“Who could have seen this coming? Everyone.” Stephen Colbert gets at the problem: prescience has been democratized, spread too thin.

After the capitol riot on January 6, 2021, liberal Twitter was feverishly sharing old thinkpieces and media, from 2015 to two days ago, each proving that the possibility of a coup attempt was laid out in obvious signs for many, many months. Which, yes, all to the good, much smart writing and thoughtful art. It was pleasant to see films like The Death of Stalin and Feels Good Man still circulating, until 1984 entered the mix, and the bad readers took up too much room.

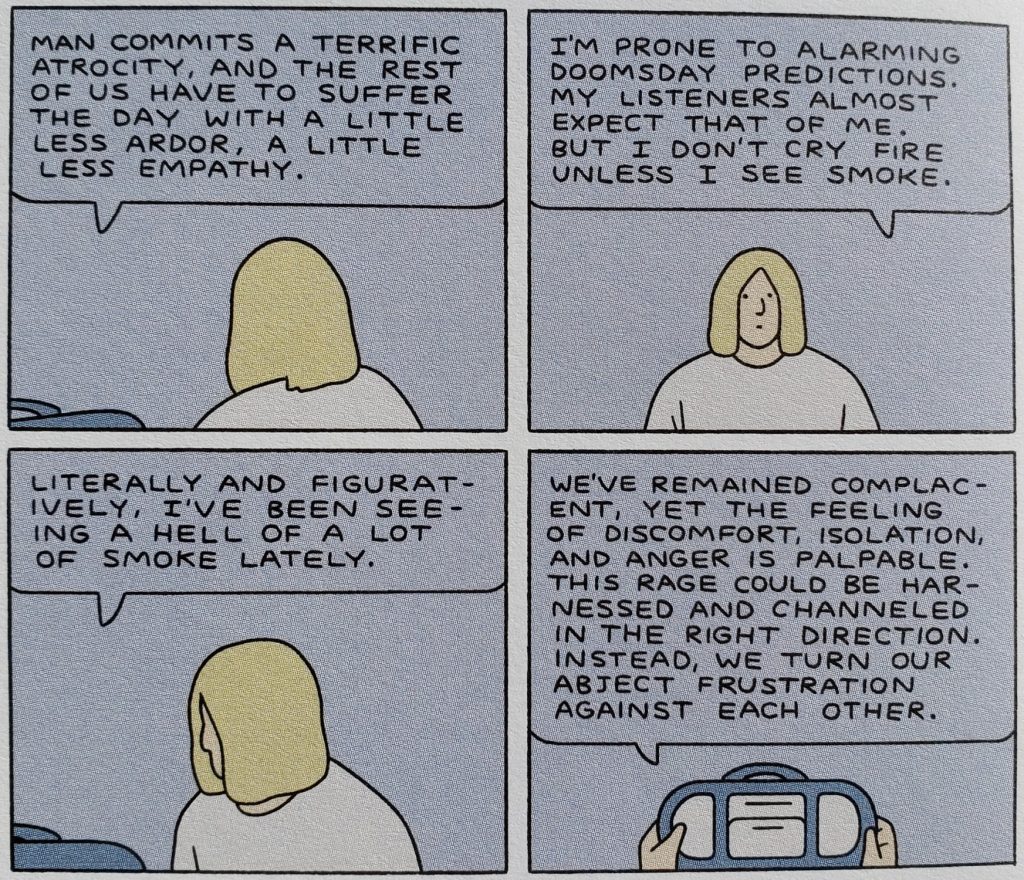

As a comics reader, though, I would have liked to have heard about Sabrina, the literary graphic novel by Nick Drnaso (Drawn & Quarterly, 2018). It fits the bill: after Teddy’s girlfriend Sabrina is murdered, she remains speculatively alive as right-wing radio host Albert Douglas raves about crisis actors, false flags, martial law, mind control, and utopic insurrection, and the internet helps reiterate these paranoid fantasies. Sabrina explores the ecosystem of disinformation and fake news, and the cloud of misery it produces: Teddy’s friend Calvin is caught up in the morass, his mental health and good humor strained. Formally, panels of minimally expressive faces get taken over and held hostage by panels of only text—emails and news stories and blog posts and rants. This all-consuming world of alternate facts sometimes renders the human element disposable.

Given its initial reception, it is even more surprising that the graphic novel has not been discussed much in the past week. In 2018, Sabrina was hailed as “a grand take on our country’s current civil and emotional climate” (R.J. Casey), “[a] dead-on snapshot of the present day” (Tal Rosenberg), and “a perspicacious and chilling analysis of the nature of trust and truth and the erosion of both in the age of the internet – and especially, in the age of Trump” (Chris Ware); it “could not be more prescient if it tried” (Rachel Cooke). For its scope, ambition, and timeliness, Sabrina brought in accolades with breadth, too, resulting in a Man Booker nomination.

Prize culture, as Sarah Brouillette argues in an essay about the Nobel Prize, is often about consecrating “literature [as] an expression of humanistic liberalism, in which the genius writer, possessed of unique visionary abilities, examines the world from the outside, determines its realities, and presents them for our contemplation as art.” Sabrina surely falls into this tradition, with its capture of the zeitgeist, and also its choice blurbs and sweep of best-of lists. Incidentally, it lines up with how comics scholar Hillary L. Chute defines literary comics in Outside the Box: “the single vision of the auteur of fiction or nonfiction comics.” Proclamations of timeliness, for Brouillette, are usually a cover for liberal commitments to these supposedly more timeless qualities of personal vision and contemplation. Perhaps one reason why we have not heard much about Sabrina, then, in the first month of 2021 is because the grounds of its critical acclaim ultimately depended more on claiming Drnaso-as-genius than on reckoning with the world Sabrina depicts.

After the riot, Drawn & Quarterly tweeted about some of its recent books by Michel Rabagliati and Walter Scott, and did not insist on the timeliness of Sabrina. Of course, it is crass to expect a publisher to piggyback on a disaster by promoting its own book, despite the many “I am Spartacus” statements of condemnation from corporate brands. And it is not like Drnaso is wanting for visibility. Just less than a month ago, Drnaso contributed a new comic to The New Yorker’s December 28th cartoon issue, an excerpt from his next graphic novel (to be published by D&Q). It would be fair to say that some readers had his images in their faces over the holidays. There were a few peeps.

Drnaso also appeared in the January 21, 2019 issue of The New Yorker, profiled by D.T. Max. In the piece, Drnaso discusses childhood abuse and consuming right-wing media, while Max focuses on the cartoonist’s artistic evolution and winning humility. Max’s profile is anchored by a bubbly portrait of Drnaso by Chris Ware, drawn from a lightbox’s point of view and making Drnaso seem focused and meticulous. When it comes to Sabrina, Max praises the graphic novel’s “chilly veneer” and its “ethic of subtraction”: simple dot-eyed faces, muted color palette, human-free environments. Reading Sabrina, he then writes, “feels almost like an antidote to the hectic Web sites its characters are so immersed in,” which suggests that the form (the grid, the pacing, the whole affectless style) works to counter the content, that the book itself is an oasis away from fringe media. Drnaso’s vision—how he sees—transcends the grossness of his subject matter. This idea of the antidote is interesting because it puts pressure on what some have considered a weakness of Sabrina: the monotony of its images, too many opaque masks.

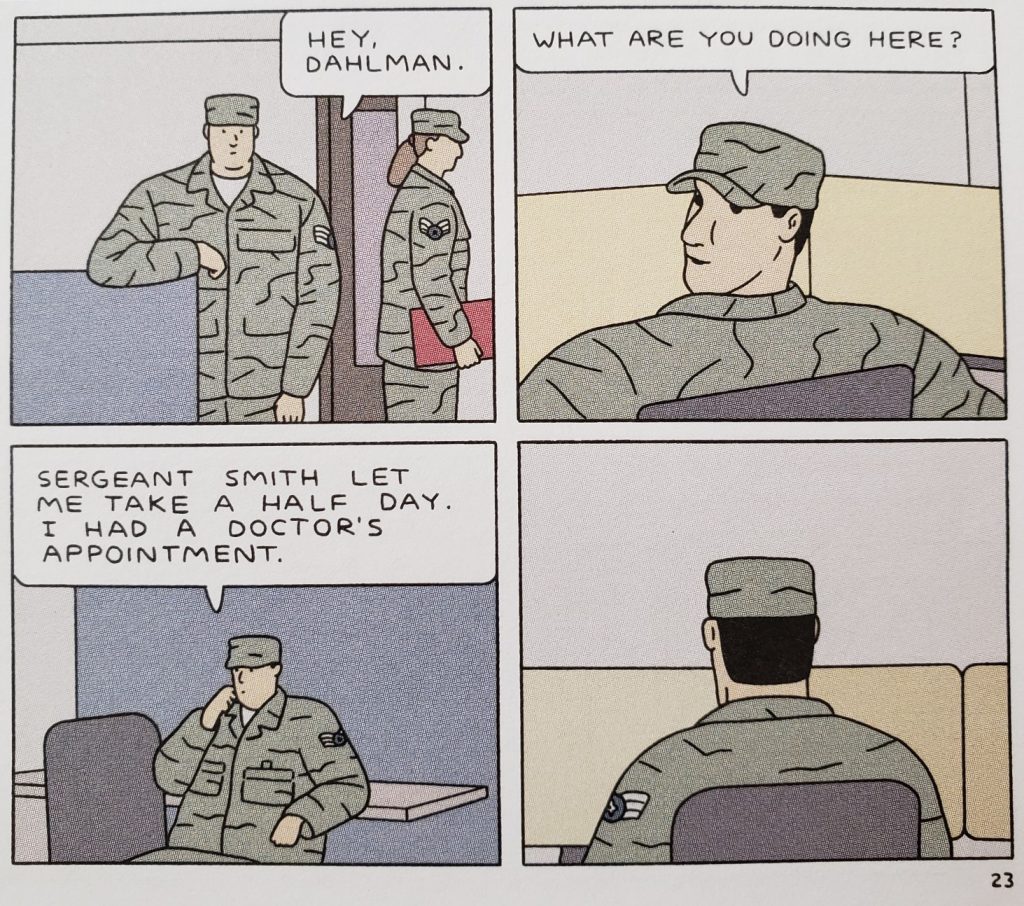

I want to consider a moment from Sabrina that I really like, one that illustrates the comic’s own search for ways outside of monotony. On pages 22-23, Calvin arrives at work, an office in an Air Force base. Calvin had taken the day off to pick up Teddy and get him settled, but he makes up an excuse a few times as he talks to people (“I had a doctor’s appointment that she had to push back to the afternoon.” Next panel: “Nothing serious. Just a check up.”). He tries the excuse again, but no one cares. Drnaso ends both pages of the double-page spread with the back of a head, but the panel on 23 is silent, its most notable feature is the square of black hair in the dead center. In the scheme of the book, it is refreshing to see the back of a head. It withholds emotion even more than a blank face does, replacing it with a sort of mysterious provocation: the black box of a brain, forever unreachable. The postures and dialogue work well together, while the samey faces in the book often fail to register any mystery.

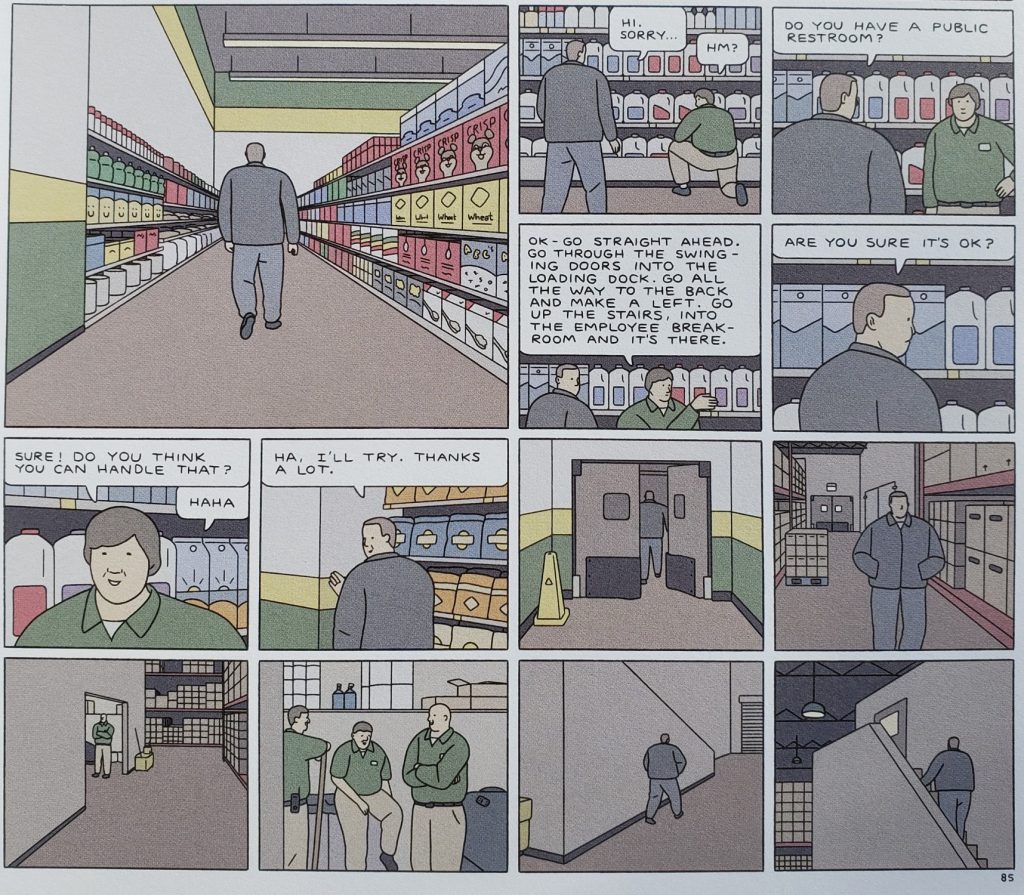

At its best, Sabrina links the black box of the human brain to the eerie facades and recessed structures of a capitalist, militarized America: there are “black sites,” abandoned guest rooms, inner sanctums, endless corridors, even hidden grocery story public bathrooms. Paranoia is baked into the environment, which suffuses into a low-level anxious mood.

The cliché about prescience is “eerily”: when intuition turns out to be accurate, it produces unsteadiness, queasiness. How could the now be contained in the past? But the present changes, which results in a mismatch between then and now. Perhaps it is the case that the pervasive mood of Sabrina is spot-on and clear-eyed about the present and that Drnaso has summed up the Trump era with troubling immersion and insight, but what if, in the light of 1/6, the flat images of the comic necessarily miss out on the chaotic, dynamic, and difficult images from footage of the riot, with more screenshots emitting new power every day since? The faces and gestures caught at the event are resolutely not blank or empty: there are howls and grins, fraught and wild faces, dramatic poses; there is rage, delight, and fear. The right has refused all masks and embraced the costume.

This is far from the quiet tease of introspection and subtlety across Drnaso’s minimal faces. The theatrical nature of 1/6 demands a different kind of reading for such a wide array of actors, as in the image-analysis of Tom Birkett and Clint Smith. Even this cartoon from Niccolo Pizzaro gets at the stage-managed hyperbole of faces. If the political cartoon is an appropriate venue to depict this exhibitionism (i.e. with the malicious cuteness of Matt Bors cartoons or the dripping grotesqueries of Warren Craghead), then, in contrast, Sabrina’s placid exterior and repressed surfaces cannot offer the opportunity to face the faces. Perhaps it cannot meet this new present.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply