Since 2016, the Shanghai-based comic artist Woshibai (我是白) has been building an extensive body of work online, all ostensibly set in a unified, instantly recognizable universe.

Their concise, silent short stories feature black-and-white drawings and surreal themes. A vending machine accepts the moon as currency. Clouds throw parties. A single tear summons a rainbow. Recurring characters indulge in acts of cosmic reverie – from a round of mini-golf with planets to stacking dominoes across an entire city. Woshibai frequently plays with perspective and scale, resolving these shorts with “plot twists” — worlds within worlds, deus ex machinas, or windows that become mirrors. The moon is accepted as currency. The clouds are kidnapped and stuffed into a mattress. The rainbow creates a moment of silent beauty across a grey city. The dominoes are run over and disrupted by a passing truck. They’re not elaborate puzzle boxes like the work of, say, Jason Shiga, but a similar playfulness with the subverting of narrative expectations is at work, albeit compacted down to the scale of a single Instagram post.

Consumed online, they’re a potent brew. Woshibai’s comics scroll well, paced perfectly for an endless stream of social media posts. Silent, short, unexpected, surreal – there’s a snackable brevity to them that’s unsurprisingly amassed a huge following, with over 200,000 fans on China’s Weibo and 65,000 on Instagram.

Games (游戏, you xi), released in November 2019, is Woshibai’s first full-length work in print. It consists of 43 short stories across 556 single-panel pages, half of which regular fans would recognize from Tumblr or Instagram. Interestingly, though, the jump from online to offline both obscures and reveals aspects of Woshibai’s work. At the level of the individual story, what was a perfectly-formed nugget within an Instagram timeline becomes a slight, seemingly incomplete fragment. But putthe fragments together and something akin to a “worldview” appears between the lines. In curating, selecting, and ordering Woshibai’s work, the book encapsulates what a disaggregated stream of posts disavows: a politics.

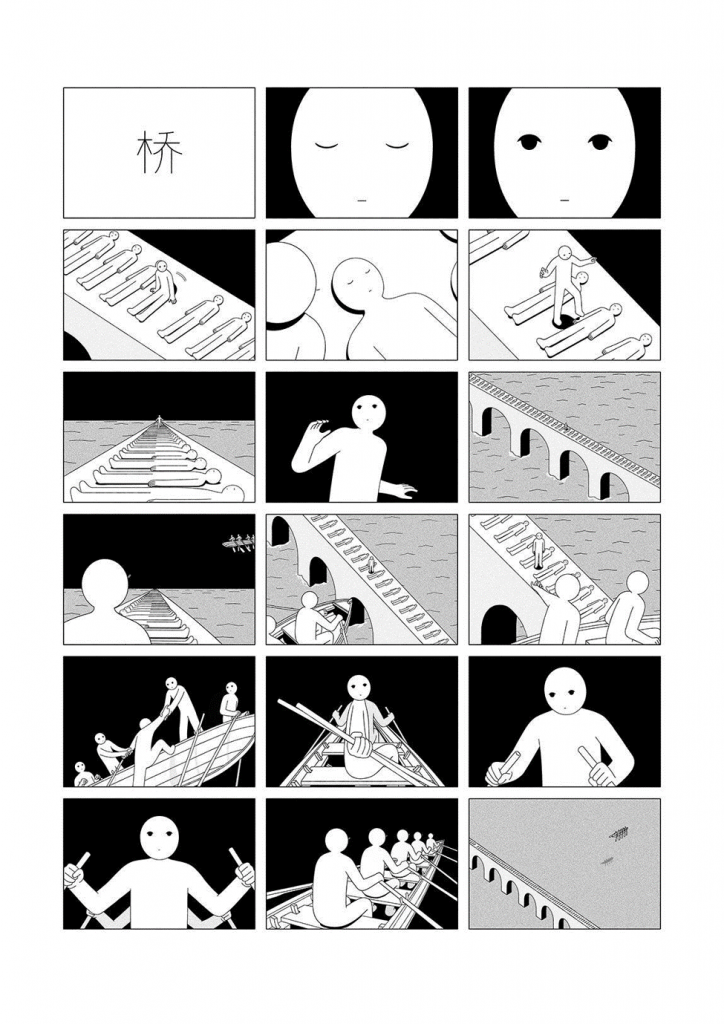

In the book’s opening short, titled ‘Bridge’ (桥, qiao), a person awakes on a bridge over an endless sea. To their left and right are a seemingly endless row of sleeping people, all lookalikes. The awakened steps over these slumbering forms gingerly, looks up into the sky, and sees a boat floating above. It’s being rowed by a few who, like them, are awake. They hail, get on, grab an oar, and row away. Slumber is traded for rote routine. But even a compromised awakening, Woshibai seems to say, is better than staying asleep.

It’s a powerful setup for the collection. What would be a short chuckle, a perfunctory “Like” and a scroll onwards online instead, here, lingers on the page. Woshibai’s shorts don’t produce viscerality but rather a non-cathartic reaction. There is a sense of suspended agency that builds across the 43 stories in this collection into one consistent revelation:

These are comics about powerlessness.

In these silences, still endings, and subversions of narrative are recurring images of loneliness, helplessness, and resignation. The stories don’t so much bend space and time as pause it, floating like motes of dust in a sunbeam. Woshibai captures a widespread, cynical view of contemporary China, but does so with a streak of nostalgia and yearning. It’s a dream-like representation of a recent subculture that trades in this sense of loss, one that’s captured the imagination of the so-called “post-1990s” generation in the country.

In memes, music, and art, it’s called ‘Sang’ or ‘funereal’ culture (丧文化, sang wenhua). It’s the feeling of being overwhelmed by rapid progress, of feeling adrift in its wake. “Sangsters” respond by rejecting ambition, leaning in to lying down, and giving in to personal reverie and indulgent flights of fancy. The cartoon Bojack Horseman is often held up as the pinnacle of “sang” thinking. At scale, across China, it’s a quiet revolution. Woshibai seems to find power in that reverie and meaning in the repetition of mundane tasks. The stories in Games read like parables: fairy tales for the “sang” generation that index political powerlessness and social disaffection.

Officially, depictions of what is deemed “sang” culture are unwelcome on state-controlled airwaves. They manifest, instead, as objects of consumer consumption — illustrations and comics key among them. Woshibai’s work, situated within this landscape, seems to serve a similar purpose as the ‘anekdot’ in Soviet Russia — snack-sized, darkly comic, deprecating, surreal anecdotes consumed as folklore. No one is reading Woshibai literally, but the repeating motifs of cosmic insignificance, thwarted plans, and vast loneliness ring true to a particular strata of urban millennial experience in China. When the media is tightly controlled, censorship pervasive, and doublespeak a daily occurence — absurdity can feel more accurate than truth. Escapism can feel more tangible than reality.

Reading Woshibai now, in February 2020, is particularly striking. Large swathes of urban China are under lockdown or quarantine, a desperate response to the COVID-19 “Coronavirus” outbreak that originated in the central Chinese city of Wuhan. With an estimated 750 million people stuck indoors — lonely, isolated, powerless — Woshibai’s work is almost prophetic in capturing the psycho-geography of this surreal, dreamlike time.

Within Games’ 43 shorts are frequent images of ‘theft’ — humans stealing from nature, haves taking from the have-nots, species cannibalizing themselves. Characters stuck in repetitive jobs — security guards, a janitor who scrubs planets clean, a woodcutter — are frequently denied something key, either meaning or compensation. Insomuch as a ‘happy ending’ can be guaranteed in a Woshibai short, it only occurs when characters act selflessly — giving rather than taking.

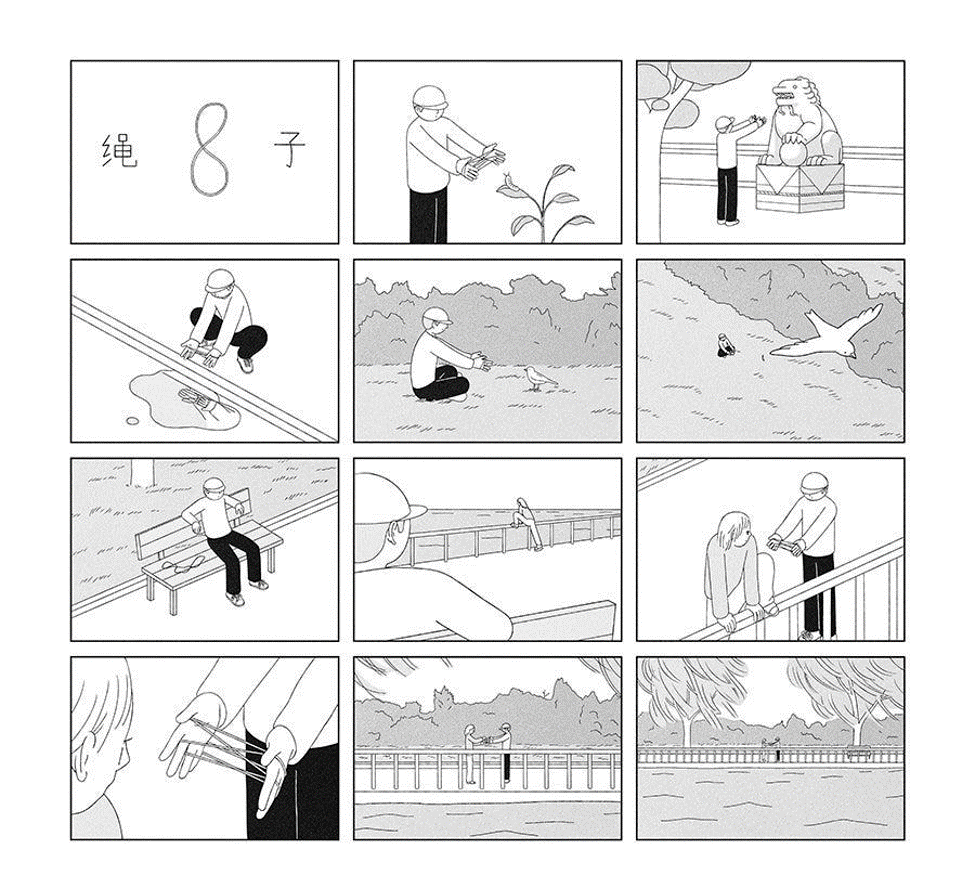

In ‘String’ (绳子, sheng zi), a capped character offers a trick with a piece of string to everyone and everything they encounter. A bird, a statue, their reflection in a puddle of water – – none of them respond. Then, they spot a person who appears to be considering throwing themselves off a bridge and offers them the same trick. It seems to work, and the short ends with the two playing together. ‘String’ is sandwiched here between two other shorts, ‘0oc’ and ‘Gather’ (收集, shouji), both of which feature lonely characters taking objects from the sky and finding that nothing changes, even with possession. Their loneliness stays in stasis.

As themes go, this is not particularly sophisticated, but as it is communicated through the slow-burn allusions of Woshibai’s worldbuilding, it takes on an air of profundity. There’s a sense of resolution here, too, as if Woshibai is tying up the strands of what you might call their “early” work together, ready to move on.

In 2018, Woshibai put out two boldly “experimental” works — Migraine and Closet –both narrative shorts drawing on autobiographical childhood memories. Another experimental short, this time playing with panel layouts, appeared in ‘GAME’, an ambitious anthology of 24 Chinese comic artists. In 2019, they participated in a collaboration with Wangxx, a Shanghai artist who’s built a cult following with her adorable comics featuring a lazy (freelance designer) seal and her sea-creature friends.

These aren’t stray instances of Woshibai breaking character, but, rather, they are portents of what’s to come from them. The shorts in Games, seen in this light, are fragments of autobiography. Its appearance in print is a full stop, a crossing over into a new phase. It’s the perfect introduction to Woshibai’s work, but it’s also the end of a chapter.

Woshibai’s rise in the Chinese comics scene has gone hand-in-hand with a nationwide flourishing of the form. Their lonely routine as an emerging indie comic artist has given way to readership, community, and collaboration. There’s a resurgent ferment in Chinese comics-making today, an energy and diversity that’s visible in the pages of anthologies like GAME, and at art festivals like ‘Singularity’ in Guangzhou. As a medium, it’s producing some of contemporary China’s most vital works of societal critique and self-diagnosis. And like the “sang” subculture that inspired many of its current leading names, it’s a quiet revolution.

The sense of melancholy and nostalgia in Games, then, isn’t for an idealized past but rather the here and now. It’s driven by a sense that the dominoes Woshibai has painstakingly stacked could be run over by a truck at any time. Success can be ominous in China today, a system that often activates heavy-handed censorship at scale rather than direct it at all content. A “scene” can be broken apart overnight. Framed within that context, Woshibai’s collection offers one additional revelation: beat loneliness, find community, and, just for a while, you might not feel that powerless anymore.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply