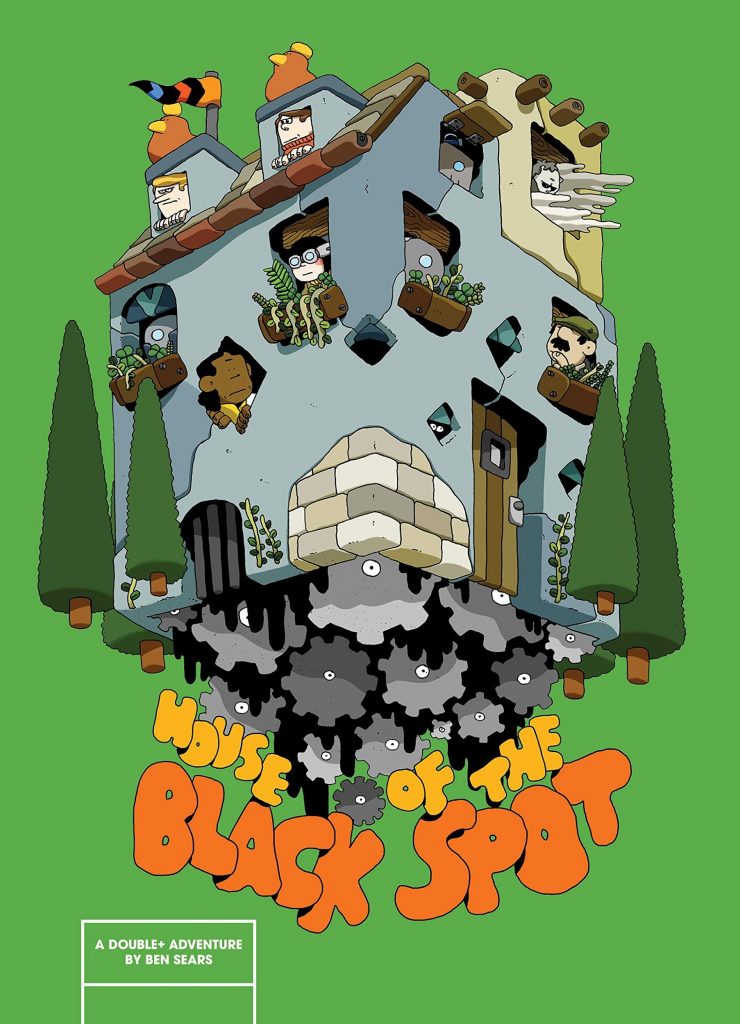

Timely, topical, and utterly engaging in the most unforced manner possible, cartoonist Ben Sears’ “Double+” series of all-ages graphic novels from Koyama Press is one of those rare projects — and by that, I mean rare in any medium, not just comics — that gets stronger and stronger with each subsequent entry into its hermetically-sealed “canon.” Colorful, inventive, and kinetic in every sense of the term, Sears’ increasing confidence as a visual storyteller is clearly discernible from one book to the next, and his latest, 2019’s House Of The Black Spot, continues this happy and welcome trend.

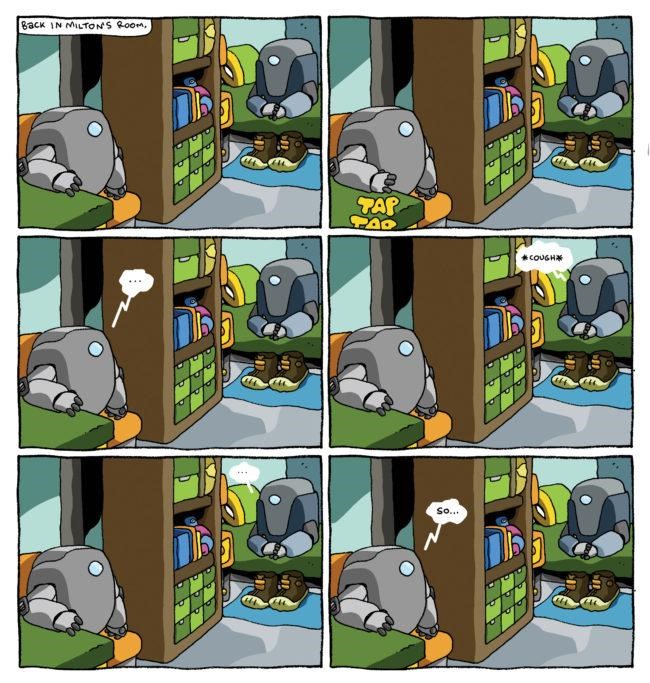

And those two words — “happy” and “welcome” — are easily-applicable to each new roughly-annually-issued Sears book in a general sense: when the latest installment of the adventures of “light comic” hero Plus Man and his mechanical sidekick/best buddy Hank arrives in the mail (or at your bookshop), it feels like a chance to catch up with old friends who never let you down and to see what they’re doing, how they’ve been doing, and marvel at whatever misadventure they find themselves in next. Both characters are eminently likable and good-natured, and, while they live in a fantasy world entirely more interesting than our own, Sears utilizes them as a means of exploring issues with which we’re all too familiar.

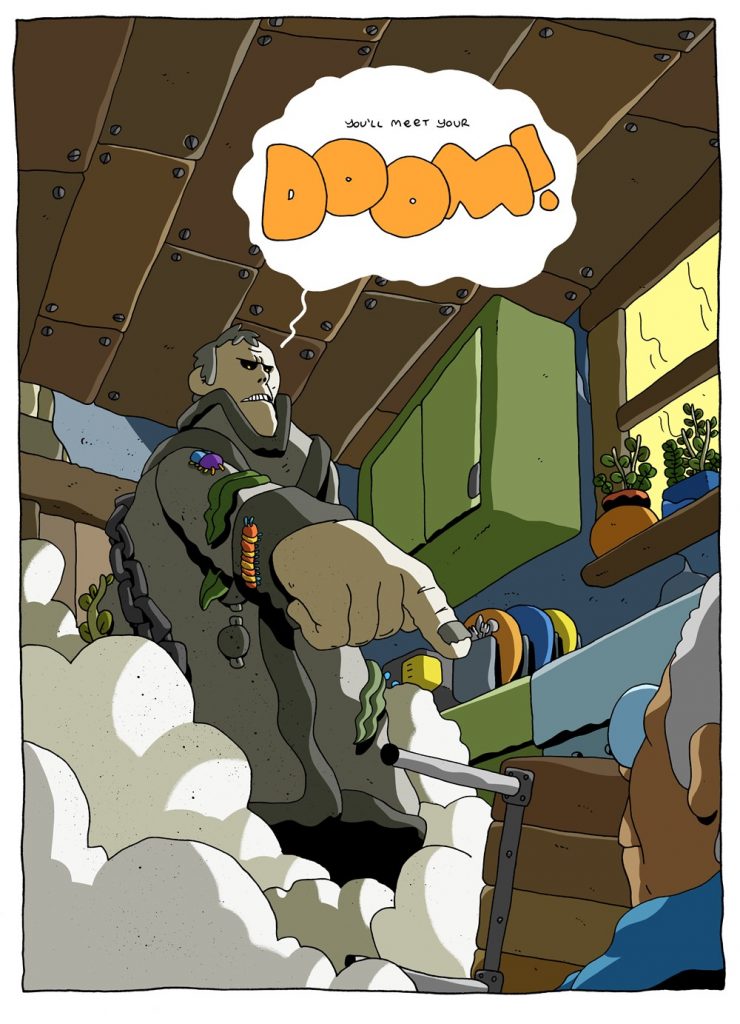

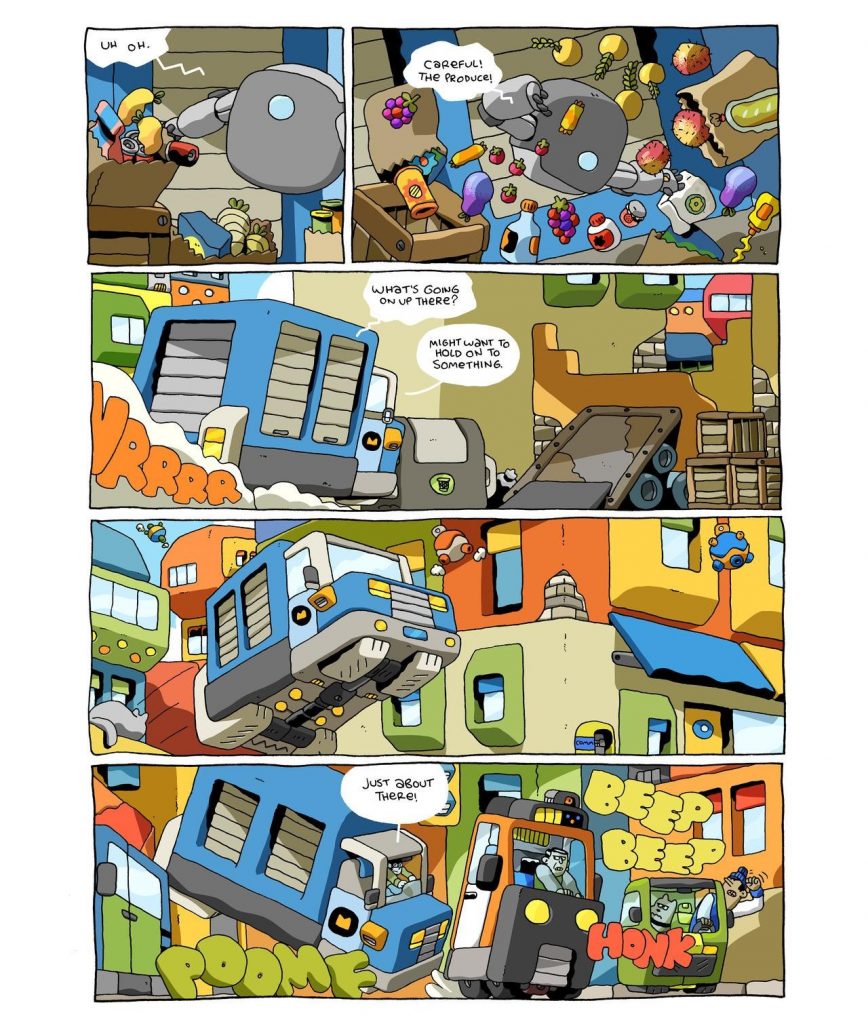

Gentrification and urban redevelopment/displacement are the focus of his narrative in House of the Black Spot, as our heroes travel to Hank’s hometown of Gear Town for the funeral of his Uncle Bill (if you can’t get past the notion of machines having families, and that those family members are just as capable of dying as any flesh-and-blood creature, then you’re reading the wrong series), only to be swallowed up into the jaws of a vast conspiracy when it turns out that Ben was, in fact, murdered. It’s not just any old greedy real estate magnate who is at the center of these intrigues, though, but the ghostly phantom of a dead real estate magnate!

As with all fantasy-based narratives, particularly those aimed at what’s loosely termed a “general audience” readership, suspension of disbelief is a necessity going in here, but Sears has no trouble selling audiences on the spectacle and the supernatural, so clearly unified is his artistic vision. He draws sprawling vistas loaded with imaginative details that are sure to transfix any kids reading his books, but he imbues them all with enough conceptual familiarity to keep adults engaged — and his uniformly clever page layouts, character designs, and panel-to-panel storytelling fluidity are enough to impress even those most veteran aficionados of the comics medium. Hell, he might even win back hopelessly jaded folks who are convinced they’ve seen it all.

Sears’ illustrations are a deceptively-simple marvel to behold, clean lines layered with a generous helping of eye-popping color and expertly-placed digital shading effects, creating a visual world that is fresh and new, even alien, but in no way unfamiliar. His locales are fantastic, but look and feel lived in, and this goes no small way toward “selling” audiences on the social, cultural, and economic pseudo-realities that he structures his story around. In short, you buy into the world he creates because he buys into it himself, and has thought through every aspect of it in such detail that he’s able to communicate it all with a kind of matter-of-fact nonchalance that can’t help but resonate with his readership. There is danger here, and mystery, and a good deal more complexity than many “all-ages” cartoonists dare to incorporate into their works (no offense intended toward any of them), but it’s all delivered in a gentle, borderline-playful manner that puts readers at ease with the notion going in that, yes, by story’s end, everything’s probably going to be alright — but that doesn’t mean we won’t be glued to the page as to see how that tidy resolution is going to come about. In that regard, then, Sears borrows more of his overall tone — as well as his penchant for exceedingly clever dialogue — from newspaper strips of yore than from comic books, per se, but his structure and pacing are all thoroughly in line with modern “graphic novel” sensibilities. It’s a pretty wondrous balance he’s achieved, really, when you stop to think about it — but, as is this case with the best “suitably for all readers” narratives, you don’t feel particularly compelled to stop and think about it (apart from taking in the wondrous artwork) until the book is over.

And while we’re talking of things being over, House Of The Black Spot does, indeed, mark the end of the road for Ben Sears at Koyama Press, publisher/proprietor Annie Koyama having made the thoroughly-reported-upon decision to move on to the hopefully-greener fields of direct artistic patronage. And while the book ends on a note that would serve as a perfectly adequate finale, the door is also clearly left open for more “Double+” adventures in the future. I believe Sears has more to say with the characters and this world, and so while I am, at this point, inclined to follow where he leads — whether that’s back into this “universe” or to parts so-far unknown — it’s my earnest hope that somebody like Fantagraphics, Conundrum, D+Q, or maybe even First Second will realize what a marvelous series he’s created here, and will eagerly offer him the chance to continue it under their auspices. Some places, after all, are just too good to leave behind.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply