NOW #7 was published in 2019, and it’s an issue that’s filled with a lingering sense of dread. Not quite in the sense of horror as in #6, but a general sense of disquiet, waiting for the other shoe to drop. It’s an issue filled with regrets over bad choices that are too late to fix. The stories also have themes where people are trying to create art in the face of this anxiety, with some more successful than others. It’s a tight 110 pages and there feels like there’s a lot less filler this time around. It helped that Reynolds went with somewhat more traditional cartooning in this volume, and it further helped that he had cartoonists with highly stylized art, like Chris Wright, Kate Lacour, and James Romberger. This issue of NOW simply flowed better than the previous issue.

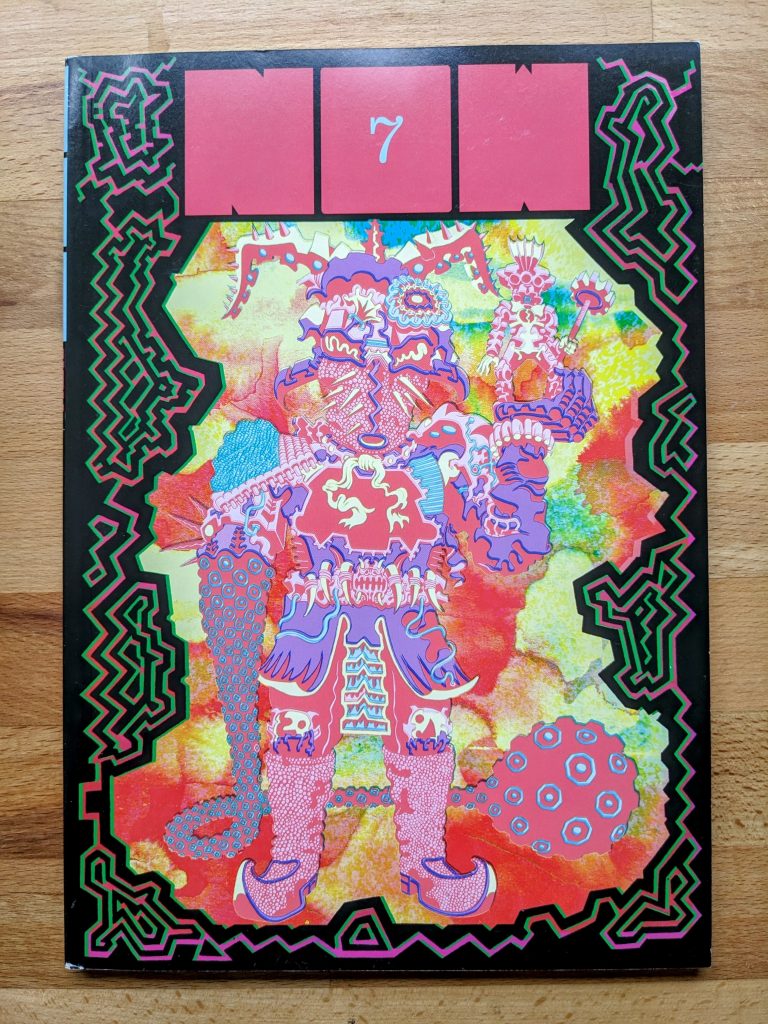

Will Sweeney’s menacingly psychedelic cover, titled “Reptilian Enforcer,” is a harbinger of this dread. Something strange and inexplicable looms over you, as you await something bad. Theo Ellsworth’s “Yellow Slip” is an unusual comic for him. While done in his usual dense, distorted, and colorful style, the story is explicitly about work anxiety. An employee late for work loses control of his comically tiny vehicle, gets into an accident, and then literally hides in the bushes. Meanwhile, his boss is waiting to give him a dreaded “yellow slip,” with a “horrible, baby eating grin on his face.” There is no resolution to this strip–just disaster and anxiety.

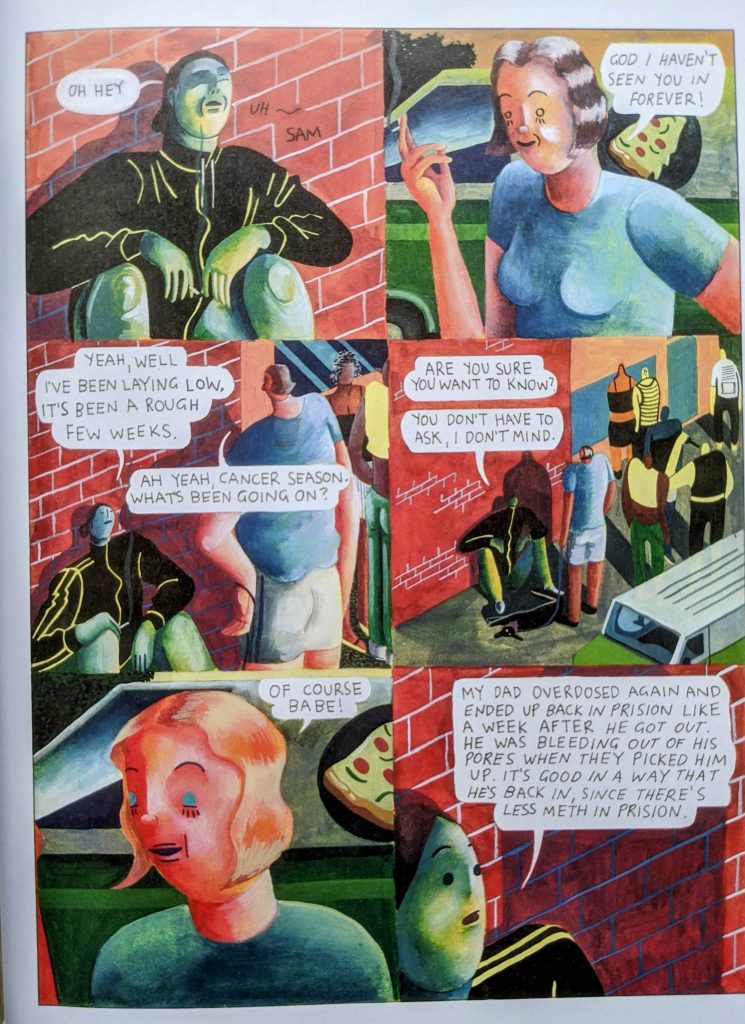

Tommi Parrish’s lushly-colored story “Sasha” is a vivid and hilarious illustration of social anxiety. The titular character just wants to find a way to connect with others, tries as hard as possible, and is stymied at every turn. It starts with a dog growling at them. A friend spots them on the street and is only interested in the most banal of conversations. When Sasha opens up about their dad overdosing and going into prison, their friend says “I totally get it. When Trump got elected, I basically wanted to die too.” Things get worse at a house party/concert. Sasha is naturally the first person there and endures a hilariously awful bit of existential spew from a singer/songwriter, with the further indignity of a couple making out next to them, ignoring their existence on the couch. The story ends with Sasha trying to tell their woes about being hassled by cops to a guy who just wanted a light. What’s interesting about this story with regard to Parrish is that they tend to write stories that are painfully intimate, with difficult emotions being processed by both characters. Here, Sasha is stonewalled at every turn as they are desperate to communicate, but no one is interested in engaging with someone else’s problems.

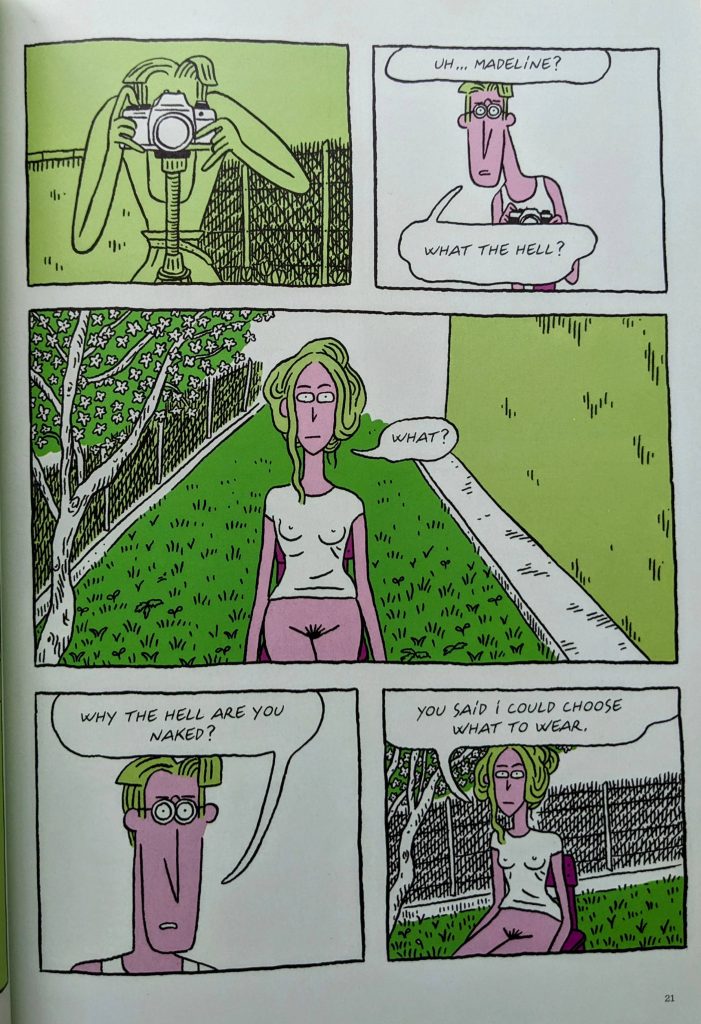

Even a total change in visual style keeps up this feeling. French artist El Don Guillermo’s “The Cherry Season” is drawn in a cartoony style that’s not unusual in the Franco-Belgian tradition, and exactly what kind of story it is is rather slippery at first. It’s about a photographer named Robert and his fiancee’ Madeline, and it’s about a thorny and bizarre experience he has trying to do a shoot with her in their backyard. Madeline inexplicably comes out wearing only a shirt, which sparks an argument with Robert, who has other ideas. Things get weird when their elderly neighbor brings them cherries and suggests knocking over a chair to add tension to the shot. She’s also completely nonplussed by Madeline’s nudity. Things get even weirder when it’s suggested that their neighbor (whose first love was a photographer named Robert) is actually Madeline from the future, and she recreates the shot that Robert is about to take of Madeline in her own backyard. The time loop suggests, among other things, that Robert and Madeline’s relationship won’t last, in part because he doesn’t want to listen to her. This feeling of dread that pervades the issue is very much tied into this idea of not being heard, despite one’s best efforts.

James Romberger explores this idea as it pertains to mortality in “Au Jour D’Hui.” The title refers to the French expression that essentially means “today,” and it’s about a day at the beach, sketchily drawn with a powerful sense of immediacy. A man comes out of the surge, collapses, and dies. The day at the beach goes on, as his death is simply shrugged off the way Tommi Parrish’s characters shrugged off Sasha’s pain. The spareness of Romberger is followed by the dense hatching and crosshatching of Chris Wright, who writes about a series of transactions. His comically grotesque figures have an almost Cubist quality to them in terms of the way their bodies twist and distort at strange angles. Some of the transactions are violent, some are commercial, some are romantic–but all of them have a sense of desperation.

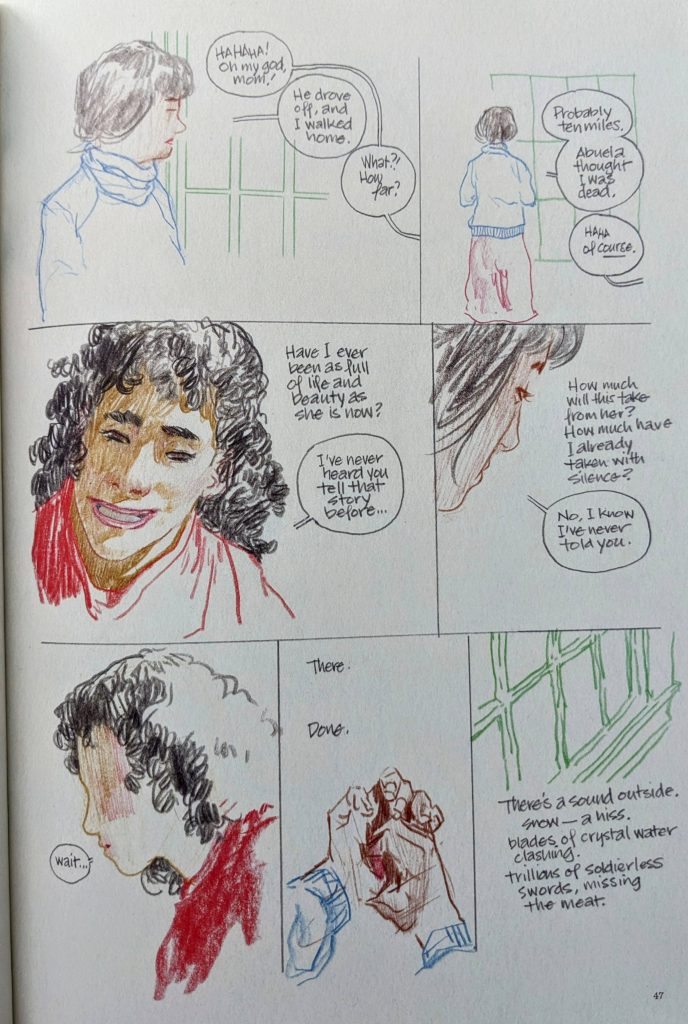

The height of Romberger’s absurdity can’t really be topped, so there’s a shift to Kurt Ankeny’s story about a mother who springs the truth of her father’s identity on her college-age daughter. Just as her daughter is forming a community and friendships, the mother is choosing to isolate herself in a cabin, refusing to nurture anything else. In a story told against a wintry landscape, his delicate use of colored pencil adds depth and weight to pages filled with white space. The daughter attempts to contact him, then chickens out before she meets him. The story is fascinating because of the way it depicts memory as such a capricious thing. The father’s memory of his final, screaming argument with the mother are quite different than hers, and his feelings about it all are also different. The mother abruptly changes the nature of her relationship with her daughter with one capricious confession, in part because she’s tired of being a mother. The daughter reflects on her own choices that she’s going to have to make. It’s an emotionally complex and exquisitely-drawn story that feels like the anchor piece of this issue of NOW.

Maria Medem’s “Exercise 08” feels like a peek behind the curtain of reality, as what appears to be godlike beings practice at preserving and protecting creation from threats. Even the abstracted character design and color scheme that ranges between almost painfully bright and absolutely dull, is completely unlike anything else in this volume. Kate Lacour’s take on the story of Pinocchio emphasizes the struggle with the concept of free will. Born in pain, Lacour emphasizes the little wooden boy beset by temptation, with his creator being faceless. There’s no dialogue, but each panel has a ribbon with a caption, dramatically emphasizing each scene as though it was a Station of the Cross in Catholic iconography. No story captures the lingering sense of dread featured so prominently in this issue as this one. The delicacy of her line, combined with grounding elements like hatching and cross-hatching, puts the characters, their feelings, and their perils front and center. The final image feels like a cruel joke, but it’s one that makes sense: we are never free of our strings.

Keren Katz’s “The Boy Who Wanted To Laugh” is the other anchor piece of the issue. It echoes the themes of Lacour’s Pinocchio piece, as well as the general sense of anxiety, paranoia, and things left abandoned, undone, or done incorrectly. Katz’s drawings of clutter are interspersed with figure drawings posed in awkward, angular, and twisted positions, which only heightens the sense of discomfort and unease in reading this story. The issue ends on a lighter note (per usual in NOW) with short, comedic stories. Even here, in stories like Nick Thorburn’s “Fred Is Fried,” the stories are about things going horribly wrong and bad choices. In this story, marked by grotesque and cartoony art, a guy goes to a place that seems like part drug dispensary and part social event to get something for his back pain. He takes too many licks from a rock called “tribble,” and it induces horrifying, hilarious, and ego-destroying hallucinations. Noah Van Sciver’s story about a self-identified “punk” who talks young Noah into videotaping him on a skateboard is a hilariously icon-destroying piece of comedy. Finally, Nathan Cowdry’s fake PSA from a seal named Sammy veers from a pedantic bit of social commentary to an absurd set of references to Navy SEALS, Osama Bin Laden, and government-approved propaganda.

I always got the sense that Eric Reynolds uses a fairly intuitive approach when it comes to editing NOW. There are some obvious pieces from bigger names like J-C Menu that get consideration for an issue, but to some degree he’s also at the mercy of the material that is sent to him as he’s putting an issue together, resulting in a poor fit for an issue’s flow or just outright filler. Reynolds has always been resolutely against formal theme constraints, but his looser themes seem to suit his personal aesthetic as well as a more fluid and coherent reading experience for the reader. The paranoia, anxiety, and alienation shown in NOW #7 make for interesting connections and certainly seem to be an accurate read on the general cultural zeitgeist.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply