There’s an old Hollywood anecdote that, like the best of them, may or may not be true — but sure sounds like it could be.

It goes thusly: on the morning they filmed the famous “dental chair scene” for the classic 1976 thriller Marathon Man, co-stars Dustin Hoffman and Laurence Olivier took vastly different approaches. Hoffman was a method actor to the core and duly stayed up all night, showing up on the set disheveled, tired, not having showered, entirely “in character.” Olivier, for his part, was old school — he took off his overcoat, got into position, and nailed all his lines in one take. Afterward, the exhausted Hoffman asked his counterpart how he managed to do such flawless work with apparently no preparation whatsoever, to which Olivier replied: “My dear boy, have you tried acting?”

Word is that Bradley Cooper, like many of today’s “A-listers,” is another “method” guy, but in the near-future world of Connor Willumsen’s Bradley Of Him (Koyama Press, 2019), Cooper takes Lee Strasberg’s methods to extremes not even Hoffman could have dreamed of with his biopic portrayal of disgraced cyclist-turned-triathlete Lance Armstrong. He’s nominally a guest at The Mirage in Las Vegas (kind of an offbeat choice given that most of the Hollywood glitterati typically stay at either Caesars or The Wynn, but whatever), and even enjoys the buffet and hits the slots (again unusual, given that you’ll usually find celebrities at the high-stakes blackjack and Texas hold ‘em tables), but most of the time he’s simply running. And running. And running.

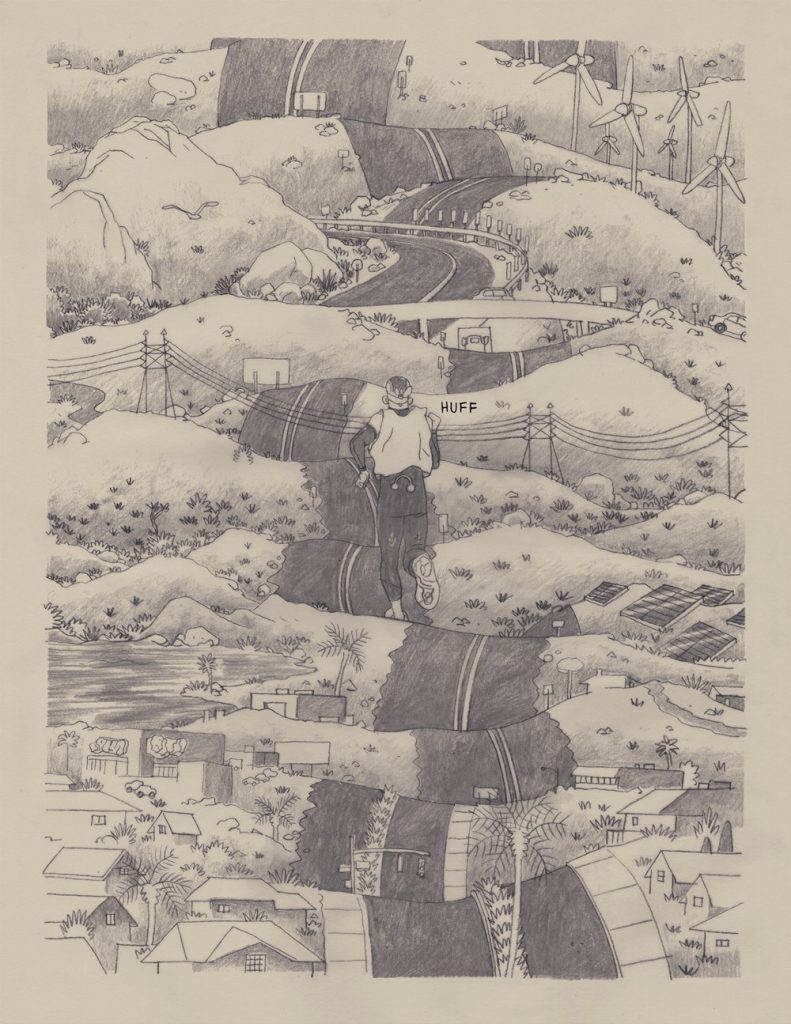

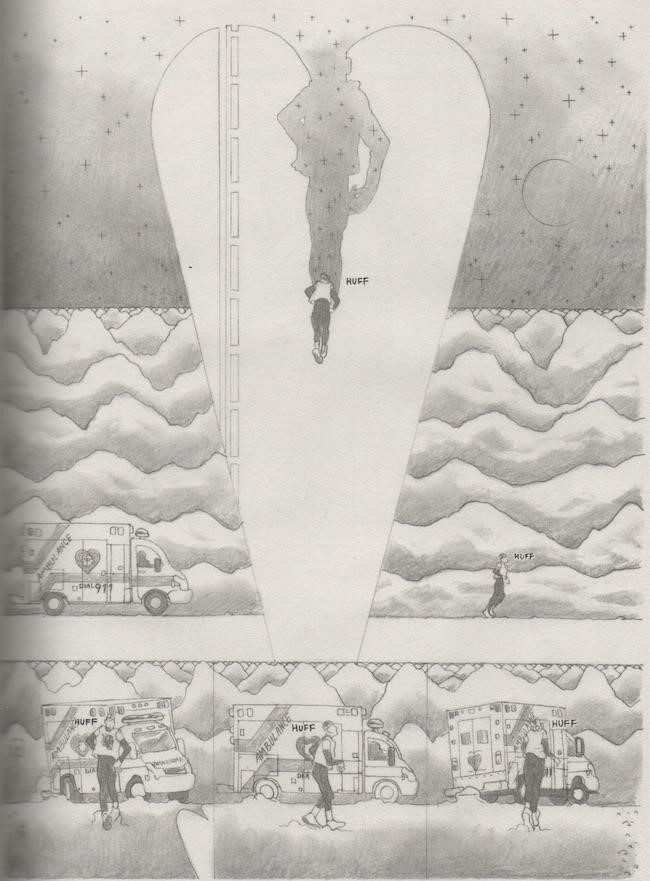

In fact, the act of running is very much Cooper’s equivalent of “never get out of the boat,” to quote another classic Hollywood production. The question, though, is whether or not he’s running away from something or toward it, and, in typical Willumsen fashion, it’s not one that he’s going to answer visually, serving up page after page of circular and elliptical spreads free of panel borders, rich with shading and detail, which the reader can interpret in almost any “order” they choose.

Which isn’t to say that the overall thrust of the narrative can’t be as linear as you wish it to be. It can. But even then, there is no hard-and-fast map that you’re required to follow. The basic events are easy enough to suss out: Bradley Cooper composes a letter to Robert DeNiro in his mind (and on paper), Cooper refuses medical attention while running through the desert, he meets an unusual extended family whose kid puts him “on the spot” in a manner both jovial and challenging, he visits his sister and her kid, he whiles away a little bit of time playing a video slot machine based on the noxious animated series Family Guy, he accepts an Academy Award for best actor — okay, he’s not always running, but his breaks from it are short, and he always gets back to it.

And, like Willumsen’s endlessly-inventive page layouts, time doesn’t run in a straight line here either — Cooper misplaces his Oscar before he wins it; his letter to DeNiro can be read as either a sincere paean to his acting hero written in anticipation of his winning the same award for which Cooper’s been nominated or an “I told you so” after DeNiro loses out to him; and, perhaps most mysteriously, he appears to be living as Armstrong 24/7 even though the film where he portrays him has already been made.

That’s not even the whole of it, though — one can even walk (or run) away from this book fairly convinced that Cooper himself isn’t Cooper (he’s always wearing shades), but is actually his nephew, Murray, who’s “playing” his uncle Brad, who is, in turn, playing Armstrong. If you choose to go that route — a potential viewpoint that would likely necessitate a separate review/reconsideration — then what you’re looking at here is a David Lynch-style narrative dealing with Michael DeForge-style themes of identity and artifice. That being said —

If one chooses the more straightforward (relatively speaking) approach, what we’re looking at here is actually a fairly comical skewering of glitz, glamour, voyeurism, Las Vegas excess, and Hollywood’s nauseating culture of self-congratulation, all told in an imaginative, though by no means indecipherable, “roundabout” chronological order — an old Tarantino trick, to keep the cinematic comparisons going. That’s a fair reading, perhaps even the one most will adhere to, and arguably even the one Willumsen himself was attempting to put across, but it’s not the only one possible, and that’s what makes this such a conceptually exciting work.

As anyone who’s read Willumsen’s previous book, Anti-Gone, can tell you, this Montrealer is a cartoonist who seems to function at one speed, and one speed only: overdrive. Indeed, as dense and multi-layered as his pages are, each one almost seems to struggle against the sheer volume of visual information they’re attempting to convey — and that’s by no means meant as a criticism. One way or another, Willumsen always finds a way to translate his extraordinary imagination into imagery that not only catches, but fully absorbs, the attention of the reader, and that’s no mean feat considering the sheer size, scale, and scope of his ambition. Like his protagonist, he’s forever pushing himself — he never stops running.

And while running to your comic shop to pick this up isn’t a possibility for most of us right now given “shelter in place,” Bradley Of Him is a book that you’ll want to obtain immediately, and one that will probably be much-discussed come our own end-of-year “awards season” in comics as many of us will be in the midst of our fifth or sixth re-read of it at that point, and picking up something new from it each time.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply