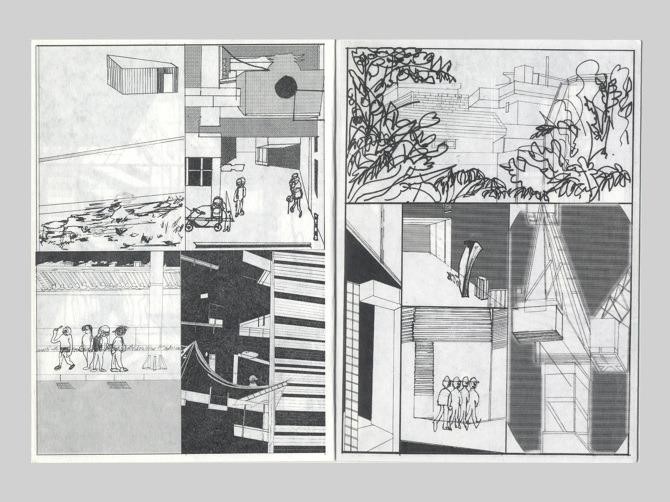

A new entry to Navigating Space Comics, Eight-lane Runaway is basically about eight kids running, but just like any good Navigating Space Comics, a “plot summary” does not do justice. Eight-lane Runaway proves that Navigating Space Comics can be incredibly fun.

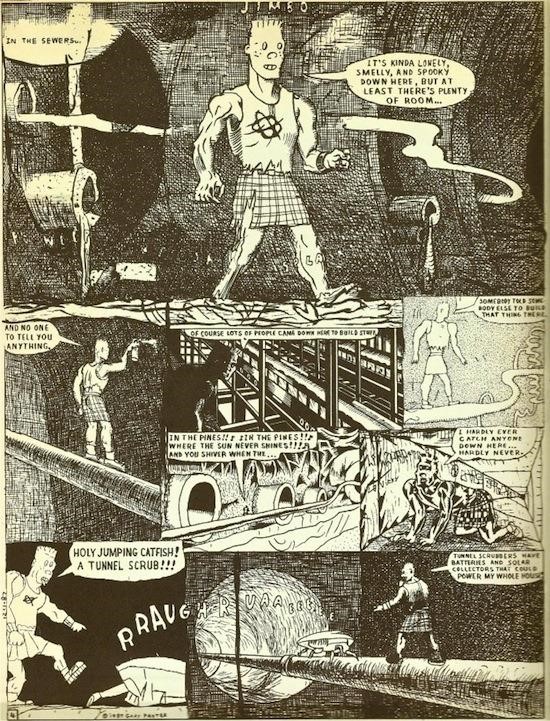

One of the most famous pages from the original Jimbo book. Each panel’s drawing style, especially its background, is different as Jimbo navigates around.

City Strip collages/appropriates superhero comics’ architectures/background/environment/buildings.

City Strips Issue #4 October 2014 Gotham is comprised exclusively of panels from the Batman series set in Gotham City USA, published by DC Comics. Gotham contains at least one panel from each year of Batman between Issue #1 (Spring 1940) and Issue #100(June 1956). Depicted points of interest include Ajax Gas, Gotham Sugar Company, Gotham Map Company, Gotham Docks, and the world-building. Also featured are Wayne Manor, the Bat Cave, the Atlas Statue, the Statue of Justice, and a scale model of Gotham. The front cover image is from Issue #76 (April 1953 ‘The Danger Club’). The back cover panels are from Issue #47 (June 1948 ‘Fashions in Crime!’) and Issue #69 (February 1952 ‘The Batman Expose!’), they feature Batman’s ‘Utility Belt’ and the tombstone of Thomas and Martha Wayne.

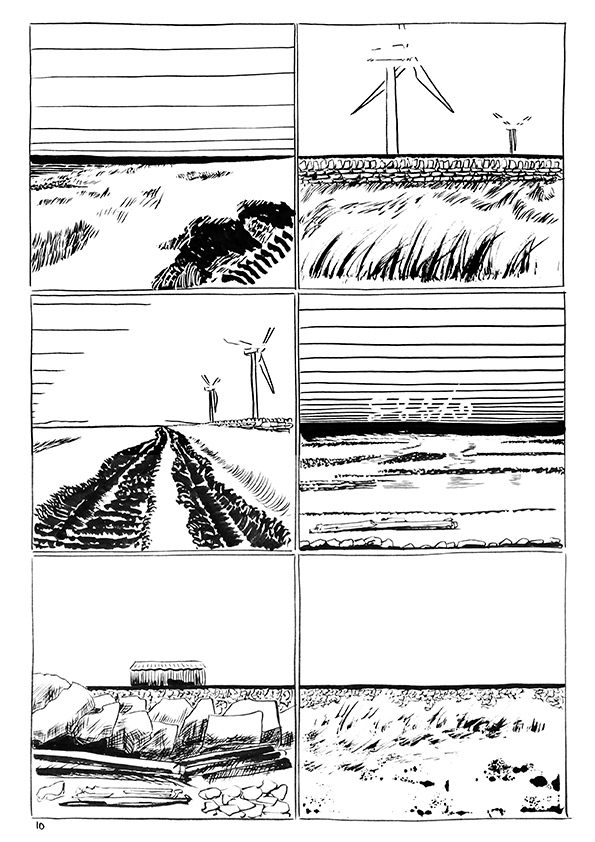

Tim Bird’s oeuvre deals with the psychogeography of the local space around him. The Great North Wood is one of the best comics about geography.

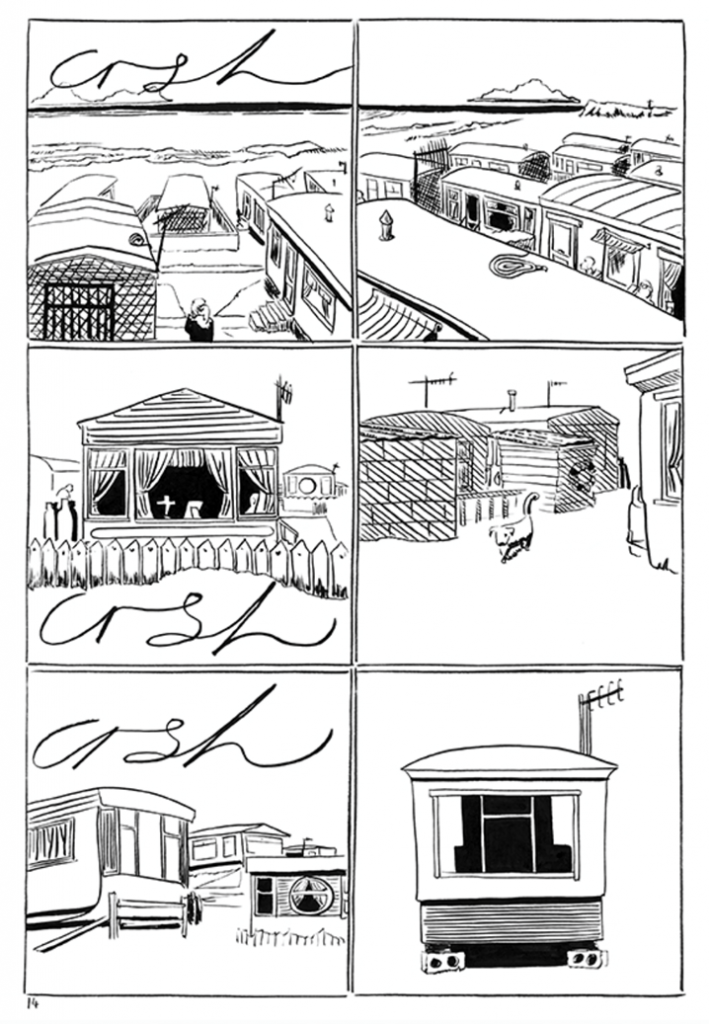

Another quintessential artist of Navigating Space Comics, Oliver East’s entire “Walking Comics” oeuvre is a must for anyone interested in geography and comics.

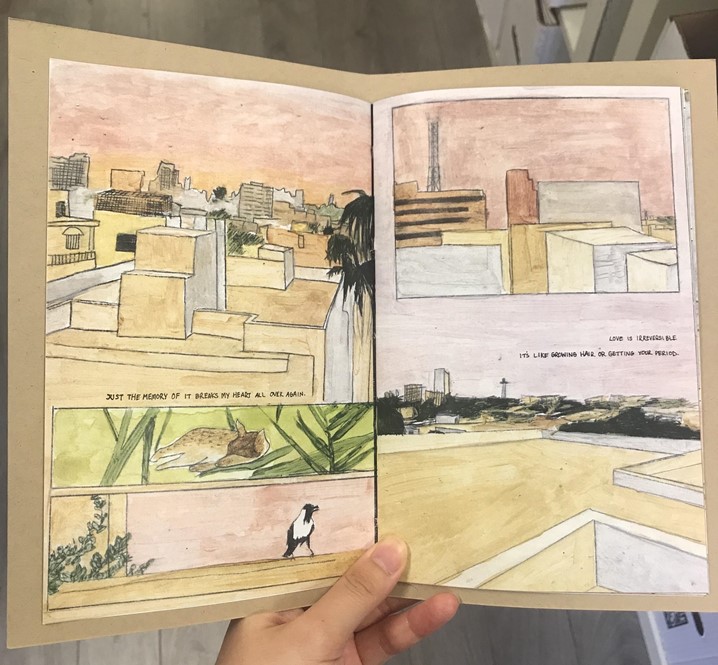

Five Minutes in Karachi depicts Karachi, Pakistan (it’s published in Toronto, Canada, so you can purchase it from the link with a few bucks of shipping fee if you are in North America).

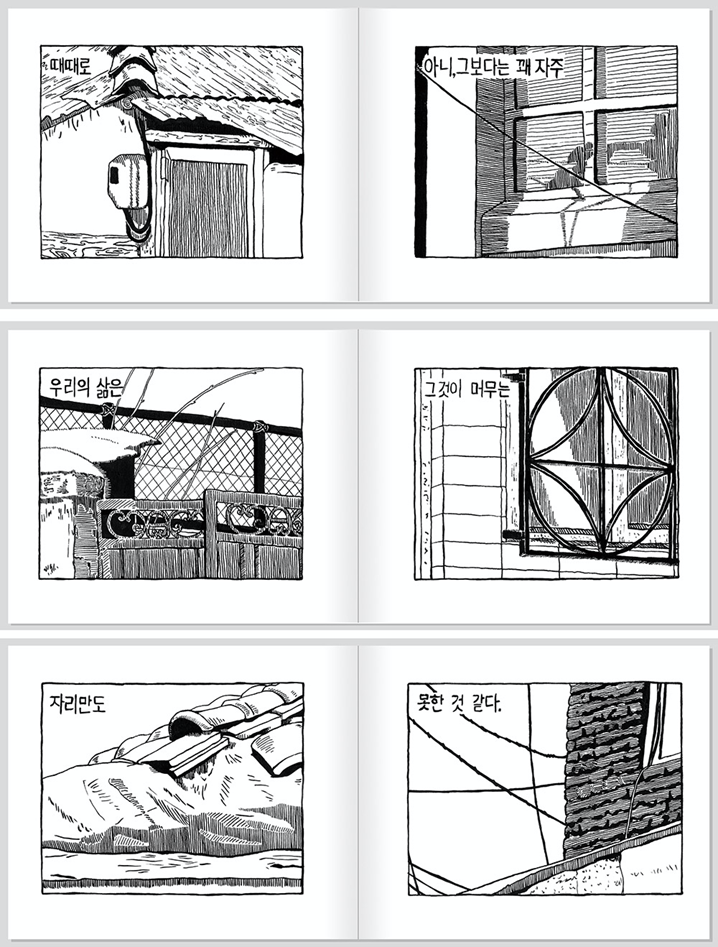

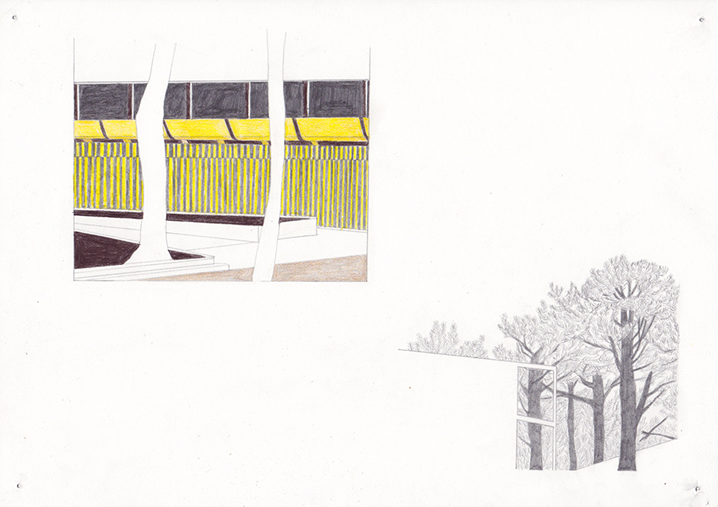

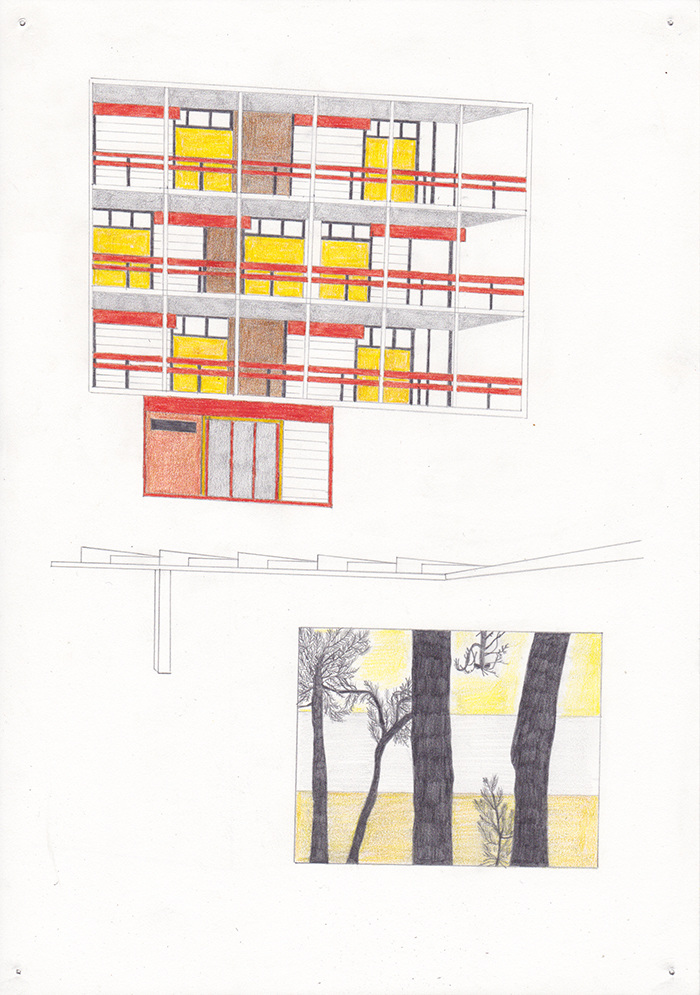

Kim Hyunmin’s oeuvre covers captivating dialects of Navigating Space and Deskilled Comics.

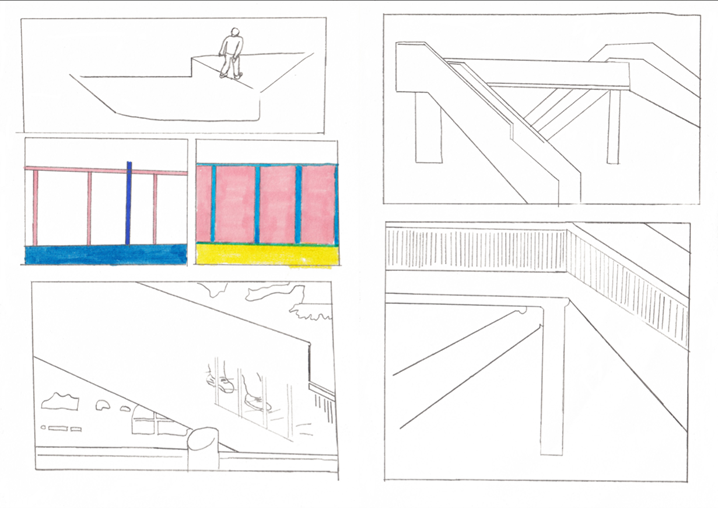

Graham builds worlds and is interested in representing them diagrammatically. Graham’s built world includes games. In Scaffold, the reader sees various scaffoldings of the structure as the character(s) navigate the space.

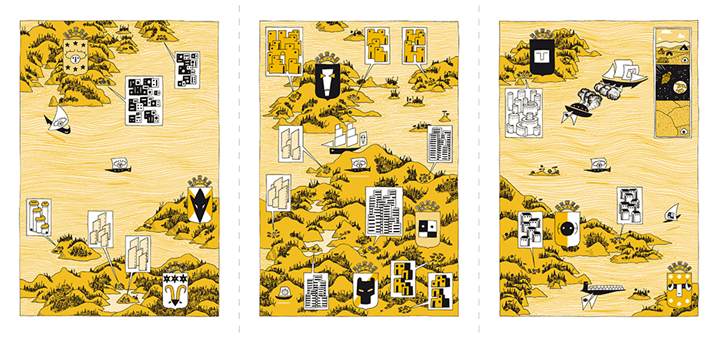

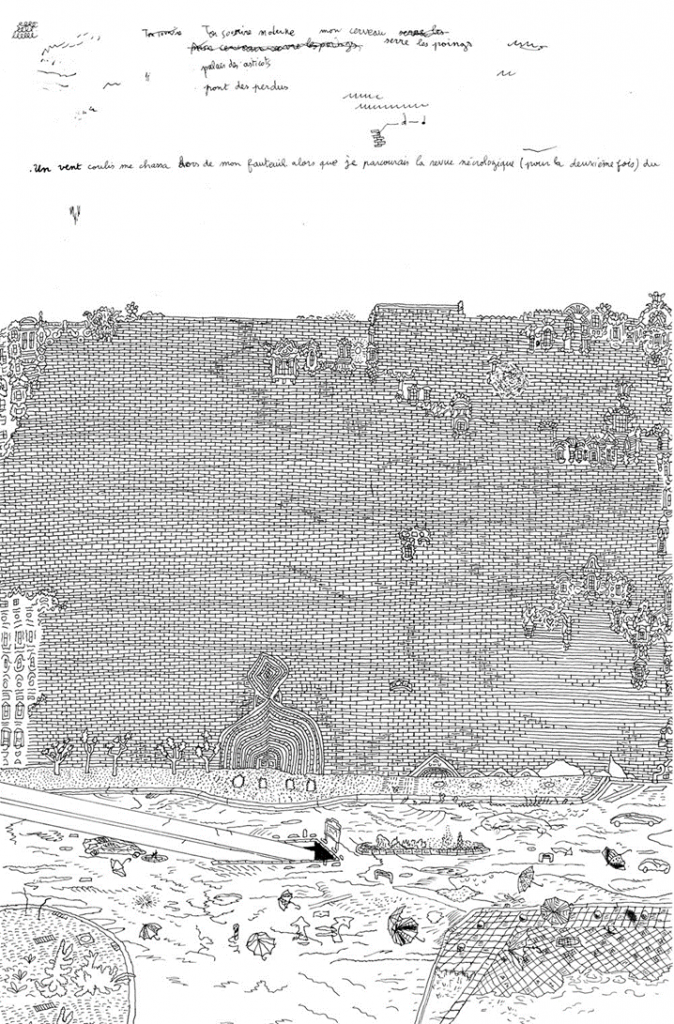

Although not known in the Anglophone world, Alex Chauvel is another exemplary artist in Navigating Space Comics. Chauvel’s chief interest is a representation of space and place on the physical page of comics. Toutes les mers part temps calme, one of the Best Comics of the Decade (that I forgot to include), is a wordless, small leporello, but contains the Big History of everything. It examines the history and evolution of signs (map, diagram, comics, pictograms, language); semiotics, the study of them; humankind; the role of signs in the history of humankind. It is wordless, so do not worry if you do not read French. Just grab it!

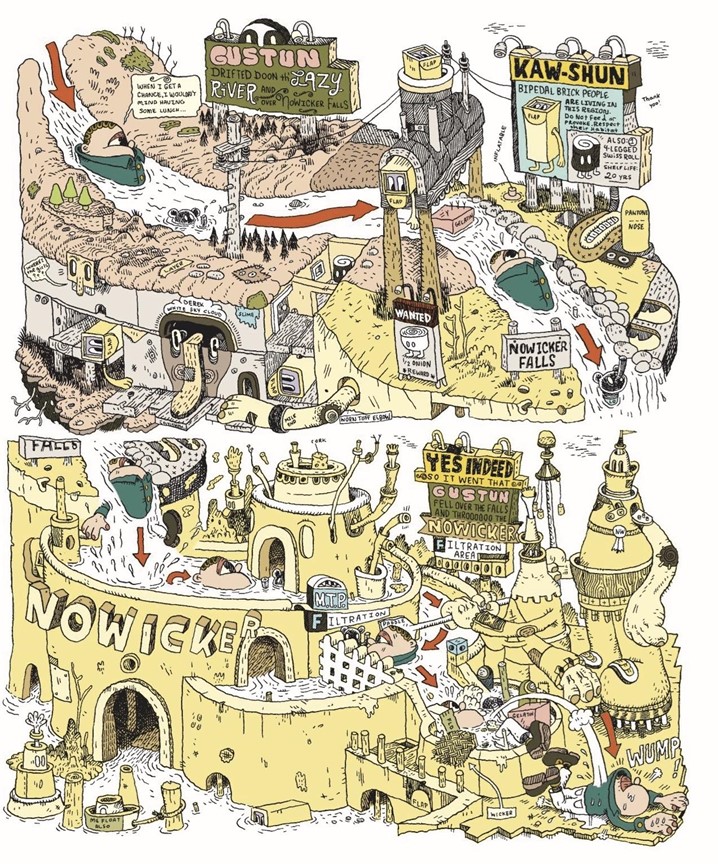

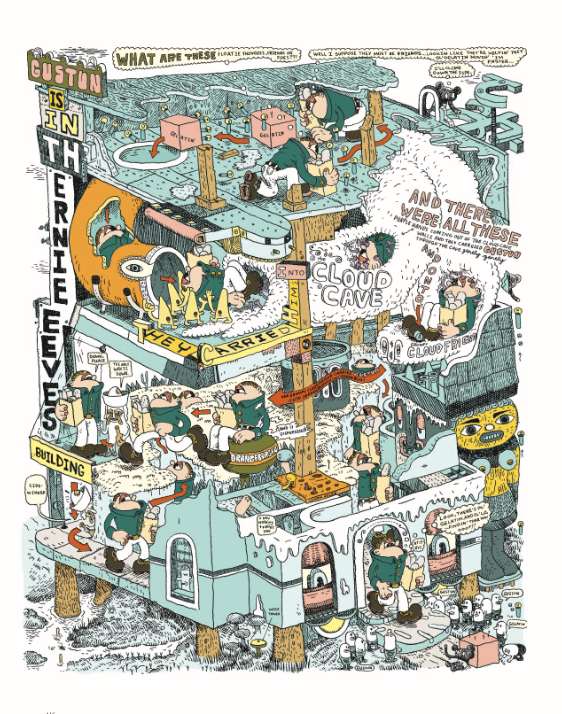

Grutun (“loosely based on characters created by the real Guston”) is one of my favorite comics ever, but I still do not know what it is about. I love it because it is the epitome of Marc Bell’s signature intricate structures and world-building with lots of Canadian jokes spread over. It’s basically Grutun navigating the most Marc Bell of spaces, thus making it the most “Marc Bell” of Marc Bell’s comics.

The first Great Canadian Graphic Novel is about navigating a barren space and witnessing its transformations.

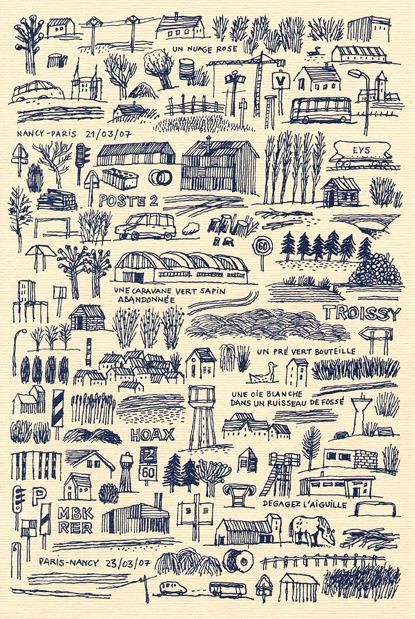

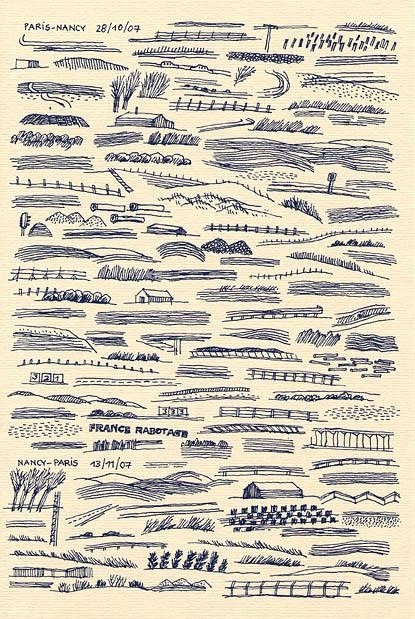

Drawings Jochen Gerner made while on a high speed train between Nancy and Paris.

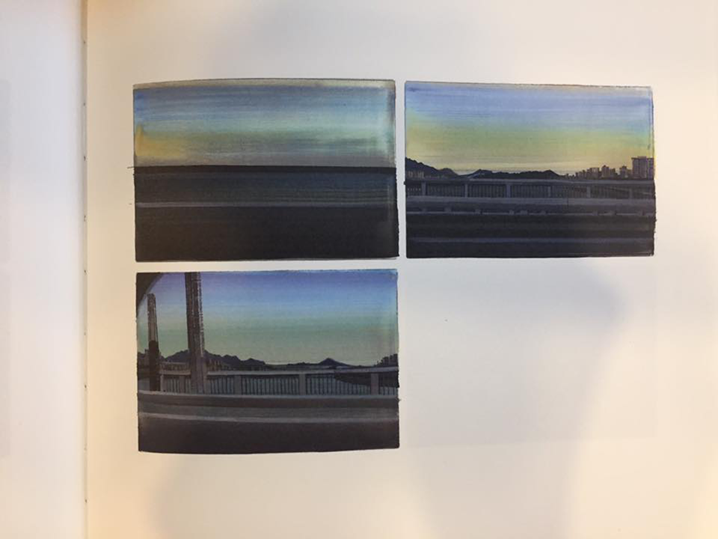

This collection of sequential images depicts days in Seoul; .

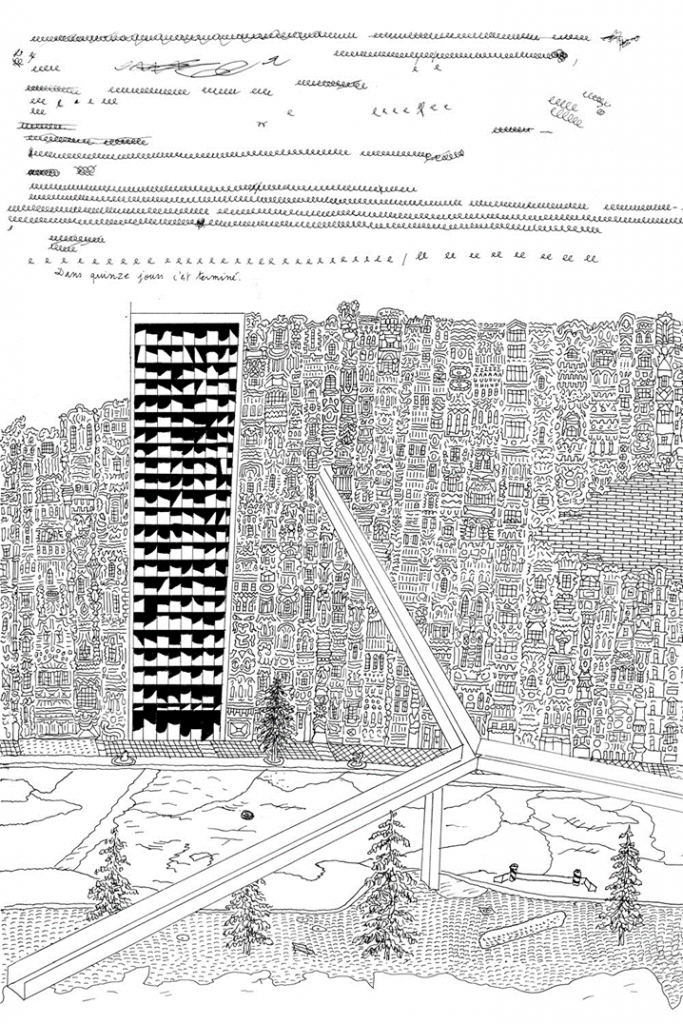

En attendant t’avenue depicts a looong building with an excess of excess. In it, space actualizes as the reader turns each page.

Spatial Poetry

As you have seen so far, a lot of these Navigating Space Comics are poetic (there has been a good deal of debates on the meaning of “poetic” in comics, and I don’t intend to argue a specific meaning here). I contend that this is a specific feature of Navigating Space Comics (rather than because these artists are interested in so-called “art comics”).

At the beginning of this essay, I mentioned de Certeau’s analogy of walking and rhetorical devices, Synecdoche and Asyndeton. I also noted how similar de Certeau’s explanation and comics are.

I presume that the more ellipses/fragments/gaps and analogies/citations there are in the work, the more poetic it feels. Both devices leave room for more interpretations. The reader needs to fill in the “gap” to grasp the work. In contrast, you do not need such laboring to follow step-by-step, explanatory, and prosaic panel sequences. As these devices are characteristics of Navigating Space Comics, we can recognize why Navigating Space Comics feel more poetic.

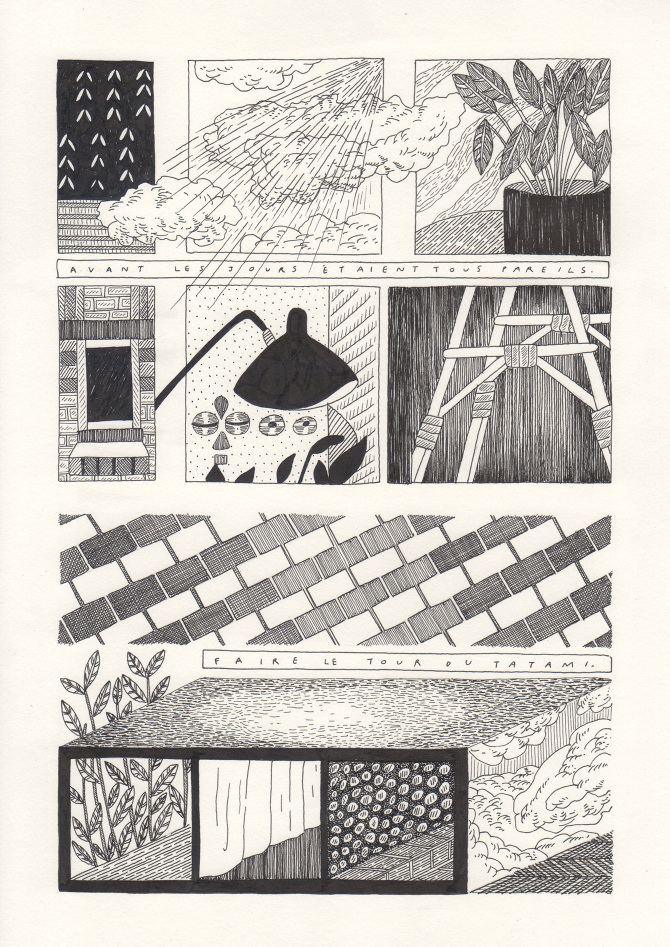

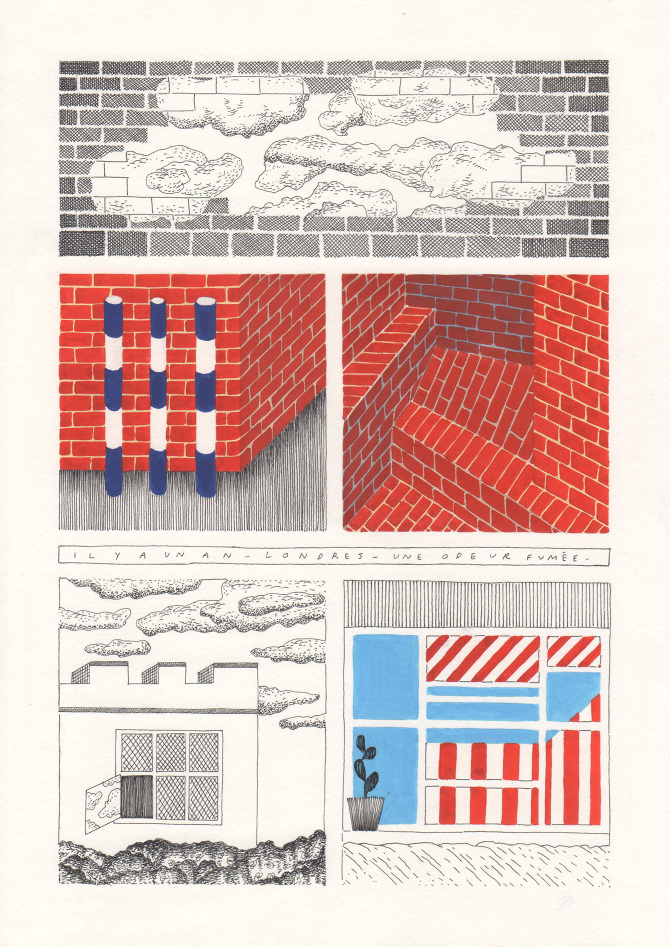

The following Navigating Space Comics are more poetic ones. You can infer how their ellipses, fragments, gaps, analogies, and citations make them poetic. They are also some of my favorite comics ever.

Why Navigating Space Comics?

I included the concept Navigating Space Comics in my Best Comics of the Decade essay because, as you have seen so far, the genre has blossomed in the last decade. There are several reasons. First is the immense influence of “PictureBox artists” to contemporary “art comics.” Besides the aforementioned Gary Panter and Yuichi Yokoyama, the oeuvre of Paper Rad, Fort Thunder, and CF all display aspects of Navigating Space Comics. Especially critical and obvious is the influence of video games on these comics and their creators. But the influence of video games is much broader than a tiny subculture of art comics. We cannot talk about contemporary visual culture, especially digital, without video games (for a detailed discussion of this, please refer to my essay on Deskilled Comics & Meme as Comics).

A second reason that the genre has blossomed is the wider distribution and readership of art comics (or comics with a smaller audience but with like-minded people) thanks to the technical developments of social media and risography (for the latter, a technical re-discovery).

Finally, as I said in the beginning, the new media is a navigable space. We — both the creators and the audience — had already been familiar with navigable space through video games and computers. However, with the growth of the smartphone, now our minds (not our actual bodies) explore the navigable space 24/7. To sum it up, the growth of the Navigating Space Comics genre is thanks to the evolution of new media: from the computer and the video game to the smartphone and social media. And we have grown with them.

It might seem quite paradoxical that one of the most technology-influenced genres, Navigating Space Comics, is poetic. These works compel the reader to take time to ponder meaning, and are proponents of walking, going out, looking around us, instead of staring into what we hold in our hands. But then, it might be because of this exact reason that Navigating Space Comics feel so far away from the small screen of our phones. We create these comics and read these comics to get away from the suffocating but inescapable smartphone landscape that we participate in.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply