Jubran Khalil Jubran, known in English as Kahlil Gibran, was a writer, artist, and political activist. He was born into a Catholic family in Lebanon in 1883 and moved to Boston with his mother and siblings when he was twelve. It was there that he was first encouraged as an artist. He lived between the U.S., Lebanon, and Paris where he studied art. His early writings were in Arabic. His first novel brought condemnation from the Church and the Syrian government for its feminist leanings. After returning to the U.S. in 1911 his first book written in English, a volume of poetry called The Madman, was published by Alfred Knopf. These poems tackle some of the same subjects as his later and most popular book, The Prophet. By the time The Prophet was published in 1923, his activism has died down and he was more focused on artistic pursuits.

Though the initial sales of The Prophet were modest, it has never been out of print and is one of the best-selling and most frequently translated books available, which is no surprise. In lovely language, Gibran lays out a worldview of mindfulness and personal responsibility within the context of our interconnectedness, both as people and with nature. Elements of his Catholic upbringing can be seen in the book, as well as Sufi mysticism. There are other apparent wide-ranging influences such as William Blake, Nietzsche, Walt Whitman, and the Syrian poet Francis Marrash.

Even those who haven’t read the book have often encountered sections of it quoted at weddings and funerals. Excerpts of the poems on love, marriage, and death are often found on greeting cards and in memes across the internet.

The original book is stylized as a series of philosophical prose poems, delivered by a man called Almustafa. He has been living in exile for twelve years in the mystical land of Orphalese. When the ship of his countrymen finally arrives to take him home, the populace, led by the seeress Almitra, requests he recounts for them his wisdom. He addresses them on a variety of subjects, from the above-noted love, marriage, and death to commerce, talking, crime and punishment, work, laws, eating and drinking, children, religion, good and evil. self-knowledge, beauty, time, and more.

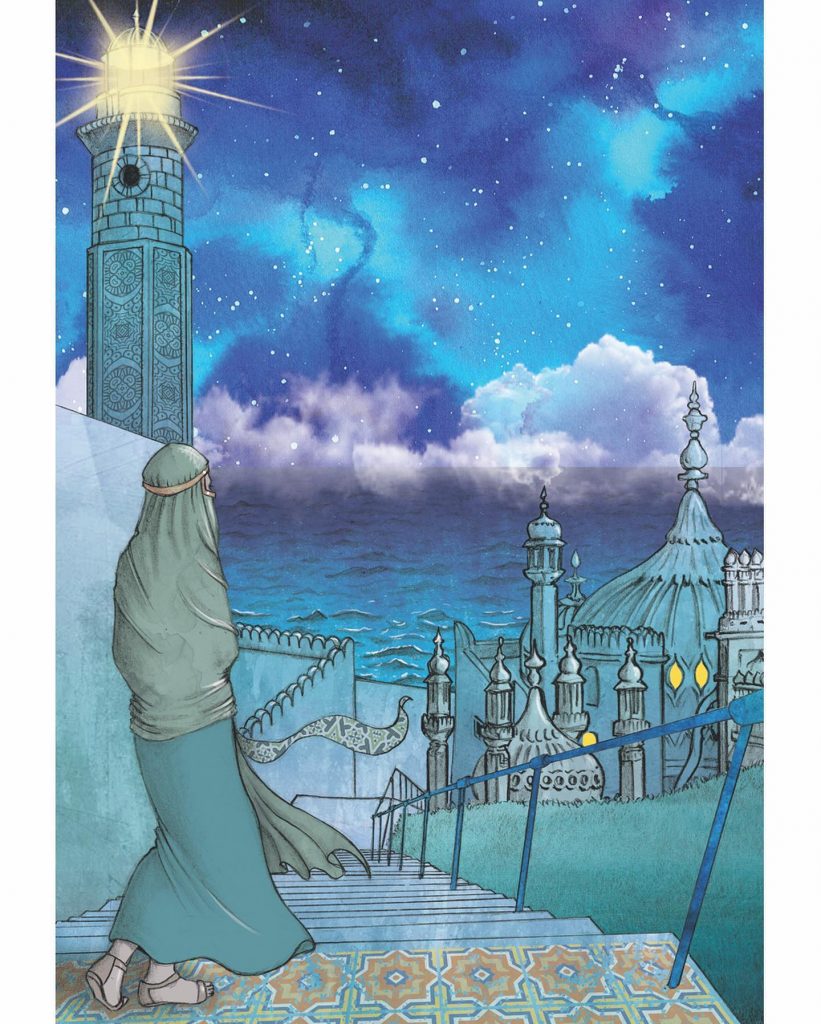

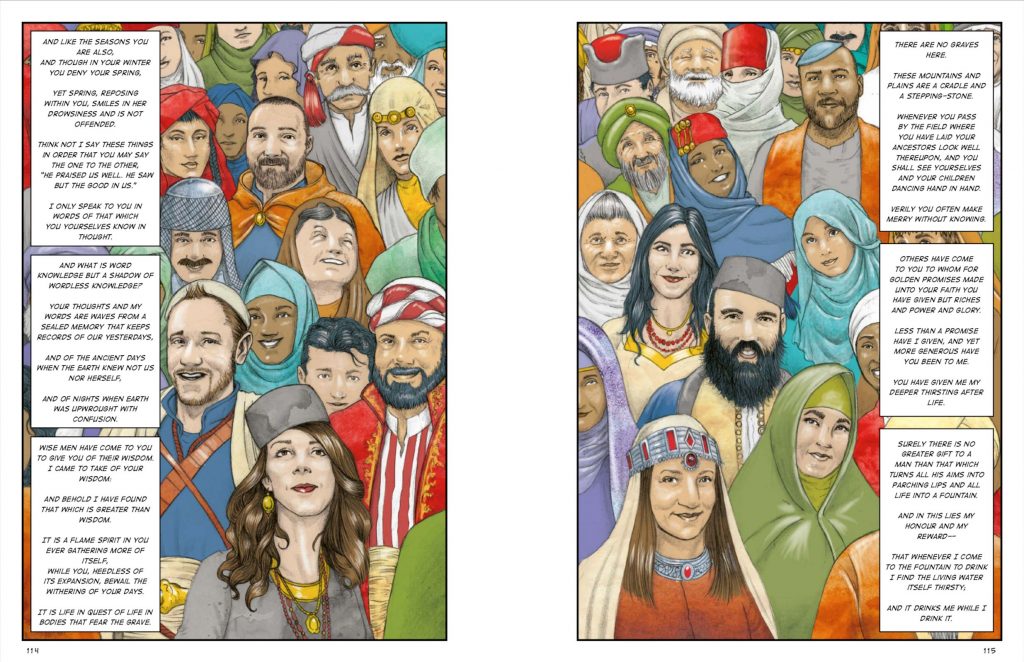

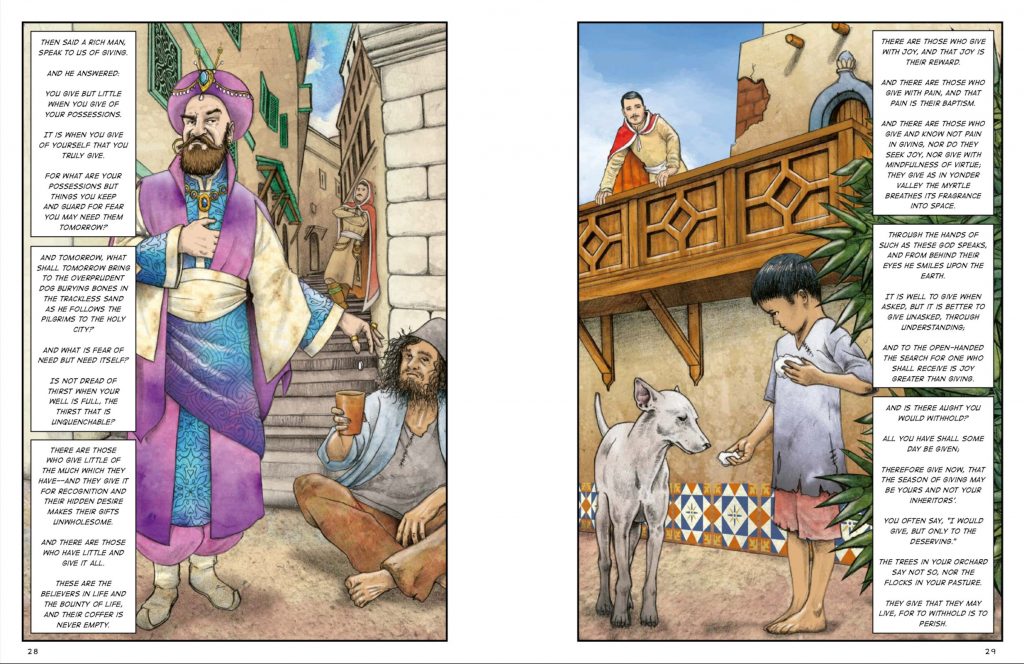

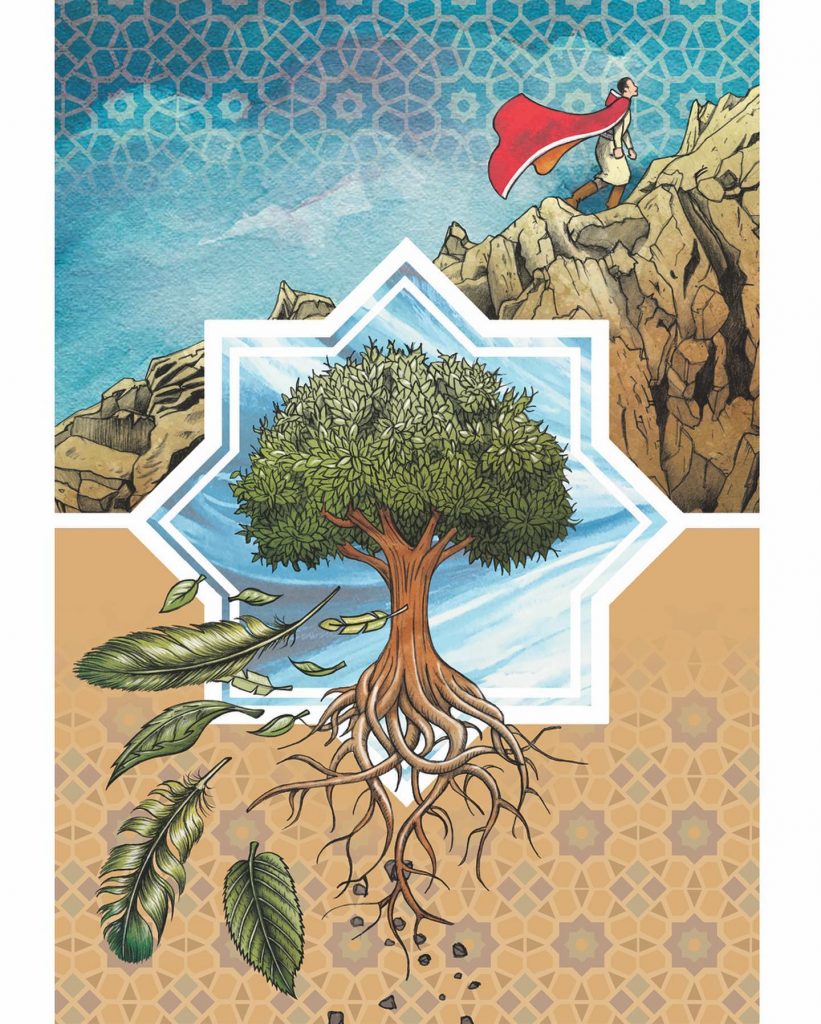

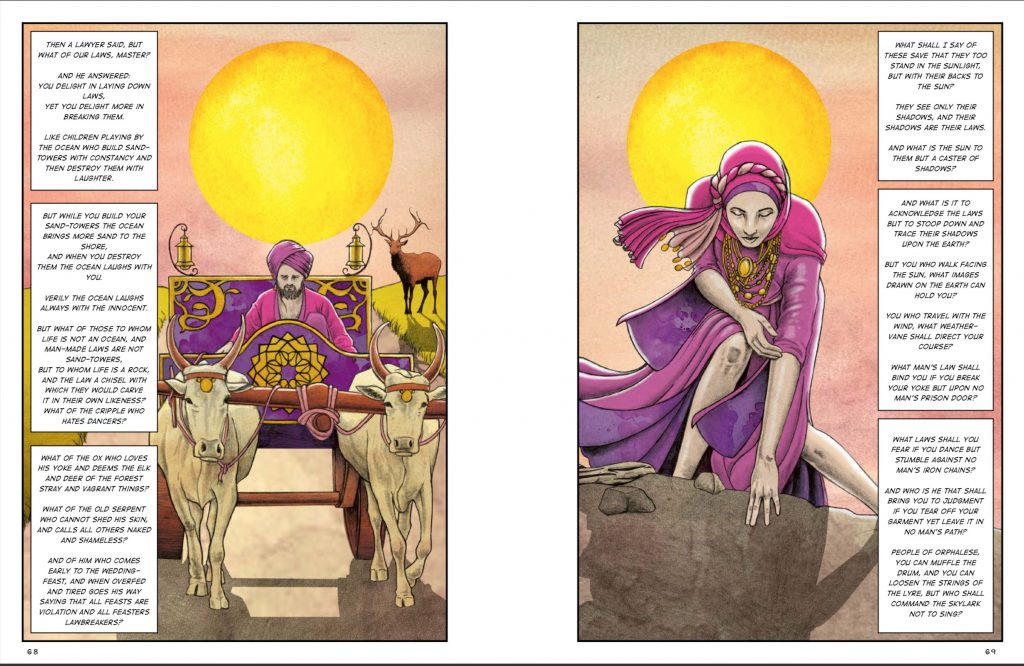

Pete Katz’s adaptation retains the original poetic text, illustrating it beautifully. Orphalese is rendered in vibrant tones, with many familiar middle eastern motifs. The city is full of minarets, onion-domed towers, floral and geometric tiles, open air markets, and fountain filled riyads. The faces represent all ages and are clearly a cross-section of the Mediterranean/ Middle Eastern world. The preamble to the poems is delivered in fairly standard comic book format with word balloons and the pages broken into frames. The poems are in caption boxes that frame (mostly) full-page illustrations that either evoke the sentiments of the poem or expand on the messages in subtle ways. The representations of friendship spanning a lifetime are heartwarming. The illustrations for “On Buying and Selling” are set in a marketplace, but don’t only focus on produce, livestock, and products, they include arts and skills that must also be paid for – in this case, jugglers, musicians, and negotiators.

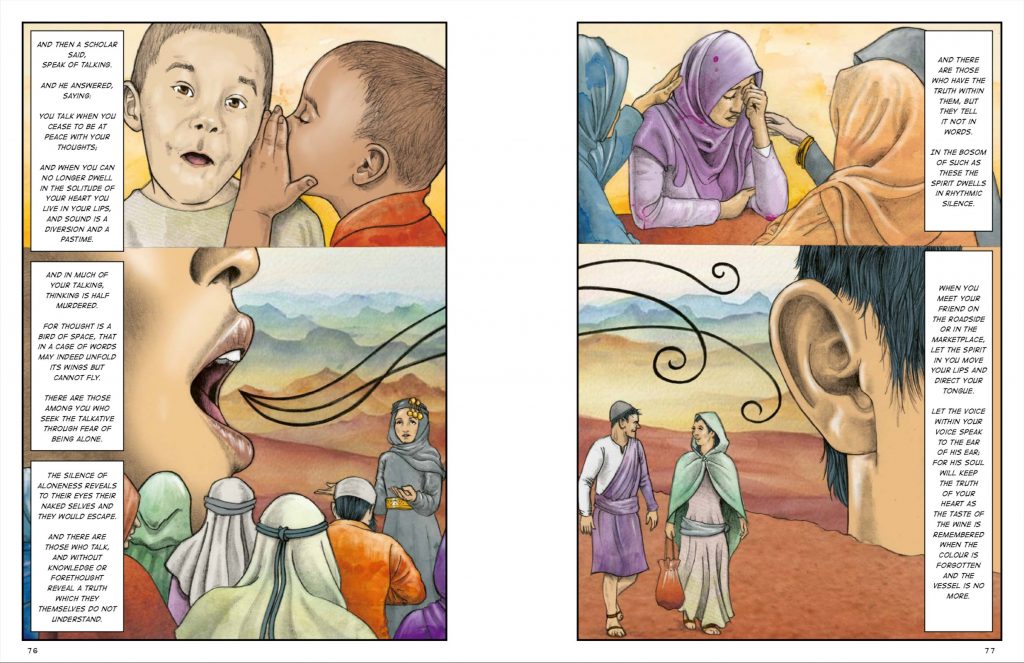

The poem about talking is illustrated with several vignettes. One where a woman is silently comforted by friends deepens the passage:

On Talking

“And there are those who have the truth within them, but they tell it not in words. In the bosom of such as these the spirit dwells in rhythmic silence.”

I wonder how Gibran, with his budding feminism, would respond to the notion of women suffering in silence?

The images for some of the poems are less literal and often build meaning with symbols or repeat an aspect of the allegory. For example, the images for the poem “On Freedom” depict a bird freed from a cage, a man breaking his shackle, as well as the weapons of force. The pages “On Learning” are filled with tools from the near East – a couple of drawing compasses, an abacus, an astrolabe, scrolls, and a celestial globe.

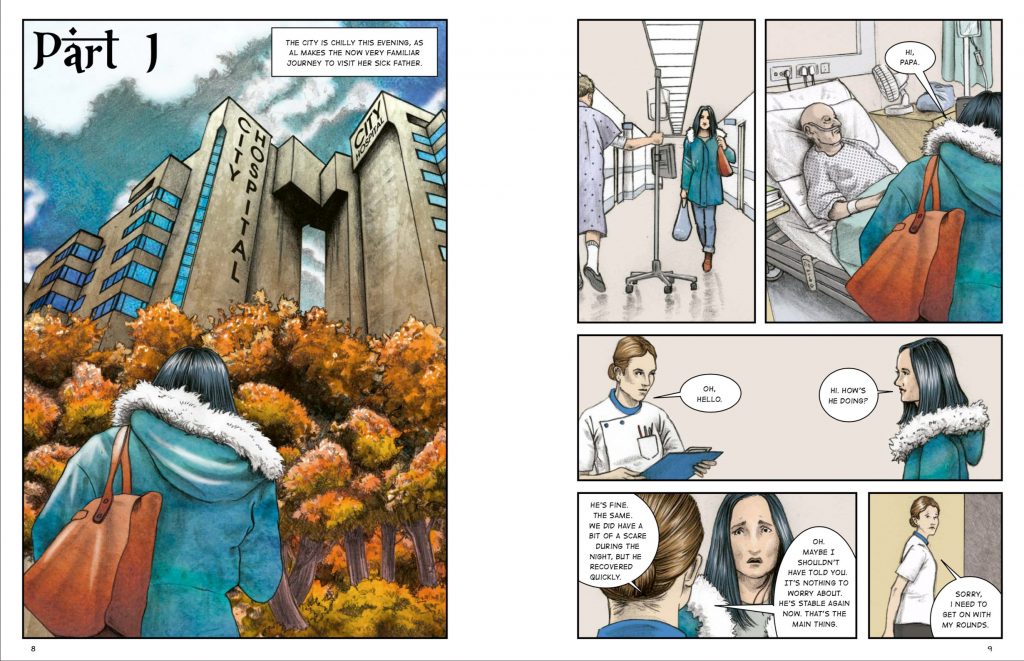

Grounding the mystic wisdom of the poems in the contemporary world is the story of Al, an artist whose life has been upended by her father’s protracted hospitalization. Her friend gives her the book as both a potential comfort and to help her pass the time in the hospital. The adaptation moves between the beauty and wisdom of the poetry and Al’s struggles with many of the questions contained in The Prophet. In the process, she discovers her own connections to the book. The modern world is rendered as slightly less vibrant. Many of the settings – living rooms, hospitals, public pools – feel more mundane, but give Al a chance to discuss and put into practice what she is learning. Sometimes it is hard to see all of the topics at play. Some lend themselves to Al’s situation more readily than others. The language of The Prophet is elevated, and it is nicely contrasted with the mostly straightforward conversations that Al has with her friends. This emphasizes the focus on actions and intentions over words that come up again and again in the poems.

I first encountered the work of Kahlil Gibran in high school. I was drawn to his philosophy of love and acceptance and his vision of a God that resides in everyone. A teacher scoffed at the work as sophomoric, which I found very amusing, being a sophomore. In college, I “moved on” and found myself drawn to Kafka, Teresa of Avila, Descartes, and Mary Wollstonecraft, largely leaving Gibran behind. The Prophet, Sand and Foam, and The Madman have sat on my shelves for years. Reading this adaptation, however, reminded me of the power of Gibran’s vision of a world guided by the deep longings of the soul to be at one with the universe, to touch God. I also realized how much his fundamental stance of being in mindful gratitude and playful interaction with both other people and nature had taken root in my thinking. It may seem obvious that our joy and sorrow spring from the depth of our caring, but that is easy to forget. It may be deemed naive in our culture to look at giving and receiving through Gibran’s eyes, but as the following excerpts point out, it could be a guiding principle for solving some inequities in the world.

On Giving

“There are those who give little of the much which they have—and they give it for recognition and their hidden desire makes their gifts unwholesome.

And there are those who have little and give it all.

These are the believers in life and the bounty of life, and their coffer is never empty.

You often say, “I would give, but only to the deserving.”

The trees in your orchard say not so, nor the flocks in your pasture.

They give that they may live, for to withhold is to perish.

Surely, he who is worthy to receive his days and his nights, is worthy of all else from you.

And you receivers—and you are all receivers—assume no weight of gratitude, lest you lay a yoke upon yourself and upon him who gives.

Rather rise together with the giver on his gifts as on wings;

For to be over mindful of your debt, is to doubt his generosity who has the freehearted earth for mother, and God for father.”

Of course, not all is sweetness and light. Gibran makes note of hard lessons, even from corners that we like to think of as safe harbors. In one of the less frequently quoted sections from “On Love, “ he writes:

On Love

“When love beckons to you, follow him,

Though his ways are hard and steep.

And when his wings enfold you yield to him,

Though the sword hidden among his pinions may wound you.

And when he speaks to you believe in him,

Though his voice may shatter your dreams as the north wind lays waste the garden.”

The Prophet repeatedly calls on his listeners to see the good in one another and to respect one another by being patient, kind, compassionate, and aware that we are all souls treading on the Earth for a short time. Gibran sees much of the individuals’ failings as the failings of society as a whole. As these excerpts from “On Laws,” and “On Crime and Punishment” illustrate:

Laws

But what of those to whom life is not an ocean, and man-made laws are not sand-towers,

But to whom life is a rock, and the law a chisel with which they would carve it in their own likeness?

What of the cripple who hates dancers?

What of the ox who loves his yoke and deems the elk and deer and the forest stray and vagrant things?

What of the old serpent who cannot shed his skin, and calls all others naked and shameless?

And of him who comes early to the wedding-feast, and when over-fed and tired goes his way saying that all feasts are violation and all feasters lawbreakers?

Crime and Punishment

Oftentimes have I heard you speak of one who commits a wrong as though he were not one of you, but a stranger unto you and an intruder upon your world.

But I say that even as the holy and the righteous cannot rise beyond the highest which his in each one of you,

So, the wicked and the weak cannot fall lower than the lowest which is in you also.

And as a single leaf turns not yellow but with the silent knowledge of the whole tree,

So, the wrong-doer cannot do wrong without the hidden will of you all.

Like a procession you walk together towards your god-self.

You are the way and the wayfarers.

And when one of you falls down he falls for those behind him, a caution against the stumbling stone.

Ay, and he falls for those ahead of him, who though faster and surer of foot, yet removed not the stumbling stone.

And this also, though the word lie heavy upon your hearts:

The murdered is not unaccountable for his own murder,

And the robbed is not blameless in being robbed.

The righteous is not innocent of the deeds of the wicked,

And the white-handed is not clean in the doings of the felon.

Yea, the guilty is oftentimes the victim of the injured,

And still more often the condemned is the burden bearer for the guiltless and unblamed.

You cannot separate the just from the unjust and the good from the wicked;

For they stand together before the face of the sun even as the black thread and the white are woven together.

And when the black thread breaks the weaver shall look into the whole cloth, and he shall examine the loom also.

Reading the adaptation made me think again about the beauty of poetry, especially as April is National Poetry Month. It also made me realize how seemingly simple truths can resonate when more convoluted philosophies can be difficult to access and harder to put into daily practice.

Overall, Pete Katz’s adaptation of The Prophet is a satisfying and accessible way to enjoy the well-loved classic. It is a wonderful introduction for someone unfamiliar with the book. For those who know the work, it is a lush re-imagining.

Leave a Reply