Somewhere betwixt Crimson Peak and The Bloody Chamber lies horror maestro Emily Carroll’s 2019 full-length comic When I Arrived at the Castle, an erotically charged gothic tale that evokes and pays homage to horror and fairytale conventions even as it subverts them. On a dark, rainy night, a visitor arrives on the doorstep of a foreboding castle. Mysteriously, this catlike young woman is already expected by the estate’s threateningly enigmatic, yet seductive Countess.

Central to Carroll’s horror ethos is the seemingly facile trope that nothing is as it seems, but Carroll takes this a step further with her comics, which frequently border on cosmic horror with the implicit thesis that nothing is fully knowable. Often in Carroll’s comics the “unknowable” figure initially masquerades as a person, but is revealed to be…not. Her preoccupation with the unreliability of human façade and veneer is as clear in When I Arrived at the Castle as in her shorter comics like “His Face All Red” and “Some Other Animal’s Meat”. Or, to put it another way, Carroll is very interested in skin and the shedding thereof, but who – or what – lies beneath it challenges the reader’s expectations of any essential truth. Or – possibly more unnerving – perhaps under the surface there’s not anything more than blood, bone, and viscera.

This concept also challenges the role of the archetypes which Carroll utilizes, namely whether or not they can be pinned down as narrative shorthand for anything, however much it’s the reader’s inclination to do so. We think we’ve met these characters before, we believe that we’ve heard this story – up until a point. Carroll complicates the patriarchal and predatory associations of vampire fiction with a story about two women, as bent on ravaging as ravishment. When I Arrived at the Castle begs the question: who is hunting whom and to what purpose? Her protagonist arrives with the intention of destroying the ostensibly destructive countess, lifting the pall of danger that hangs over the surrounding forest due to her malevolent presence. But as the book progresses, the straight line of this familiar story becomes increasingly tangled and fraught.

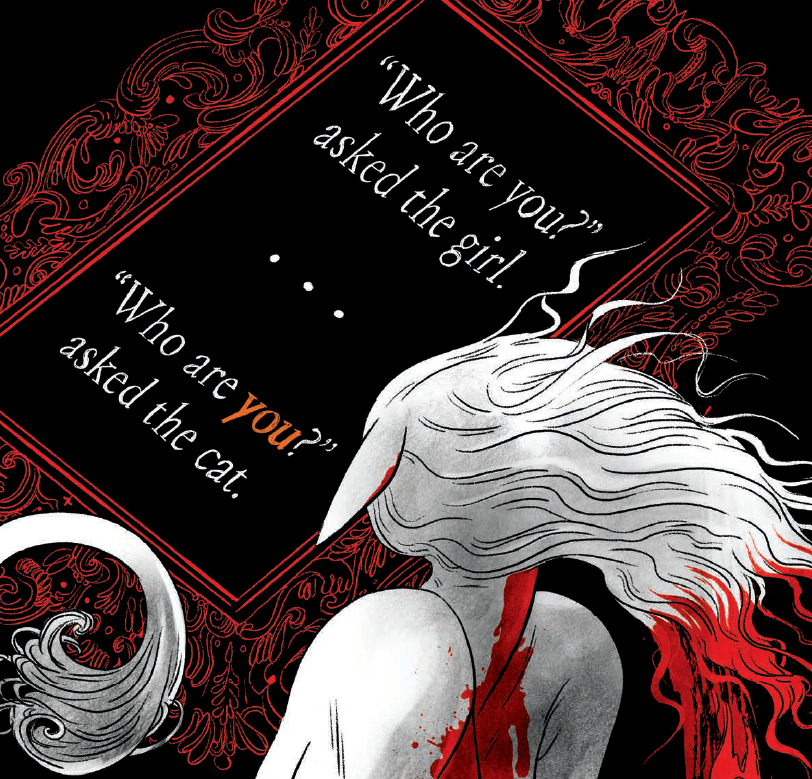

Who is the countess? Our cat woman espies her, in one of the book’s most beautiful and visceral jump scares, sloughing off the skin of a woman and revealing a sticky red nightmare underneath. Carroll’s sumptuous illustration and masterfully effective page composition is in full force here – I’ve never been as startled by the turning of a page. Everything from the framing (a keyhole, implicating us in the protagonist’s voyeurism), to the contrasts of the book’s bloody scarlets against a black and white backdrop, to the evocation of swift, dangerous movement, cements Carroll’s place as one of the most skilled horror cartoonists working today. Similarly, her lettering of onomatopoeia, like the banging on a door, is practically audible – Carroll employs every tool available to her to create a powerful sensory experience.

Even as it is revealed to the reader that neither of these characters are quite as human as they appear, the implication is that they are, perhaps, both most human and most other when we see them revealed as hungry and bestial creatures, voracious for flesh to consume in both senses of the phrase, drawn to one another even as they are repelled.

Carroll’s visuals are incomparable: her writing is an intriguing counterpoint to them, rife with so many similes it might be funny if the tone wasn’t so perfectly balanced. The Countess catches our cat woman peering through the door and spirits her forcefully deeper into the castle, “down hall after hall” to a room full of “Doors, like a nest of ravenous baby birds their mouths yawning from floor to ceiling. And I, a worm, dangling in her beak.” When I Arrived at the Castle never strays far from the language of hunger, a hunger that will never be content with anything less than live, struggling prey for its satiation. Behind these doors, where you expect subterranean rooms populated by further chimerical horrors, Carroll instead introduces prose fairytales-within-the-fairytale, recursive mirror archetypes, interchangeable signifiers of unadorned text. As the book progresses, the reader is increasingly unsure whom – or what – is being referred to by words like “girl”, “woman”, “cat”, “animal”, and especially, “monster”. Skin, as well as the appearance it suggests, is little more than a guise, that can as easily contradict essence as represent it.

In Carroll’s prosaic fairytales are stymied maidens met by a devilish cat imparting ostensibly well-meaning advice alongside its trickster’s token. A proffered knife, charged with both violent and erotic possibility, opens reflection upon the specular and illusory castle. The castle’s appearance requires an askance look at the self, a crooked introspection, like the not-quite-reality of a dream.

Of the two central characters, readers are not left with the tools to make a clear judgment to which polarity each belongs: protagonist or antagonist? Woman or animal? Predator or prey? Strong or vulnerable? Just as we are left confused about which side to take, or if there are sides at all, we are also struck by the tension between the cat woman and countess, who seem to simultaneously and counterintuitively intend to both possess and destroy one another. And who, the countess asks, can really be held accountable for the spilling of blood, when both knife and wound seem to so enjoy the ritual?

In the end, what is so satisfying about Carroll’s oeuvre is its resistance to a single reading or interpretation, and When I Arrived at the Castle is no exception. Shedding one skin, discarding one layer, or turning one page, does not mean that you’ve reached the core of anything. Maybe any character only exists, after all, as an accretion of disguises, a built-up mythos to which storytellers may choose to refer or allude, and readers may choose to recognize.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply