By way of full disclosure, I’ll preface this with an admission: I’ve had a love/hate relationship with Chris Ware’s work over the years. On the “love” side of the ledger, I’ve found his innovative page designs and layouts fascinating in the extreme, and his story structures a thing of wonder to parse and puzzle over. His coloring choices have always appealed to me, as have his stylistic callbacks to adverts and publications of days gone by. His skill as a cartoonist is, to my mind, beyond debate, as set in stone as any of the Ten Commandments or the amendments in the Bill of Rights.

The latter may be looking a bit shaky right now, I’ll grant you, but Ware’s stature within the this medium we love surely isn’t — the late-2019 release of his long-awaited new book from Pantheon, Rusty Brown, was arguably the comics publishing event of the year, and it has garnered much attention and discussion both within the loosely-defined “comics community” and, crucially, without, cementing the idea that he’s at the very least a reasonably-well-known cultural figure who is producing an important body of work worthy of study, analysis, and, more frequently than not, celebration. A serious artist for serious times.

I’m in no position — and frankly don’t even have any desire — to argue with any of that, BUT (and you probably guessed this was coming from the outset) there’s always been something at the core of Ware’s work that’s missed the mark with me. Socially and physically alienated white guys aren’t a bad thing to read about on occasion, but his inability or refusal to move beyond his own demographic comfort zone has been a source of frustration for at least this critic, and the cumulative effect of years and decades of his comics has been one of “variations on a theme” more than a series of discrete, “stand-alone” efforts, more comparable to the creative ouevre of a Woody Allen than, say, a Paul Thomas Anderson.

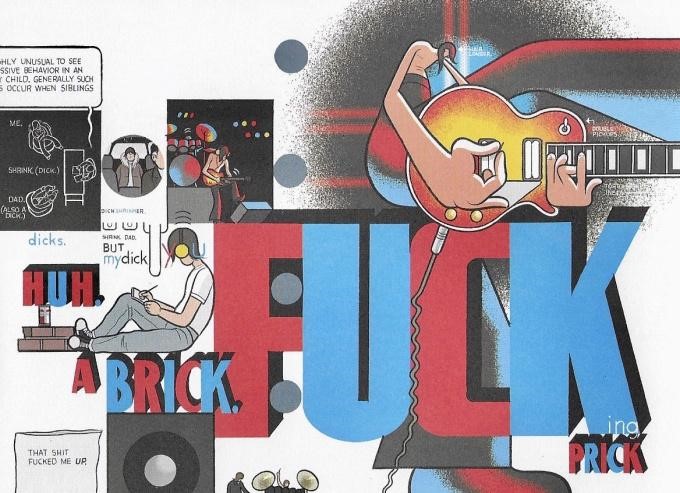

I again have to give Ware some credit, though: the source or, in comics parlance, “origin stories” of his various characters’ sense of displacement, and their inability to articulate their own ennui and/or pain, has always been one of his primary motivations as an artist. No one in Ware’s comics arrives on the page fully formed with no backstory — peeling away the layers of their own personal onions has always been his specialty. He hasn’t always been consistent in where he points the finger of responsibility for the quietly tragic predicaments his protagonists find themselves in — with Jimmy Corrigan he laid it firmly at the doorstep of a tragic childhood by way of dissembled and vaguely mysterious memories, while the ensemble in Building Stories are, more often than not, victims of uncaring circumstance — but that seems fairly realistic to me, the nature versus nurture debate being a constant in many of the sciences, social and otherwise. What I find interesting about Rusty Brown, though, is that he seems to be considering the nuances of both points of view within the same work and arriving at no hard and fast determination as to how people end up in the fixes they’re in — and he also seems open to the possibility that some may simply be following an inherently flawed inner nature. I don’t mean to imply that he’s gone “full Arthur Janov” or anything, but at least some of the various and sundry personages in this latest book seem almost pre-determined to end up the way they end up, and at least a couple of them strike me as being the sort who might benefit from some rigorous “Primal Scream”-style therapy.

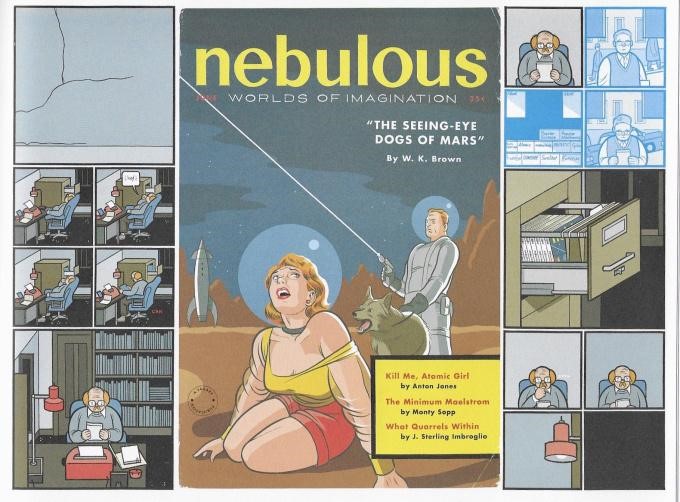

Atop that list is probably our title character’s father, school teacher Woody Brown. A self-absorbed jerk of a man wrapped up in fantasies of a life that could have been — and at least one that couldn’t have been — Woody is a frustrated would-be science fiction author who takes a pulp-esque flight of fancy to Mars in one of the book’s most daring and revelatory sequences (a marked change of pace from the rest of the proceedings, which are loosely structured to resemble an old school prime-time television line-up). Woody seems to be following, largely unwillingly, a kind of pre-set course with his existence. In Woody’s case, especially, the intractable edifice of his life has been solidified by a series of poor decisions that he seems to know he shouldn’t either have made or still be making, but what are ya gonna do? Powerlessness is a comfortable, if soul-deadly, trap, and I’m curious to see how completely his son, Rusty, falls into it. Early indications would seem to answer that with “pretty completely,” but so far Ware has afforded him less “screen time” than any other character, including Ware himself, who appears throughout in the guise of a self-deprecating caricature drawn in far broader strokes (metaphorically) than the rest of the cast.

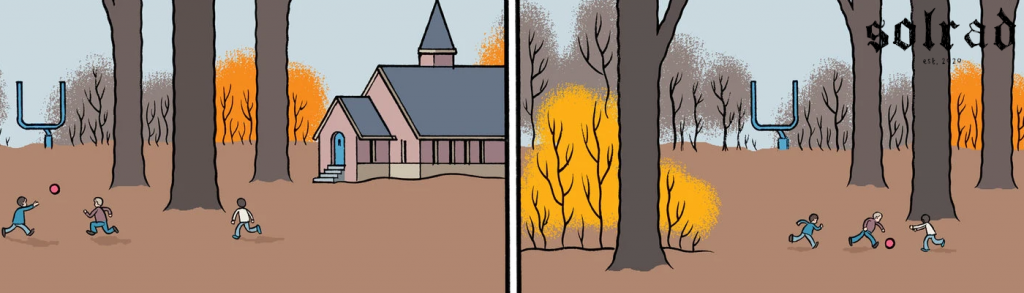

Siblings Chalky and Alice White — the pair of whom would appear to serve the roles of constant victim of and consistent foil (in any number of respects) to Rusty — likewise seem to have their futures unconsciously (or perhaps even subconsciously) mapped out for them from early on in their lives, although the two of them are likely to be fleshed out more considerably in the next volume. The “sample size” for each may be a little bit smaller, but the general contours of their roles in this story are reasonably well-laid out — as are the pages they appear on — but that’s to be expected at this point, as Ware’s near-architectural eye for design and composition never fails to disappoint, even for those of us not as “into” his work as, it would appear, the rest of the world is.

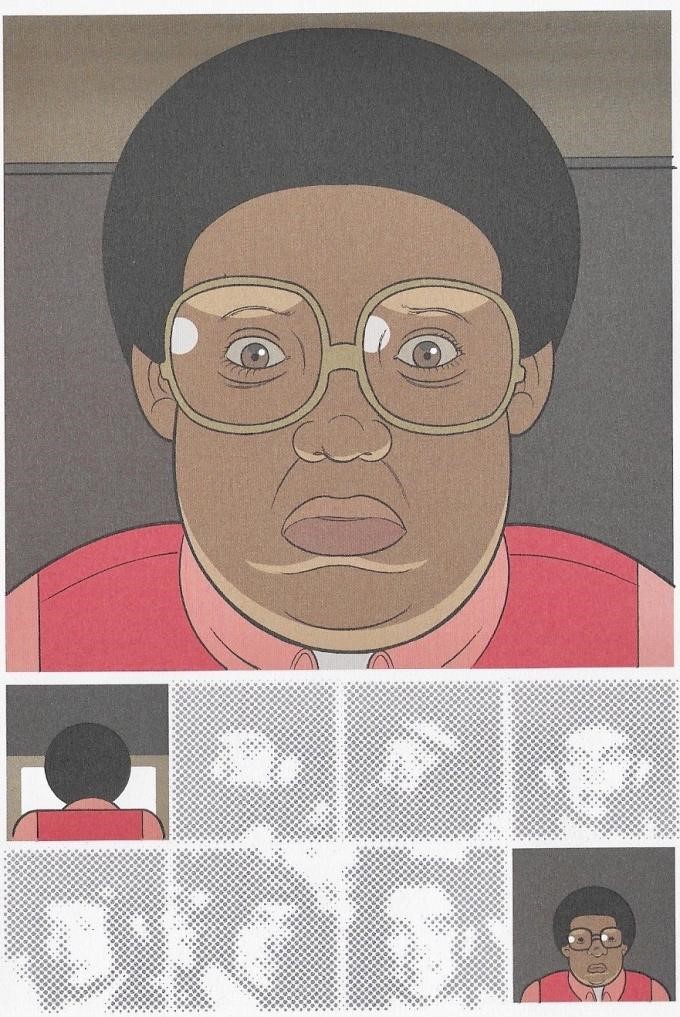

Representing the other side of the developmental divide, however, we have noxious bully Jordan Lint and school administrator Joanna Cole. Ware, by no means, ever goes so far as to actively feel sorry for Lint, but he does play a bit of “Sympathy Of The Devil” by showing him to be someone whose potential was disastrously re-routed thanks to a lousy upbringing, and he reserves genuine sympathy for Cole, perhaps the most tragic figure of the bunch, who has spent a majority of her life dealing with the effects of racism in both its explicit and implicit forms, causing a kind of Jimmy Corrigan-esque “withdrawal in plain sight” to take root within her. The pain she carries within her is deep and conveyed with an admirable degree of authenticity, and her self-imposed “Exile On Main St.” is perhaps a more generous reaction that the shit world around her deserves.

In the final analysis, then, it’s this sense of ambiguity — of Ware being less zealous in his beliefs as to the origins of everything ranging from personality characteristics to existential angst — that had me more invested and interested in Rusty Brown than I was in his prior efforts. This has me looking forward to its follow-up more than I probably would have expected to be. His formal skills are as strong as ever, but they resonate more than ever now that they’re matched with a more philosophically balanced approach to storytelling. In years past, Ware seemed to be constructing his work in order to amplify the core conceits and ideas behind them, whereas in Rusty Brown he appears to be letting his characters tell their own stories and arriving at multiple viewpoints for readers to consider . It’s as harrowing and downbeat as anything he’s ever produced, but it’s a heck of a lot — dare I say it — more exciting and less didactic. He doesn’t have all the answers anymore, and that makes for a far more challenging and absorbing reading experience.

READ MORE FROM RUSTY BROWN WEEK

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply