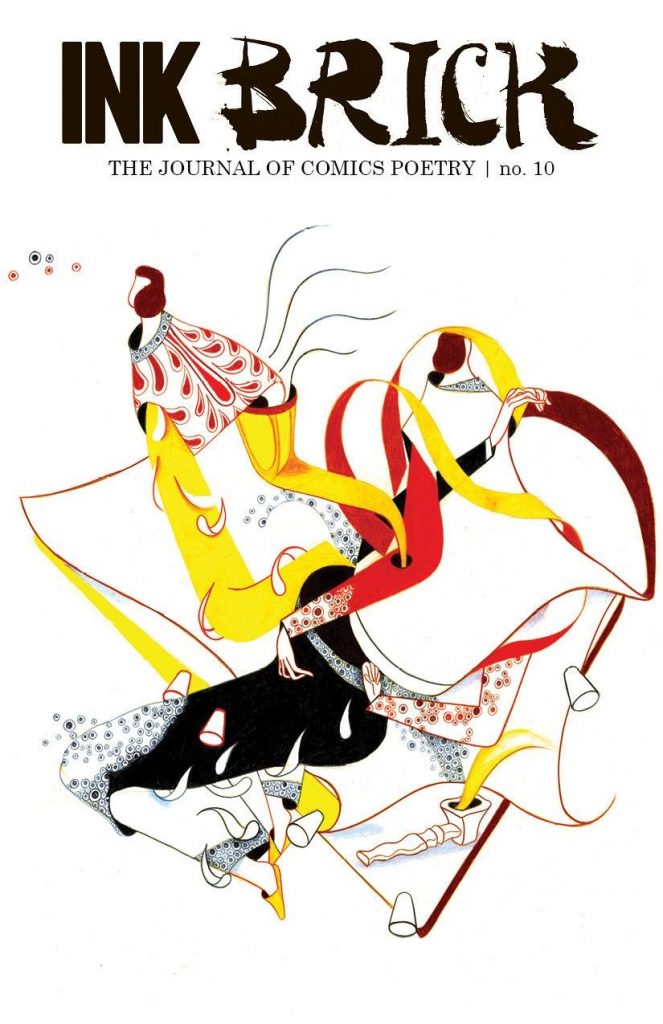

After nearly eight years of being at the forefront of what could fairly be called a “quiet revolution” in regards to the developing genre of comics poetry, groundbreaking anthology Ink Brick is calling it a day. There are two ways to look at this, of course, depending on if one is the “glass half full” or “glass half empty” sort: one could either take it as a sign that comics poetry isn’t yet firmly-established enough to sustain a “prestige” anthology of its own, or one could take it as a positive sign that the medium is healthy enough that the publication that helped raise it to its current state of development is ready to let it leave the nest and fly, its “hatchling” phase now safely over and done with.

I happen to lean toward the latter myself, albeit with a dash of hard-and-fast realism thrown in to temper such an admittedly idealistic outlook: in point of fact, any labor of love — and Ink Brick has always fit that description, from its 2013 inception right up to the present — is going to have a finite lifespan, the vagaries of small-press publishing being what they are, and with that in mind, knowing when the time has come to put the baby to bed is crucial. To their credit, Ink Brick publisher Alexander Rothman and editors Paul K. Tunis and Alexey Sokolin appear to have opted to leave, as the sports cliche goes, “at the top of their game,” and their tenth and final volume presents a wide variety of contributors old and new that comprise a dynamic mix of the stylistically familiar and the far less so, the established and the experimental, that fully engages readers from the first page to the last.

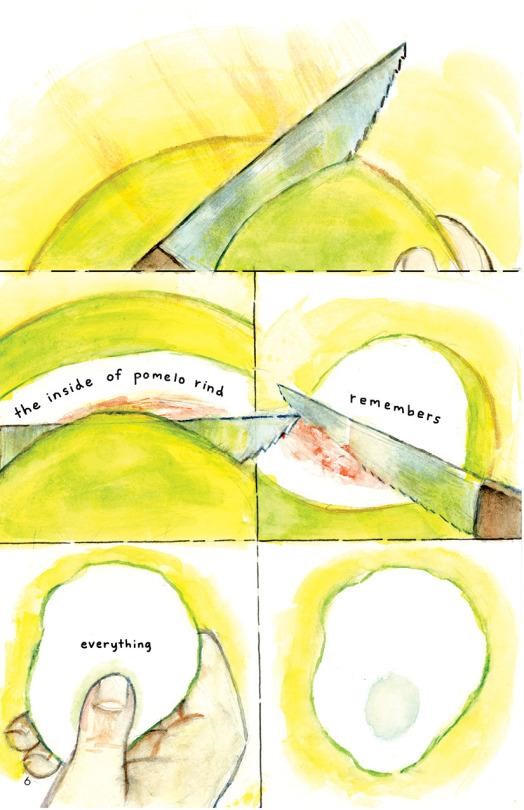

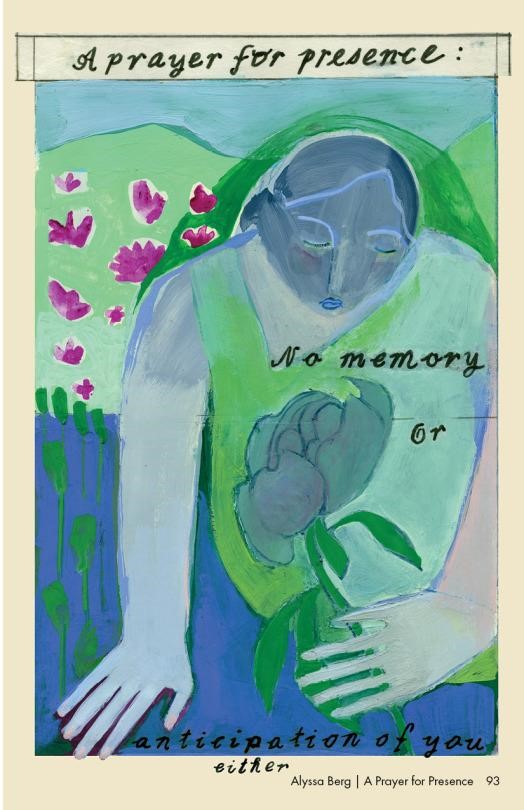

It could, of course, be argued that all comics poetry is “experimental” to one degree or another, and. while there’s more than a grain of truth to that, certain recurring motifs and artistic choices have become mainstays as the medium has developed: watercolors and colored pencils lend themselves quite well to the delicate and subtle nature of much visual poetry and are represented herein by artists Daryl Seitchik, Madeleine Witt, Laurel Lynne Leake, Alyssa Berg, Andrew White, and Thomas Hamlyn-Harris. Minimalist pencils often go hand in glove with minimalist verse, as Warren Craghead and Bianca Stone more than ably demonstrate. Fluid, free-form text is a natural fit for Keren Katz’s textured patterns and borderless panel arrangements. Deep, rich, inky blacks with woodcut-style undertones lend themselves to the emotional and thematic darkness of Allie Doersch and John Hankiewicz’ pieces. Don’t take that to mean that there’s anything terribly conservative or tepid about the work any of these artists turn in, rather their poems demonstrate a veteran sensibility that is familiar with both what they wish to communicate and how they wish to go about doing it.

Taking the road somewhat less traveled, relatively speaking, are Noemi Charlotte Thieves, who uses photo collage to relate an emotive “story” about love lost but still yearned for, and co-editors Sokolin and Tunis, who utilize deliberately incongruent experimental computer-generated imagery and “splatter effect” colors juxtaposed with detailed ink drawings, respectively, to illustrate two of this volume’s most purely interpretive pieces. Likewise,Noel Suthers, for her part, utilizes a single image to complement a densely-worded slice of poetically communicated history. Kevin Czap tells a childhood reverie by means of minimalist verse paired with fluid-but-unambiguous art. Kimball Anderson marries the cosmic with the deeply personal by means of jet-black backgrounds interspersed with precisely-chosen flashes of white, blue, and red. Mario Klingermann meshes the digital and the organic without necessarily favoring either. Ileana Haberman-Ducey runs an ambitious gamut of art styles in her wordless piece, while publisher/editor-in-chief Rothman sticks with a strict four-panel-grid format, but radically changes color schemes every two pages to tell one of the most tonally consistent and “tight” poems in the book. Some of these selections are less successful than others in terms of clearly communicating even a vague, much less a specific, artistic intent, but I give all of them tremendous credit for their ambition, and I recognize in each the kernel of a strong idea somewhere, even if the efficacy of its means of expression is somewhat muddled.

With a collection such as this, however, what’s every bit as important as the works presented is the order in which they’re assembled — and it’s certainly no easy task to establish and maintain a kind of visual and emotional “flow” when every poem is an entirely unique expression unto itself. Editing a book of this sort, then, requires an intrinsic trust in one’s own feelings, every bit as much as it does an eye for strong work. To say that Tunis and Sokolin pull this off rather beautifully is, if anything, an understatement. In point of fact, their “running order” is incredibly smooth, and when it’s not absolutely and precisely seamless by design, they cushion the transitions between works with several one-page poems by Stone or Berg that tie things together while simultaneously serving as subtle “reset points” for readers. Also worthy of note is a selection of thematically-linked student poems curated by Tom Hart that are placed more or less smack-dab in the middle of the volume and are effective as an intermission of sorts between the first and second halves of the book.

Upon reflection, it’s clear that the goals for Ink Brick number ten were twofold: to serve as a strong self-contained comics poetry anthology in its own right, and to offer a heartfelt “thank you” and “farewell” to long-time readers. It succeeds admirably on both counts and reassures us all that even without it, comics poetry is here to stay and its future is well and truly limitless.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply