Chris Ware has two primary impulses in his work. The first is an artist deeply concerned with the possibility and complexity of human connection and our desperate attempts at creating it. The flip side of that sees Ware exploring issues related to abandonment and rejection, as well as the traumatizing effects they both have. Ware’s second impulse is that of a scorched-earth satirist. While much of his venom is aimed at the art world and consumer culture, he saves much of it for himself. Two of his most vicious creations are Rusty Brown and Chalky White, introduced as odious comic-book and pop culture collectors in the pages of his Acme Novelty Library series. They are the sorts who are incapable of experiencing any kind of joy outside of the temporary narcotic (and neurotic) release of acquisition. Ware is clearly skewering his own obsessive tendencies because no one can satirize a subject like an insider.

The Rusty Brown graphic novel, the first half of which was published in 2019, is Ware’s most ambitious comic in part because he’s seeking to understand and empathize with a wide swathe of human experience. That includes bully/victims like Rusty, his dad Woody (a teacher), and frequently repulsive bully Jordan Lint. The unifying concept is a huge, sprawling narrative that extends back and forth in time involving seven people. They are Rusty, Chalky, Chalky’s older sister Alice, Jordan, Woody, Rusty’s teacher Joanne Cole, and “Chris Ware,” a version of the artist who becomes a high school art teacher. They are all connected through a location, an elementary school, and the long introduction that comprises Rusty Brown spins the first strands of their infrequent but decades-long interactions.

Ware digs into these connections by exploring memory and its connection to identity — especially the ways in which it’s fallible. In this volume, he uses different narrative techniques to tell the stories of Woody, Jordan, and Joanne. Each of these characters, on the surface, is vastly different, but Ware creates empathy for them by emphasizing both the ways in which their memories betray them and by showing the similarities of their traumas. At the same time, he never lets the characters off the hook for their cruelties and bad decisions, especially Woody and Jordan.

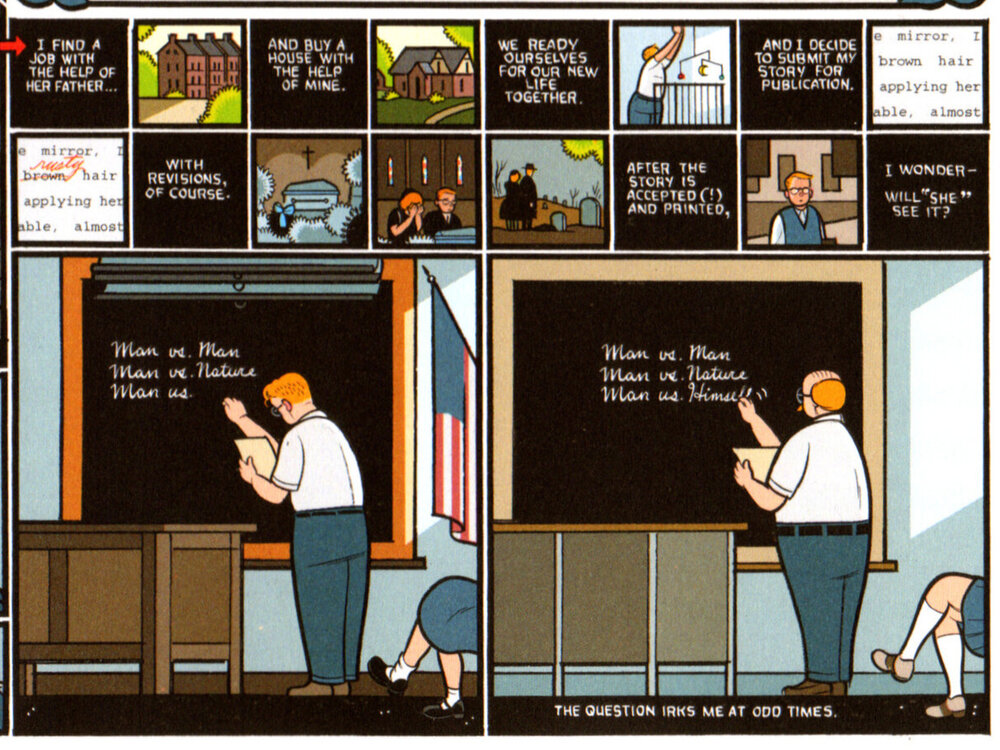

In the introduction of Rusty Brown, Woody Brown is presented as a casually cruel and befuddled man who is profoundly shocked by the passage and ravages of time. He is someone who believes that things happen to him, rather than understanding how his own sense of agency affects others. He can’t let go of the nameless woman with whom he had a toxic and intoxicating relationship, nor could he ever begin to understand her. He’s thrown for a loop when he meets Alice White, who bears a resemblance to his old lover. It’s important to understand that Woody’s chapter is mostly a reverie, as he relives and reconstructs events in a highly subjective and unreliable way.

Thus, when the reader is presented with his science-fiction story, “The Seeing-Eye Dogs Of Mars,” it’s through Woody’s mind’s eye years later. Key details on the page are slightly different. For example, the unnamed wife of Rusty the explorer has brown hair on the page, but she is described as a redhead. The dialogue she utters on the page is missing in the actual prose that’s revealed at the end. Everything is fuzzy. One of the central themes of the sci-fi story and Woody’s own reverie is the way emotional trauma muddies memories, and, by association, muddies identity. In each story in the entirety of Rusty Brown, there are key passages where the narrator tells us that their memories of a particular period are fuzzy. Art imitates Woody’s life here as he was never fully able to come to terms with his grief but was also unable to see how his own actions contributed to this trauma. As a result, his Rusty character commits monstrous acts but can never quite remember how or why things got to be so bad.

Empathy and understanding aren’t just ways to connect to others. They also promote healing and self-examination without the neurotic urge to control others. That urge is prompted by trauma, and, in the Woody Brown story, it’s clear that his ex-lover has been severely traumatized. The story suggests that she’s a kept woman for Woody’s boss, a newspaper editor. She has no control over her own life or sexuality, and the hundred dollar bill she forces on Woody in an effort to get him to leave suggests that the relationship might be purely transactional. So what does she do? She puts her trauma on Woody as a way of feeling control. She laughs at his emotional needs and uses him sexually. He’s confused and hurt but never sets up any kind of healthy boundary. He breaks his glasses, the quality of his work deteriorates, and his life spirals out of control when he’s with her. She doesn’t care, and she’s not capable of caring. All she wants is that temporary narcotic of dominance through sex.

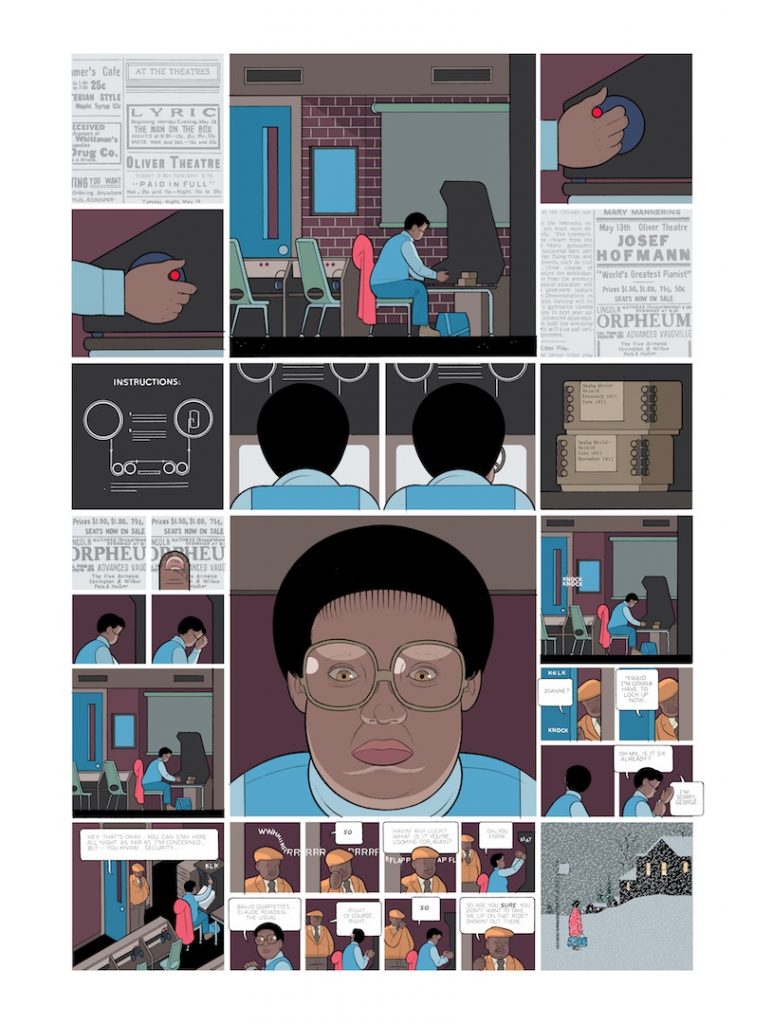

In the book, Ware compresses that spiral on a single page with nearly two hundred panels. This is partly as a way to show how off the rails Woody’s life was going, crashing through the page at breakneck speed. It’s also a way of portraying Woody’s memory of the events at that point: so painful that he can’t linger on them for more than a second. Even the most revealing parts are a blur. It’s not just pain, but a total lack of control over his own life. It’s not an accident that Woody’s character in his sci-fi story, Rusty, is always trying to assert his dominance over his environment and wife, clumsily and viciously. Emotional abuse tends to run in that sort of cycle, where the abused/dominated person seeks a victim of their own to compensate for their feelings of worthlessness.

When Sandy, a secretary who clearly pines after Woody, takes him in and cares for him, he quickly moves to dominate her (and it is no accident that when they finally have sex, he is on top) physically and emotionally. It doesn’t take long for him to resent his wife for her submission, though the empathy-challenged Woody can’t connect his new behavior to that of the woman who broke his heart. He mistakes her manipulation for love because he is so starved for affection that he can’t tell the difference. When he’s finally shown real affection by Sandy, he’s so traumatized by his experiences that he can’t reciprocate it. Indeed, he’s far more concerned with his vicious revenge fantasy in the form of his story than anything else.

Woody is a pathetic figure precisely because of his unwillingness to confront and understand his own trauma and how it has affected him throughout his life. Instead, he chooses to resent his wife and son. His interactions with Joanne Cole are interesting. A flashback where he attacks her at a meeting using racist language, accusing her of receiving special treatment to get the job, is ironic because Sandy’s dad helped him get his teaching job with no qualifications. Later, he drunkenly accuses her of having sex with the school librarian, but it’s because he wants to hit on her. As readers, we feel bad for his sad and lonely childhood and the cruelty inflicted on his dog, as well as the cold nature of Woody’s father. The bewildered Woody never knows what hit him in his relationship, and that’s also a shame. However, Ware makes it clear that Woody has plenty of opportunities to change, grow, and, most importantly, connect, but he chooses not to. Woody Brown will never know where the time went.

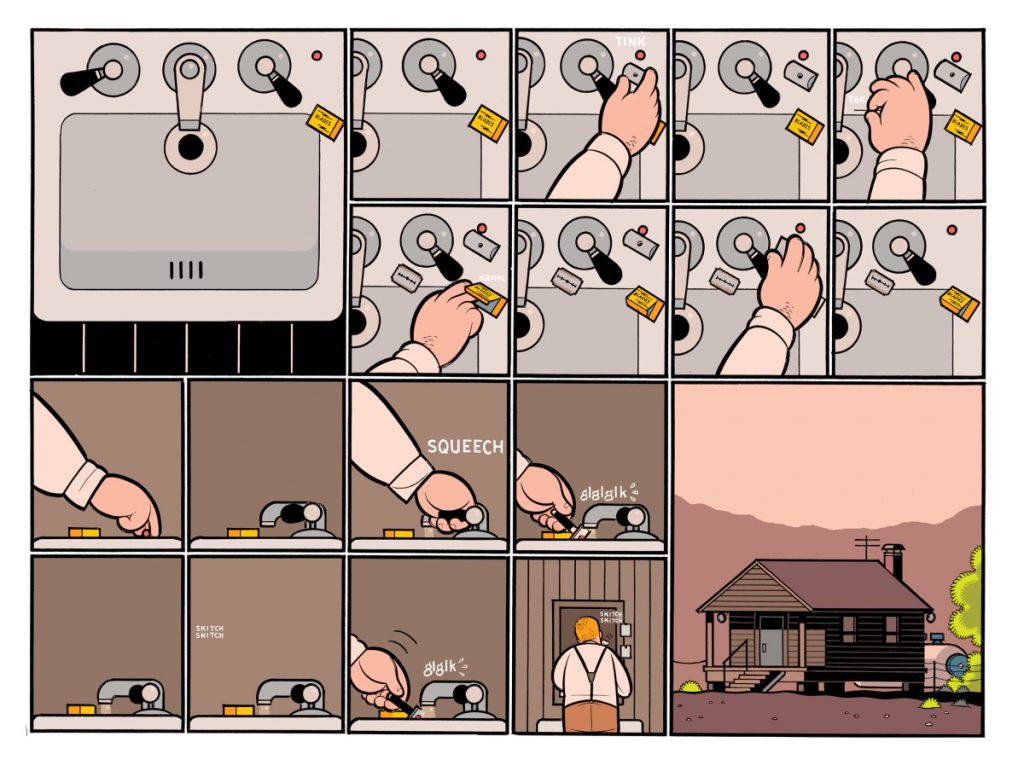

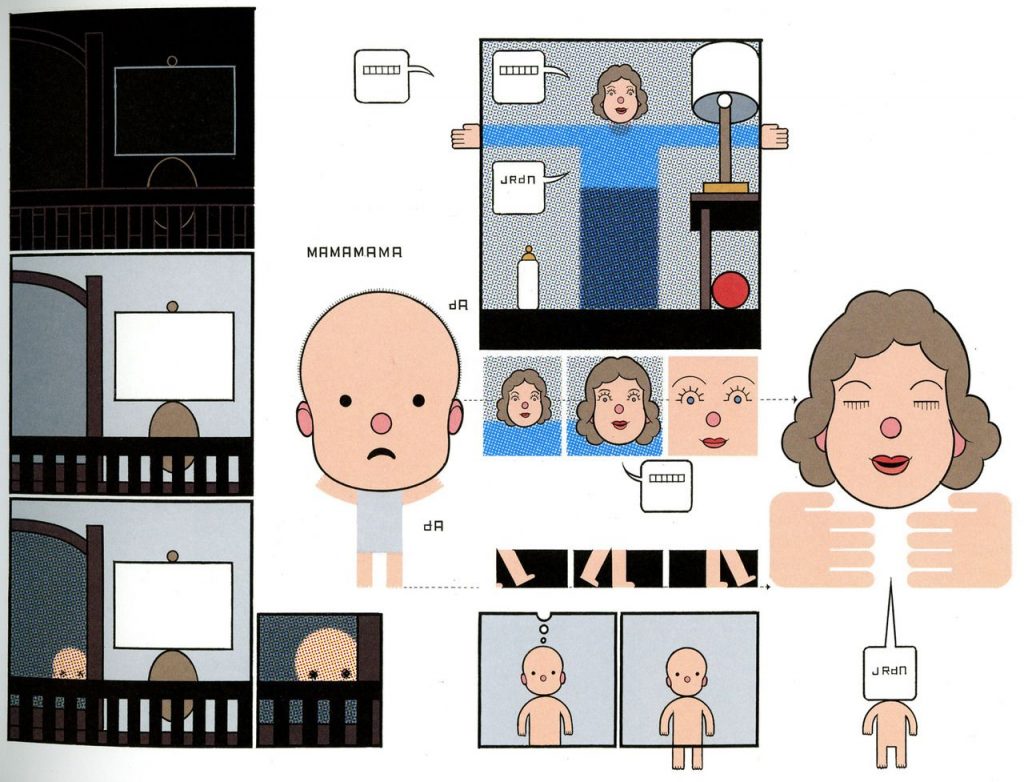

Ware takes a different approach with the character Jordan Lint: it’s a year-by-year chronology of his entire life. Each page in his story roughly represents a moment from a year in Jordan’s life, with certain pages slowing down and others speeding up the narrative at times. Writing an alpha male character like Lint is a departure for Ware in many ways, and it’s obvious that he took great care in writing as nuanced a story as was possible for him. Writing him from birth to death is Ware’s strategy in portraying those moments of humanity in a character who is otherwise a racist, a homophobe, a bully, and an abuser.

Formally, Ware really digs into how perception and memory blur. From the opening pages of Lint’s first dim memories perceiving shapes and sounds to his dying moments as his brain ceases to function, Ware emphasizes what a neurological miracle life truly is. It’s a way of noting that even Lint, odious as he is, is also a miracle. This reflects Ware’s essentially humanistic point of view, one that extends to everyone. Seeing him as a child reminds the reader that Lint was once vulnerable and experienced trauma, as his father abuses his mother. His mother later dies when he’s very young, and his father quickly remarries a very nice woman. When Lint is a teen, his best friend dies in a car crash that’s Lint’s fault.

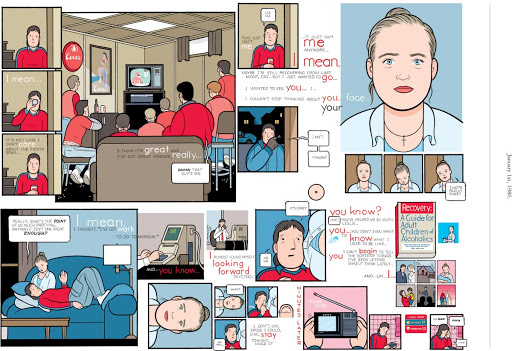

All of this information explains the roots of his behavior, but Ware doesn’t excuse any of it. Indeed, when compared to the ways in which the other characters in the book face trauma, abandonment, and rejection from parental figures, it becomes clear that Lint blames everyone but himself. He always takes the easy way out, deflecting blame. When he does try to better himself, it doesn’t take much to push him to be selfish again. Because of his wealth and connections, he has the ability to do amazing things, but, instead, he chooses lazy, venal, and narcissistic pursuits. He serially alienates partners and children but occasionally tries again, each time failing in new ways.

(Memory is the engine of our own personal narratives. It provides a steady-state of self and identity, allowing us to think of ourselves in a particular way. In Rusty Brown, Lint has a sainted memory of his mother, only the reader learns that a key memory about a ladybug actually involved his stepmother, not his mother. It’s the first instance of his memory being unreliable in creating the persona we see. The more devastating memory comes from one of his sons, who writes a memoir about Lint breaking his collarbone as a small child, screaming at him because he thought he was gay. Ware depicts this in a series of horrifying child’s drawings done in blood-red. Tellingly, this is one of his son’s vivid memories — not Lint’s. His son processed his trauma through art (a running sub-theme in the book), a difficult process that likely helps him to heal. For Lint, it is the last straw, and he dies alone, disconnected from everyone in his life.

The final chapter of the book features third grade teacher Joanne Cole, a kind and long-suffering woman. There are elements of her story that are similar to those of Woody Brown and Jordan Lint. She doesn’t actually know her father, starting her life off with abandonment right away. Her mother loves her younger sister more than her, despite Joanne sacrificing much of her life to take care of her. However, Ware starkly points out just how privileged Woody and Lint are as white men. Cole, as an African-American woman, faces microaggressions as well as blatant racism on a regular basis, especially at a mostly white Catholic school. As a woman, she experiences sexism in the form of making less money than her colleagues, catcalls, and people like Woody drunkenly leering at her.

She sublimates her rage through the sheer joy she experiences in teaching children as well as learning how to play the banjo. Even in those two joys, racism is present on a constant basis. When she makes cupcakes for her class, one of the kids says that her parents told them not to eat anything she made. When she receives some old sheet music for the banjo, the tune has the kind of racist title not uncommon in the ragtime era. Her younger sister takes advantage of her throughout her life and ultimately forces Joanne to put her mother in a nursing home. What can she do? She just swallows her rage.

There’s a greater trauma at work here, one that’s deeply sublimated and not revealed till later in the story. Joanne loves her students but never gets married. The school librarian, George, is unfailingly polite to her, but his interest in her is unmistakable. With equal politeness, she always refuses his offer of rides home. Why does this deeply loving, caring woman constantly reject the possibility of connection? It’s because she gives up a baby for adoption when she’s a teen. It’s something she deeply regrets. The schoolchildren and kids she tutors in banjo are a substitute for the child she gave up, and so she is heartbroken when she’s promoted to administration.

There’s one African-American girl in particular named Louise whom Joanne remembers eating one of her cupcakes on that horrible day when the white kid refuses to. Except that she doesn’t, because when Joanne runs into her years later and thanks her for being nice, Louise reminds her that she wasn’t there that day. Joanne conflates other good memories of Louise as a way of cushioning that single, horrifying day.

She spends most of the story going through newspaper records, ostensibly looking for banjo-related items but, in reality, looking for birth records in an effort to connect with her child. When Janice, a woman who looks like her spitting image (as displayed in a remarkable two-page spread) walks into her office and says she might be her daughter, a lifetime of pent-up emotion spills out. It’s the connection she’s always desperately wanted. Ware is a master of body language and gesture, and the way it plays out on these pages subtly amplifies Joanne’s emotions.

Throughout the book, we mostly see Joanne refusing to react to the abuse she receives from pretty much everyone. She never cries. When dealing with her mother and sister, she sometimes shakes with anger, with little wavy lines surrounding her hands. When her daughter walks in, she starts shaking again. This time, it’s from a lifetime of pent-up grief and loneliness that she finally lets herself feel. Joanne is a person who puts the needs of others ahead of herself. No one ever takes care of her or comforts her until the very last scene of the book, when Janice holds her hand.

This is a nice thing that happens to a nice person, but it ties into the wider theme of human connection. Joanne being long-suffering doesn’t make her a heroic character any more than Jimmy Corrigan being a sad sack did. The only virtuous thing she does is not inflict her trauma on others. She allows her guilt to impede her happiness, believing that she doesn’t deserve human connection if it is not mediated through a classroom. When she gets it out of the blue from her daughter, it’s too much. It’s overwhelming. Even though she had been trying to find her daughter for years, the reality of the event in a particular time and place makes her confront her own self-loathing, and she’s just not ready.

Ware seems to suggest that we can’t stop trying to connect to others, no matter how bleak things may seem. Time is every bit as tricky as memory. Ware suggests it speeds up and slows down, warping memory. Joanne has every reason to give up, but she doesn’t. Maybe she goes about it the wrong way, in denying herself other connections, but she at least tries, whereas Woody and Lint throw away chance after chance, never acknowledging their privilege in so doing. Instead, Woody traps himself in a toxic trauma loop that he is unwilling to try to resolve, and Lint simply periodically finds new people to foist his trauma on. If we don’t try to move forward on our own, time will do the job for us. Rusty Brown features more of Ware the humanist than Ware the satirist. There are moments of dark, awkward humor, but they are always in service to exploring the broader themes of connection and rejection and the choices the characters make when facing trauma.

READ MORE FROM RUSTY BROWN WEEK

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply