Eric Reynolds, of course, is the editor of the Fantagraphics anthology series NOW. One of his favorite cartoonists is Al Columbia, a horror artist known for producing extremely disquieting work that rarely had to rely on extreme gore or violence for it to be terrifying. Columbia contributed a little to NOW’s predecessor MOME, and it was the shift in tone in the back half of that anthology’s run that made the disquieting touches he added seem fitting.

The sixth issue of NOW doesn’t have any pieces by Columbia, but his influence on Reynolds’ tastes couldn’t be any more apparent. This is as close to a straight-up horror anthology that Reynolds has published. That horror is often in the guise of what seems to be lush, verdant growth. However, death, decay, and chaos lurk everywhere in this issue, although no two cartoonists approach it in the same way.

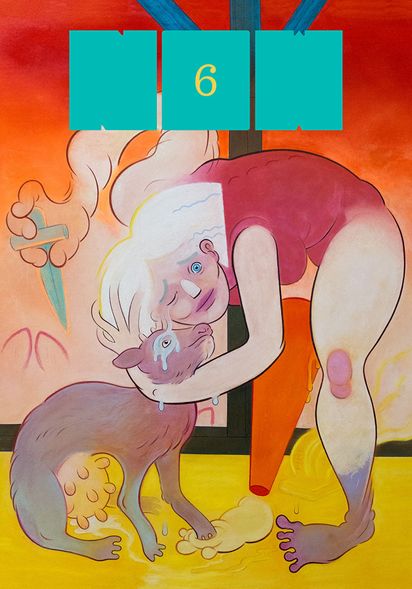

Koak’s cover, titled “Jenny Goat,” initially distracts the reader with soft, pleasing colors and looping lines, until the grotesque, absurd qualities of the person come into sharper focus. The woman on the cover has a traffic cone for a leg and a dagger held in a splayed, twisted arm that’s about to stab the goat that she’s trying to (pretending to?) comfort. It’s disconcerting, off-putting, and bizarre, and this sets the tone for the rest of the issue.

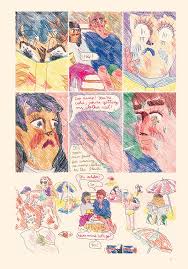

Theo Ellsworth’s opener is about the horror of facial recognition software with regard to how police might use it. This paranoia is deflected by his intense, cartoony mark-making, a style that’s carried over in a different way by Mariana Pita in her entry. This story that starts at a beach is on constantly shifting narrative sands, moving from what appears to be an almost childish colored pencil scrawl in its observation of a couple at that beach to their bizarre, enigmatic job that requires them to put on uniforms and magically ride on tree branches to create designs in the clouds. Once again, surveillance by their mysterious employer is simply assumed as the man and woman bicker and banter; only their cat seems truly free to come and go.

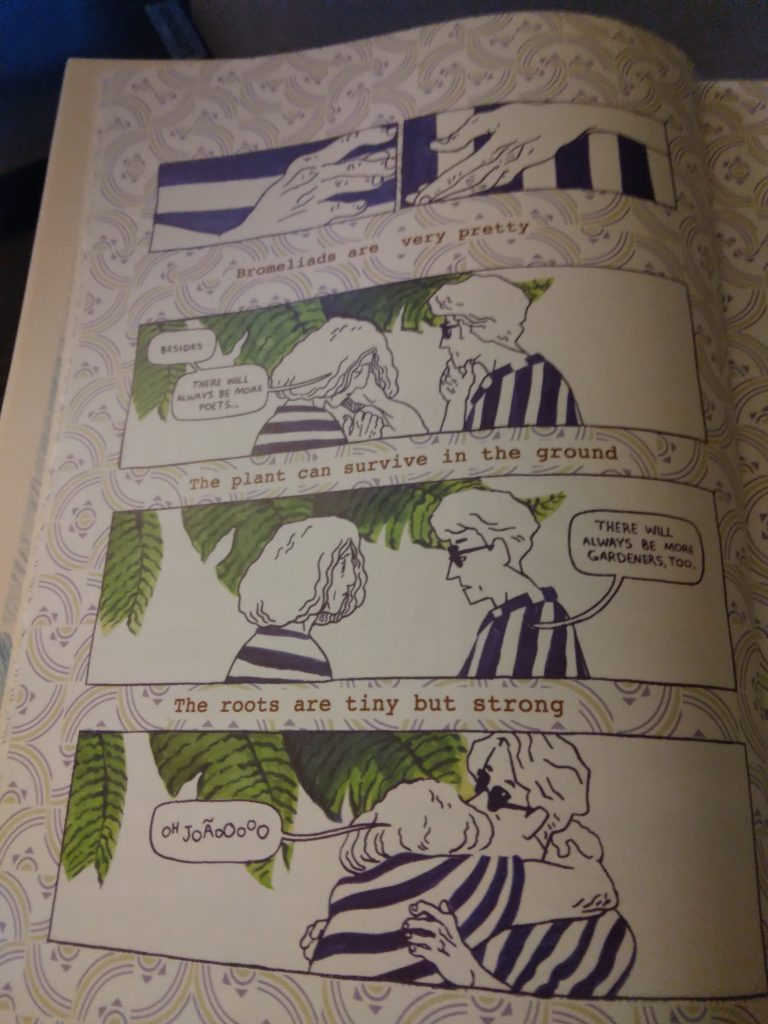

M.Dean and C.J. Aguilera’s “Bromeliads” is about a young woman and her friend (lover?) in conflict about her moving away from her literary career in New York in favor of tending flowers in Florida. As they struggle with this, there’s a parallel set of narrative captions that seem to comment on the flowers, but not the action itself. The narrative talking about the flower blooming and replacing the original is especially pointed, implying that this pretty flower is going to outlive her friend/mentor/lover. That theme of sinister lushness continues in the green scribbles of Amandine Meyer’s “Shivering Story,” which is about the ways in which the very form, the very stuff of life that makes up two girls shifts, unravels, rewrites itself, and is swept up by larger forces. There is constant movement and mystery in this wordless story, as it ends in an enigmatic, majestic room. Here, there is terror in the mystery of life itself, but the girls have no choice but to go along with it and allow themselves to be transformed.

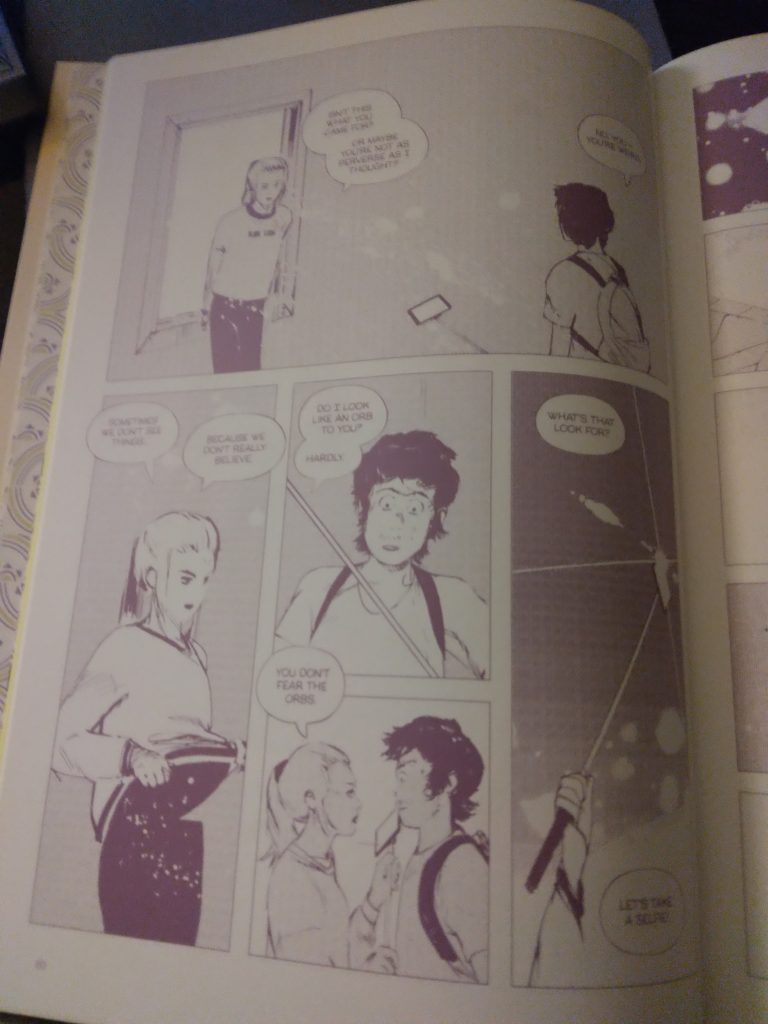

That sense of being swept along by forces one doesn’t understand is also the key to Aseyn’s frightening story “Orbs.” The line looks a bit like CF’s erasure technique at work in terms of the fragile quality of the line along with some dense zip-a-tone effects, all with a violet wash. Set in California, it seems to be like any number of hipster, slice-of-life stories about desperate people at first, as it follows a young woman named Claire and her narrative about escaping to California and leaving things behind. She takes a shine to a ghost-hunter bro in a diner and butts her way into going on a scouting mission for a potential haunted house video. When he tells her that ghosts appear as orbs of light, she reveals her true, terrifying nature–even as she continues on her narrative of regret. Reynolds seamlessly follows this up with a short story from noir-inspired cartoonist Tim Lane, in a tale about two guys on the run at a drive-in theater in the 1950s. As they worry about a particular guy having followed them in, a mysterious woman walks up to the car, and one of the men simply disappears with her. It’s unexplained and contributes to the all-around feeling of dread that underlies each story in this issue, in one form or another.

The transitional piece is a comic from Jose Quintanar that features a 4 x 6 grid on every page, meant to approximate the experience of watching TV and flipping channels. The fake violence flips into footage from a rocket launch akin to the space shuttle Challenger exploding, with the drifting wreckage creating cognitive dissonance. The drawing is spare and the colors garish, approximating the banality of the experience. It’s a comic about isolation. Veronika Muchitsch follows that with a carefully arranged series of drawings adapted from YouTube Mukbang videos Mukbang features individuals filming themselves binge-eating at home and talking about it (frequently in a gentle ASMR tone) to their audience. Muchitsch creates a sort of sequential order from several different videos, each of which is surprisingly confessional in terms of each person’s sadness and sense of isolation. At the same time, it’s a performance that captures the essence of parasocial relationships, ones where there seems to be a level of intimacy that’s not really there. Muchitsch uses colors so bright and a line so thin that it’s almost unpleasant to read.

Disa Wallander’s open-page format strip consists of a poet reading a non-poem to her audience and continues this entirely conceptual reading with the idea that everyone is a poem. It finishes with the reader being allowed to read their own poem and her listening; of course, it turns out to be “gross.” It’s a predictable gag that is more interesting as an interstitial piece than something that’s interesting on its own, but the red wash of the story is a nice contrast to Julian Glander’s digitally-rendered 3D piece about going to a museum. This is another piece about alienation and performance, both from the patrons and the art meant to entertain them.

Jesse Reklaw’s “Cat-A-Tonic” is an odd departure from that story, as the transition from the other stories feels a lot looser and less conceptually sound. As pleasant as Reklaw’s entry about cats and the spirits that one vomits up is to read, I don’t think it makes a lot of sense in the context of this issue. Zohar Lazar’s piece feels like something out of Heavy Metal instead of NOW, complete with tree monsters with hick accents, naked ghosts, and random violence. It’s an inessential lark that fills out the horror component of the issue (as does Reklaw’s strip, to some extent), but it’s not close to being as compelling as the strips in the first half of the issue.

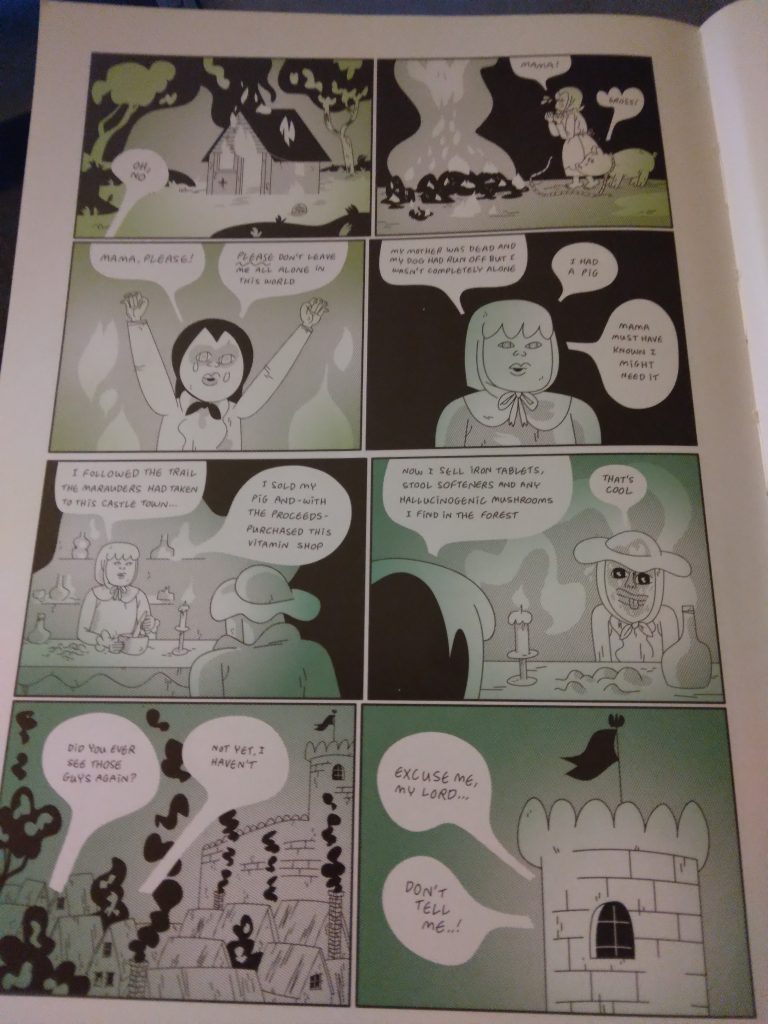

All is forgiven with the final strip in the anthology, Steven Weissman’s hilarious, horrific masterpiece “The Bastard Princess.” Weissman is an artist whose work took me a while to appreciate. His characters (usually kids) have a casual sense of insolence and antisocial behavior so extreme that it can be off-putting, but further readings reveal the ways he is slyly appropriating and satirizing classic cartooning like Charles Schulz’s Peanuts. This story is a flip send-up of fairy tales and their frequent use of casual violence and rape as part of the landscape of the story. This story is about a witch who helps the king with his impotence problem (he’s not actually interested in women, as it turns out), only to get raped and impregnated by him. She curses his seed after that and all of his children die after childbirth, so the king comes for his bastard son. The witch transforms her son into a girl and then turns the dog into a boy. The king comes along, kills the witch, and takes the dog-boy to raise as his son. Well, he may look like a boy, but he acts like a dog: stealing food, being aggressive, and using the world as his toilet. Weissman takes a ridiculous story and then puts in a clever plot twist with a final gag that is unbelievably mean and yet spot-on.

The first half of this issue is as good as anything that Reynolds has ever edited, but the back half just feels like filler that doesn’t cohere, with the exception of Weissman’s story. It had its own rhythms as a horror story, even if Weissman wanted the reader to laugh at its every grotesque twist. This is partly a reflection of NOW having a certain page count per issue (about ~120 or so pages) and the need to fill it out a bit. In this case, the stories he used to fill out the back half felt like material that should have been in another issue, mostly as interstitial pieces. None stood out on their own, nor did they even provide an interesting counterbalance to this issue’s horror theme. Editing an anthology is hard work and sequencing it is even harder, but Reynolds just didn’t have quite enough to work with here to make it all fit together.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply