When I think about comics poetry, I think about structure; how less is more, how text and image are multiplicative. I also think about how short most of these pieces tend to be. There’s a distillation of intent in most comics poetry, and that distillation lends itself to minimal page counts, the same as traditional poetry. But what happens when you hold on to the core concepts of comics poetry and allow those concepts to breathe? What happens when you give the image and text a chance to expand past a few pages? Kevin Czap is looking for that answer with their latest comic, Four Years.

Four Years is Czap’s new webcomic, which they started serializing on Patreon in 2018. Each part of Four Years was published individually through Czap Books, and Czap recently collected the first three parts of the series in a 44-page perfect-bound softcover book in 2019. The main character of Four Years is Betty Yaris, a 32-year old woman who decides to finally get her ears pierced. The comic focuses on the relationships that Betty has with a group of close friends and the future she sees for herself in a place of safety and support.

Czap is a cartoonist whose work often has a poetic or lyrical bent; their 2015 comic Fütchi Perf mimicked the form of a comics “album,” with individual short stories acting as the “tracks” that comprised the larger work. The album of Fütchi Perf was based on the idea of a utopic Cleveland, where Czap has previously lived. With Four Years, Czap takes the utopic energy of Fütchi Perf and commits it to a longer and more sustained narrative.

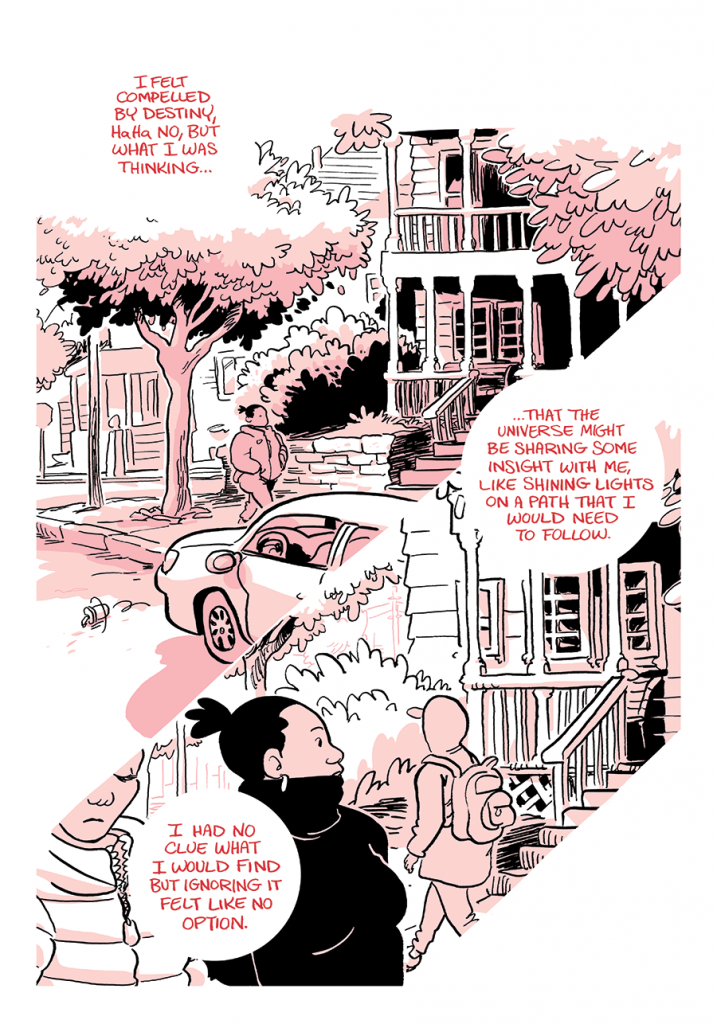

Czap’s cartooning in Four Years is as accomplished as ever, a smart blend of the soft and fluid. Their use of a limited color pallet, similar to Fütchi Perf, is an interesting decision — Fütchi Perf was printed using 2-color risograph, so the choice to use a limited pallet was as much a printing and materials constraint as it was an aesthetic choice. Again, it’s a decision that pays dividends. The limited colors emphasize the characters and their conversations, pulling the reader into the blur of community.

The majority of the book’s text is snippets of dialogue, where Betty and her group of friends discuss whatever is going on; whether the group is watching television or planning a vacation together, this naturalistic dialogue acts as a complement to Czap’s fluid line. This more lengthy, humanist construction is contrasted with a series of monologues where characters directly communicate with the reader. Czap uses color and paneling to direct the reader’s eye and understanding. It’s a smart and intuitive use of the tools of cartooning to layer meaning over the presented conversations. The interplay of these two texts seems like a gentle rebuttal to the terseness of other types of comics poetry.

The central thematic element of Four Years is the concept of growth. Plants play a key role in the comic, and they appear in abundance in situations where Betty is most supported by her friends. The flowers in those most intimate moments are explosive, blooming all over the characters and, at times, sprouting from their knees and hair and faces. These flowers act as a visual metaphor for personal and interpersonal growth, and they emphasize the organic nature of friendship and love. Czap’s flowers are striking in their beauty and fluidity. Visually, they sprout most wildly when Betty is in the presence of her chosen family, emphasizing the power of creating community.

Sprouting and growing flowers are not a unique metaphor, but they are rarely used this effectively. The metaphor of the person as a seed is a powerful one, and it resonates throughout Four Years. Betty sees herself as long-dormant, now finally awoken to change. Just as if a seed is planted in healthy soil and cared for, it will bloom, so, too, will a person. If the person/seed is planted in the “good earth” of supportive friends and family and is carefully tended, nurtured, and loved, then their blossoms will be without parallel.

Growth also has an end-point; the seed in good soil leads to first growth, maturation, then buds, and finally blossoms. It’s a process and that process is echoed in Betty seeing a person who lives near her block, a person who can really only be described as “future Betty.” This “future Betty” plays in a band and, to Betty, seems like a brilliant light. Future Betty is older, yes, but is also presented as more vibrant and world-wise. It doesn’t seem to me as though this person is actually a time-traveler. Rather, she is another metaphor; in this woman, Betty sees herself, but, more importantly, she sees in her a path forward. “Future Betty” is a route for personal growth, an endpoint to aim “current Betty” at. Betty sees this woman as the person she could be. Subtly, Czap seems to indicate that this “future Betty” is a path that is visible only because of the support that Betty has from her chosen family.

This installment of Four Years covers the first half of the planned story of Betty Yaris and her friends, but it’s clear that Czap has settled into a set of themes that inform their work. The ideas of utopia, growth, community, and love that were present in Fütchi Perf are presented in Four Years in a more personal and direct way. If Fütchi Perf relied on an abstracted and universal humanity to lean into these themes, then Four Years is the opposite. Four Years is the poetry of a person who creates intimate visions of their lived self, and, as a result, finds universality. That intimate universality makes Four Years much more poignant than Czap’s previous work. How future “stanzas” of this poem read and evolve our understanding of these themes is unknown, but for now, Four Years is an enchanting dialogue between the what-is and the can-be.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply