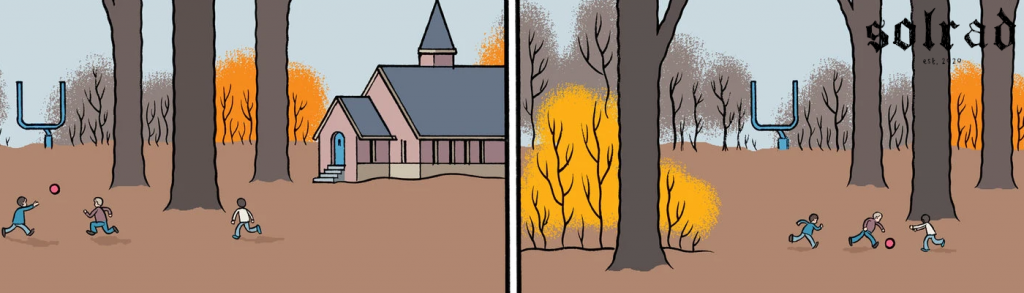

The ongoing saga of Chris Ware’s Rusty Brown is well-recorded at this juncture; Ware is a popular and celebrated cartoonist, and his latest book is the subject of many reviews and retrospectives. Briefly, and as an introduction to this week’s series of reviews: Rusty Brown, much like Building Stories before it, is less of a “graphic novel” than it is a collection of interconnected short stories. These comics have been published over the last two decades in Chris Ware’s personal anthology Acme Novelty Library, and Rusty Brown is a promised first half of a two-part work, published in 2019 by Pantheon Books. Initially set at a parochial school in Omaha Nebraska, Ware introduces a small cast of characters, and then spirals the story outward from them all. Ware has a lot to say about despair and hope in the minutiae of ordinary life, much of which we will attend to over this week’s book club feature.

But I want to talk about making art.

Ware is rather outspoken about making art. He’s had a lot of interviews about the subject, and conversations with other comics luminaries, including Art Spiegelman. His gigantic Monograph, published in 2017, is very much a book about Ware’s views on making art. But you needn’t read any of these interviews, or Ware’s own Monograph, because you can, instead, read Rusty Brown. Two of the major characters (and one of the minor ones) are artists, and the way Chris Ware writes these characters and their lives is an essential vision of Ware as an artist.

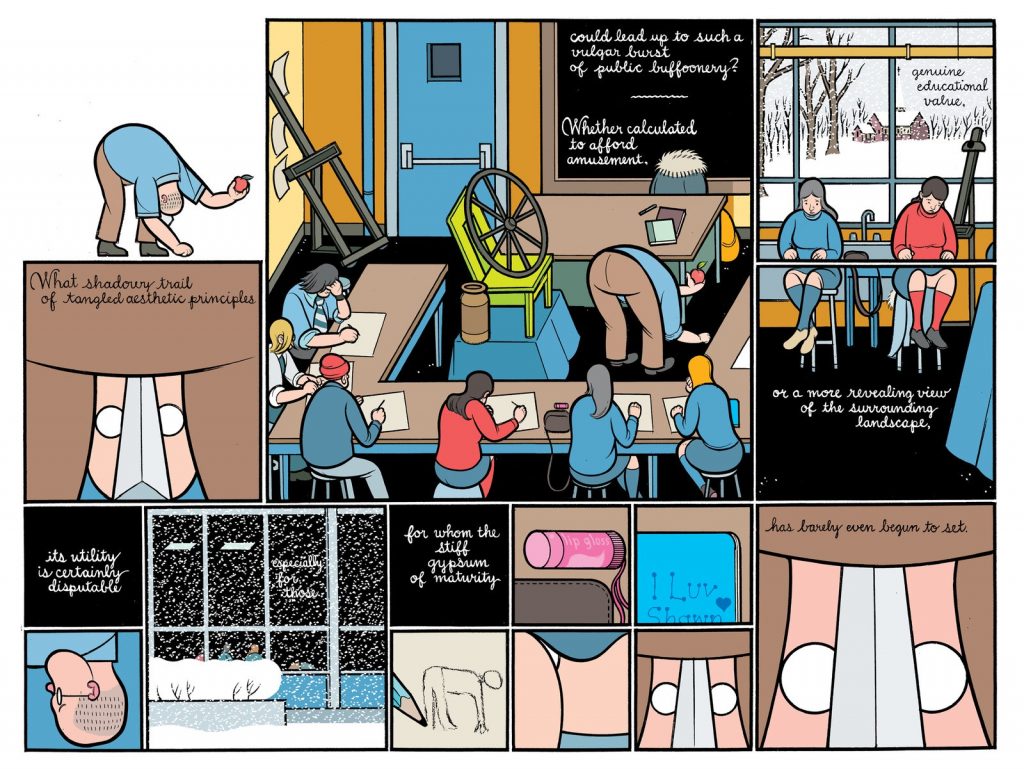

The first artist we’re introduced to is one of the minor characters of Rusty Brown, and it’s strangely, “Chris Ware.” The “Chris Ware” in Rusty Brown is a lecherous painter making absurd poses in his art class to look up the skirts of the high school girls he teaches. He smokes weed he buys from his students and makes pastiche Roy Lichtenstein paintings. The “Chris Ware” of Rusty Brown is an overwrought, laughable, even pitiable mess. He’s toxic emotional baggage, crying and swearing on the phone. He’s a joke – but not the kind of joke the reader is expecting. “Chris Ware” isn’t a self-skewering image of the author on the page. The character is Ware hiding behind his own visage to make fun of self-aggrandizing, high-minded artistes. “How can anything go wrong when you’re the star?” he asks at one point. But seeing the character exist in space, and seeing how laughable and foolish he is, it’s clear that this self-aggrandized behavior is the answer to his own question.

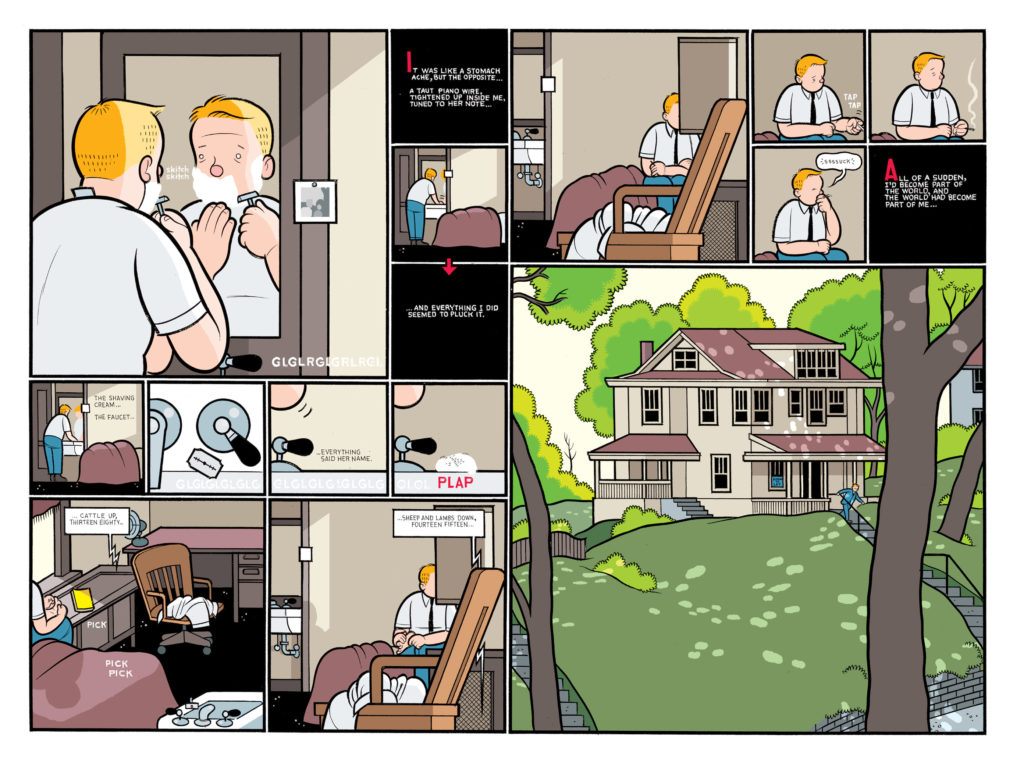

The second artist that the reader comes across has been hiding in plain sight from the beginning of the book; after the first chapter of Rusty Brown, we jump into 30+ pages of a horrifying Mars colonization story from W.K. Brown. This is the very same Woody Brown, father of Rusty Brown, that contemplates leaving his wife and committing suicide in the first chapter. It’s here where Ware starts to jump back and forth in time and shows us the genesis of Woody’s only piece of fiction, “The Seeing Eye Dogs of Mars.” Obsessed with science fiction, Woody Brown graduates college and begins working at a newspaper. He begins to see a woman who works at the paper, but it’s clearly a toxic relationship that gets worse the longer it lasts. With his life in shambles, Woody writes “The Seeing Eye Dogs of Mars.” in a state of fury. The story is a recapitulation of his toxic relationship. Throughout the chapter, Ware shows Woody Brown using this story as a sort of release, a sexual revenge fantasy. After he’s written this single piece, he vaguely thinks about writing more stories, but he’s more concerned with the idea that his former lover might see his work. Ware leads us through the anger and the brokenness of Woody Brown to critique his form of art-making. There’s no durability to it; it is self-defeating and masturbatory. Woody Brown, unlike “Chris Ware,” is a little more relatable, and it is easy to see how he got his broken edges — but he’s still a horrible person.

If we read in-between the lines here, Ware seems to be making the argument that making art isn’t about being self-righteous or high-minded. The “Chris Ware ” character is a wretch, the butt of a joke. He’s not worth spending time on. Likewise, art is not an act that can be spent like a dollar — Woody Brown shows us that at the end of that road there is only anger and brokenness. Intuitively, then, what Ware believes about art-making must be the opposite of these things; art-making is an act of humility and of sustained effort.

So, if you’re looking for the real Chris Ware in Rusty Brown, or at least, the artist that Chris Ware wants the reader to believe that he is, you need to look at his character Joanne Cole.

Joanne Cole is a teacher and administrator at the parochial school in Rusty Brown, and opens the book as Rusty Brown’s third-grade teacher. She’s one of the few black employees at a predominantly white school, and, throughout the story of her life, she deals with micro-aggressions, racism, and bigotted anger from her co-workers and students. She gets paid less than other teachers in the school, gets shifted out of her class to be an administrator when she would prefer to be a teacher, and she takes care of her ailing mother alone, even when her mother still harangues her and prefers her absentee sister. Her stubborn but polite refusal to entertain co-worker George’s gentle romantic interest borders on self-sacrificing.

Important to this focused reading of the art-makers in Rusty Brown is Joanne’s after-work hobby. Joanne takes up the banjo and specifically learns a style of banjo that was popularized by Vess Ossman and Fred Van Eps, much different than the Scruggs-style banjo that is more commonly heard in folk music. It’s a very obscure reference, one that I think Ware makes on purpose. Banjo music isn’t popular, and classic banjo, even less so. Talented adherents to the form are few and far between. The music most commonly associated with classic banjo, ragtime, is rarely played publicly, overshadowed by other musical forms. In the same way, Ware’s particular art form, cartooning, is “obscure” in the sense that cartooning is far overshadowed by music, film, and literature, and that comics that don’t hew to genre conventions are even less common.

Joanne’s artistic practice is very similar to that of a cartoonist. Like a cartoonist, Joanne’s work is mostly done in solitude, the hours of practice and hard work leading to concerts that very few people attend. She composes music, which she later records and plays by herself, mirroring the repetition of the layers of cartooning — pencils, inks, and colors. Music composition, much like cartooning, is an art where the creator of the work relinquishes some kinds of control but retains others. How a reader interprets a comic, or a musician interprets a score, is unique, individual, and part of the magic of the art form. However, Ware argues that comics are much like certain kinds of music; that a superior composer (or cartoonist) can lead any reader to a powerful interpretation, given the composition is of appropriate quality.

Interestingly, at a recital shown in the latter part of her chapter, Joanne presents to only one person, “Chris Ware,” who has mostly been absent from the book since his introduction in the beginning. It’s fascinating to me that at this moment, Joanne doesn’t cancel or reschedule — she just plays — and she plays to a very anxious and distraught looking “Chris Ware.” It’s in this unassuming scene that Ware bares his teeth. “Chris Ware” is a blowhard, and he knows it — Joanne, sheepishly, through her banjo and her hours of labor, puts him in his place. She shows him what art really looks like.

Perhaps because of the strong link between cartooning and the music that Joanne Cole plays, it’s no surprise to me that Joanne is the only character in the book that gets a redemptive or hopeful arc. It’s not that her art has brought her some notoriety, or has anything to do with this emotional closure — far from it. But Joanne is the only person in Rusty Brown who has put in the work, day after day, year after year. The other artists around her are disappointments, fools, or flashes-in-the-pan. But Joanne keeps plugging away, just like Ware keeps plugging away.

As a comics narrative, Rusty Brown often feels stuffed to the gills. It’s a claustrophobic kind of comic. But this isn’t a bug; it’s a feature of Ware’s own vision of what comics should do. Throughout the thousands of panels and twisting layouts, Chris Ware composes a symphony of a comic in Rusty Brown. And, importantly, it works; the comic is clearly a masterwork, a powerful exemplar of the comics form. In Rusty Brown’s composition and in the humility and dedication of its most sympathetic character, Ware reveals to readers a vision of art-making that is powerful, simple, and difficult to adhere to. Everything else is superfluous. What matters is the work.

READ MORE FROM RUSTY BROWN WEEK

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply