Today we’re pleased to reprint a 2016 essay from Alexander Rothman, a cartoonist and poet whose anthology INK BRICK ends its 7+ year run with its 10th issue. Our critic Ryan Carey has a review of that final issue here.

“…it is by their syllables that words juxtapose in beauty”

Charles Olson

I call the work that I create and publish “comics poetry.” But what does that really mean? For me, the easiest way to get at the hybrid form is to think about its constituent parts—poetry and comics.

So what is poetry? I understand it as the purest example of a form where the medium is language. Other written forms have ancillary concerns—for instance, plots for novels, arguments for essays, and performances for plays. Of course poems can take on these concerns, and, of course, language plays a central role in these other forms. But at the end of the day, more than any other practitioner, a poet is just left with words. When she sets out to work, she must ask herself, “How do I solve this creative problem with language?” or “What else can language do?”

Put another way, poets spend most of our time rooting around in language’s toolbox. We know that the earliest poems arose from oral traditions. To enhance the telling of histories and epics, performers developed breath-control strategies, mnemonic rhythms, and so on. Generations of poets have devised countless additional ways to harvest the expressive potential of words. We draw upon their denotative and connotative meanings; their sounds, in or out of structured meters; their enjambment across lines; their spatial arrangement on the page… Every last aspect of language is there for the poet to use, break, reinvent.

That’s my working definition of poetry. Do I think it’s the only one or the “correct” one? Of course not. It’s broad, perhaps overly so, but I think it serves as a container for the myriad, fractious things that have been called “poetry.” What else binds sestinas, slam, caligrammes, and haiku?

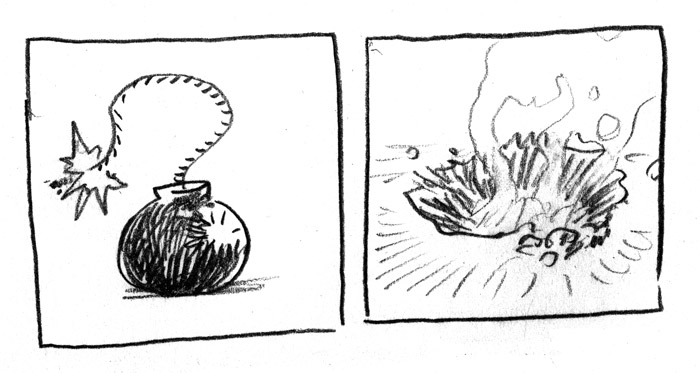

It’s similarly difficult to define “comics” in any comprehensive, meaningful way. I approach the form as one that uses images the way other kinds of writing use words. Its basic unit is juxtaposition: place two or more images next to each other, and some semiotic impulse in our minds can’t help but connect them. This isn’t necessarily the process Scott McCloud calls “closure,” where we knit discrete images into unbroken narratives—for instance, seeing a drawing of a burning fuse, then another of smoldering rubble, and somehow providing the missing explosion between them. It could be something like that—but it could be a much simpler comparison or association. A is bigger than B; X plus Y evokes nostalgic sadness.

This juxtaposition can be arranged sequentially or in an array. (An underappreciated aspect of comics is the reader’s ability to apprehend a page or spread all at once.) It can feature one clear reading path or multiple possible ones. I’d argue that it doesn’t even need to involve more than one image. We associate single-panel cartoons with comics for reasons beyond style or historical association. Comics’ mechanic of juxtaposition operates not just between images but between images and words as well. Even between one part of an image and another! (Again I’m going broad, but broad definitions let more work in.)

Most readers will intuitively understand other elements of comics grammar, whether or not they consciously recognize it. Panels, gutters, word balloons, captions, codes of iconicity that we call “cartooning,” drawing schema like vanishing points that convey space, motion lines, fonts that suggest various sound effects—we see these things and we understand them. We read them. None of these individual elements is needed to make a comic, just like no particular grammatical construction is required in every sentence.

That’s comics—a form built from visual language, with juxtaposition as its foundational strategy. And I want to linger on this idea of juxtaposition just a little bit longer, because in an important sense, it’s also the foundation of poetry. One stress or foot to another, one word to another, one line to another—some paratactic order underlies all poetry, where we hold a thing in the mind, turn to another, hold it alongside the first. Something bounces between them. They complement each other, or contradict each other, or reinforce each other or change each other. They resonate. And since we’re talking about a hybrid form, it’s worth saying that this is how successful hybridization works, too, in terms of its constituent parts. Really it’s the foundation of human thought. We know by comparing, I and thou.

So, comics poetry. It asks, what else can comics do?

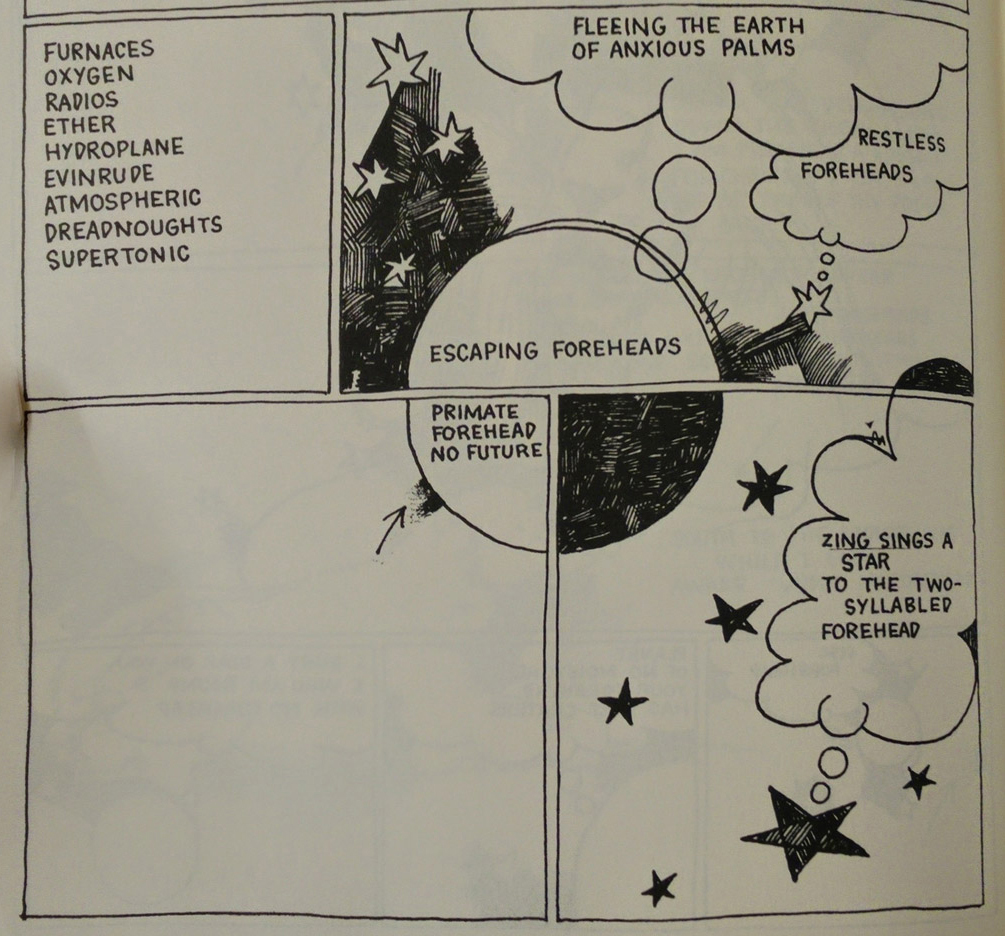

What untapped expressive power hides among those myriad elements of the comics page/spread/book/scroll? Joe Brainard writes out Barbara Guest’s words, “Zing sings a star…” and puts them in a thought balloon, the tail pointing to the moon. How does “sing” change placed inside a thought balloon (or a cloud)?

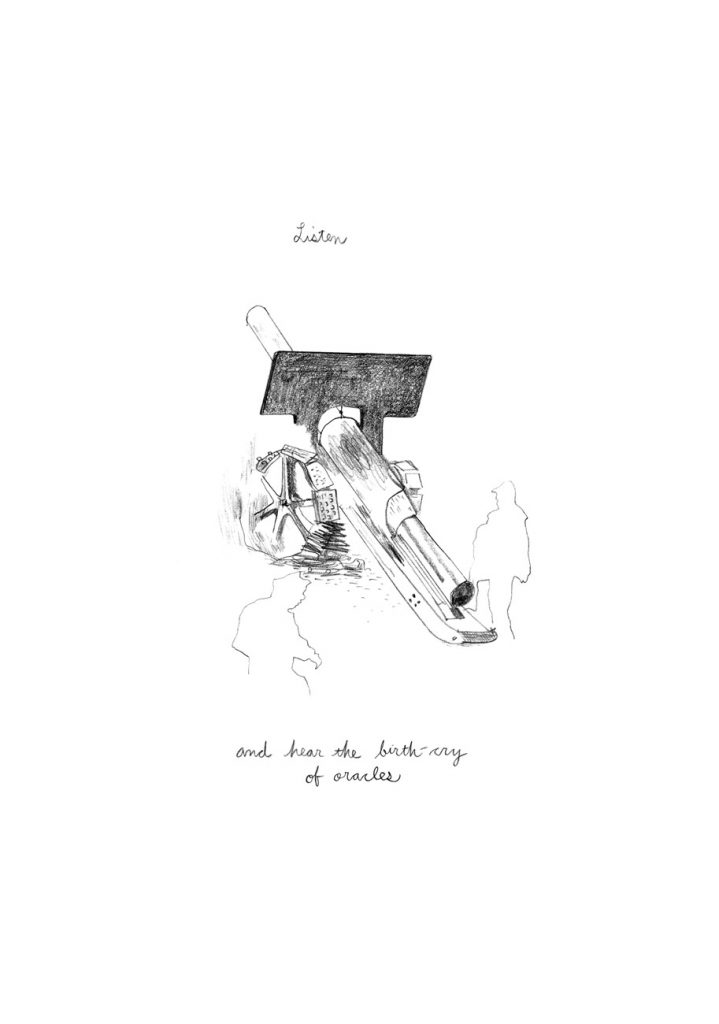

Warren Craghead writes the word “listen” hovering in cursive above a drawing of a WWI cannon, its operators drawn in ghostly pencil outlining white silhouettes. What does this sound like? Can we place ourselves on the timeline of the gun being loaded, fired, reloaded? Why?

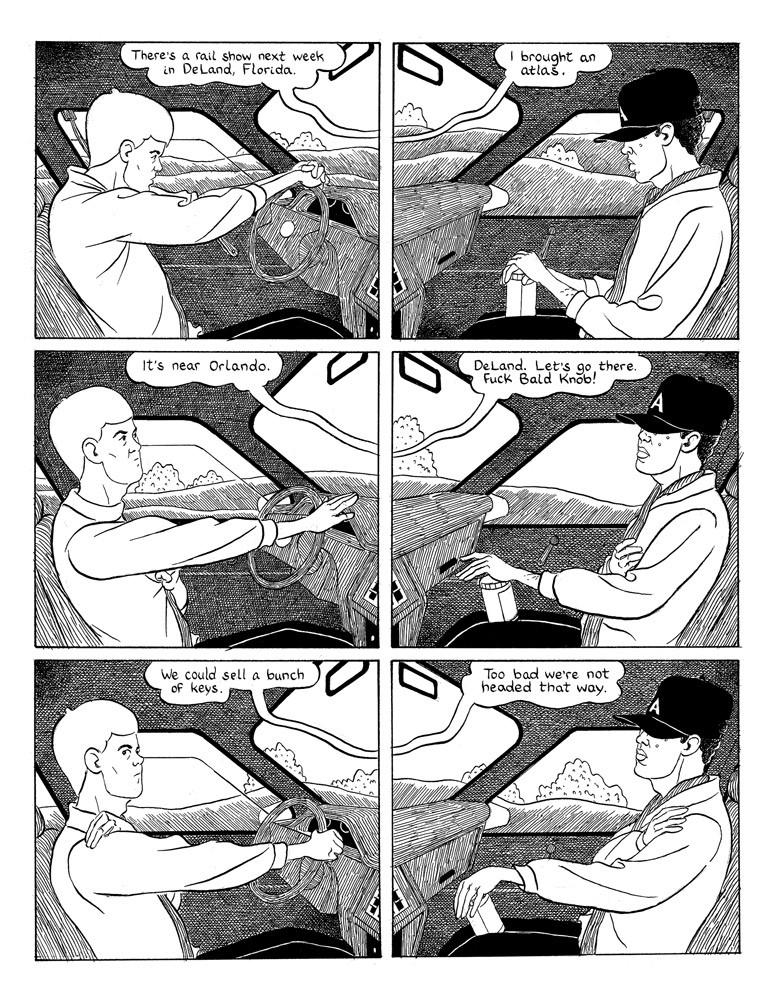

John Hankiewicz draws a conversation in a car. He repeats the same basic structure over and over, flattening and splaying the interior to give us roughly the point of view of either character for any given panel. The word balloons stretch to the unseen character out of frame. What are the effects of these choices and their repetition?

Marion Fayolle depicts a male figure approaching the frame of a mirror. He and his reflection approach each other, bend toward each other, touch. A female figure joins the dance, bends to lift a stone, shatters the mirror and the first figure in one throw. Other female figures join her; they pick up the pieces and reassemble them as collages, reframed in a setting suggesting a gallery. How do we experience time and motion here? What do these visual choices suggest about conceptions of self, erotic desire, gender constructions, possibilities of expression?

What are the expressive differences between black-and-white and full color, or among various limited palettes? Among various strategies of mark-making, or the use of various media? Why might we still describe an evocative image verbally when we could draw it, or vice versa? What difference does it make how something is lettering? Or how text is distributed across the field of the page? What changes when text appears in a caption or a balloon, or simply floats free on the page? And speaking of word balloons, what if the tail points to the speaker in one panel, and a potted plant in the next? What can we get from the strategic deployment of a visual motif throughout a work?

I’m not trying to answer these questions here, but to help generate the work that will. In outlining such broad definitions of “comics” and “poetry,” I hope to maintain as much expressive openness for the form as possible. This work does not call for a particular kind of content. Comics poetry is not synonymous with “beautiful, meaningful comics” or “self-important comics” or “very thinky comics.” It is work that draws upon the expressive potential of visual language.

But ok, fine, you got me. At least one prescription:

Let’s say you decide to make a comic interpreting a famous poem—“so much depends / upon // a red wheel / barrow…” Why on earth would you arrange those words in a panel alongside a drawing of a red wheelbarrow? If a poem is a whole, living work, I can’t see why it needs embellishment. This is nothing against illustration—successful illustration goes well beyond literalist reproduction. Let’s just call this ’stration. Comics poetry should balance freight between image and words. These elements are only doing work if they’re changing each other. Duplication is deadweight.

I want to close with some thoughts about openness and discipline. My position invites some very basic criticisms. If comics don’t need words and they don’t need multiple panels, isn’t every painting a comic? Doesn’t that definition of poetry amount to “good writing”? Fair enough, but I’m sticking with those definitions. All I’m saying is that there’s work to be done (always) and here’s what some of it could be.

But I do think it’s vital not to duck criticism or rigor. Negative capability is not the artist’s get-out-of-scrutiny free card. There’s real value in work that is only intelligible to the person who makes it. But published work is by definition created for an audience, and so takes place in social, contested space.

So how do we thread the needle of seeking both openness and rigor? First, I would say that when I talk about openness, I mean something different than “anything goes.” When I think about this form, I do so as a practitioner, first and foremost. I am after ideas that are generative, not restrictive, of work.

And that’s the thing about schools of art, theoretical frameworks, and definitions: they’re wonderful as long as they’re generative. But these same things are hateful and pointless in the service of gatekeepers. Their job is to be bookmarks, to pull our attention to and through particular ideas. Our job as creators is to make work. I never really care whether a given thing “counts” as comics poetry, because in any case it could be the first push into new territory. And hybrids and liminal things are always more interesting than those that cleave to orthodoxy.

Art is an empathy engine. It’s a practice that establishes a certain relationship with the world. The more one engages art—as either maker or viewer—the more one inhabits different perspectives and subjectivities. (One of my favorite definitions of poetry, quite distinct from the one I use above, is that a poem is a map to a poet’s thinking.) This expansion of subjectivity is how we bridge the distances between people. It doesn’t mean that all art needs to be nice, positive, or politically correct—far from it. But subjective bridging is, in my opinion, what art is for.

This approach to art is both simple and exceptionally difficult. It takes repetition and time. It requires an attitude of receptivity, believing that work—that another person’s subjectivity—always has something important to say. It requires the patience to puzzle out the signal from the noise, to slow down and listen. And if there is any reason that this historical moment might call for comics poetry, I think we’ve found it here.

As a new form (or at least one where precedents are rarely accessible), comics poetry is difficult and uncharted. Practitioners must figure out what they’re doing. And more fundamentally than with most work, audiences must figure out how to read it. Our media environment encourages quick consumption of content that is increasingly custom tailored. This work, on the other hand, asks us to walk a mile or two in someone else’s brain.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply