Debbie Fong’s 2018 mini-comic Greenhouse was a revelation for me. This intimate work of art juxtaposed the natural growth of plants with the decay of the individual locked in an isolation of their own making. It is a beautiful, tragic, and poignant comic that pointed to the perils of life led out of balance. Fong’s newest work, Wild (self-published through her Pomo Press imprint in 2019), furthers this idea by trying to capture the possibilities of finding peace through balance.

We live in a world constantly churning with endless streams of information, overstimulation, things to do, things to see. Our ability to easily connect to the larger world has put more voices and options on our plate, overflowing it with content and opinions, celebrations and outrages. It’s hard to be alive in Western society without feeling overwhelmed by it all. To deal with this, there’s been a push towards simplifying — to engage in either expensive bespoke consumerism or journey on a spiritual bypass — to pare down in a manner that tricks the self into finding purpose and meaning while still enjoying the comforts of all the modern advances in luxury and comfort.

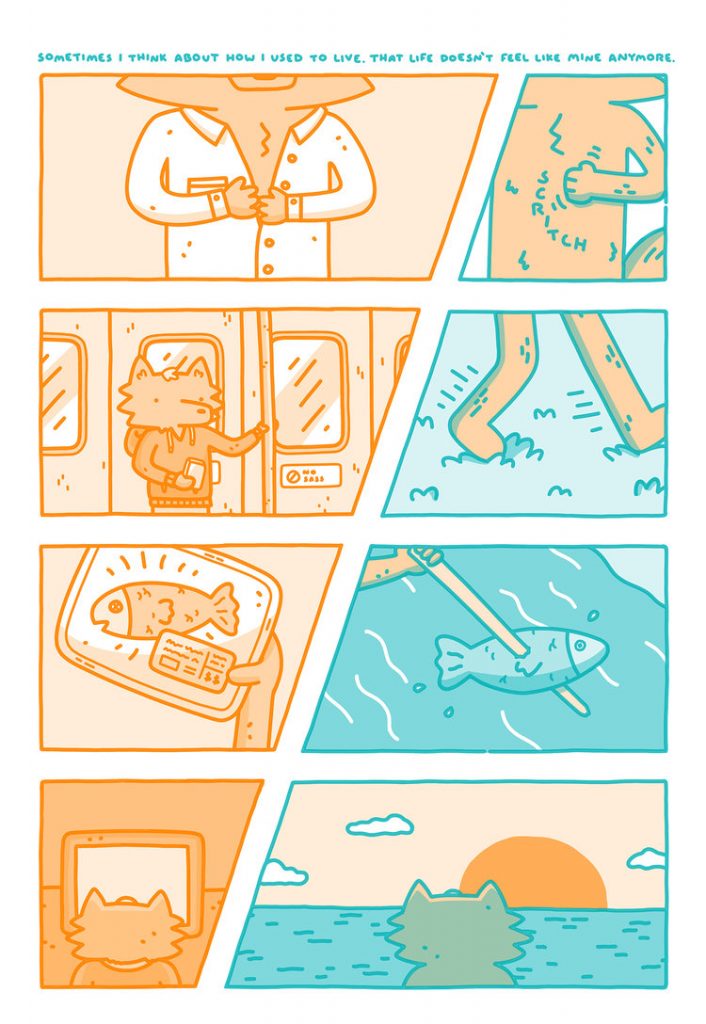

In Wild, Fong posits that there is a peace in an authentic melding of the extremes. Her main character, an anthropomorphized fox named Flint, seeks inner happiness and centralized tranquility. He does so, initially, by joining a burgeoning Naturalist Movement, abandoning his job, his home, and most of his possessions in order to live authentically out in the woods. He keeps his phone, though, so as still to have access to the world around him. It allows him to maintain some of the relationships he had in his own life. Flint also seems to have no qualms about the occasional trip to the Go Go Mart in order to purchase snacks from the vending machine.

All of this is captured in hard lines against soft backgrounds. Fong is especially deft at how she lays out her pages; she positions panels in a way that enhances meaning, drives the pace of the reading, and adds to the beauty of the book. Likewise, her use of colors easily aids the reader in distinguishing between the past and the present, saving the rich blues that permeate the book for the action as it is occurring, washing what has come before in a soft orange hue. Above all else, Fong is clearly in command of her skills as a cartoonist.

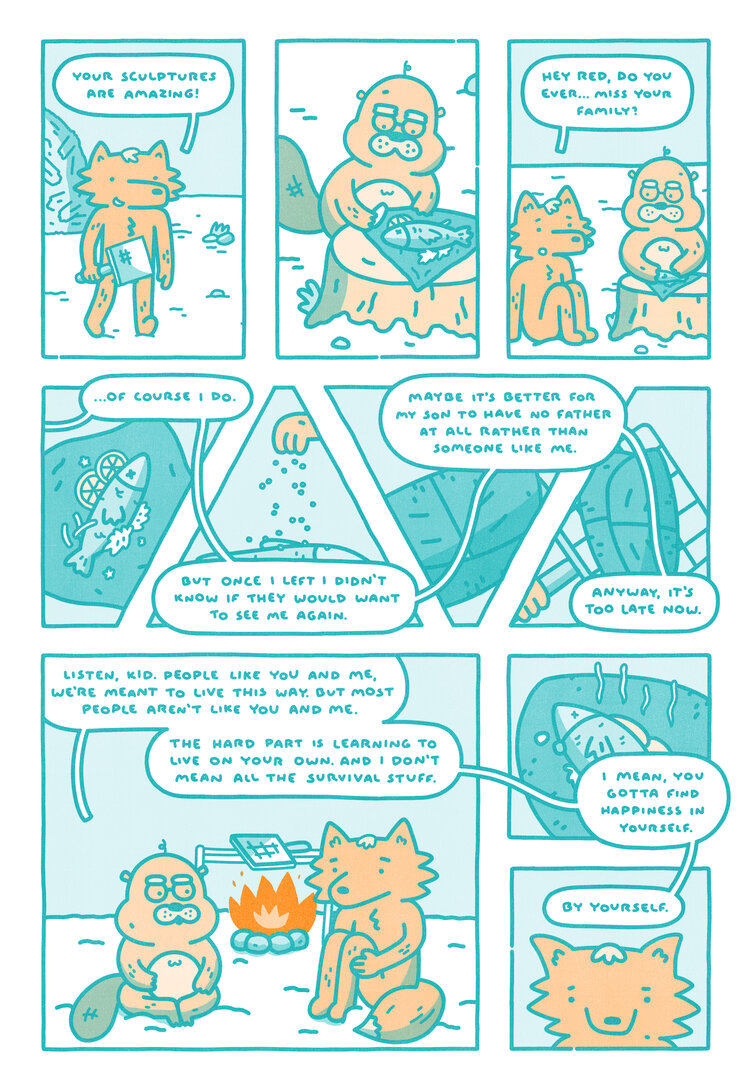

While Flint is still able to journey into the Big City to meet up with his friends for a night of role-playing games, it seems as those his friends are less inclined to meet him out in his new environs and participate in his lifestyle. As such, Flint begins the become more and more isolated and lonely. This is ameliorated when he meets another Naturalist, a beaver named Red, and they form a small community together. Red is a practitioner of tai chi, a form of martial arts whose purpose can be meditative and can be used to help achieve a sense of calm and balance.

In order to be living this life, though, Red had to do more than abandon his job and his home; he also abandoned his family, specifically his young son. Here, Fong inadvertently points to one of the major problems of the Naturalist Movement and so many that feel the need to “simplify their lives” — the impulse is driven by ego. The desire to pare down and do away with that which is “unnecessary” already speaks to privilege — not everyone has the opportunity to abandon their obligations. When someone walks away from their child in order to “find” themselves, it speaks to that individual’s enormous selfishness.

Wild, in its idealism, tries to have its cake and eat it too. It points to this dualism and hypocrisy but just allows it to be — Fong provides no comment whatsoever on its implications. Through this, it borders on being naive and almost too cutesy, as if the pat answer is enough, as if the inference of the issue is all that is necessary. Any harder examination would be almost beside the point. But, at its heart, its message is an important one that is easily eyed cynically by those too world-weary to accept it.

And yet, even with all this working against the premise of Wild, Fong is still able to bring a softness to Flint’s story. While perhaps not really acknowledging these issues, Flint ultimately lands on the realization that, as with everything, life requires balance. Happiness, perhaps, rests in the intersection of the life we have to lead and the life we want to lead.

The muted risographed blues and oranges of Wild’s 24 pages may not be a sturdy enough vehicle to carry the philosophical heft of Fong’s thesis, but perhaps Flint’s story provides a spark for a larger conversation, something more nuanced and real. There is absolute value in having a starting place from which to start an idea. Debbie Fong’s Wild is just that, and, though it might be a bit naive in its presentation, it gets to a possible solution through gentleness and a kind heart.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply