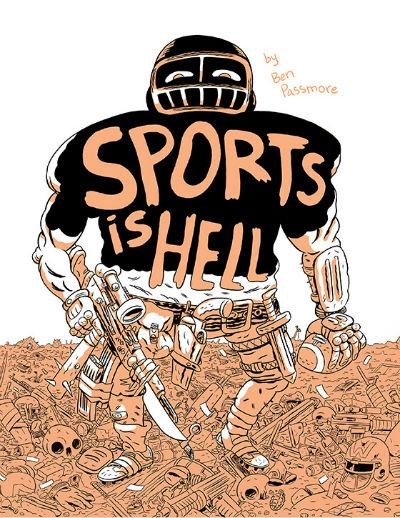

As Koyama Press winds down its publishing operations, they’re certainly, to use a sports cliché, “leaving it all on the field.” Strong “ninth inning” works from Emily Carroll, Michael DeForge, Patrick Kyle, Keiler Roberts, and others rank among the best things ever put out under Annie’s imprimatur, and, to that distinguished list, we can now add Ben Passmore’s latest, Sports Is Hell. Sports Is Hell is a distorted funhouse-mirror look at contemporary American socio-political and cultural divisions that uses the hyper-violent capitalist spectacle that is the Super Bowl as both a metaphorical and literal case study of, essentially, every damn thing that’s wrong with our body politic today.

Certainly, as far as garish examples of excess go, they don’t come much more appropriate or obvious than the NFL’s annual championship game, and, while it may not be a 2000AD-style gladiatorial death match yet, portraying it as such right on the cover doesn’t feel especially far-fetched. The surprising thing readers will find once they open the book up and read it, though, is that the majority of the action takes place off the field, with the game itself serving as the crux of an ideological smorgasbord of competing philosophies, some of which are limned out within the context of the contest, while others are defined by the depth and fervor of their opposition to both it and all it stands for.

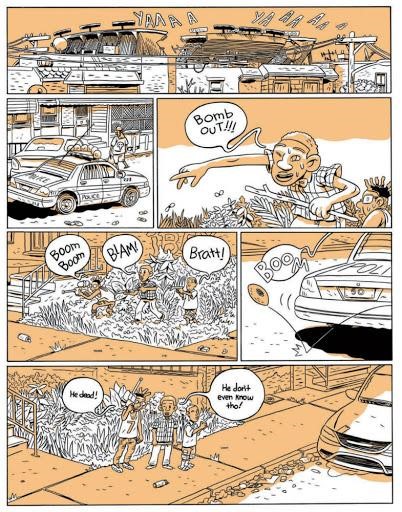

Among the book’s rotating ensemble of sub-protagonists, star wideout Marshall Quandary Collins is the most obvious analog for a “real life” sports figure in that his decision to kneel during the national anthem as a silent protest against police brutality is pretty clearly “ripped from the headlines” generated by former San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick. Yet there’s a crucial bit of depth that Passmore adds to this scenario that the news media has largely ignored, namely: Collins’ status as a multimillionaire athlete necessarily removes him from the realities of the very problem that he’s attempting to draw attention to. There was some discussion of this at the margins when Kaepernick inked a lucrative endorsement deal with Nike largely on the back of his iconic status as a cultural “touchstone” figure (it’s rather unusual, to say the least, for a guy who isn’t even playing for any team to be selected as the face of the world’s largest shoe company), but by and large, the economic divide between where the former Super Bowl QB is and where those who are beaten by the cops are has remained unremarked-upon — not so here.

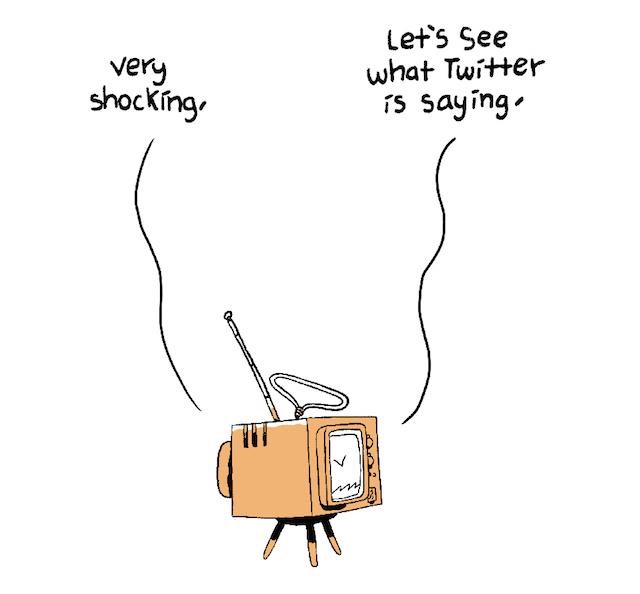

And yet, this is hardly some polemic designed to make Kaepernick or the other kneeling players in the league look like hypocrites, and that non-didactic approach carries through to all corners of the book. The two play-by-play announcers covering the game — one a partisan of Collins’ team The Birds, a stand-in for the Philadelphia Eagles, the other favoring The Whites, the fictional equivalent of the dynastic New England Patriots — offer fairly standard-issue takes on the whole kneeling situation. Their commentary, though, is just a springboard to the larger one Passmore offers by way of the various and sundry Birds fans we meet, among them a pair of Africa-American anarchists, an old-school black revolutionary, and a faux-radical white couple who are about to lend their dubious “support” to a Black Lives Matter rally. Each have their pros and cons, and Passmore utilizes these broadly-drawn caricatures (calling some of them fully-fledged characters is probably being too generous by half, but it’s also not necessarily a detriment) to explore everything from the patriarchal and misogynistic internal cultures of some black revolutionary movements to the lack of a cogent philosophical through-line in certain segments of the anarchist community — the latter being particularly surprising given the cartoonist’s own well-established politics. It’s admirably honest for Passmore to point out some of the deficiencies in his own belief system and those who agree with and espouse it — and in that very specific regard some limited comparisons to Alan Moore and David Lloyd’s V For Vendetta are not at all out of place. But who are we kidding? If there’s one thing anyone who’s read Your Black Friend knows, it’s that Passmore is at his very best when he goes places other artists are either unqualified, too afraid, or both, to venture.

In terms of the art, in Sports Is Hell Passmore seems to be refining his figure drawing and smoothing out certain rough edges in terms of panel composition. Some of this book’s most effective cartooning, for instance, takes place during a post-game riot/rebellion, where we follow ostensible “hero” Tea through the chaos as she searches for the friend she’s been separated from. Passmore’s expert placement of shadow and smoke effects in the midst of jam-packed groups of people and flying objects shows just how far he’s come when it comes to drawing effective crowd scenes — yet, thankfully, he’s lost none of the punk/DIY ethos that has been the backbone of his work from the beginning. His unique approach to facial expressions, equal parts naturalistic and exaggerated, offers perhaps the best example of this, seeing as how he isn’t afraid to “get cartoony,” but does so in a manner that’s organic and very much rooted in the cultural realities of the characters he’s depicting. The sepia-toned color palette employed throughout took me a few pages to get used to, I admit, but by the time all the various pieces of the story are coming together and Passmore’s narrative and thematic tracks are both reaching their crescendo, I literally couldn’t see the art being colored any other way. If there was ever any doubt that I was witnessing a cartoonist working at the height of their powers, this dispelled it once and for all.

As Passmore eventually settles on Tea as the audience’s primary point of identification, the ease with which he meshes the personal and political — with which he transitions from the “macro” to the “micro” to the betterment of both — is as smooth as a fade-away jump shot at the buzzer. While Collins stands as a distant figure that could either bring peace to the city with the wave of a hand or ride an increasing tide of hysteria to becoming its new strongman-style leader, it is Tea’s struggles with her own belief system that function as the real heart and soul of the proceedings. Her ultimate decision may disappoint and frustrate some readers looking for validation of their own worldview through her, but this ultimately non-polemical approach is the strongest feature in a book that contains nothing but. Passmore has been creating a singular and increasingly accomplished body of work for several years now. With Sports Is Hell, he makes a strong argument for being both one of the best and most necessary cartoonists of our time.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply