When I wrote two weeks ago that the next decade looked to be more gruesome and frightening than the last, I wasn’t expecting that prediction to come true immediately; but here we are, on the precipice of war with Iran, and I’m reviewing Eleanor Davis’ The Hard Tomorrow, published by Drawn & Quarterly in 2019. Six months ago, I would have told you that The Hard Tomorrow was a bleaker vision of an American life than what currently exists. Now, I’m not certain I can say that with a straight face.

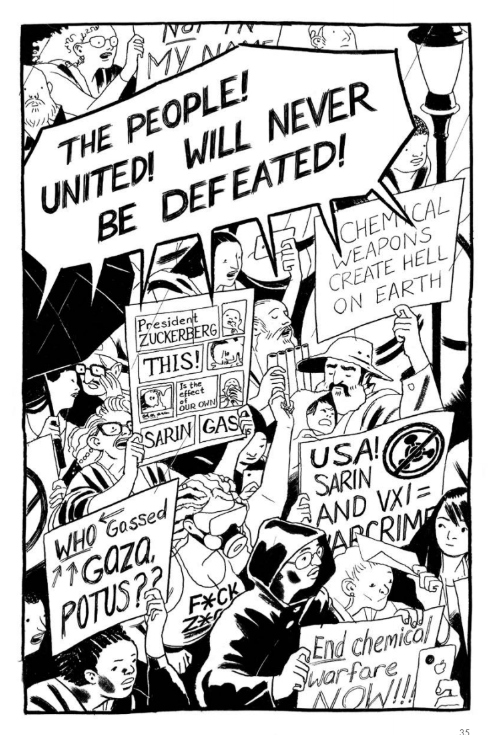

The Hard Tomorrow doesn’t neatly fit into any category or genre; it defies expectations. The best way I can describe the book is to say that it’s about the complexities of human relationships and human choice. In this work, Davis examines the current political and global climate through a somewhat parallel universe. Mark Zuckerberg is president. The United States has a “Chemical Defense Program” and has been gassing the citizens of Palestine. There’s a predicted complete oak tree extinction by 2030. But this isn’t more dystopic than our current moment, not really. If you think otherwise, you probably just aren’t paying attention. The Hard Tomorrow is also something of an artistic transition for Davis – this is one of Davis’ first long-form stories, and, to a certain degree, it feels like a short story that has gotten a little overgrown.

But complicated work exists for complicated times, and no graphic novel I read in 2019 was as nuanced as The Hard Tomorrow. The book is centered around Hannah Plotkin, a Jewish anti-war activist and a home health aide, and her ne’er-do-well partner Johnny who is supposedly building a house so they don’t have to sleep in a truck during the winter. Hannah’s world is going off the rails, but she finds shelter in a community of activists. She and Johnny exist living a life on the outskirts, where Johnny sells weed and propagates food seeds.

I’ve been reading Eleanor Davis’ work for years, and one of the first things I noticed in The Hard Tomorrow is the change in Davis’ illustrative style. Davis’ cartooning over the last decade has largely been in service to some universal ideal. Her characters were relatable but sometimes generic. Her illustrations were beautiful but sometimes simple. All that has changed with The Hard Tomorrow. Here, her characters are detailed; they feel real, more human than ever before. Davis has eschewed an idealized, normalized beauty for a more specific and human beauty.

We see that specificity in other ways; The Hard Tomorrow earns most of its narrative heft through its true-to-life relationships. In fact, it is the nuance inherent in these relationships that is the driving force of The Hard Tomorrow. We see this in simple ways, like the way Hannah takes care of Phyllis, an elderly woman who suffers from dementia. Hannah cares for Phyllis with affection, like a grandmother, but Phyllis is antisemitic. We see that nuance in more complex ways with the two major relationships the main characters have outside of their marriage. Johnny hangs out with Tyler, an off-the-grid survivalist who helps build the frame of the home Johnny is building, but Tyler is also a source of male aggression and misogyny that Johnny has to deny. Gabby, a queer naturalist who works with Hannah at Humans Against All Violence, is one of Hannah’s best friends, but their relationship has gotten emotionally tangled and messy, in ways that both women haven’t really expected.

The Hard Tomorrow is also a study in contrasts. There are idyllic scenes where Gabby and Hannah forage for mushrooms and wild grapes, and at times the world seems almost Edenic. But it’s a world that is falling apart due to human action. Communities are being built by people trying to build a better future, and those communities are crushed by police violence and fascism. Hannah gets treated nicely by a female cop when she runs a stop sign; this officer later attacks her at an impromptu rally.

The contrasts don’t just exist in the narrative; Davis’ command of illustration and composition are in full display in this comic. Despite the decay of the natural world, Davis displays it as open and inviting, full of splendor. The cityscape much less so, full of dark inks, sharp angles, and the sense that it’s all about to topple down on you. There’s a scene where Johnny races against an oncoming storm after something terrible has happened. The rain is pouring in, he’s having a panic attack, and he’s missed a lot of phone calls from Hannah who is in an equally horrible state. My own pulse starts to quicken, I start to feel nauseous. It is in scenes like this where the power of the form truly gets conveyed.

The more I read and think about The Hard Tomorrow, the more I come to realize that these contrasts are the heart of the book. If the future is a shiny nickel, then hope is one face, and despair is the other. It seems to me that much of The Hard Tomorrow is centered in this coinflip. But perhaps calling it a coinflip does this moment a disservice. Despair can be beaten back as long as we have a choice. Perhaps Davis is asking us to make our choice.

Personally, I’m primed to like The Hard Tomorrow. It grapples with a lot of questions I’ve been having lately. What does it mean to think about having a baby in times like these? How are we supposed to function right now as climate change races towards us? My wife and I have been talking about having a second child. But, like Gabby says, why would anyone want to have a kid right now? It’s a question I’ve been struggling to answer.

Having The Hard Tomorrow to sit with during this interstitial moment, where nothing seems certain and everything seems to buzz with complexity and violence, has been something of a comfort. Davis doesn’t have any pat answers – the birth of a child is as much a hopeful thing as it is a scary thing. There’s a lot of fear in this book, just like the world we’re living in now. But The Hard Tomorrows reminds us that life is worth living and the future is worth fighting for because of the people we love and care about. There is beauty in choosing to fight. There is beauty in choosing to hope.

READ MORE

Leave a Reply