Fantagraphics has a long history of publishing important anthologies that provided a snapshot of the alternative and underground comics of that era. Kim Thompson was an important personage in this endeavor, as he was the key figure behind Critters, an anthropomorphic animal anthology published from 1985-to 1990. Freddy Milton and Stan Sakai were key figures in that series, pushed by Thompson because of his love of cartoonists like Carl Barks and similar works that he grew up on living in Europe.

Thompson later edited Zero Zero, published from 1995-to 2000. The directive for this anthology was that autobio comics were banned, as they seemed to make up much of alternative comics at the time. It had a lot of continuing serials, including “The Search For Smilin’ Ed” and “Shadowlands” from Kim Deitch. Richard Sala serialized his classic “The Chuckling Whatzit,” and Derf published a shorter version of “My Friend Dahmer” in the anthology.

Joining Fantagraphics as a co-publisher, Eric Reynolds launched MOME in 2005, and it kept going until 2011 with 22 issues. It was initially conceived as a spotlight for a core group of young cartoonists that included Gabrielle Bell, Paul Hornschemeier, Jeffrey Brown, Anders Nilsen, John Pham, and others. He quickly added Eleanor Davis and Tim Hensley to the mix, along with experienced cartoonists like David B and Lewis Trondheim. For the most part, the series was of extremely high quality, and Reynolds really hit a stride as an editor in terms of balancing material and sequencing it in interesting ways.

In 2017, Reynolds launched NOW after approximately another five-year gap. Editing anthologies is a time-consuming and exhausting task, but Reynolds learned some lessons. He’s published eleven issues to date, with each being around 130 pages. After being hamstrung by artists running serials in MOME, Reynolds decided to exclusively run one-and-done short stories in NOW. As part of a recurring feature, I’m going to review one issue a week for the next three months. I tended to review MOME in bunches since there were so many serials, but it makes more sense to approach each issue of NOW as its own unique entity.

NOW #1 has plenty of well-known talents, many of whom are on the Fantagraphics roster. In fact, a number of its contributors had entries in MOME. However, in the late 10s and early 20s landscape for comics, it behooved Reynolds to take advantage of the rapidly diversifying pool of cartoonists from which to draw. MOME, especially in its early days, was criticized for skewing too much toward memoir and had too little diversity, with too many men being a primary critique. In the first issue of NOW, the gender balance was about even.

Reynolds had said that he wanted MOME and NOW to be for people interested in alternative comics who had perhaps read a graphic novel or two, and wanted to see what else was out there. MOME improved when he started to trust his instincts and started to publish weirder and more difficult work, as opposed to some vague idea of “accessible.” In NOW #1, he continued to follow those instincts, making it a rich and varied read.

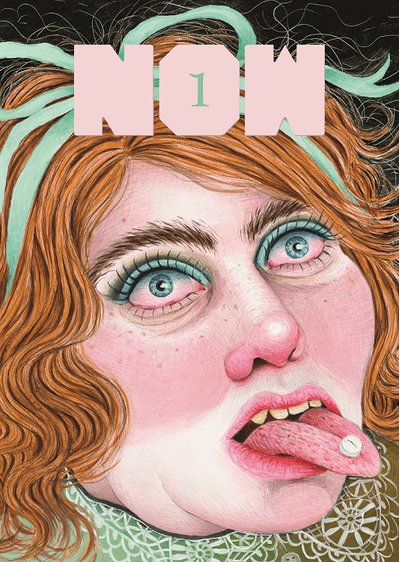

One difference between NOW and MOME is the former’s use of a new cover, as opposed to a piece of art from the interior. For the first issue, it was a slightly grotesque portrait by Rebecca Morgan, titled “Plan B on Easter Sunday.” Five years after this issue was published, the topic of a woman’s right to choose remains sadly timely, though this image is a sly satire of taking communion during Catholic mass. Considering Catholic attitudes toward both abortion and birth control, the image is even funnier, as the woman in the image is wearing her Easter best.

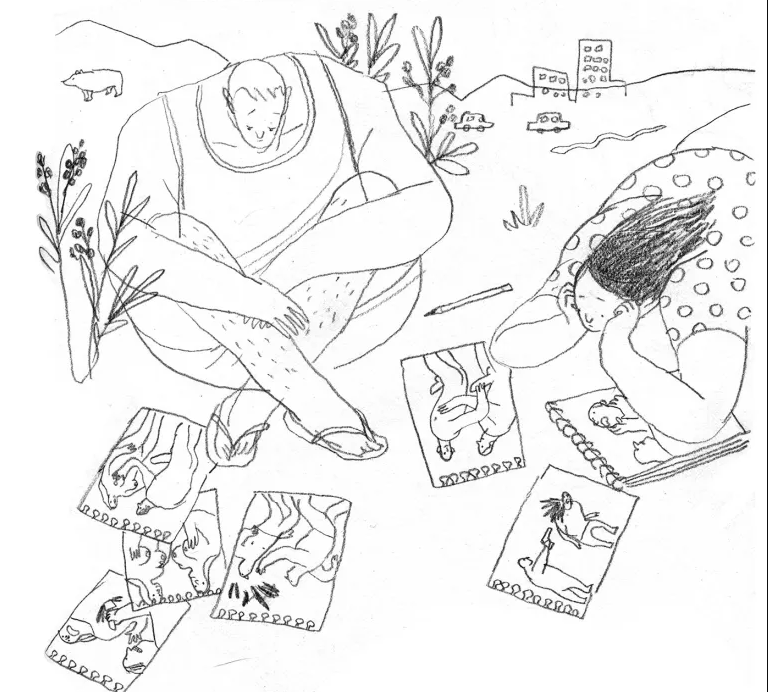

There are three anchor pieces that take up around fifty of the anthology’s 128 pages, and they are all wildly different. Eleanor Davis seems incapable of doing the same thing twice while working the bulbous, bulky characters she’s been drawing of late. In “Hurt or Fuck?”, Davis explores intimacy in a bizarre post-apocalyptic world of some kind. In the story, the last remaining man and woman are hanging out when the woman wants to touch him. He’s alarmed because he’s worried that she might accidentally hurt or fuck him, and that would complicate their relationship. That begins a long entanglement as she draws people touching, and–at his request–people fucking and hurting each other. There’s a beautiful ache to this story of an unconventional romance that is heightened by its bizarre genre elements. Davis’ mastery of gesture is so raw that looking at some of the drawings hurts.

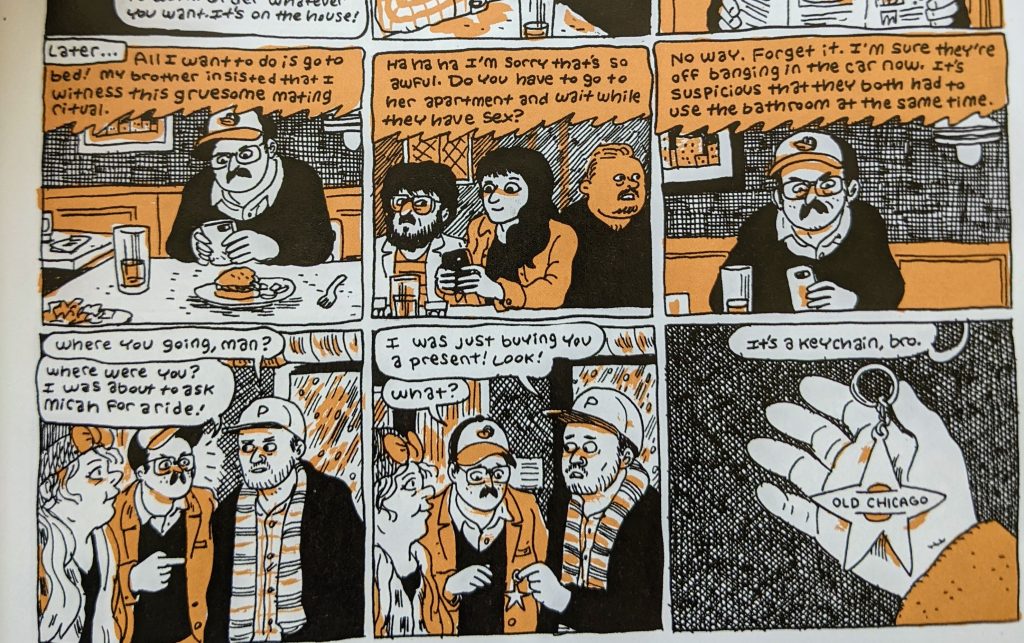

Noah Van Sciver’s autobio story about visiting Denver as part of an art exhibition is hilarious, because of the way he depicts his younger brother Jonah. Van Sciver depicting himself as constantly frustrated, put upon, and wanting nothing more than some recognition makes him an ideal straight man to Jonah’s crude horndog ways. Jonah is undoubtedly depicted as a ridiculous, thoughtless asshole, but he’s a harmless one who makes a great foil for his serious artiste brother. Van Sciver’s comic timing just gets sharper and sharper, resembling a 20s comic strip like Bringing Up Father as much as it does a modern memoir strip. The orange wash mixes well with his usual dense cross-hatching, creating a slightly oppressive atmosphere.

The third anchor piece is from the brilliant French cartoonist J.C. Menu, one of the founders of L’Association and the founder of L’Apocalypse. Menu’s “S.O.S. Suitcases” is a dream comic filled with exaggerated expressions and surreal logic. Drawing himself trying to retrieve his suitcase from a train that’s part of a sinister conspiracy fits like a glove in this anthology without overwhelming the rest of the content. It’s quirky and has funny drawings, but it’s not so distinctive that it stands out in an anthology full of quirky entries. Menu has very few comics that have been translated into English, so that alone makes this entry a treat.

As an editor, Reynolds seemed set to feature as many different kinds of visual approaches as possible. The end of the anthology is anchored by Antoine Cosse’s “Statue,” a science-fiction story about a piece of sentient technology designed to find pods with humans in them, wake them up, and then either reconstruct them or liquify them. Cosse’ uses an expansive open-page layout, starts the story with a single brown shade, and then switches to a day-glo color scheme as the robot imagines their experiences. It’s a grim story that implies that the technology they created saved the human race, but at a terrible cost. Cosse’s extensive use of negative space and a spare line couldn’t be more different from Malachi Ward and Matt Sheean’s science-fiction story, “Widening Horizon”, which is an alternate history of space travel where it had begun much earlier, involved China, and also featured a partnership between the US and USSR. Ward’s approach wouldn’t have been out of place in a mainstream genre comic: naturalistic drawings, bold use of color, and fairly standard use of grids. Placing it before Cosse’s story was a clever choice in how both address futurism in radically different ways.

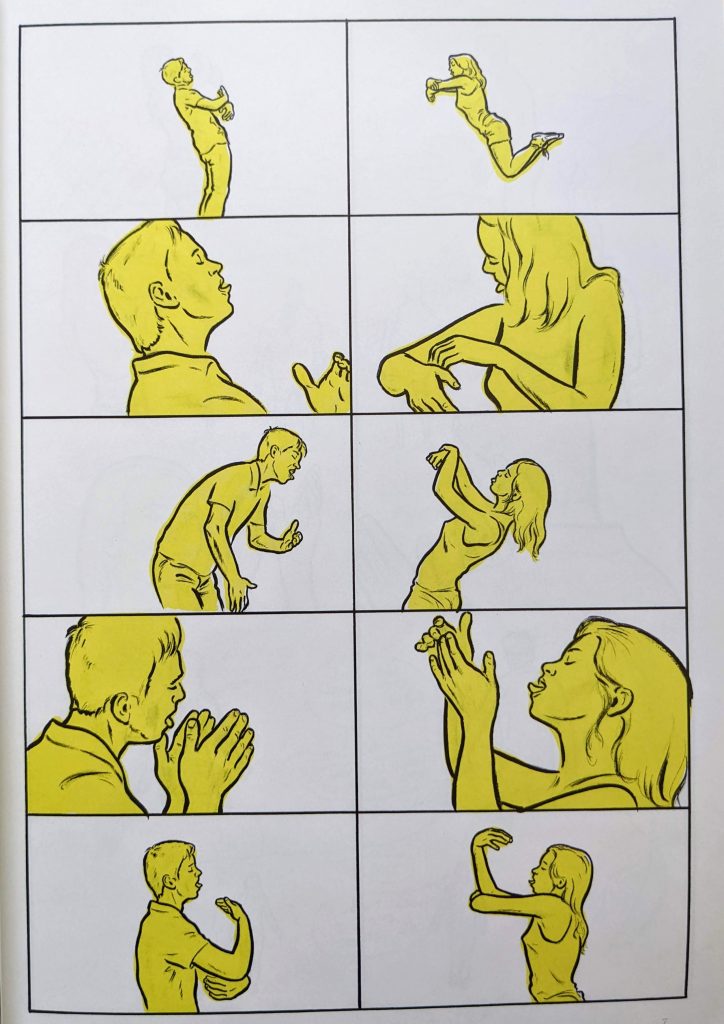

In many respects, the first forty pages of the anthology seem to have been sequenced by Reynolds in a deliberate manner. They are a sort of celebration and investigation of movement and gesture: the foundations of cartooning. Sara Corbett’s full-color, densely-hatched one-pager about an old woman following her cat into a park is titled “Constitutional.” It’s a pleasant, restorative walk, shaking off the rust, just as this story is for both this issue and the anthology in general. Experimental cartoonist Tobias Schalken (of Eiland anthology fame) follows with “21 Positions,” featuring a formally-dressed couple engaging and intertwined in complex dance moves, some of which double as sex positions. Schalken followed that with “The Final Frontier,” which inverts the first strip by having a couple engage in explicitly sexual acts–only they are doing them in parallel without actually touching. It highlights the objective hilarity of making out while completely honoring the ardor and affection of the couple. It’s fitting that the strip after this is Davis’ “Hurt or Fuck?”, which also addresses issues related to intimacy.

Dash Shaw, another MOME veteran, follows Davis with “Scorpio,” a story about one of the potential consequences of sex: pregnancy. Shaw takes things in a different direction, as this was about the disastrous 2016 US presidential election and a couple expecting a child. Her descent into pre-eclampsia and induced labor is paralleled by the shock induced by the election results, with a grimly funny punchline. Joy and ambivalence are inextricably linked. MOME original Gabrielle Bell pops in for a funny one-page palate cleanser about watching a nude neighbor and finding excuses to see if he was still watching TV naked. The final panel, where she’s red-faced and embarrassed over her wanting to see his large penis, is a great punchline.

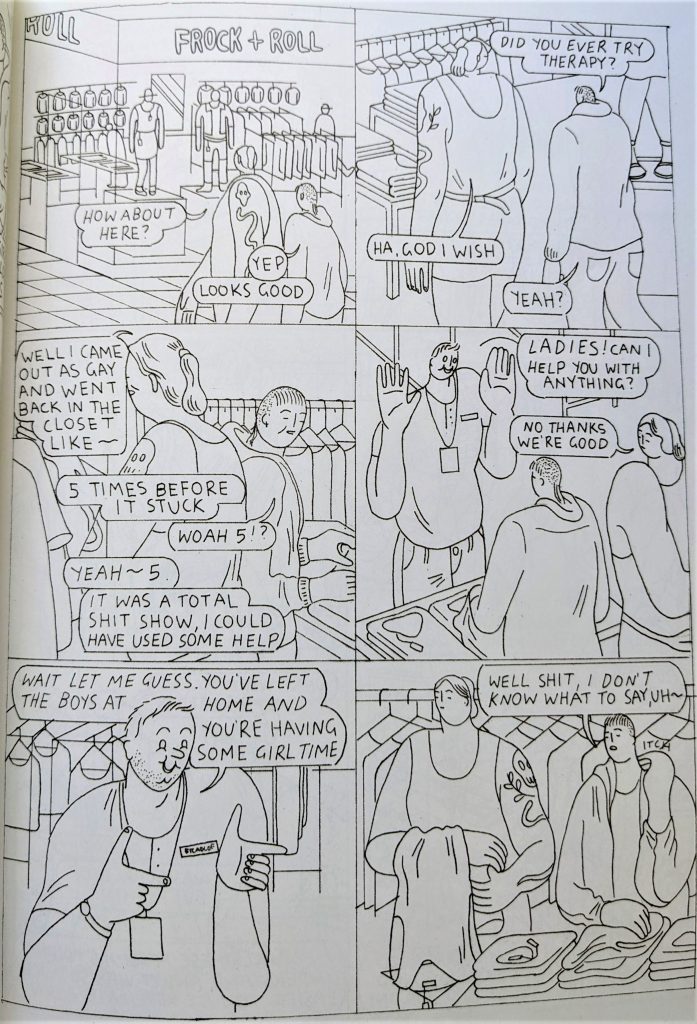

Tommi Parrish has a strip after Van Sciver’s comedy of awkwardness about two young queer people in a mall. There are three interesting elements in this comic. The first is Parrish’s big, blocky figures that take up a lot of space. The intense amount of negative space in their strip only further emphasizes their scale. Like Davis, this is a deliberate choice, as it’s a way to exaggerate their physiognomy and mass while still retaining a tether to naturalism. Secondly, the conversation they have, about sex, queer identity, and having to go through painful periods of going with what society wants is deliberately subversive and questioning. Third, this conversation takes place in a mall. They even go along with an obnoxious male sales clerk asserting that they “left the boys at home.” The way they take up space and the conversation they have in a nexus point of conformist capitalism is all connected and depicted by Parrish as both a radical act of resistance because of the context and a warm, intimate conversation.

After Parrish’s piece roughly halfway through the first issue, the anthology switches focus to speculative fiction, beginning with Kaela Graham’s story about girls scaring themselves with stories about wolves and how one of the girls winds up joining them. Told in blacks and deep purples, it’s more about atmosphere than actual story. Daria Tessler’s intricate “Songs In The Key Of Grief,” a murder mystery about a mysterious DJ who is actually an intelligent colony of mushrooms follows. The elaborate decorative aspects of this piece set it apart from anything else in this issue. Conxita Herrero’s “Here I Am” is metafiction. On the surface, it’s just an ordinary story about a woman talking to a man in her new apartment that came furnished–including a remarkable red chair. However, Herrero notes that the story was based on Gabrielle Bell’s “Cecil and Jordan In New York,” which was about a woman ignored by her boyfriend until she grew so despondent that she turned herself into a red chair. This was a clever way of creating tension solely through context, much like a Marcel Duchamp piece.

Sammy Harkham’s one-page piece about Marlon Brando in Tahiti, having cast off his old life, is a fitting end for the issue. With NOW, Reynolds has published pieces mulling over the human experience in the present: sex, birth, death, dreams, desires, and more. He has also published pieces wondering about the future and different kinds of being. These are questions of ontology, and Harkham’s piece quotes Brando saying that his actions are no more significant than the grains of sand he is sitting on. While that may be true, it doesn’t stop us from struggling with our conceptions (and self-conceptions) of being. It only makes us want to engage them more fervently, and there’s no better way to do that than through art. As such, NOW #1 acts as an ideal mission statement for an editor who wants to engage a new audience with the most interesting cross-section of today’s cartoonists.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply