Rusty Brown, Chris Ware’s latest graphic novel, is the proverbial major work. It’s also an infernal narrative engine and veritable test, one I’m not sure that I passed.

For the last twenty-odd years, no American artist has been more dedicated than Ware to expanding the scope of things that comics can notice, or so interested in what it means to take notice in the first place. The pleasure of reading Ware has to do with the way he captures experiences that, at one time, almost no one believed comics could capture. Time dilates in Ware, and we sense ourselves sensing things: a snowflake, an itch, the clicking of doors opening or closing. On that score, Rusty Brown is a fund of minute observations and tiny, stabbing poignancies: an anthology of masterful effects. Yet Ware’s stubborn, almost vindictive return to certain thematic foci, his pitiless naturalism, and, above all, the helplessness that clings to his characters—the way sodden clothes cling to you after you’ve accidentally slipped into a pool—all that, I have to say, makes Rusty Brown a trial. It may be the quintessential Ware book, but I do not love it.

By now it’s a cliche to observe that Ware hates fun or engages in a relentless “miserablism,” that his work amounts to a hard slog through a kind of willed wretchedness. I have never wanted to add to that vein (by now a distinct genre) of Ware criticism, one that I hear particularly among self-styled populists, primed to celebrate the putative mainstream of comics and averse to Ware’s sad, psychologically fraught storytelling. If Ware is awe-inspiring to some, he is an affront to others. I’ve tended to defend Ware because of the terrible poignancy his work can achieve, and its exacting depictions of human interiority. He has boosted the range of what comics can evoke. The awful, knowing depiction of deluded white masculinity in Jimmy Corrigan, the piercing depiction of the joys and terrors of parenthood in Building Stories—these are things that matter. We could explain these partly by literary analogy: the Proustian drift of memory and words, the Joycean drive to render inward states by testing the limits of his chosen form (Ware often cites Joyce in his interviews). Since I once staked my writing career on the idea that comics could be literary, that kind of comparison should be in my zone. But I may have reached an endpoint with Rusty Brown, past which I have a hard time imagining reading Ware’s work with joy. Maybe I have come around at last to those cliches about hating fun.

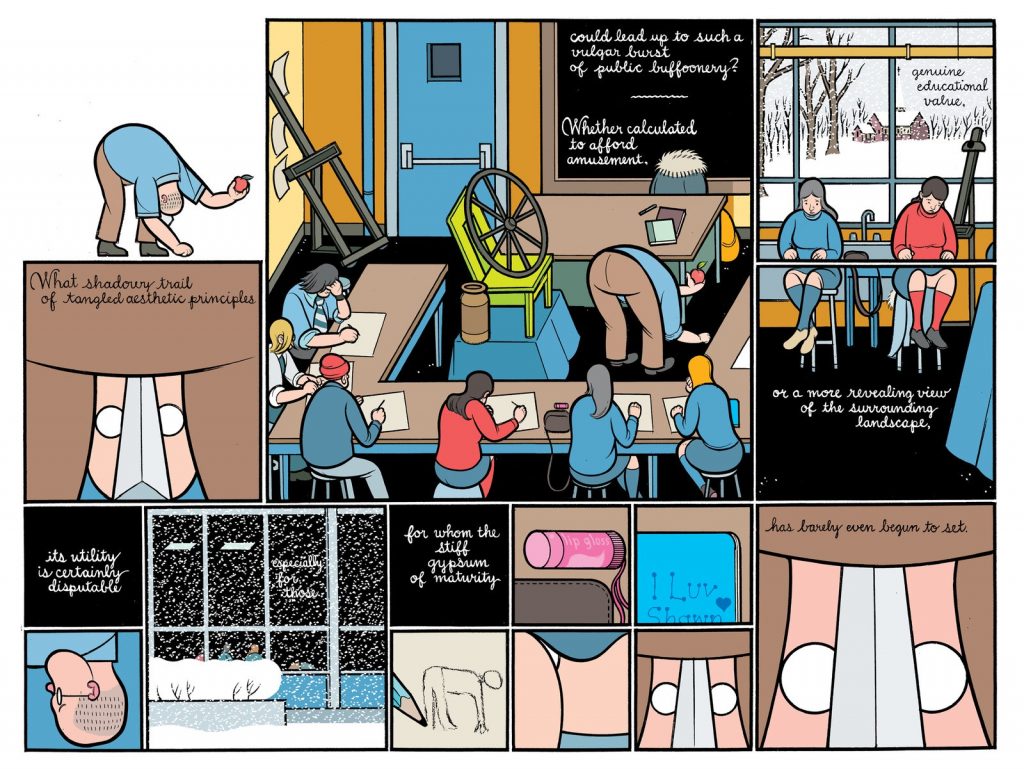

Rusty Brown devotes much attention to the self-deluding fantasies of socially isolated, pitiable yet toxically self-involved boys and men: in sum, male geeks. These include grade-school uber-nerds Rusty Brown and his tentative new friend Chalky White (whose very names call to mind bullying joke names like I.P. Freely and Rusty Bedspring), as well as Rusty’s father “Woody” Brown, a fumbling school teacher at a desperate crossroads in life whom almost everyone treats with pity or contempt. Rusty and Chalky engage the little world of school through protective heroic fantasies, recalling the pathetic Superman figures of earlier Ware stories, and bond secretively over a Supergirl doll (action figure?). Supergirl is Rusty’s toy, and becomes the focus of his nascent sexual fantasies (he is puzzled by his own hard-on) as well as his superheroic self-image. She is the eroticized token literally passed back and forth between Rusty and Chalky, a play piece that (in Eve Sedgwick fashion) cements their budding homosocial relationship. They perseverate around this doll, though they are terrified that their classmates might discover it. Ware obviously understands how the Romantic fantasies of young boys as rescuers, or escort heroes, may be shaped by sexism and obsessive cathexis. Meanwhile, Woody’s chunk of the novel recounts his failed career as a pulp-era SF writer as well as his subsequent choked-off life. The schoolboy fantasies of Rusty metastasize into Woody’s creepy ogling of high school girls. Again, desperate. To sharpen this critique even further, Ware casts a damning version of himself, a fatuous art teacher named “Mr. Ware,” as another nerdy creep eager to steal upskirt glimpses of the girls in his class. Mr. Ware, a grownup geek, ironically sneaks out of school to get high with metalhead stoners who openly mock Mr. Brown and love to bully and torment the schoolyard nerds. It’s all ugly, though the bullying and quiet anguish do ring true.

What gets me is that none of the nerd fantasies depicted in Rusty Brown seem to provide resources for self-fashioning, or ways for the put-upon nerds to make up cool stories, build meaningful relationships, cherish a love of craft, or find emotional refuge in anything other than the meanest terms. Though Ware reserves special contempt for the bullies, the young nerds too are pitiful, dispirited, and fundamentally small: objects of pathos, never of admiration for their abilities to cope and imagine things, to cobble together their own stories from whatever junk mass culture gives them. Their imaginings are deeply sad. Ware’s dramatic argument here is loaded, and reinforces a now-familiar sense of helplessness before incomprehensible social demands: an echo of literary naturalism, but with a crypto-autobiographical, geek-culture twist. The novel seems to dissect Ware’s own boyhood yearnings through the lens of a trope he often revisits, the superhero: while Rusty dreams of heroism, would-be artiste Mr. Ware uses superheroic images ironically for the sake of his derivative, pompously defended Pop art (a sure sign that the real Ware holds Mr. Ware in contempt). At the same time, the novel damns just about every other form of masculinity on view. Reading Rusty Brown, then, is an exercise in seeking poignance while taking a bath in sustained self-loathing, surpassing even the depiction of the traumas of the Corrigan men in Jimmy Corrigan. It is, for me, a damnably hard slog, even when punctuated by astonishing formal conceits.

It seems to me that the cast of nerds in Rusty Brown — or the psychomachia enacted by the aggregate soul that is Rusty, Chalky, Woody, and Mr. Ware — constitutes a brutal, embarrassed rejection of a geekdom that warrants more shaded, generous treatment. Alas, the novel is unremitting, its nerds are miniature monsters, and all its key players helpless and alone, lacking agency, even the questionable sense of agency that might come with the self-serving heroic fantasies of youth. This self-loathing vibe never lets up, and Ware’s naturalism often clashes with satirically overwritten passages of deluded comic book-speak, deluded art-speak, and so on, dead stretches of gaseous, unrepeatable prose.

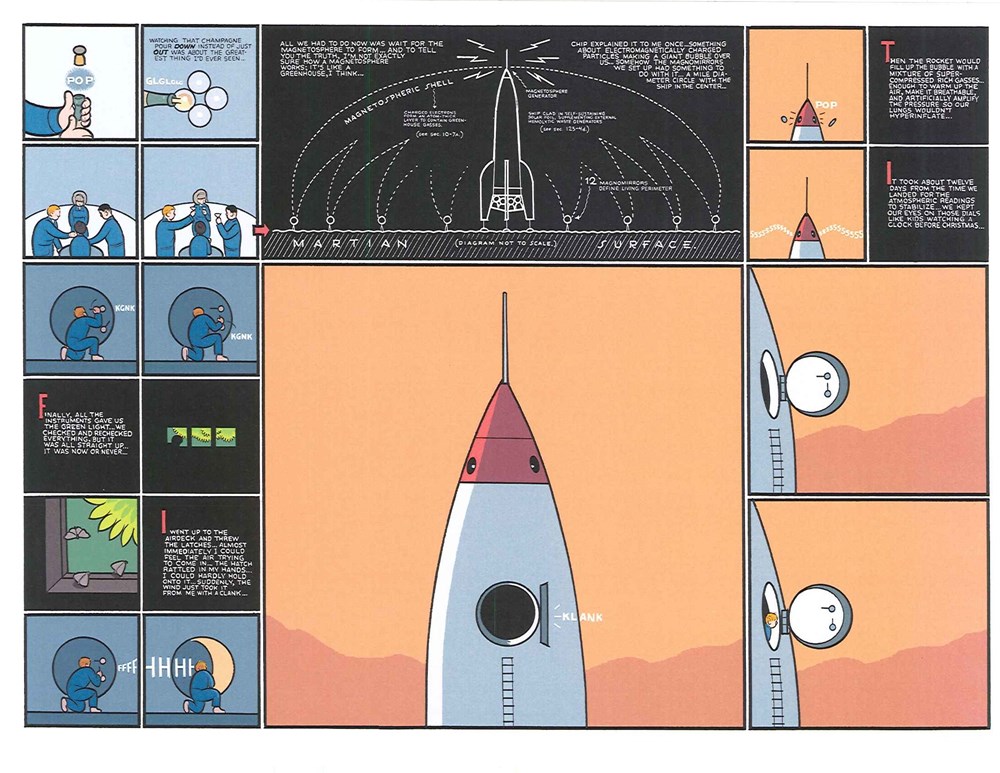

Even some of the best things in Rusty Brown feel rigged. Take “The Seeing-Eye Dogs of Mars,” a knowing pastiche of late-fifties era pulp science fiction first published in Ware’s Acme Novelty Library #19 (2008). This story within the story is supposed to have been written by Woody Brown, in his one real accomplishment as a professional writer. “Seeing-Eye Dogs,” presented as part of an imaginary pulp called nebulous, is a fair knockoff of a psychologically tense space colonization story from the late John W. Campbell/H.L. Gold era of magazine SF. Actually, it’s a psychological horror story in which the decidedly unreliable narrator, a chivalrous, gung-ho rocket pilot and Mars colonist, turns out to be a blandly sociopathic rapist and killer (do read Casey Nowak’s brilliant take). The story ends tragically, the narrator stuck in his lone Martian outpost, seemingly having lost his mind and all his companions. By then he has become such a hateful figure that one can only long for him to wink out like a spent candle. Ware did his homework here, capturing in this disturbing tale many of the hallmarks of fifties SF, and the story is taut, its logic inexorable, like a trap closing in slow motion. As we near the end, further revelations about the narrator’s actions lend a terrible chill. It’s a smart, insinuating pastiche, one of Ware’s best writerly efforts at ventriloquizing (much more convincing than his superhero parodies). One might imagine that author “W.K. Brown” was deliberately inhabiting the mind of a psychopath, and aware of the misogyny underlying the narrator’s self-characterization as ardent lover and escort hero.

But, no, Ware follows “Seeing-Eye Dogs” with the story of its writing, a story that casts the entirety of pulp SF as a desperate and unconscious sublimation of thwarted sexual impulses, naively vomited up. Author Woody appears as a painfully shy, virginal, Jimmy Corrigan-esque newspaper writer in 1950s Omaha who stumbles through an awkward affair with an office mate, one that opens his life to sex but knocks him for a loop. Woody obsesses over this office mate, spins fantasies of their life together, begins spying on her, and, of course, drives her away with his obsessiveness. There’s a series of rising setups and disappointments, each worse than the last, as Woody cluelessly tries to romance this (to him) indecipherable woman. He loses his job and his apartment due to his obsession, but compensates by bingeing on 1930s-era SF pulps—all lurid, of course, with ripe titles like Salty Planet Stories and Sparkling Spunk (Ware is trying a bit too hard here). This inspires Woody to write “Seeing-Eye Dogs,” a story he later manages to sell, after falling into a loveless marriage with another woman that sets the pattern of his life to come. In short, Woody transforms from a pitiable, socially anxious nerd with romantic fantasies into a curdled misogynist whose dreams are broken. “Seeing-Eye Dogs” is his monument: an expression of confused sexual rage. Here, Ware lapses from a carefully researched sense of period and genre into an ugly, overdetermined caricature that is likely simply to confirm the usual high-minded literary prejudices against SF.

In fact, a reactionary judgement of the value (or valuelessness) of such genre fiction informs much of the novel, as it does a good chunk of Ware’s oeuvre. As a result, “Seeing-Eye Dogs,” one of the best things in the book, sadly ends up flattering rather than challenging the sort of reader for whom SF and fantasy (and comics) have always been a bit suspect. This is rather too easy, and hollow. Rusty Brown, as it walks a tightrope between earned sympathy and retributive harshness, often stumbles.

Oh, but there is some relief. The very best thing in Rusty Brown, and the one thing previously unpublished, is the novel’s last quarter, devoted to teacher and musician Joanne Cole, an African American woman working in an overwhelmingly white school. We see Joanne throughout the novel, but get to know her only in the end. Her story is the book’s freshest and riskiest element, also the easiest to read, and actually ends (or rather pauses) with a scene of human outreach and sympathy that is the more powerful for its contrast to much of what comes before. We see Joanne at various ages, from new young teacher to middle-aged administrator, and follow her complex, largely unspoken relationships and her passion for the banjo. Ware presents banjo music complexly, as both a great tradition that Joanne gets to know and a historic focus of racist stereotyping. No one else seems to understand Joanne’s devotion to the instrument. Throughout, Joanne is diligent, pious, decent, long-suffering, and put upon by racist colleagues, students, and institutions. The stinging disappointments in her life are not unlike those borne by Rusty or Woody Brown, but Joanne is a more sympathetic character, and the affronts she endures suggest a fuller social context, rooted in Ware’s deep knowledge of the racist history of what he knows best, the white American Midwest. To be clear, Joanne isn’t merely a saintly sufferer, and the novel gives her resentments and troubles: human complications that enrich her portrait. She appears severely repressed, or perhaps forcefully gathered-in and self-contained. In fact, she keeps close a secret that comes blurting out in the book’s finale—and here Ware does not cheat, but walks out on a limb as a writer, to strong effect. I felt a weight lift here. I’d be happy not to read anything else about Rusty or Woody Brown, but I want to know more about Joanne and her family. This is the part of the book I am most anxious to read criticism of, and to reread.

Sigh. It occurs to me that whereas I once greeted Ware’s work with an all-embracing love, as confirmation of comics’ expanded range, I now wish for a broader sympathy and some escape from a sensibility that seems poised between shamefaced nostalgia and self-contempt. Of course, it would be premature to judge this volume as a rounded-off statement; Rusty Brown adverts to its incompleteness, and promises a second volume, which will be coming down the road God knows when. Ware, I think, will have more to tell us, and, despite my qualms, I expect to read it. Perhaps the second volume will feel less like a fossil record of nearly two decades’ growth and more like a distillation of Ware’s best. As is, this first half at times feels mired in an outlook that Ware hopefully has outgrown.

Viewed by itself, the book is, of course, formally brilliant, balancing Ware’s preference for organic artistic discovery en route with an overarching architectonic sense of structure. Ware lends the book integrity via a lexicon of braided visual symbols, most obviously the many eye-like devices that suggest a thematic emphasis on seeing and being seen. Further, he excels at synesthetic conceits, notably the rhythmic visual evocation of music (even when, one suspects, the music is far from what he loves: dig his exacting treatment of “Stairway to Heaven”). At times, though, the novel feels downright ungenerous to the eye, and hermetic; I will remember reading it as a tug-of-war between wanting to reach for my magnifying glass and just wanting to get on with it already. It boasts some of the tiniest info-loaded panels I’ve seen, and demands no less than that readers rededicate themselves as they go, page after page. Reading it, then, is properly challenging, indeed a holy grind. But it’s more than formal rigor, cramped panels, and minute text that make it so; it’s the novel’s moral and psychological outlook, its brutal way of caricaturing most of its key players. Rusty Brown, in sum, feels less like an openhanded experiment in delineating lives, and more like an exercise in destroying them. Except for Joanne, the book’s main characters–whether the desperate nerds that dominate its early chapters, or the loathsome bully Jordan Lint, who becomes the target of Ware’s most strenuous formalist gambits–are wretches through and through. By the book’s end, I was grateful to get out of their company and come up for air.

Thanks to Craig Fischer for his input and help with this essay. (I hasten to add that the opinions and judgments are all my own!)

READ MORE FROM RUSTY BROWN WEEK

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply