For cartoonists who want a way to picture loneliness, a page full of panels is a basic but effective tool. In comics like Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina and Tillie Walden’s The End of Summer, characters are literally confined in their own little boxes, seemingly unable to cross the physical — and by proxy, emotional — gutters that stand in the way of human intimacy. The comics page itself becomes an image of separation and isolation.

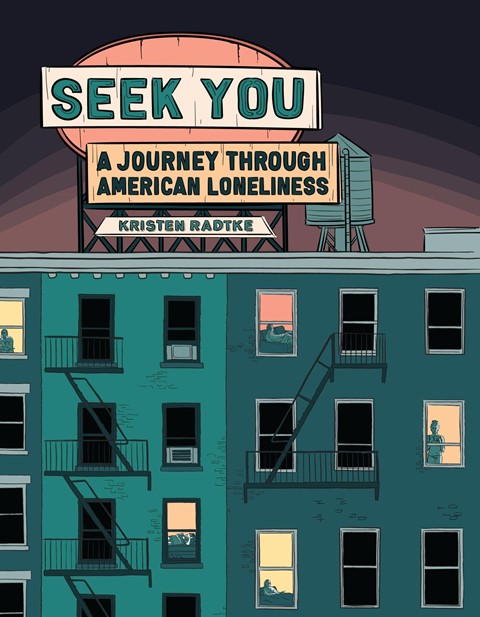

Kristen Radtke’s Seek You: A Journey Through American Loneliness (Pantheon, 2021) takes a different approach. The book uses both words and images to explore the causes and consequences of loneliness. But it does so with barely any panels. Radtke refers to the book as a “graphic essay,” and she takes the reader on a tour of many disparate subjects: pop culture, neuroscience, evolutionary biology, history, current events, and moments from her own life. While Radtke’s first book, Imagine Wanting Only This (Pantheon, 2017), relies on panels to drive a mostly chronological narrative, Seek You is her attempt to represent the experience of loneliness without the constraints of a traditional comics page. In a recent interview with Catapult, she describes her decision to work outside of panels as “super freeing.”

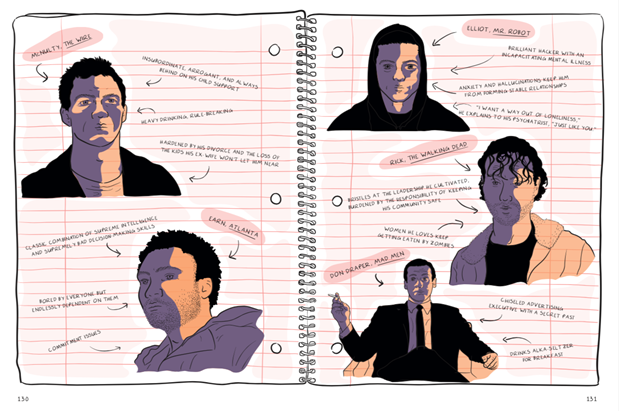

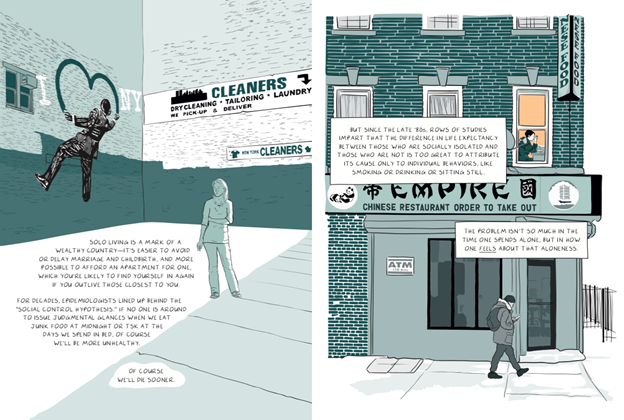

The results are uneven. Seek You is an ambitious but failed experiment that relies on a grab-bag of techniques to fill pages. Radtke picks up and discards formal strategies without ever finding a visual conceit to hold the book together. These range from wordless, full-page drawings to collage-like overlays of text and image. One chapter includes a half-dozen pages with nothing but text and drawings of Tweets — seemingly an attempt to replicate the isolated-yet-communal experience of scrolling through strangers’ internet posts. Occasionally, Radtke transforms her pages into ruled notebook paper where she presents an abbreviated history of technology since the telegraph, for example, or her analysis of lonely male characters from popular television shows. The result is a structureless, meandering book punctuated by jarring visual jumps whenever Radtke tries something new.

The book’s most compelling and fascinating moments are born from sequential storytelling. One effective anecdote focuses on The Silver Line, a British call center that offers lonely seniors a chance to talk with someone. Over the space of three pages, Radtke describes, in simple prose and fragmented images, the experiences of those callers, who often dial the hotline late at night. I remain haunted by the man who phones on Christmas Eve, ostensibly to ask for advice on cooking a chicken. Eventually the man discloses that “it’s his first Christmas since his wife died, so he thinks it’s best he learn.” The entire sequence is a powerful, concrete example of Radtke’s thesis — that humans are constantly seeking, in some way, to mitigate their own loneliness. It’s also an indictment of the way Western societies isolate and abandon their elders (though the book doesn’t pursue this line of thought).

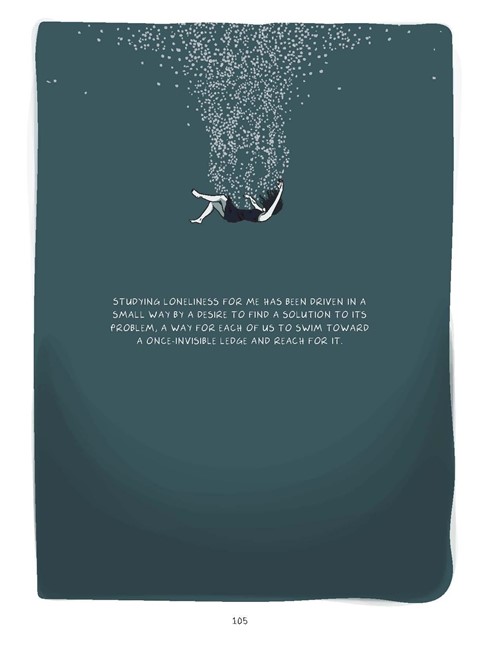

Radtke sometimes finds interesting ways to depict loneliness on the page: Seek You includes many drawings of isolated, presumably lonely people who are often framed by windows or else standing alone on the blank expanse of a page. One of the book’s most poignant scenes includes several full-page depictions of anonymous figures sinking languidly into the depths of a blue-green ocean. In words that float near the bottom of the page, Radtke writes that loneliness is like “being underwater, fumbling against a muted world in which the sound of your own body is loud against the quiet of everything else.”

But these moments of clarity are outliers. Some images are redundant, and in places the narrative text is simply a caption. On one page, a young, intense-looking Radtke fiddles with an old TV’s rabbit ears, clearly searching for a signal. The image is accompanied by the following text: “When I arranged its antennas at the carefullest angle, I could crank its knob to a single static-free channel.” In other places, potentially interesting visuals are overwhelmed by walls of prose, which made me wonder whether Seek You should’ve been a longform essay instead. Tellingly, Radtke recorded an audiobook version, which only confirmed this impression.

Even when there are possible interplays between word and image, though, the results can be strained. What should we make, for instance, of a page depicting loose groups of people, most (but not all) drawn as though their skulls are transparent, allowing us to see their brains? It’s not a literal translation of Radtke’s voice, which intones: “The brain’s reaction to social rejection is almost identical to how it experiences physical pain.” And yet, the image generates no coherent sense of meaning. The visual is discomforting, but not in a way that reflects or emphasizes the ostensible subject. It simply feels bizarre.

More often, Radtke’s page designs are just difficult to decipher. Her extensive use of a collage-like technique means different images are sometimes stacked in a discordant jumble. Perhaps such juxtapositions could, if handled well, generate unexpected insights. But here the result is more often uncertain clutter. The problem is not collage itself. Other cartoonists have used the technique with impressive results. Lynda Barry’s books on writing and drawing often include densely packed pages crammed with doodles, text, comic panels, scans of her students’ artwork and much more. What It Is and Syllabus are non-linear and non-narrative texts. Like Seek You, they could plausibly be described as “graphic essays.” Yet Barry’s books exude life, energy, and joyful motion, while Seek You feels static and listless.

Radtke’s approach to figure drawing is partly to blame. Seek You includes countless representations of people in sedentary poses: standing, sitting, lying down, looking at their phones, taking the subway. Occasionally characters can be found walking aimlessly, but even then they rarely feel alive. To her credit, Radtke’s drawings are more refined than in her first book. The characters in Imagine Wanting Only This felt uniformly stilted and robotic, as if drawn by a computer. Yet, while more technically accomplished, the people she renders in Seek You are somehow just as lifeless. Their faces are usually affectless or else filled with a dull malaise.

Perhaps the alienating experience of Seek You is meant to replicate the sickening unease of chronic lonesomeness. But I don’t think so. Radtke announced the publication of her book by expressing her hope that “it makes you a little less lonely.” To say that the book has the opposite effect is too harsh — but also inaccurate. Radtke’s book just left me feeling disappointed. It certainly didn’t live up to the overwhelming critical hype: Most reviewers have been lavish in their praise, and Seek You was even picked as a finalist for the prestigious Kirkus Prize in nonfiction.

I’m usually excited by unorthodox works, and I hope other artists continue to experiment with non-traditional graphic nonfiction. I also have no desire to police the borders of any artform, comics or otherwise. But Radtke was too quick to leave behind the well-trodden territory of panels and narrative. Seek You got lost on its way to somewhere else.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply