I’m here in the meta-meta context of this story about Mars and I’m palming a cold surface like the brushed steel body of a nuclear missile. Inside of it is something that broke matter, broke the rules. The real rules, the only rules. I’m aghast at this sensation, and genuinely proud of myself for feeling it and being subsequently aghast. Do you ever find yourself reading things that wash over you, like bath-water? Have you ever seen something violent, and at the same time felt perfectly comfortable? Have you ever enjoyed the competent film-making of Saving Private Ryan while a more sensitive person sat next to you and sobbed wildly at the violence? Me too. How awful.

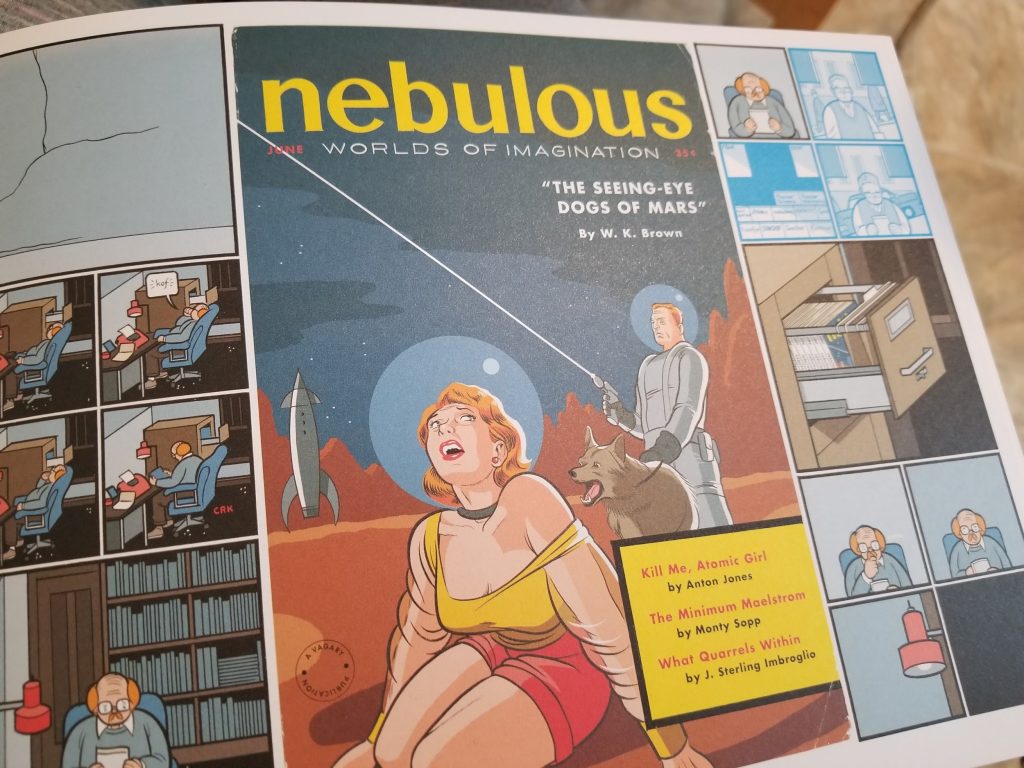

The disgust I felt as I read The Seeing-Eye Dogs of Mars, then, was significant to me. I felt pain for the main character and for each of the poor victims of his confusion. I understood, perhaps for the first time, the kind of fear that drives annihilation. I felt it. I felt its effects. I spend every moment of my own life obsessing over comics and storytelling and the way everything functions and why and I was still basically tricked by Chris Ware into feeling not only sympathy for an idiotic evil-doer with no clear goal but also the hopeless terror of being at the hands of such a person.

Once, at Disney World, I saw a guy in a t-shirt that said USA: TWO-TIME WORLD WAR CHAMPS. Something honest in that — something I think Chis Ware finds himself reflecting on — America’s idea of itself might be based on the pursuit of freedom, but anyone with access to Wikipedia can tell you that’s a naked delusion. What, then, do we fight for? We fight to win.

As I froth at the mouth and fingers, what I really want is to write a full essay on every narrative fulcrum of this story, but I’m required to be brief, and I’m not being paid much. The true (no — maybe just my favorite) center here — that “one” moment, the bright red dot the narrative spins around — comes early. We learn that two white American couples are being sent to colonize Mars — the first human dispatch of many. Why? Because the Russians took the moon, so, and I quote, “where else were we going to go?” I feel the same chill here, reading this line, as I do when billionaires talk about going to space with their billions like it’s the most obvious and correct idea. Why are we going up? Why are we going out? Because we see a horizon. Because the horizon exists.

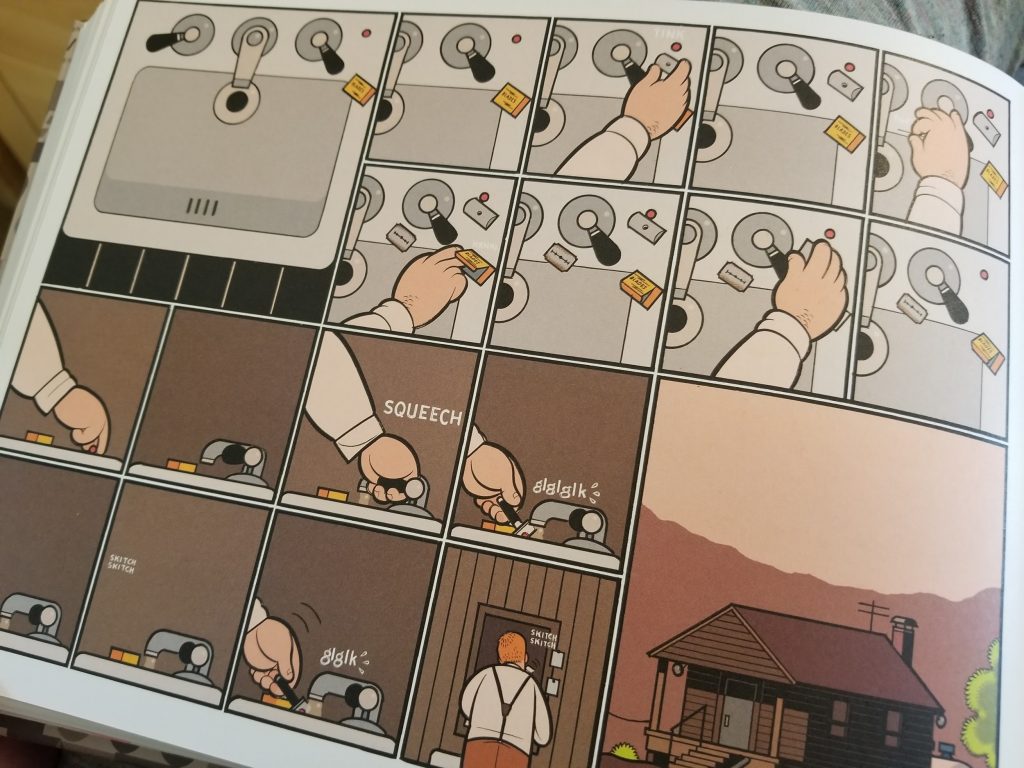

The reader has access to the potato-chip thoughts and memories of our protagonist, Rusty, as he goes about taking care of himself and his plot of land — a scene Ware has stretched out over dozens of panels, impressing a long “silence” upon the reader. The ponderous sequence also gives one the opportunity to be jarred by the presence of retro-futurist technology in the home of someone who, a moment ago, might have been a frontiersman in the old west.

We are given a few flashbacks before Rusty is compelled to reflect on his childhood habit of stalking and mutilating moths in a dark orphanage attic. This is depicted beautifully, the image coming back to juxtapose itself and its meaning again and again. Think of an angry little boy, a kinetic invisible presence needlessly killing moths in a sweltering, cedar-smelling attic. He brings it up mindlessly, innocently, in relation to something that seems completely alien to dark attics, moths, and childhood. The dissonance between Rusty’s triggered memory and the situation at hand is another of those fulcrums — the slippery, tangled chaos between this man’s experience and reaction. Rusty tells us later that he did well in school and in the military — heck, he’s an astronaut, isn’t he? He was sent by America to the edge of human understanding and experience. The people have chosen him to be the very last man in charge, yet his narration is that of a humbly articulate child, whose reflections on the world float in and out of an indecipherable interior.

As The Seeing-Eye Dogs of Mars progresses, things start to go poorly for these two couples who are more or less stranded on Mars, and every event is refracted through or obscured by Rusty’s spooky labyrinth of defensive, primitive thought. He is baffled and hurt as his companions begin to alienate him — his wife seems to have vanished into the pitch of night at one point — but as things progress and Rusty loses more and more control of the situation, his confusion turns into anger. His wife, along with the other couple, attempt to escape to the next settlement — which is miles away, if it exists at all — so it’s already a bold action, and yet still we find out that one of the party is injured, and needs to be carried on a stretcher. To these three people, it is worth risking a freezing, choking death to get away from Rusty, and he just barely pauses to adequately reflect on why that might be. According to his narration, to his memory, they’d all been “getting along fine”. As if his mind is like a series of prisms and traps set to catch his perceptions and feelings and turn them straight into crudely articulated anger and action, protecting him from guilt, shame, or empathy.

It makes me think of the big bang, and evolution, and other cosmic stuff. Mars. I think of this little boy brain coming into the world and having no one around to teach him the purpose of love, but who excels in school and in the military. I think of the absence of his parents being filled by flat, bored nothingness. I think of Rusty slipping into an attic to kill three small, soft, harmless things in the dark for no reason.

Rusty pursues his companions, noticing that they hesitated before passing the perimeter of their habitat, an invisible field beyond which bare flesh will instantly freeze. Rusty starts to run after them. On the most awful page, we see the night-time chase illustrated as a thick dark blue border — 40 panels of Rusty, the ground, the sky, and Rusty’s stomach-churning inner-monologue. Within this border are 8 additional panels, devoid of his commentary and twisted perspective. In broad Martian daylight we see him gently pull the frozen legs off a still-living dog with a sickening “SPLCHK”, all while speaking words of empty comfort to the animal.

The story flares in conclusion, and Rusty’s confident, folksy misconceptions grab onto every proximal living thing and do a final death roll. The end sees him tending to things dead and gone as though they aren’t.

It’s all pretty grim, but I don’t think Chris Ware actually feels that this kind of abrupt and inexplicable violence is inherent to our species or even American culture. Recognizing a truth is different from judging that truth good or bad, and Ware perhaps knows that to do the latter is not a useful or particularly interesting way to think about the human experience anyway. Besides, Ware himself is not taking credit for this story — he puts it in the hands of W.K. Brown, and we are about to be made aware of his many reasons for being a cynical narcissist and for wanting to depict our kind without its skin. In using this hapless parenthetical author character, I feel Ware further revealing to me that he knows horror grows from pain. Horror is what you become when you destroy your own most sensitive parts and consume them in order to survive.

I’ve known a few Rustys — and I suspect Ware’s known plenty himself — persons so completely alienated from their own emotions that all they can do is drive forward in the straightest possible line, willfully ignorant of the harm they do to those in their path. I find them as alluring as they seem to find that point just beyond everyone else’s sight. They want to get there first, and I have an instinctual urge to follow right behind them, because I fear I might otherwise be trampled.

READ MORE FROM RUSTY BROWN WEEK

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply