Poetic language is often highly symbolic, dense, and abstract, taking readers out of their comfort zone. In much the same way, comics-as-poetry not only uses compact, frequently cryptic imagery in order to force the reader to engage it outside of the framework of a conventional narrative, it also adds an additional layer of complexity when the reader is also asked to grapple with the tension between word and image.

Conventional comics make a point of trying to make the reader forget about their underlying structure. Exaggerating and highlighting structure in comics-as-poetry can be a way of teasing out emotional and symbolic meanings. Closely reading this relationship is essential in understanding the work of John Hankiewicz, one of the premier cartoonists who works in the medium of comics-as-poetry.

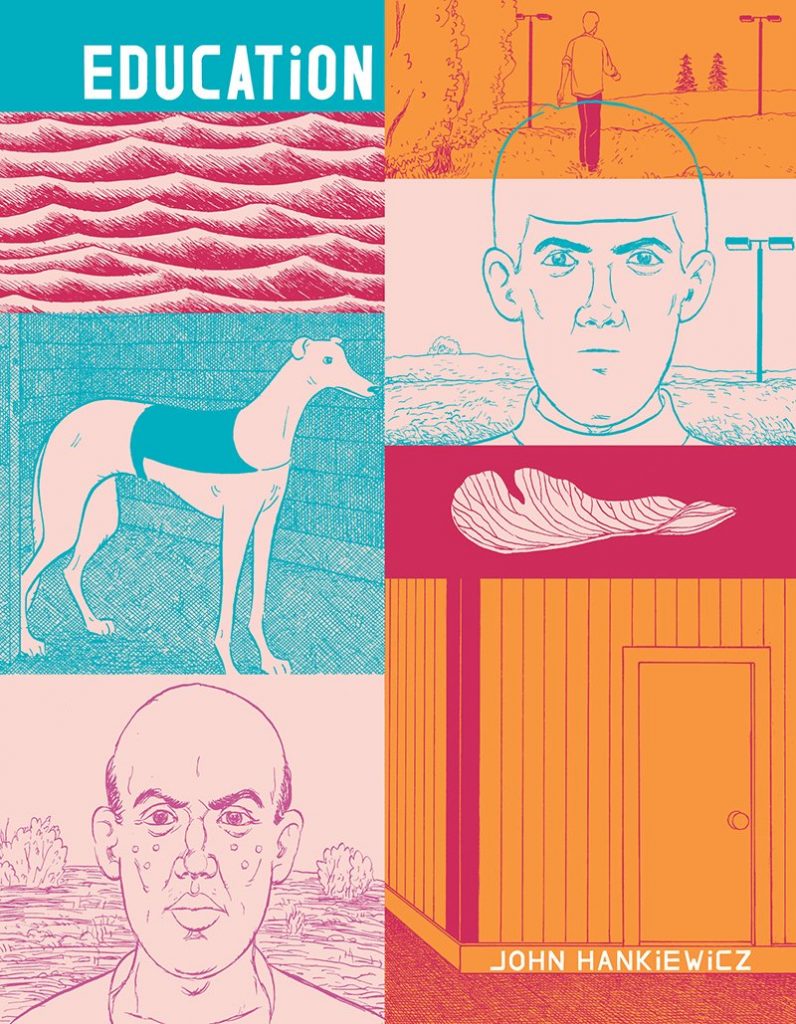

Hankiewicz has long created stories with an enigmatic, elusive quality that fully employs the language of comics, featuring conventional page and panel designs recognizable to any reader of the form. He uses standard four and six-panel grids, for example. He draws in a naturalistic style. Though on the surface level, his iconic imagery seems familiar, his comics do not have a traditional, linear, plot-driven narrative. Rather, they have an emotional and cryptographic chronicle in which meaning is more challenging to tease out.

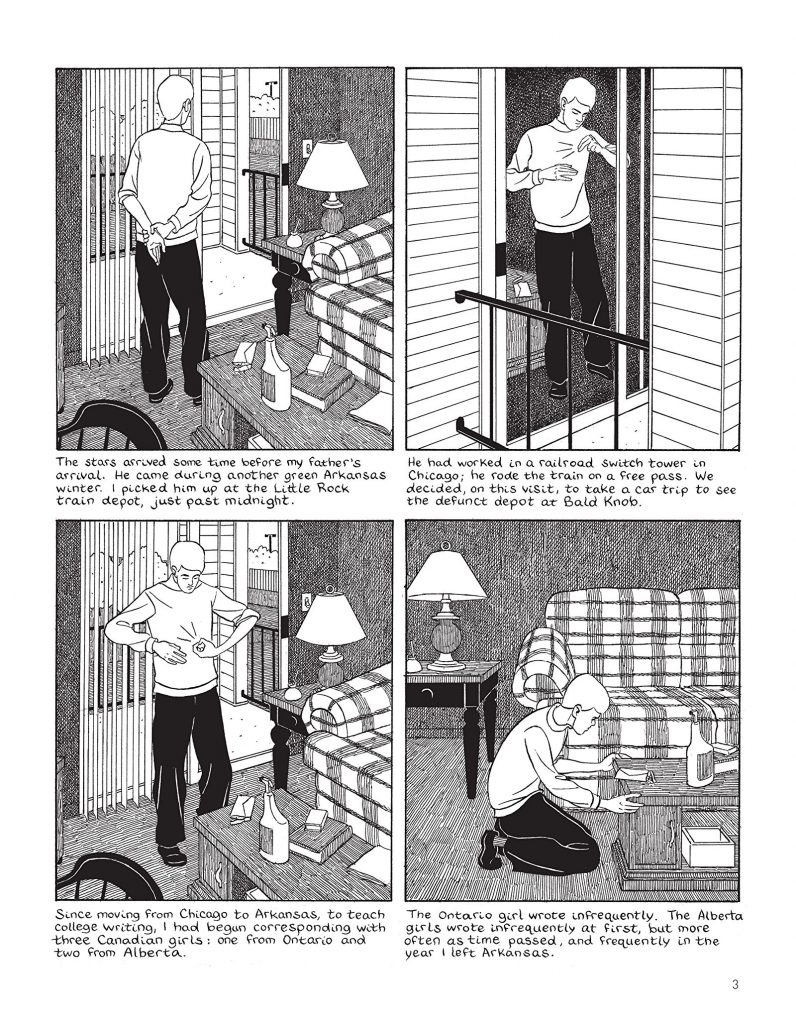

Hankiewicz’s 2017 book Education (Fantagraphics Underground) provides most of the textual and narrative clues the reader needs on its very first page. The first line, “The stars arrived sometime before my father’s arrival,” is deliberately cryptic, but Hankiewicz soon explains that an envelope full of perfumed gold stars has been sent to the nameless protagonist by a Canadian woman he’s corresponding with. Also, the protagonist’s father is coming to visit him in Arkansas in order to check out an abandoned railroad station. The narrative is written in the first person.

The relationship between text and image is clear in the early going. In the first six pages, the narrator meets his father in a hotel room, they exchange gifts, and they start their road trip. The narrator notes that the woman who had sent him the gold stars, “the scented, gleaming, insidious gold stars,” had “annoyed and offended him.” He notes that he had encouraged her to write explicit, erotic letters at first, but that this particular letter with the gold stars led him to stop replying. It was too late, however, as “The longer I lived with the scented stars, the more the scented Alberta girl troubled my mind. She had broken out of Canada and into my life.“

Hankiewicz’s work, for all of its poetic and formal crypticness, has always been about the difficulty of human connection. This is especially true of Education, as the narrator’s actions belie his stated needs for intimacy. He is the ultimate unreliable narrator, as the images we see can be interpreted as dreams, fantasies, or conflated memories. From the beginning, communication is muted and stilted. In the early pages, when father and son briefly speak, the word balloons never point to the speaker. Instead, the reader sees the person spoken to, and their conversations are banal.

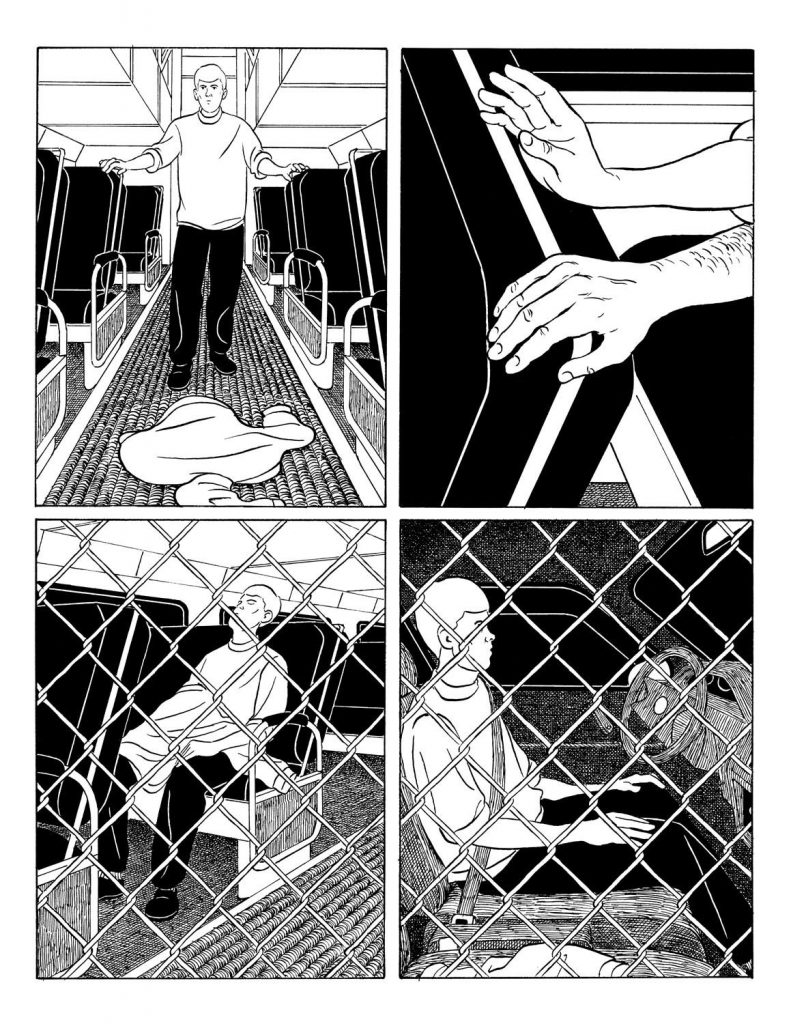

After this, the relationship between text and image fractures. Most of the images involve a series of interactions between the narrator’s father (frequently pictured as a very young man) and a mysterious, playful, and mischievous young woman. These interactions are flirtatious, playful, and sometimes absurd. Throughout the book, the narrator keeps finding the annoying gold stars and picks them off his body. However, he never interacts with the young woman, as he attempts to erect barriers against this woman who has “invaded” his life.

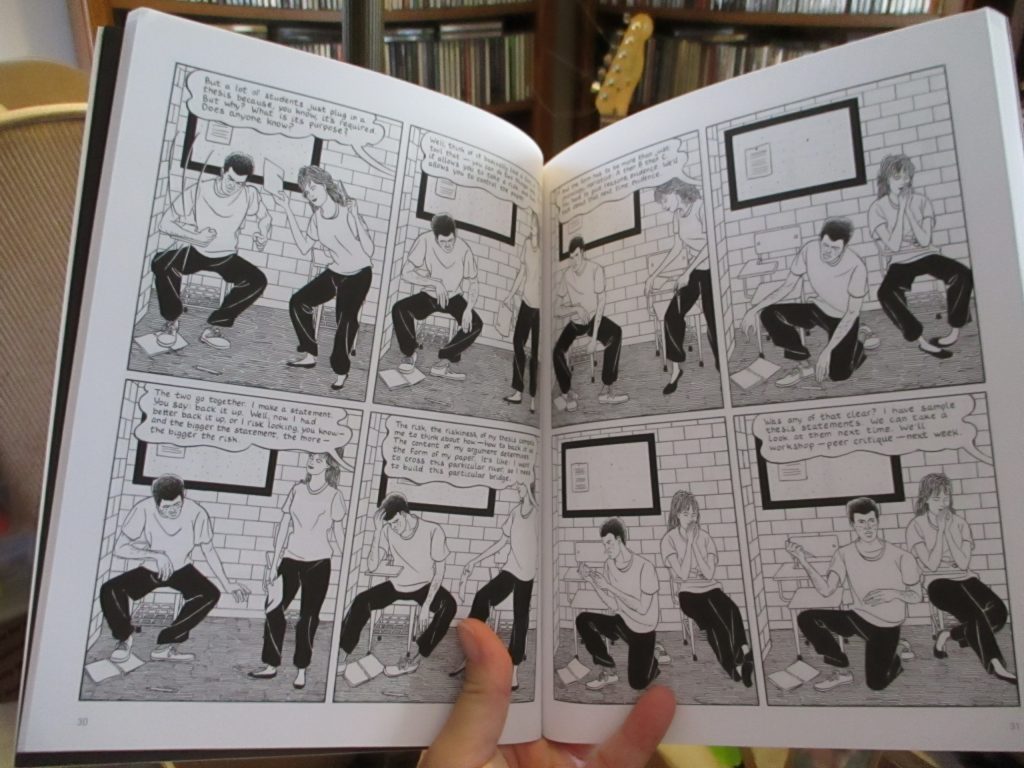

The images shift to a classroom, but the only students we see are the dad and the woman. The only voice we hear is that of the teacher, who goes on and on about the next writing assignment and what he expects. It becomes obvious in the course of the book that the narrator is the teacher. These sequences are reveries involving his increasingly inappropriate and desperate comments to the class, begging for validation, along with his fantasy images of his dad and the woman. The images find her needling, poking, and prodding his dad because that’s what thinking about her makes the narrator feel.

This is ultimately a book about the treacherous relationship between memory and intimacy. He believes that he’s trying to be open and vulnerable, but the lingering fantasies belie that belief. He’s more interested in the idea of being beloved, of being a teacher who connects with his students, than actually doing it. He wants all of his intimacy to be only on his own terms, where he’s in a position to control it.

Crucially, another narrative emerges: it is the text of the letters written between the narrator and the woman, rewritten as a conversation held only in his head. It is revealed that she is a teacher, too. The details of the narrative are achingly intimate and then disturbing, as she claws him with her blue nails and later won’t let him out of her classroom. These are the words and images that he can’t get out of his head, the ones that have infiltrated his memories and interactions. What prevents him from manipulating these memories like any other? It’s the smell of the perfume on the omnipresent gold stars.

Smell is the sense most evocative of memory. It clings, it lingers. The perfumed gold stars are cloying, invasive symbols of a relationship the narrator loses control of. Indeed, given the written nature of their correspondence, there’s a sense in which the narrator loses control of his own narrative. She takes the relationship into areas he’s not ready or willing to explore, especially with regard to power relationships. She wants to claw his flesh and he tears up grass in response; this is a frequent visual metaphor in the book. The perfume traps him in this memory and jumbles his perceptions. He pictures his father with her because he doesn’t want to think of himself in this position.

Hankiewicz suggests that the narrator’s human relationships are contingent on his ability to control them. He only interacts with his father through a series of safe discussion topics. That these topics are repeated throughout the book when the other narratives spin out of control is no coincidence. His interactions with women are long-distance, first of all, and, even then, he prefers another woman who more innocently sends him twine in the mail. She’s more “Canadian,” somehow, which seems to be code for an American’s understanding of Canadians as nice and thus submissive. His interactions with students are mediated entirely in writing, and he despairs that the students are not reading what he is writing to them–again, from a position of authority.

His intimacy with others is fake, and getting called out on it with the gold star Canadian woman is something he can’t shake. She’s giving him an education he doesn’t want but can’t let go of. When he’s in her schoolroom in the fantasy scenario she evokes (or he perhaps imagines), he can’t breathe. He’s suffocated by real intimacy and the possibility of not having a dominant power position. He wants her to let him go, but she won’t allow it. He brought her into his life, and now she’s living in his head, accentuated every time he finds a gold star on his body or can’t breathe because he is overwhelmed by their sweet smell. His unwillingness to open himself up has trapped him.

In his work, Hankiewicz explores ways in which the mundane becomes alien and threatening, how communication can be a form of aggression, the madness that isolation can induce, and the possibility that we are essentially doomed to be isolated from both the world and each other. At the same time, this quest for connection is our only chance at creating meaning and purpose, impossible as it may seem. Hankiewicz gets at this by balancing the mundane and the absurd in his imagery, challenging the reader to grapple with these juxtapositions as well as their varied relationships to the text. It has a hermeneutic quality, where, in order to understand individual images, one must have a grasp of the overall themes, but the themes themselves are built through the careful, deliberate structure of the comic. The deadpan, naturalistic quality of Hankiewicz’s images belies the desperate intensity of Education’s emotional narrative, allowing readers the opportunity to make connections on a number of different levels.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply