Australia’s Chris Gooch pokes around in some uncomfortable, ugly places as he explores psychological and visceral horror through a variety of genres. There is a profound level of cynicism about human relationships present in his work that reaches its nadir in his first long-form graphic novel, Bottled (2017), that’s a logical extension of his older work: the nasty, punchy short stories collected in Deep Breaths (2019). However, working in a post-apocalyptic environment in his most recent book, Under-Earth (2020), Gooch offers hope for human connection in the most hopeless, degrading setting possible; a sharp contrast to the often horrible events in his other works that were set in perfectly comfortable environments by people who were nonetheless unwilling to see the humanity in others. Exploring the deterioration of empathy and how other people become objects-at-hand instead of beings that possess the same hopes and fears that we have seems to be the heart of his work. However, it’s only in Gooch’s most recent work that he has explored how empathy can be nurtured in the most unlikely of settings.

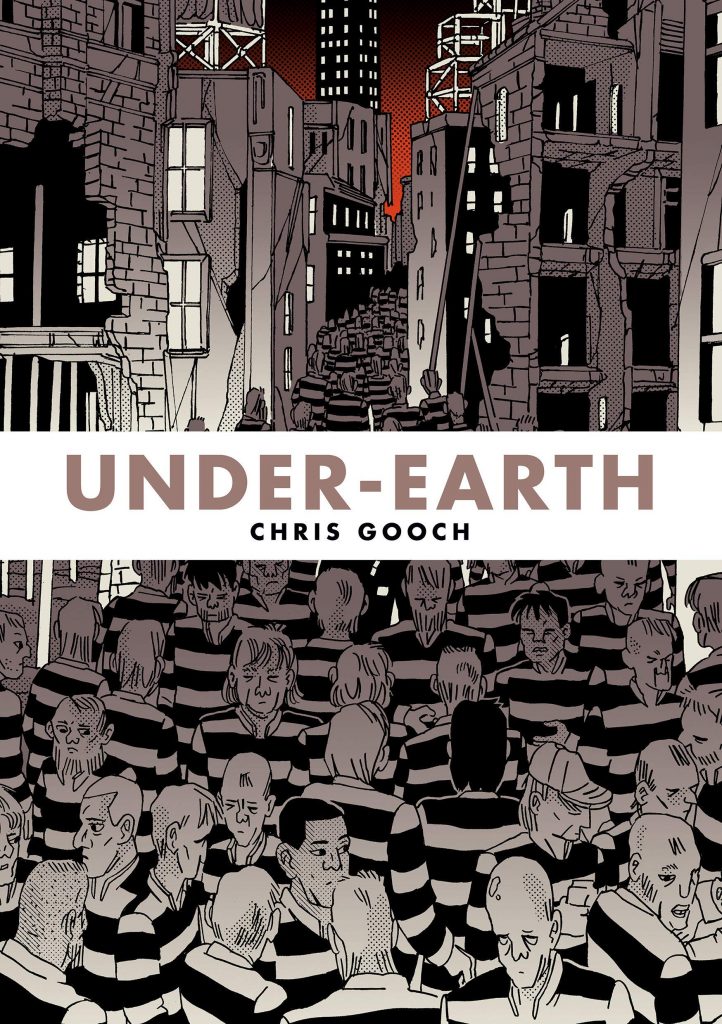

Published by Top Shelf, the design of these books is top-notch. Most of these comics were originally published as minis or in anthologies, and care was taken to maintain the spot colors and other visual hallmarks of Risograph printing. Gooch’s character design borders on the grotesque, with exaggerated features and an almost aggressive disinterest in idealizing his characters’ looks. In this vein, his comics seem derived from the Will Eisner-Frank Miller-Paul Grist succession of creators, all of whom heightened reality with their grotesque, cartoony characters and moody, film noir-inspired settings with a number of cinematic tricks moving pages along quickly. The difference is that Gooch melds that approach with DIY comics visual techniques like spot colors and a determination to bring out the grotesque in everyday situations.

In Deep Breaths, the bulk of the stories are about betrayal and how different people react to it. Sometimes, it’s a blunt force object. In “Buddy,” it’s a horror story about how a boy named Will doesn’t want to be paired up with another boy named Alexander at school recess. Of course, Will is actually a monster who devours him in the forest that he leads him into, but it’s suggested that Will is going to get his own just desserts at the hands of another recess “buddy” in the end, perpetuating the systemic flaw at the heart of this system. The betrayal here is not a betrayal by a friend, it’s a betrayal by the teacher and everything they promised with regard to keeping kids safe. What’s worse, it’s a system the kids can’t opt-out of.

“Wednesdays,” a moody slice-of-life story in Deep Breaths, is about three married friends on their weekly jaunt to drink beer and swim. They have access to this after-hours indoor pool because the son of one of the friends works there. This story features a conceptual betrayal, as one of the men reveals he talks about their beer-drinking adventures with his wife afterward, whereas the other two note that they keep it a secret. The final reveal of a potentially disastrous mistake by one of them is every bit as ominous and frightening as the monster in “Buddy,” because one of the friends notes that if they were discovered, both he and his son could lose their jobs. The bobbing beer can they accidentally leave behind is made threatening by the eerie use of blue as a spot color, spotlighting betrayal through indifferent carelessness.

“One To Make Him Grow” is the least subtle story in Deep Breaths. A boy is dragged to another kid’s birthday party by his divorced dad so the dad can hit on the mom of the birthday boy, but the clearly emotionally disturbed birthday boy sees them and commits a shocking act of violence. The story goes over the top in a way that doesn’t feel earned. It’s the most nihilistic story in the collection, hinging on a young kid snapping and performing a grotesque act of violence that seems like an extreme leap in the context of the story’s events. Here, the betrayal is a parental one, but the birthday boy can’t strike out his mom or that dad and so harms the son of the man he saw with his mother.

There are other kinds of betrayal explored in Deep Breaths. “The Effervescent Pill” is about an artist finding himself betraying his own sense of integrity in order to stave off eviction from his flat. It’s a brutal if blunt bit of satire of the worlds of art and publishing, focused on how moving product is always the most important consideration. “Mother” features a woman who finds a used condom while cleaning her home, leading her to realize that either her husband is cheating on her or her daughter is lying about not being sexually active. When both of them offer denials, she simply chooses to pretend the incident never happened, putting the condom away in a box and diminishing its importance to her therapist. She knows that someone has betrayed her, but honesty and authenticity are far less important to her than maintaining a happy status quo. The ambiguity of the story gives it a queasy quality that’s far more disturbing than the straight-up horror in the rest of the collection.

Still, there are bright moments in Deep Breaths: the innocence of two women connecting in “Karaoke,” the businesslike but ultimately compassionate nature of the bounty hunter in “Curse You, Skullface!”, and the awkwardly touching scenes of older men coping with mental health issues together in “Mooreland Mates.”

The collection closes on a quietly savage note in “Braces,” in which an orthodontist who realizes that her son’s bully is her patient methodically tortures him as she installs his orthodontia, making sure he never bothers her son again. It’s a nasty revenge piece that is unsettling because of the power dynamic between adult and child, not to mention doctor and patient. The story circles back to “Buddy,” because even a bully has a certain expectation of how adults are supposed to behave in certain circumstances, and the doctor coldly explaining to him how things are going to be from now on evinces not just fear, but a sense of shocked betrayal at how the rules he understands are being broken.

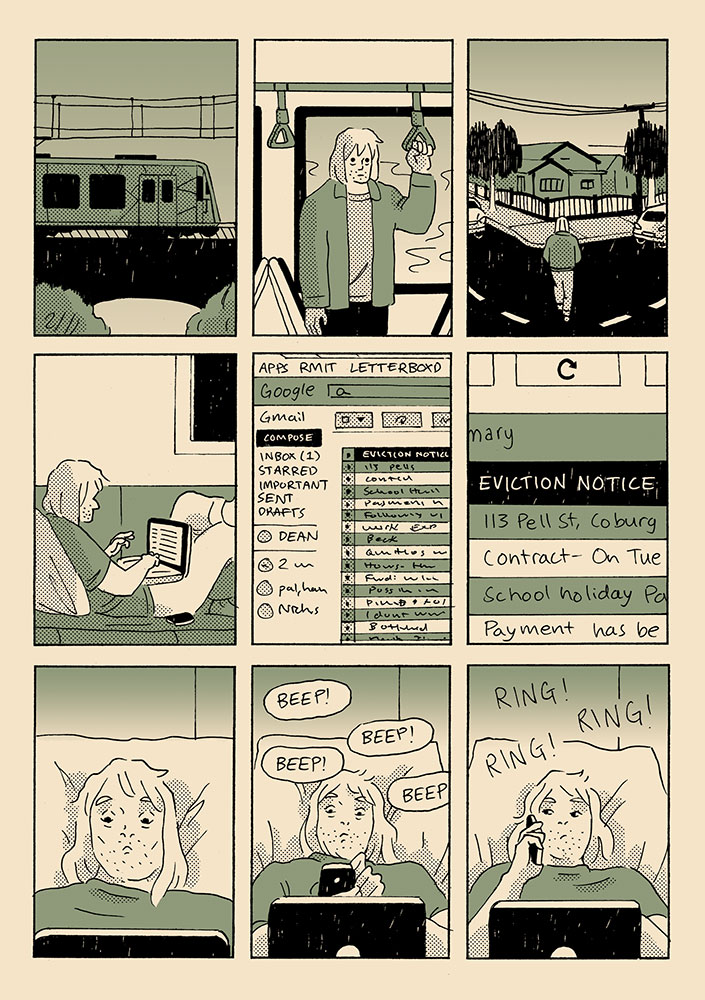

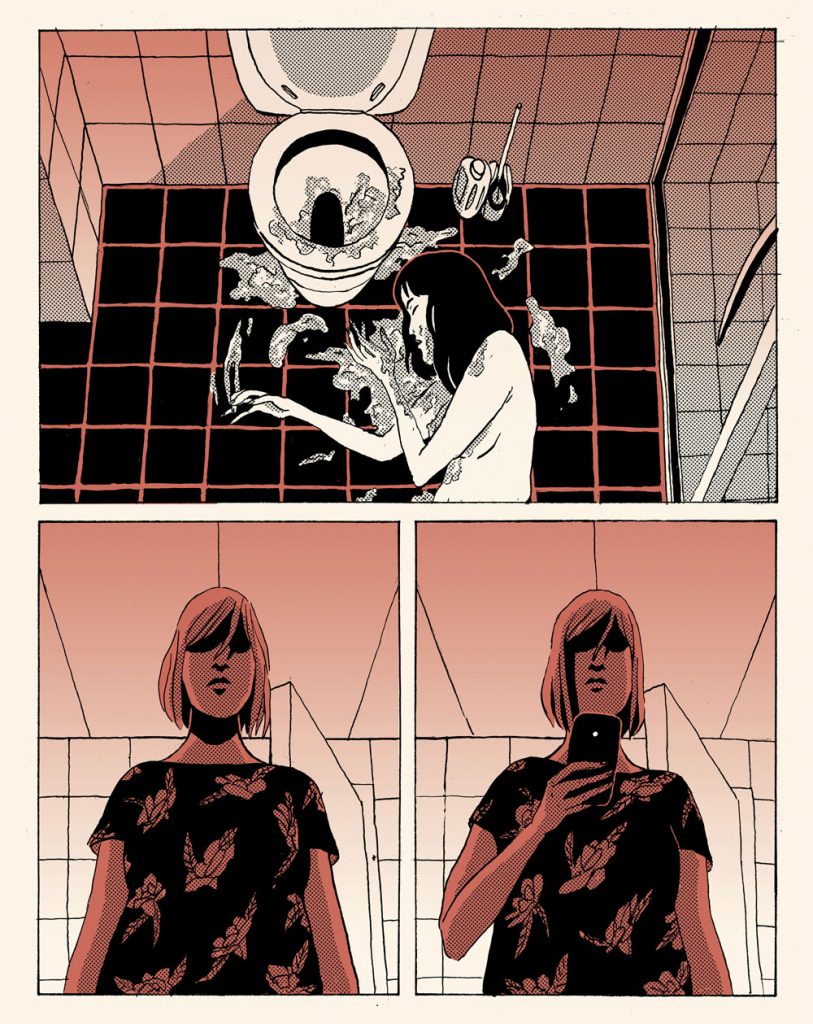

Gooch elaborates on this theme of betrayal and relates it to an almost sociopathic sense of narcissism in Bottled. It’s the story of Jane, Natalie, and Ben, three young people who went to university together. Natalie leaves Australia and becomes a model in Japan, becoming rich and famous. Jane is stuck at home living with her parents, who are constantly screaming at each other. It’s clear her father is cheating on her mom. She wants to rent an overpriced room in a dilapidated house, seeing it as a means of freedom and even a touch of a bohemian lifestyle, but she can’t afford it. When Natalie comes to town, she’s oblivious to her friend’s unhappiness as she yammers on about her exciting life. It’s clear that not only do they not have anything to say to each other when they meet again, they probably never did in the first place.

The book turns when Natalie gets drunk, passes out, and vomits all over herself. When Jane decides to snap a picture, the book tightens into a vicious, petty low-stakes thriller that is no less tense despite those stakes. Jane is a terrifying character, weaponizing her self-loathing and turning it against Natalie to blackmail her and against Ben to manipulate him so she can achieve her pathetic goal of getting a little money to get that place. Having her own trust in others betrayed, it doesn’t take Jane long to seek ruthless revenge that’s less about justice and more about her inability to see others as flawed, real people. Instead of trying to connect with others in a meaningful way, Jane isolates herself from everyone except her mother, and, in the end, she stabs her in the back as well as she spins another self-justifying lie. What makes Bottled so effective is how Gooch initially gives Jane the moral high ground when she learns that Natalie and Ben briefly hooked up. She is the aggrieved party, but instead of cutting out the people who had hurt her or trying to reconcile with them, she chose to attempt to destroy both of them, as though she had been waiting for them to betray her in any way to give her an excuse to do so. All she gets for her efforts is cutting out every important person in her life, without understanding how much more psychotic her betrayal was than theirs. All of this is heightened by Gooch’s quick cuts, fractured narrative storytelling, moody colors, and dramatic poses.

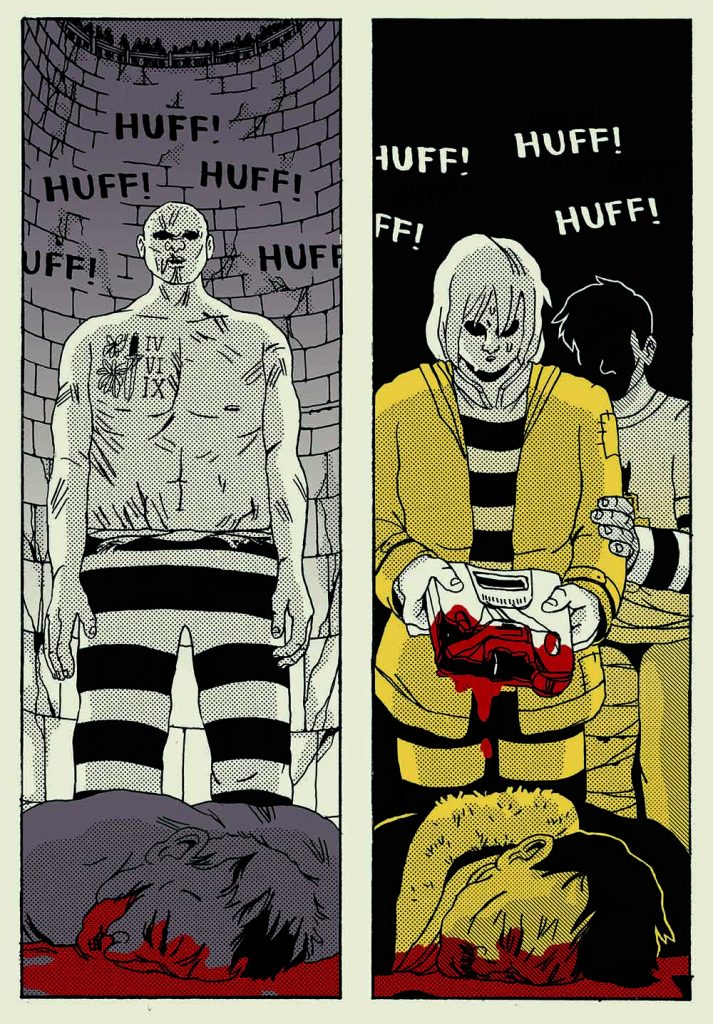

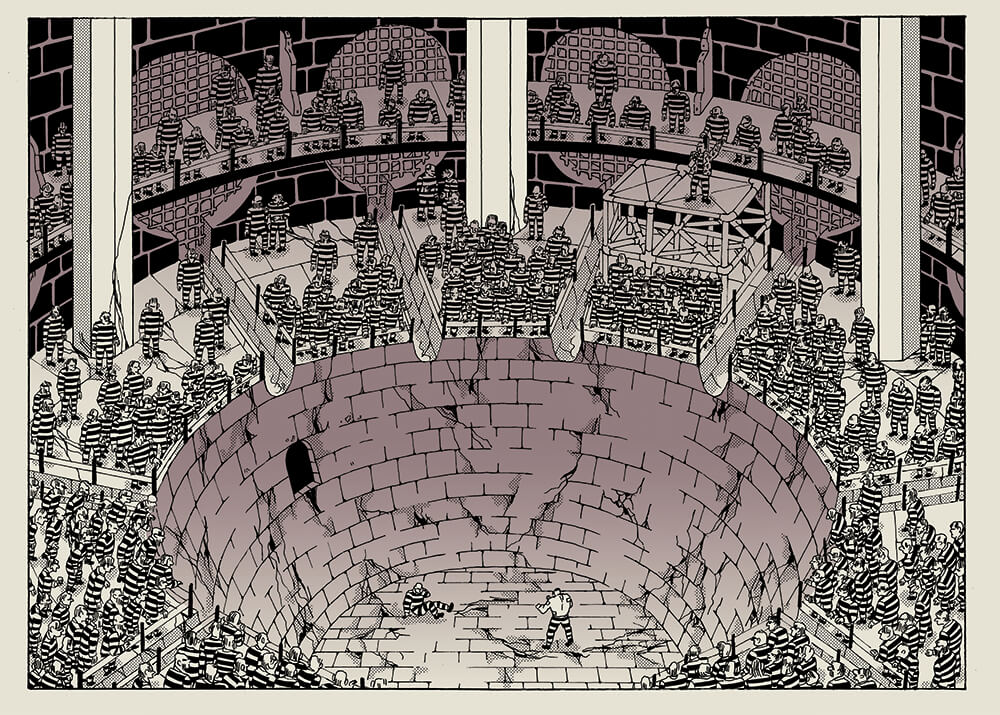

Revenge and betrayal are also on the menu in Under-Earth, Gooch’s massive post-apocalyptic prison saga. Unlike his other work, where nihilism is bubbling under the surface of everyday life, the prison society depicted in the underground complex of Under-Earth has its nihilism out in the open. Life is cheap, labor is a scam, and the stormtrooper guards help keep order by setting prisoners against each other. In a world where escape is impossible and there’s no such thing as justice, there are two parallel narratives involving characters who are desperate to find solace in human connection.

Malcolm, a bruiser trying to put his violent past behind him, not only craves books for stimulation but also befriends Reece, a new arrival who is far too soft to survive in this environment. Zoe and Ele are lovers and expert thieves who do jobs for a prisoner known as the Map King, who runs a nightclub and fight club. He promises them a way out of the city if they can execute a particularly tough job. Needless to say, things aren’t easy for any of these characters.

The story of Malcolm and Reece is notable because of how Malcolm understands all of the systemic barriers that make true friendship nearly impossible in prison. Betrayal is just another currency in this Thomas Hobbes-esque nightmare of the “state of nature,” where survival is based on your own brute strength or your ability to manipulate others. Having been steeped in that way of thinking all of his life, Malcolm’s dogged determination to move past it makes him an inspiring figure. All he wants is the life of the mind and a friend to share it with, and a betrayal by Reece inadvertently puts him in a position where he suddenly has the influence to do it. The story of Zoe and Ele is one of knowing that the only thing of value either has in their lives (despite Ele’s love of tchotchkes) is each other. As such, they are willing to do anything for that love, because there’s no other point to living.

Gooch doesn’t abandon his central idea of how easily we betray each other in Under-Earth. Indeed, betrayal is literally a form of currency in the book. What’s different about Under-Earth is the sense that despite betrayal being a constant, it is still worthwhile to struggle for creating and preserving human connections. Gooch highlights this struggle through a variety of sub-genres. This is a prison story, first and foremost, but it’s also a heist story, an action story, and a mob story. No emotion is too oversized for Under-Earth, because there’s always so much at stake. Most importantly, this isn’t a book about escaping prison, because it can’t be done. The whole point of the book is accepting the limitations that we are dealt and working around them by reaching out to others for meaningful connections and intimacy.

The world isn’t fair, the justice system is flawed, capitalism pits people against each other and creates suffering while the elites profit. Giving up, like Jane did in Bottled, leads to narcissistic self-destruction. Malcolm in Under-Earth is such a remarkable character because of his capacity for forgiveness and empathy. He had much more cause to get revenge on Reece than Jane did on Natalie, yet he did something that Jane was unable to do: forgive himself. It is implied that he betrayed others just as Reece betrayed him, but he found the ability to forgive Reece because he acknowledged his own flawed humanity. Jane was unwilling to face up to who she really was, and so she could only perceive the betrayals of others and not her own.

In his body of work, taken as a whole, Gooch argues that finding cracks in the machine to nurture each other is our only chance at retaining our humanity. Forgiving betrayals is the only way to prevent them from escalating and to build connection. The concept of freedom without human connection is meaningless. The system may drive us to betray each other, but we still have the ability and choice to forgive and rebuild.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply