NOW #8 was one of its best issues from top to bottom, and that’s a testament to editor Eric Reynolds assembling an issue where every single story was both entirely within a fairly traditional comics tradition but none of them were stylistically similar. If these stories share something in common, it’s that almost all of them are self-examinations. Some of the stories look back, often with regret and wistfulness. Others are taking stock of their lives as they are now, sometimes wondering how they got there. In some stories, this involves a feeling of being trapped or stuck, and in others, one can feel the gratitude for a particular moment in time from youth.

The cover is an oddly delightful piece from Al Columbia depicting two tiny people riding a lizard in a chair that’s strapped to it. They’re in the middle of an adventure, pausing for just a moment. There’s a sense of wonder here that’s different from much of Columbia’s work, and no feelings of dread. It’s an interesting harbinger for a volume that avoids some of the more horror-tinged stories that were featured in earlier volumes of NOW. However, Reynolds, as always, starts with a short, trippy piece from Theo Ellsworth. This is a study of a creature in quiet, calm repose.

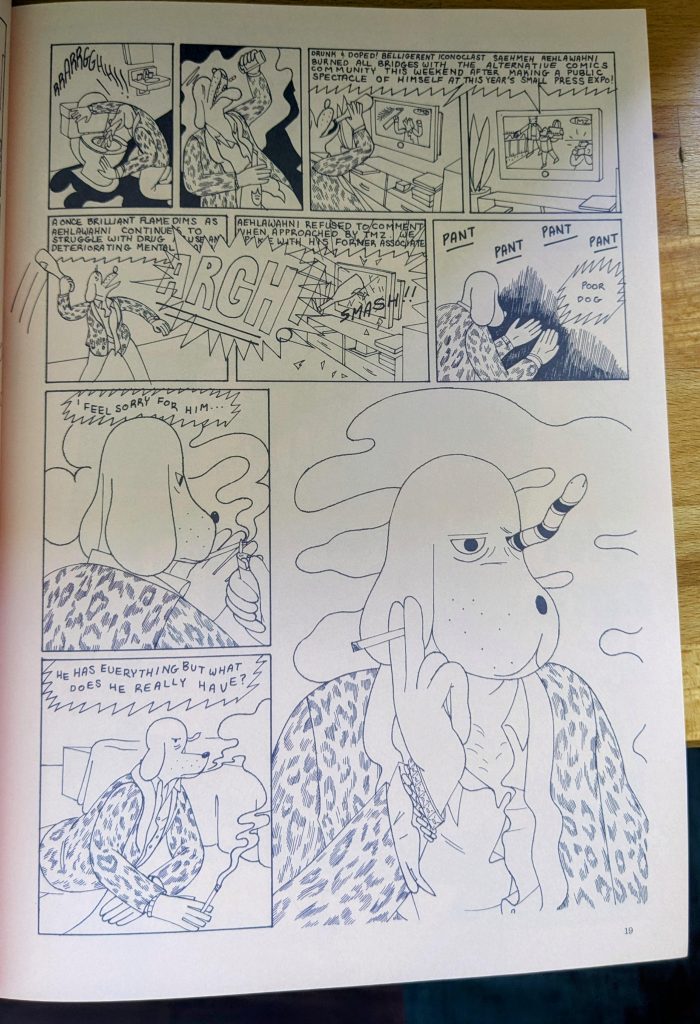

All of this is the calm before the storm for two absolute comics tours-de-force. The first is from Canadian cartoonist Sami Alwani. It’s at once relentlessly and hilariously self-referential, filled with lots of inside jokes about comics, and also intensely personal and intimate. “The Misfortunes of Virtue” is at once a howl (literally, at times, since his stand-in is an anthropomorphic dog), a meditation, and a series of expertly-deployed barbs aimed at himself and the art world. It’s also an intimate look at his life as a queer man desperately looking for connection, even as he has to navigate being objectified as “exotic” because of his Arabic heritage. His line is loose and playful, veering from naturalism to the grotesque on a dime. The story is an examination of fame, his desire for it, and his total revulsion toward the idea of actually achieving it.

The second is an epic story from E.S. Glenn featuring several comics-within-a-comic as his stand-in character is an artist turned assassin. This is also filled with a number of art and comics world inside jokes, especially as it ruthlessly satirizes the frequently racist imagery found in “classic” comic strips. Rendered in a classic ligne claire style and brightly but tastefully colored like an album from Herge, Glenn brilliantly mashes up gangster stories, magic, funny animals, dream comics, memoir, and so much else. As a Black cartoonist, he has a lot to say about the racist imagery common in comics through his stand-in, a cartoonist named Philip T. Crow. Mixing points of view liberally as the narratives of various comics being read transform into the narratives on the page, the actual hitman plot is a steady presence throughout the story. The magical elements fit easily with the anthropomorphic depictions of characters as well as the content of the strips. Glenn delights in crossing narrative steams, as the story of the daughter of a dead mob boss who’s just been released from prison crosses that of the killer in dreams, where they realize they are each other’s muse. Panels turning into torn photographs represent trauma in an incredibly clever way. The story, titled “The Gigs,” reveals something new with every reading.

After the intensity of Alwani’s story and the visual pyrotechnics from Glenn comes Veronika Muchitsch’s “I, Keira.” Without using a line of any kind, Muchitsch, instead, uses colors and shapes in a calming, soothing manner to tell the story of the titular woman who offers to live in an Ikea-like furniture store. The ability to escape life, the opportunity to live in an ordered environment, and the freedom to daydream are all reasons why Keira choose this life…until she remembers that “I find myself at the bottom of a container.” The flatness of the art reflects the lack of affect in the character, especially her own complicity in taking on the unexamined quality of furniture.

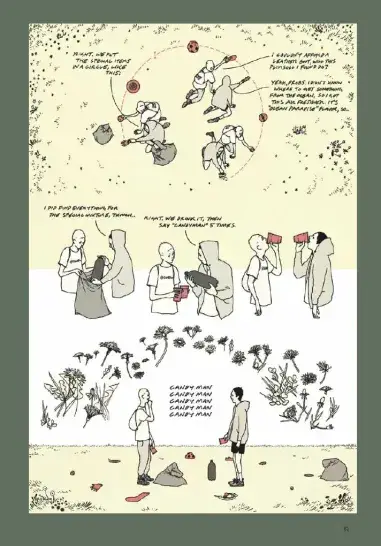

Of all the stories in NOW #8, Henry McCausland’s “Garden Boys” is the one that’s most in the moment. Two teens go through an elaborate set of rituals that have an increasingly fabulist bent. There’s a slightly disheveled quality to McCausland’s line that reminds me of Anders Nilsen, from the simplified line for the characters to the detailed drawings of background grass and detritus. Starting with a ritual to spread their graffiti across an abandoned building, it extends to the boys finding “treasure” in an abandoned yard, jumping on a helicopter, and then turning into the sun and Optimus Prime, respectively. All of that fabulism aside, the most magical moment is when they nail a crossbar with five consecutive throws, leading to a joyous victory dance and embrace. McCausland makes extensive use of the DeLuca effect throughout the comic, and this is one of the most effective instances of it. Their elation is coded in red in a comic that mostly has a green wash, and it’s drawn at a smaller scale than most of the other scenes. It’s a moment of intimacy, unplanned in what are otherwise meticulously-planned fantasy activities.

Italian artist Zuzu’s story “Red” is similarly about two teens in a formative moment. While it takes place in the present, one can’t help but feel that the shift inherent in the story feels like someone trying to remember a crucial time. Zuzu’s line reminds me a lot of Gipi’s, in that there is a highly exaggerated sense of the grotesque with regard to certain facial features, with noses and ears looking clownishly big and discolored. It’s a kind of shorthand for teenage awkwardness. The story follows a boy and girl who share a lot of intimate, pre-sexual moments until the girl’s mom declares that they are now “practically cousins” because the boy’s mom and her uncle are now involved. It’s the kind of off-handed, meaningless statement by an adult that has a profound impact on children. When she tells him they can no longer play the game of “mom and dad” anymore (which involves her lying on top of him, with both clothed), he asks for one last time. Here, in a story that otherwise has a cool blue wash, a brick-red wash represents pure desire. The final page is entirely red, a final fade-out for a desire that’s now forbidden.

Noah Van Sciver’s “Saint Cole” is the sort of funny and wistful story about the practice of cartooning that he seems to be doing more of these days. The present-day story is about a failure of a signing in France. It also flashes back to the beginning of his career, when he was working in a Subway and self-publishing his first comics. Van Sciver’s comics have always been about the indignity of the artist’s life and the small humiliations that must be endured, but it’s also been maximally played up for laughs. This story is really one of gratitude, detailing a fun experience in the Catacombs of Paris, meeting that one big fan who makes it all worthwhile, and reflecting on what success means. Van Sciver is such a student of cartooning, absorbing so much from a wide swath of masters, but I really see him being in the continuum of Harvey Kurtzman-influenced cartoonists above all else. The Will Elder-style “chicken fat” that’s always been a cornerstone of his work has been polished and carefully incorporated into the larger narrative. His storytelling and attention to detail are both rock-solid.

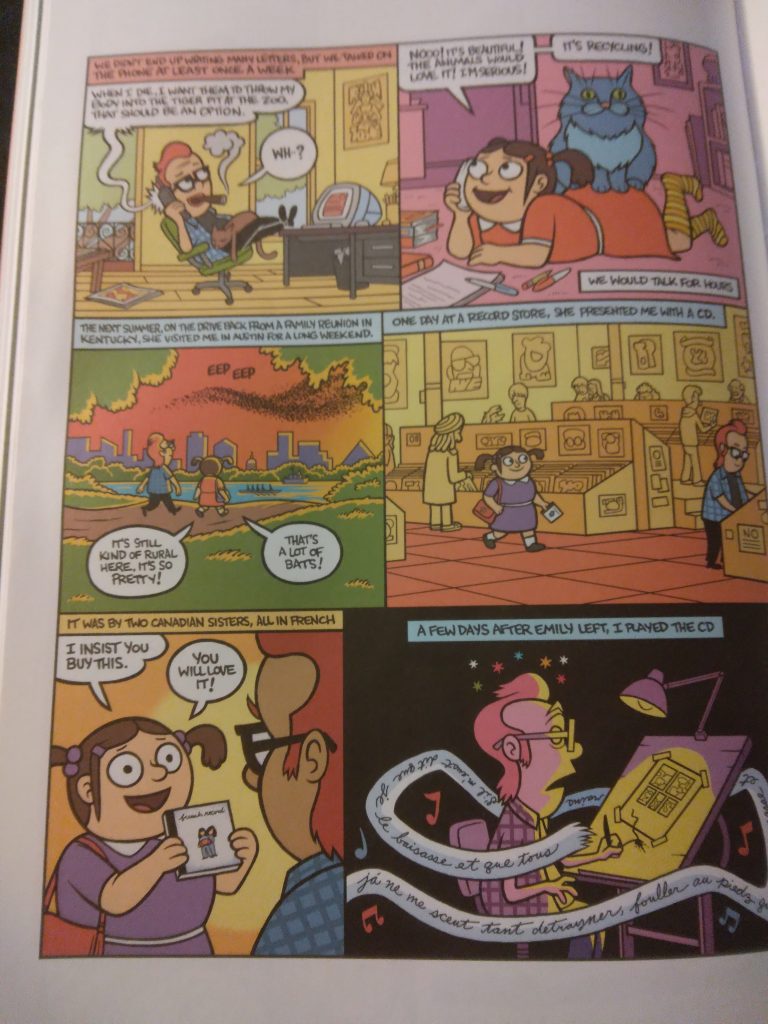

Another excellent craftsman who’s made NOW his new home is the great Walt Holcombe. “Cheminant Avec Emily” is yet another memorable entry in his series of highly personal stories he’s been publishing in NOW. His years spent in animation have only made his storytelling, character design, and use of color so much more highly refined than his early work–and that already had a high level of technical excellence. Every line and detail is meaningful in this heartfelt story about a life-changing friendship, the music shared that was equally impactful, and the sad way in which it ended. Like many of the other stories in this issue, Holcombe really takes stock of mistakes he’s made and the progress he’s achieved with regard to his mental health and past traumas. The end result is a mea culpa and a gift.

Maggie Umber is another regular in NOW, mostly producing mood pieces that emphasize emotion through oblique imagery. “The Intoxicated” is about a party and the ways in which a hook-up literally destroys identity in the form of obliterating the lines of faces. The overwhelming feeling of regret for impulsive action pervades this story.

Finally, Tara Booth’s scrawled line and splattered watercolors, often used to convey humor, here depict heartache. A friend gives her a pie for her birthday but wants to be mindful of Booth’s character’s binge eating. She assures them it’s fine, they both eat a piece, and the cake is thrown away. Later, a desperate Booth fishes the cake from the garbage, now coated with hair and dirt, and sweatily scarfs it down. The final image is one of regret, to be sure, but it’s an almost indignant regret, as though she can’t believe it happened.

A lot of regrets depicted in NOW #8 are like this. It’s a feeling of regret but being trapped in a set of circumstances or behaviors that lead one back to this feeling over and over. Whether it’s Muchitsch’s Keira trapping herself in the furniture store, Alwani’s character feeling trapped by the desire for control, or the implication that the characters in Umber’s story repeatedly acting out this dance of intoxication and shame, there’s a sense that there’s no escape. At least, there’s a sense in some of the stories that they’re not willing to find a way to escape the cycle. For others, like McCausland, Holcombe, and Van Sciver, their stories reflect a more affectionate look at past mistakes and treasure key moments that are gone. The gestalt is an issue of NOW that’s much more intimate and personal than the stories in recent issues.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply