For the third issue of NOW, editor Eric Reynolds dipped deep into the international pool of cartoonists, including many first-timers for the anthology and English-language comics in general. In addition to Israeli regular Keren Katz and familiar German cartoonist Anna Haifisch, there was also Anne Simon from France, Roberta Scomparsa from Italy, Marcello Quintanilha from Brazil, Jose’ Ja Ja Ja from the Netherlands (by way of Spain), and Nathan Cowdry from the UK. Aside from not having a theme, this issue of NOW resembles an issue of the S! anthology from kus more than anything else.

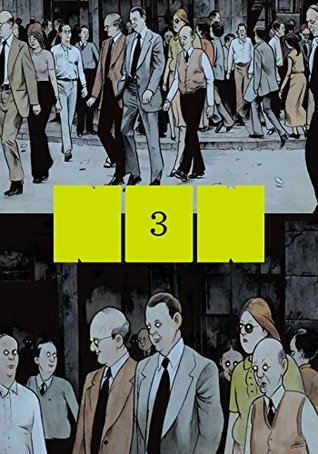

The cover, featuring a street scene, is split in two. The bottom half is a close-up of several individuals from the top half, and it serves to emphasize their eyes are literally blank. This is the work of horror artist Al Columbia, and it’s subtly unsettling in the same way that much of his work is. The horror of the cover continues with the one-pager by Jason T. Miles on the first page turn, whose grotesque and distorted figures are in service to an anecdote about a “Strangers On A Train”-style deal where two people agreed to rid the world of each others’ problems, only to eventually come into conflict. The storytelling is oblique but evocative.

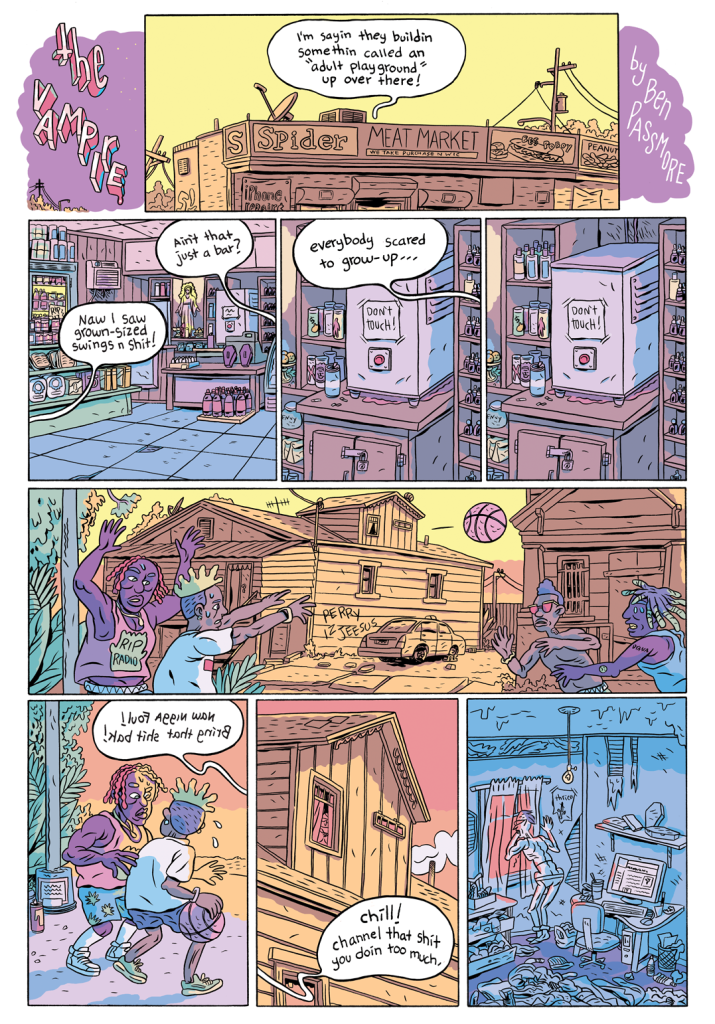

These opening images lead into the opening story, Ben Passmore’s “The Vampire.” It’s a hilarious take on aspects of the monstrous legend, like being invisible to mirrors and having to stay out of sunlight, in the context of a black vampire who lives next to a convenience store and hits on women, calling them “Andromeda.” It all seems ridiculous until something horrible happens, which the vampire simply shrugs off. Passmore specializes in day-glo colors, which is fitting given the twilight setting of this story. It’s a story about how even the biggest idiot who possesses enormous power is a threat to the marginalized, simply by virtue of exercising that power without considering its consequences.

On the subject of monsters and myths, Anne Simon’s suite of stories are about the horse goddess Aquina, Pan, and a star-crossed couple, Armida & Rinaldo. Using a blend of pastel colors and a cartoony style (that French cross between clear-line naturalism and exaggerated facial features to depict emotion), Simon’s stories are a mix of mythological conflict and romance, with a kid named Pino thrown in as an observer. The way Simon veers from ancient to modern over the course of these three stories, and the way Simon changes the size of her characters to reflect the shifting relationship between the gods and those who worship them is extremely clever. Striking that balance between magical realism and slice-of-life romance seems effortless for Simon.

The final image of Simon’s Aquina bathing in the sea is recapitulated by the title page of the next story, Anna Haifisch’s “A Proud Race.” It’s typical of Haifisch’s surreal and absurd storytelling, as running commentary at the bottom of the page tells of the triumphs and tragedies of a herd of ostriches. From sexy dances to exciting races to watching out for leopard attacks, Haifisch drily narrates these birds and the absurd existence she imagines for them. Working with purple and orange as her main colors only adds to the silly strangeness of this piece.

Keren Katz is an appropriate choice to follow, given her non-linear storytelling style that compresses movement to form unusual compositions on each page. The narrator of “My Summer At The Fountain Of Fire And Water” has a crush on a man named Yonatan who has a stall at the flea market that pops up around the titular fountain. The entire story is a swirl of fabric, as blankets formed the stalls, draped over wood framework. Like much of Katz’s work, the movement here is akin to a complicated, abstract dance between characters and objects in a two-dimensional space. The furtive attempts at the narrator expressing feelings for Yonatan are told in parallel with the images, working in concert with them without trying to make sense of them.

The anchor piece of NOW #3 is Roberta Scomparsa’s fascinating slice-of-life look at incipient sexuality in a pair of sisters at the beach with their mother. TItled “The Jellyfish,” this 33-page story features pre-teen Irene and young adult Elisabetta. The latter is obsessed with her boyfriend and the former has that pre-teen wish to be older. That manifests in her wanting to wear a bathing suit with a top like other girls her age, because going topless is a signifier of being a child. Scomparsa amusingly explores the different shapes and kinds of bodies, with Irene’s mom scoffing at a nearby older woman with fake breasts. She also explores the intersection of fantasy and reality, with Elisabetta recalling (or simply fantasizing) her boyfriend pissing on her and interspersing that with her mom washing apricots, as well as eating apricots while imagining her boyfriend eating her out. Both girls are in their own private worlds, one that Irene violates in the end by looking at her sister’s phone, where she sees a nude that he had sent her. It’s a moment where a line was crossed, not only in terms of privacy but also of innocence, where her teasing banter with her sister about her boyfriend suddenly feels a lot more real. The slightly lurid colors Scomparsa uses only adds to that fantasy quality of the story, where the idea of sex is larger than life.

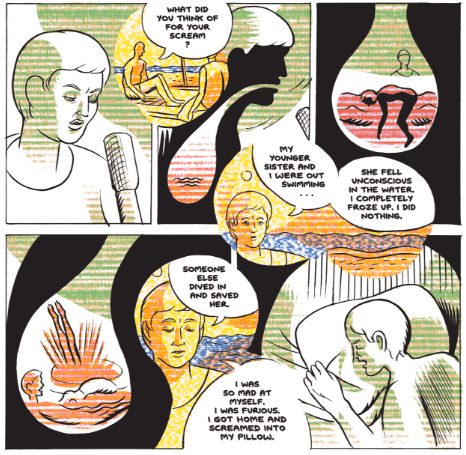

Dash Shaw’s “Crowd Chatter” plays on that bright, slightly fantastic use of color in a story about a sound designer for commercials trying to get his subjects to give him a good scream for a commercial involving a protest scene. Shaw balances the clinical aspects of making the commercial with how the protagonist asks his subjects to imagine something personal and awful in order to get what he wants. It’s all in service to get a beach weekend with his kid, bringing up the idea of having people you use and people you love.

The visceral character of Shaw’s cartooning, mixed with an entirely different element, is repeated in a different way in Eleanor Davis’ “March Of The Penguins.” The story starts as a procedural about a crime sanitation clean-up crew at a job site, in a house covered with blood after a murder. The manager of the crew has to comfort a new member after he gets sick. Then the manager goes home to have sex with his girlfriend, and he has a very specific kink: watching the movie March Of The Penguins and getting off to a scene where a seal eats two penguins and two other penguins die. It’s done in black & white, with red splashed in for blood and a blue wash used for the television. Davis has a way of homing in on kinks in some of her comics in such fine detail that one doesn’t know whether to squirm in discomfort, howl with laughter, or both.

Marcello Quintanilha’s “Sweet Daddy” is a different kind of fantasy, as the crisp black & white linework follows an old man who’s been in an accident and is slipping in and out of consciousness. The story slowly unravels the details of his life, his abusiveness, and his relationship with his adult daughter, whom he imagines to still be six years old. It’s a story of a monster defanged, more pathetic than anything else.

The anthology concludes with three short, odd, comedic pieces. Jose Ja Ja Ja’s “Grand Slam” crams 24 panels on each page as it slips between a televised tennis match and a violent tableau in a home. Nathan Cowdry’s strip is about a baby and a cat man describing their mutual fear of vaginas. Noah Van Sciver’s “Wolf-Nerd” is typical of his short humor pieces, in which a nerdy creative type not only gets his comeuppance in the story he writes, but also in real life. Much of the last thirty or so pages feels thin compared to the stronger work by Davis, Simon, Katz, Scomparsa, Shaw, and Passmore in particular. It felt like the back half was lacking one more anchor piece for the shorter pieces to play around it. That said, Reynolds’ willingness to experiment and bring in so many new cartoonists led to some bold, interesting choices. By eschewing a regular lineup of artists and continuing features, NOW has proven to be highly unpredictable in its first three issues.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply