When I first saw E.T. as a child, I had nightmares for weeks. The bulbous creature, greedily munching on candy, was overwhelming to an easily startled three-year-old. With its rapidly elongating and contracting neck, and a head too large for its squat body, E.T. seemed like some kind of demon. The fear I had as a child from seeing that creature seems baked into me now, a visceral haunting by a movie that, by all accounts, was a tremendous success in the public sphere. E.T., I’m told, isn’t scary at all – it’s milquetoast.

I have vague memories of the adults in my life trying to convince me that E.T. wasn’t a bad guy. He was cute! He was friendly! He healed people and brought dead plants back to life! I wasn’t convinced. And perhaps this experience became the root of something deeper for me — the realization that other people’s eyes were not my eyes, their fears not my fears. And then, more worryingly, how could people who didn’t see the obvious be trusted?

Imagine my surprise this year when Adam Szym released Little Visitor last October, a 22-page horror comic that deals with the troubled production of a Russian E.T. knockoff film called Little Visitor. Here was a comic that seemed to echo my exact experience with E.T. Here was a comic that awakened something buried deep in me, without me knowing exactly what it was.

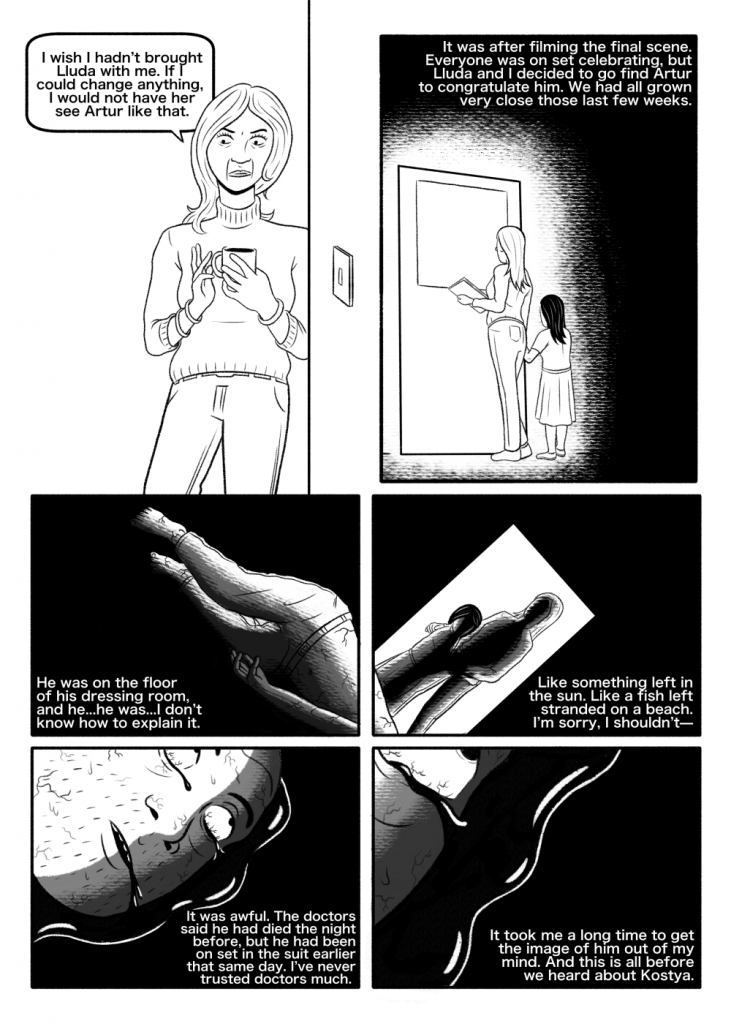

Little Visitor is written to resemble another type of media, investigative journalism à la 60 Minutes. The cast, producers, and directors of Little Visitor all sit for a camera and answer questions. Their monologues play over a selection of memories, scenes, and paraphernalia. Through this, Szym reveals the troubling details of the Little Visitor movie and its horrible end.

Little Visitor focuses on Kostya, a young boy cast in the movie for unknown reasons at the insistence of a government apparatchik. At first, Kostya seems like a natural for the film, but when the design of the alien buddy is introduced by the obsessive artist Anatoly, he goes berserk with fear. This fear waxes and wanes throughout production, but it reaches a head at the end of production. It is then that things get a little complicated.

Littler Visitor is a black and white comic, as is much of Szym’s oeuvre, but it exists at something of a turning point for Szym as an artist. Much of his previous work is effective, but rough around the edges. Comics posted on his website show Szym developing a sense of what works as a horror comic, but the drawing isn’t all there, or the panels don’t flow well. Little Visitor, though, seems to be a remarkable advance from his previous work. The illustration and drawing are stronger, the page layouts more effective, and the storytelling more keenly focused.

The differences between what we see a thing as and what we believe that thing truly is can be a potent source of unease, and Szym explores that idea in Little Visitor. Why is Kostya so frightened by the alien suit? What does he know, or what does he sense that others don’t see? Another cast member, a girl named Lluda who played another part on set, reveals in the latter part of the book that she also experienced the same gut-reaction to the creature, but ignored it because she felt as though she was mistaken. The adults think the costume is cute, so it’s clear that they must be right. In this comic, the fact that children were the ones who saw the truth is telling. Adults, more preoccupied with the fame and wealth that could be garnered from the work they were doing, could not see what Kostya and Lluda saw. We see this theme of obscured sight expressed cleverly in the way Szym’s places his characters in each panel; while all the other characters are seen fully on panel, Kostya’s eyes are always obstructed from view.

Szym seems to be contemplating the nature of greed and sacrifice in this work, as well as how children can suffer from the decisions of adults who are trying to turn a profit. In Little Visitor, Kostya is offered up as something of a sacrifice to the god of money, and he’s not the only one. Anatoly seems to be working for something outside of his own control, or perhaps in an attempt to gain something worth more than mere dollars. What he actually gets is far more gruesome.

To a certain extent, this major theme of greed is another linkage to E.T., where the fate of the little creature and the humans it has bonded with are of no concern to the government agents attempting to secure it for their own research. These children suffer under the hands of adults, but, through the power of friendship, they are able to overcome those malevolent forces. The characters in Little Visitor are not so fortunate.

Szym also uses the 60 Minutes nature of the comic to get at a final point; that humans have a tendency to block out the horrible things that they see. What happens to the actors in Little Visitor is a mystery to the director and producer of the movie, or so they claim. No one knows what occurred, and no one is that interested in finding out. Do we accept the possibility that things are more twisted or awful than they seem? Or do we hide in our understanding of the world, in our bubble? And if so, what are the costs?

I think Little Visitor is a remarkably complete and effective horror comic, but what fascinates me most about Little Visitor is how it cleanly tracks with my own lived experience. I thought my fear of E.T. was an anomaly, that this aversion was individual and unusual. I’ve never heard anyone say that they were scared by E.T. (although to be fair, it’s not a question I ask folks at parties). This, more than anything, is what startles me about Little Visitor. It seems purpose-made to examine the very terror that wracked my childhood dreams all those years ago. But Little Visitor isn’t just a personal experience; it is also a powerful rumination on the forces that drive modern society and their effect on those without power.

Alex Hoffman is a comics critic and the Publisher of SOLRAD. Find more of his writing here.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply