In September I started teaching college and pre-college, just a couple classes two days a week. It’s the best job I’ve ever had, and I’ve had many. I get paid decently well to sit in a room filled with a diverse group of bright and phenomenally talented young people. We discuss their ideas and goals and plans for the future. I do my best to teach them everything I know of the craft of cartooning (not nearly enough) and they astonish me, and delight me, and make me laugh.

The classroom is brand new and up-to-date, with ergonomic chairs and sturdy drafting tables. Skylights overhead let in the light on dreary winter days. The outside world rarely encroaches, except when there’s a “shelter in place” drill.

Nevertheless, it’s often painful for me to discuss a future I can hardly fathom. “Who cares about pitching to an editor,” I want to scream, “when koalas are going extinct?” When my students leave my room, they go back to jobs and care-taking responsibilities and the crushing burden of student debt. Many of them are particularly vulnerable to hate crimes and police harassment, being queer, being black and brown, being here on student visas.

Recently in a critique, a student who made a comic critical of the meat industry expressed a fear of being “too didactic” in her work. I could empathize, although frankly, I think we have a great deal more to fear from avoiding difficult topics than from hitting people over the head with them. That said, we’re in the midst of a fertile moment for political art. Directors like Paul Schrader, Jordan Peele, and Bong Joon Ho have demonstrated over and over again that movies can send a powerful political message without sacrificing humor, suspense, character development, or aesthetics. Likewise, in comics, Ezra Claytan-Daniels and Ben Passmore successfully satirize the very activist communities to which they belong without diminishing their importance in combating the military-industrial complex that is holding Americans hostage in their own country.

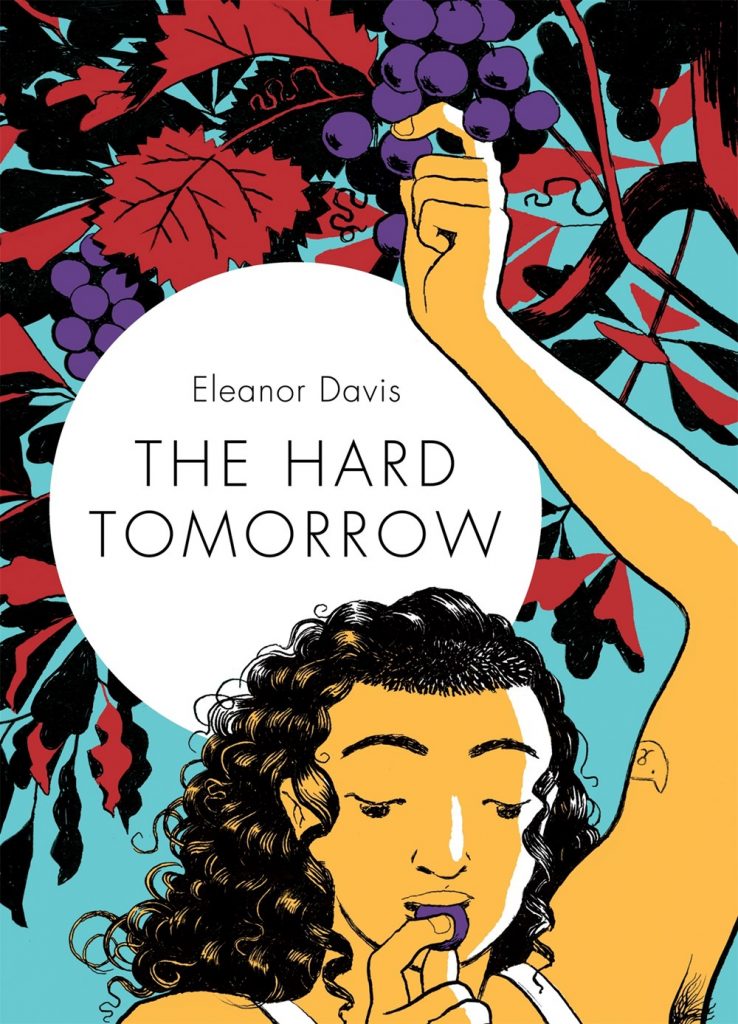

What is the point of making art in this climate? How do we get out of bed and carry on? How do we express our love for one another when a sense of crisis pervades? Are the fascists lashing out in their death throes or are they just beginning to gain momentum? How do we fight back without sacrificing our bodies? What is a good life? What is a good death? These are the only important questions, and they are the questions that Eleanor Davis has been asking, with no easy answers, in staggering works of fiction and non-fiction, for years, and which she continues to investigate in her most recent work, The Hard Tomorrow.

Set in an unnamed Kentucky town in either the very-near future or a very slightly re-imagined present, The Hard Tomorow follows Hannah Plotnik, a young woman hoping to conceive a child with her husband John, a kind but unmotivated weed dealer who has promised to build them a house. In the meantime, Hannah and John are living in their truck and surviving on Hannah’s income as a caregiver to an elderly woman. Conflict arises when Hannah becomes torn between her personal life and her work as an activist with the organization H.A.A.V, Humans Against All Violence. Much of this subject matter seems deeply personal to Davis, herself an activist and a new mother. It’s personal to me as well, and it will resonate with anyone who has been involved in activist organizations, punk communities, or artist or farming collectives. I know iterations of these characters. They are familiar to me, from their speech to their clothing to the interiors of their homes.

Davis has an eye for detail, but she’s also a stunning draftsman, and The Hard Tomorrow sees her at the absolute apex of her skill as a visual storyteller. A great cartoonist is a smart cartoonist, and Davis knows exactly when to economize and when to pull out all the stops. Letting go and working faster than you think possible can be terrifying. Cartoonists tend to be control freaks, and it’s hard to overcome the fear of making a “bad” drawing. It’s also the only way to get good. I’ve assigned Davis’s book You & a Bike & a Road to my students for the Spring semester because of its moving content but also because it’s an object lesson in economy. All the information that needs to be on the page is there — nothing more and nothing less.

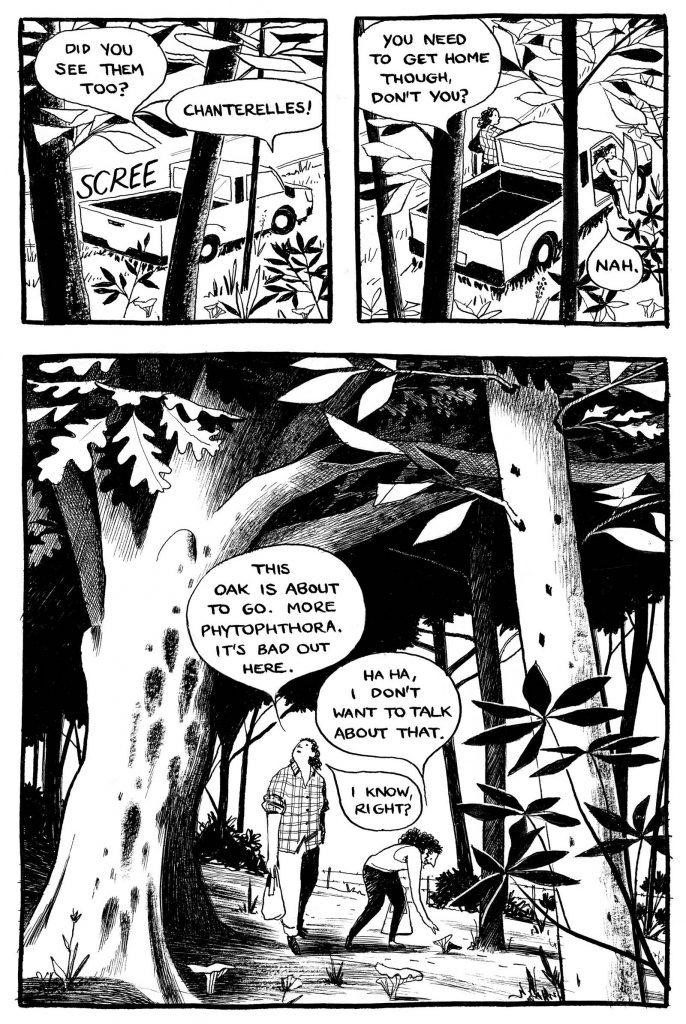

By contrast, The Hard Tomorrow is, frankly, luscious. A sequence in which John becomes stranded in a summer storm made my pulse quicken. As he runs for cover, rain slices the blackened sky in visceral white slashes and water roils on the hood of the smoking car like electricity from a Tesla coil. Not all cartoonists have a great design sense. Eleanor Davis is a master designer with the compositional instincts of a storyboard artist or animator. She produces full-page illustrations and lavish two-page spreads that drop the reader head-first into forest clearings, roiling crowds, and thoroughly imagined domestic environments.

I often have to remind my students to draw background details. Young artists starting out are often so focused on figure-drawing that they forget the importance of place. Davis’s attention to detail is startling but the drawing is never fussy or over-wrought. There is a bit of a manga influence in the character design and some of the black-spotting choices. Like Osamu Tezuka, and contemporary masters Sammy Harkham and Tommi Parrish, she juxtaposes the soft, organic shapes of the human body with carefully composed, harder-edged backgrounds to create panels that thrum with the best kind of tension but look natural and entirely effortless. I follow Davis on Instagram, so I get peeks at her process, which is not effortless (no cartoonist’s is). Sometimes, when I’m having a rough day at the drawing table, I remind myself “sometimes Eleanor Davis has to paste in corrections too.” I’ve become aware of her approach to writing, which involves editing numerous drafts of both scripts and thumbnails before moving on to the finished artwork.

With each subsequent book, Davis has been steadily pushing her own boundaries, and as a result, The Hard Tomorrow is even richer and more fully realized than her previous efforts. Many of the short stories in Davis’s 2014 collection How To Be Happy feel somewhat fragmentary, like ideas wrestled from the ether and put to pen before they could escape. The Hard Tomorrow, on the other hand, has a conventional story arc, but it ends with a kind of visual ellipsis. At first I was frustrated. I wanted some kind of resolution. The longer I sat with it, though, the more I came to feel it was the only possible conclusion, a beginning where an ending should be.

READ MORE

Leave a Reply