Part biography, part autobiography, part political treatise, part comics journalism, Ali Fizgerald’s debut graphic novel, Drawn to Berlin (Fantagraphics, 2018), wears a good many metaphorical “hats,” but I’ll be the first to admit — “Eurocomics,” it could be fairly argued, may not be one of them, given that its author is an American living abroad. That being said, it’s set in Europe (obviously), centers on the lives of people emigrating to Europe, and also fits well within several narrative and artistic traditions associated with European comics (long-form storytelling, advocacy for a clearly-articulated point of view, decidedly fluid art that emphasizes physical bodies and body language, large and inter-generational character ensembles, etc.), so it’s my considered opinion that Fitzgerald’s place of birth doesn’t preclude her from being a “Eurocomics” cartoonist.

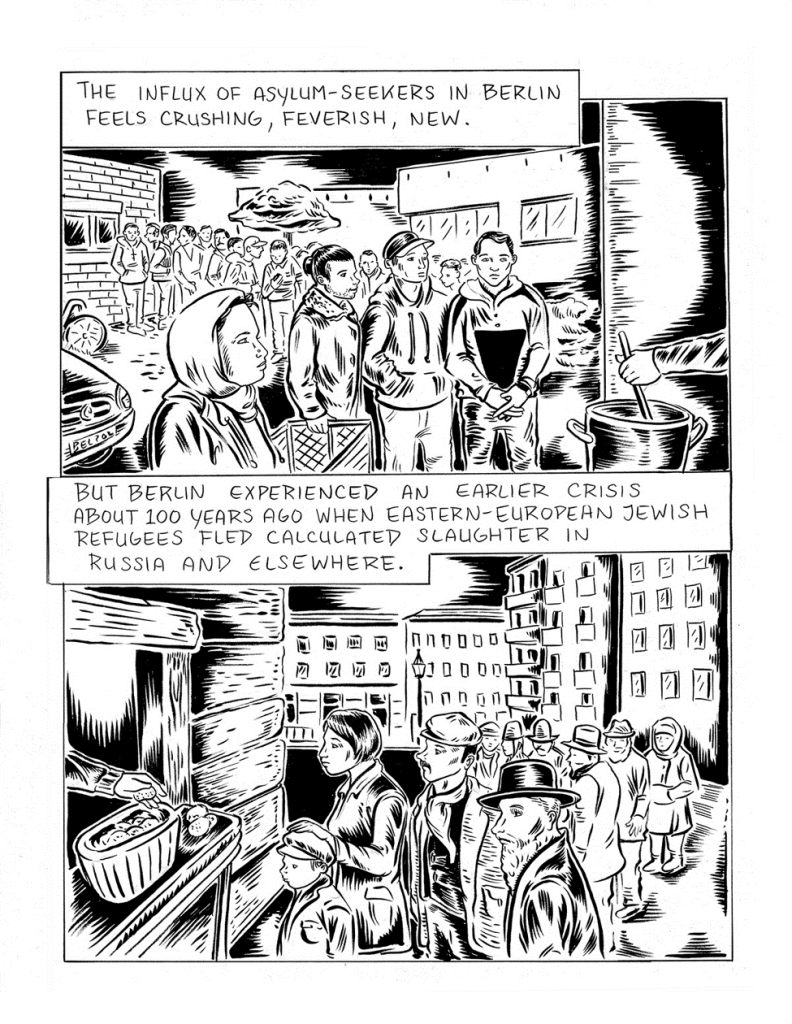

Drawn to Berlin is a robust and invariably engrossing first-hand account of immigrant resettlement in Berlin at the height of Germany’s so-called 2015 refugee “crisis.” This, however, is no garden-variety piece of visual reportage in that it takes a very unique point of view which states that art is the one true “universal language” that can bridge all cultural, racial, and religious divides — at least for brief instances, which tend to be both quite and quietly profound. And it’s Fitzgerald’s contention that those occasions of commonality, like when everybody in a room is able to recognize Spongebob Squarepants regardless of where they’re from, form a baseline from which something akin to actual understanding can develop and grow.

For my part, I hope she’s right, but this book is by no means a 200-page “Kumbaya moment.” Fitzgerald strikes me as at least a guarded optimist, but as an art instructor at one of the so-called “bubble shelters” that served as “ground zero” for all things resettlement-related, the simple fact is that she’s been too close to the situation to look at things through rose-tinted lenses. And as readers, we’re the beneficiaries of this, to use a painful cliche, “no-holds-barred accounting.”

Bobbing and weaving between relating the truths of her students’ lives and her own struggles to document them — individually and collectively — with authenticity and accuracy both, the central conflicts that emerge are both external and internal: what hope can be offered to the dispossessed in a country where so many are resistant to their presence? And how can Fitzgerald herself give voice to their backgrounds, their aspirations, their struggles, and their needs without, as she so eloquently puts it, “colonizing their stories”? A thoughtful approach to such delicate subject matter is absolutely essential, without question, and, in Drawn to Berlin, Fitzerald ingeniously weaves this into the narrative both explicitly, in its tone and candor, and structurally, as a good chunk of the book is spent on the author’s questioning of both herself and her motives in regards to its creation.

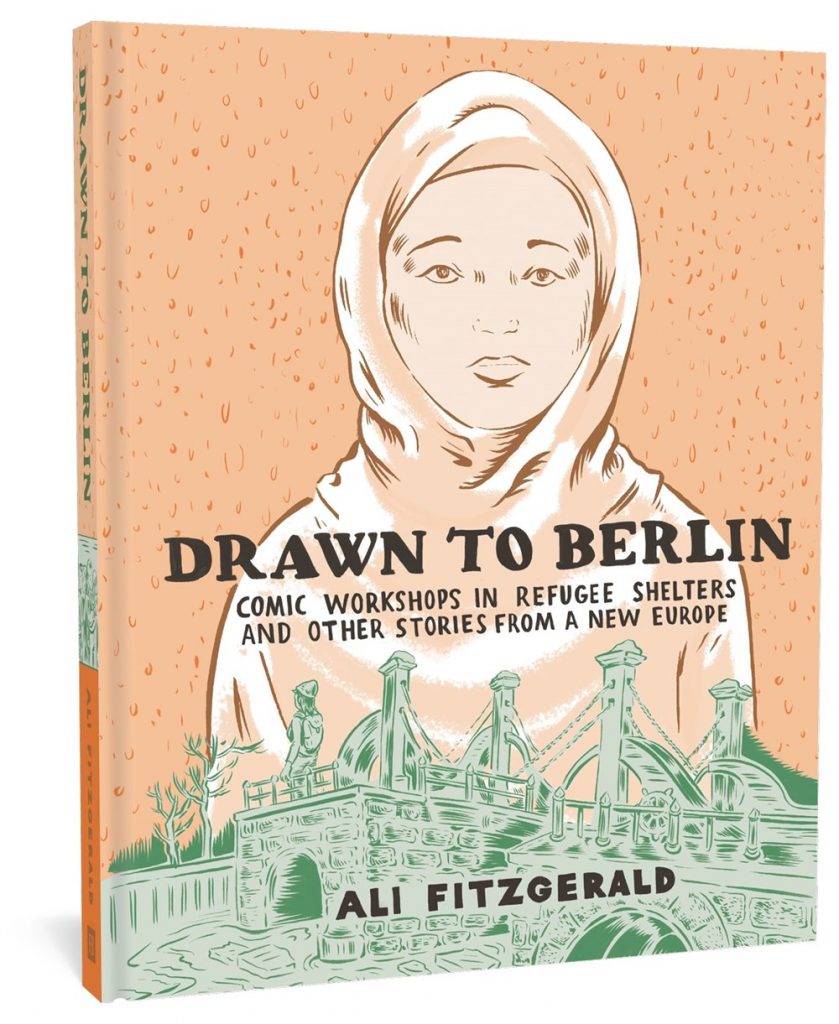

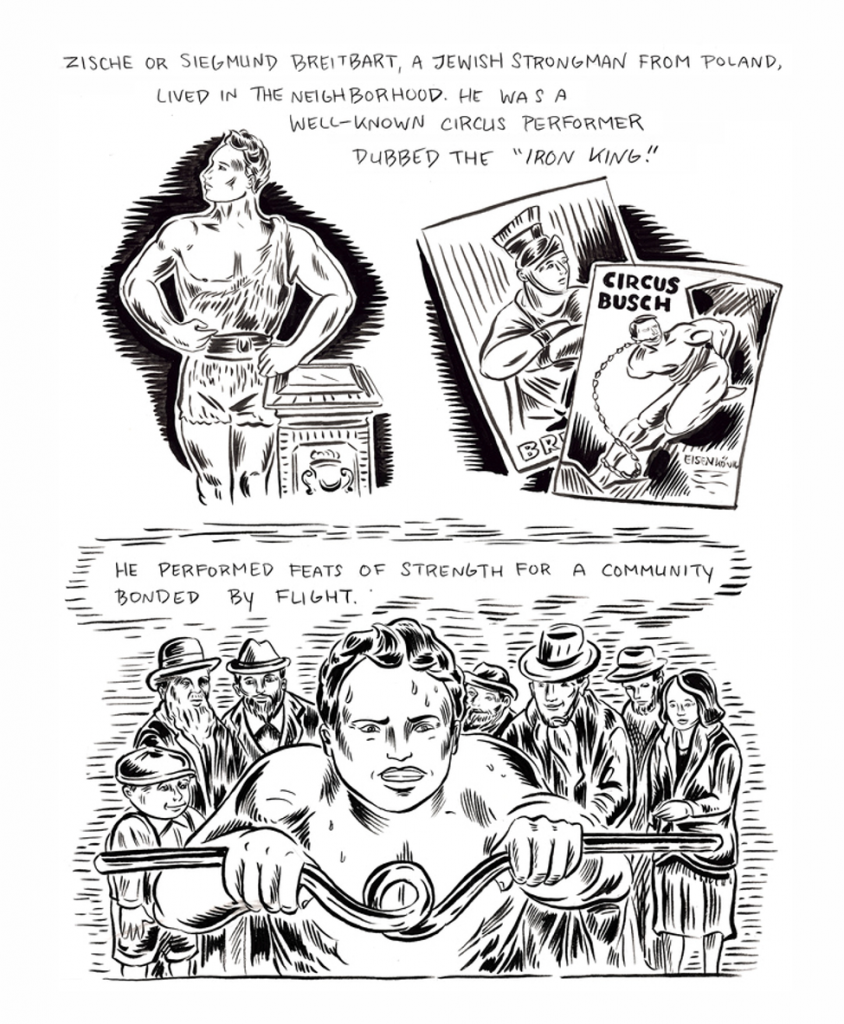

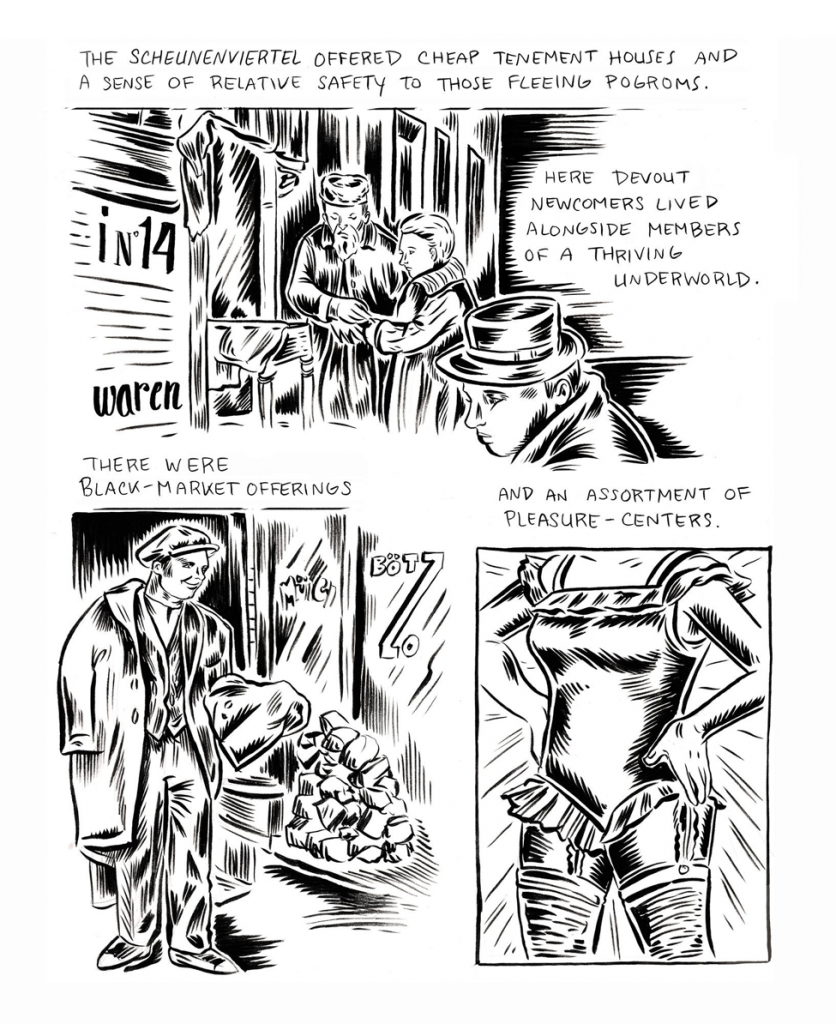

This kind of introspection can often lead to a slower-paced story, but balanced as it is with several short-form biographies of newcomers, a historical recounting of immigration in Germany, and a comprehensive view of the then-contemporary refugee influx as viewed from the inside, this graphic novel actually moves at something very much akin to breakneck speed. This is aided in no small part by Fitzgerald’s dynamic illustration, a blend of richly-detailed linework with woodcut undertones, incredibly lifelike portraiture, meticulously-rendered backgrounds, numerous borderless panels, and even pages, that see one story flow into another with grace, and that subconsciously emphasize the interconnectedness of all of us.

In fairness, Fitzgerald’s art style isn’t entirely original (whose is?), but even when her influences are obvious, she undercuts any arguments that can be lodged against her by, say, inserting a Charles Burns book into a panel that owes more than a little to his use of rich, inky blacks. This is no mere exercise in navel-gazing for its own sake by any stretch — Fitzgerald has a sense of humor about herself that is both pleasantly surprising and uniformly well-timed. Don’t expect a million laughs — this isn’t really subject matter that lends itself to them — but do expect her to use humor in an insightful, humane manner at just the times when it’s needed most.

Which isn’t to say that pathos and even heartbreak don’t abound herein. Some of this is to be expected, unfortunately, given the tragic backstories of so many refugees, but some of it is surely unexpected, as well: the transitory nature of shelters such as the one in which Fitzgerald was employed saw a lot of people coming and going without explanation or incident, and getting to know someone vicariously and then having them suddenly gone, to who knows where and for who knows what reason, leaves a pang of regret in readers along with, of course, a hope that they’re doing okay — wherever they are. Still, their absence can and does sting — and one can only imagine how much more profound that sting was, and no doubt remains, for Fitzgerald herself.

Trust me when I say that I’m hesitant to label any book as a “flawless” one, and, in all candor, there are a few instances where Fitzgerald doesn’t get the narrative balance she’s clearly striving to achieve exactly right, but even those small “failures” are noble ones. With Drawn To Berlin, Ali Fitzgerald has crafted an all-encompassing work that matches technical skill with heart, storytelling smarts with journalistic integrity, and bio and autobio authenticity with moral idealism. It’s extraordinary, unforgettable, and an absolutely essential reading experience.

Read More From Ryan Carey @ SOLRAD

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply