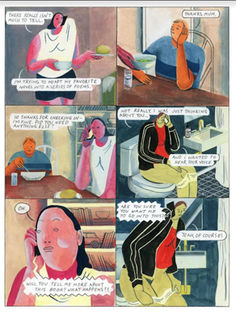

The realistic storyline and surrealistic art of Tommi Parrish’s Men I Trust initially seem at odds with one another. The painted panels of Parrish’s work contain people with oversized bodies and tiny heads, the colors of characters and backgrounds changing from one image to the next, and even a few seemingly random sketches of Garfield from time to time. That approach contrasts with the realistic story of Sasha and Eliza, as they try to negotiate challenges steeped in reality. Eliza is a single mother who works at a deli and wants to be a poet, in addition to being a recovering alcoholic. Not surprisingly, she struggles with paying her bills, juggling her schedule, and trying to raise her son. Sasha has moved back home to live with her parents, doesn’t seem to have a job, and has struggled with suicidal ideation in the past.

However, the art often works in service of this story. Many of the characters act more on emotion and desire than they do on intellect, more with their bodies than with their minds. They also seem changeable from one panel to another, moving from everyday conversation to anger to apology, all within one page. Their lives often feel random and surreal, even if the events are realistic and, even, mundane. When a bill collector calls Eliza when she’s trying to get Justin into the house, it feels absurd. Similarly, there’s a television show called Chat Time where a TV personality who renovates homes on his show is praised for buying an old hotel that was providing living space for the unhoused, so he could develop it into “a high class place for high class people.” He then asks, “And I’m the villain? How dare you.” The host ends by talking about how the renovation show will make for “some sensational viewing.” It’s easy to feel the world is surreal after such an exchange.

The bulk of Parrish’s work follows Sasha and Eliza’s trying to become friends. More accurately, Sasha works to try to become Eliza’s friend (and possibly more), while Eliza tries to manage her commitments. Eliza initially tries to brush off Sasha’s invitations, but Sasha is diligent. She shows up at Eliza’s work with lunch after Eliza had said she couldn’t meet up for a meal. She attends Eliza’s poetry readings and compliments her profusely. She even offers Eliza a way to make extra money by having dinner with the aforementioned local TV personality, an escort, essentially. Not surprisingly, that evening doesn’t go well.

When Sasha isn’t with Eliza, she’s often talking to her mother who either doesn’t understand Sasha’s struggles or she’s choosing not to engage with them due to a possible suicide attempt earlier in Sasha’s life. Sasha doesn’t feel her parents truly see her, but she has no other option than to live with them. Part of her attraction to Eliza, whom she barely knows when she tries to kiss her, may simply be that she’s looking for a connection to anybody else. Eliza, too, is looking for any sort of connection, as she’s become completely isolated. Her days consist of going to work, going to a twelve-step meeting, and picking up her son. In fact, when she and Sasha are walking to the subway, she admits she doesn’t know how to have a conversation anymore: “It’s normal for people to talk to each other about their lives, right?” She then proceeds to lay out how much she feels she’s suffering under the weight of her responsibilities.

Parrish’s work shows how difficult it is, especially as a woman, to try to balance everything in their life. Once one setback occurs, it can easily lead to another and another. Though Eliza doesn’t talk about her alcoholism and any direct effect it had on her current life, whether relating to employment or the end of her marriage, she does reveal that her mother was an alcoholic and, thus, Eliza is trying to be a different parent to Justin. Whenever that doesn’t go well, then, she feels like she’s failing her son. Given her experiences with her mother, that pressure simply adds weight to an already complicated situation.

In fact, one of the sub-themes of the book is about parent-child relationships and boundaries. Sasha’s mother talks about how afraid she was when Sasha was living far away from them and was struggling with her depression, yet Sasha doesn’t feel that her parents truly care for or understand her. They try to talk with one another but never make much progress. Eliza is always thinking about her son, even when she’s late to pick him up, but she feels her failures far outweigh and outnumber her successes with him.

Despite the title of the work, there are few men around, and those who do appear aren’t very trustworthy. However, the interactions between the women in the book are also not well-grounded in trust. Eliza doesn’t trust Sasha’s motivations, while Sasha doesn’t trust her mother (and vice versa). Neither Eliza nor Sasha seems to trust themselves. Both of them have struggled to get to where they even are in life, yet they mainly see where they’ve fallen short. There is a moment of hope at the end, though, at least for one of them. Perhaps at that point, they’ll begin to trust that life has more to offer than what they’ve seen so far.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply