Taking its cues from the classical children’s fantasy narratives of C.S. Lewis, Roald Dahl, and yes, even Neil Gaiman, Australian cartoonist Campbell Whyte’s ambitious, sprawling, all-ages epic Home Time is admittedly something well outside my typical “comfort zone”. I mean, kids are kinda interesting in limited doses and all, but reading a story about them — much less one that clocks in, all told, at well over 400 pages, well — let’s just say that’s not a task that immediately lands itself atop my “to-do” list. Still, thinking it over, that probably provides this two-volume series a worthy and rigorous challenge: if it can interest even someone of a vaguely anti-natalist disposition such as myself, then surely it must have something going for it, right?

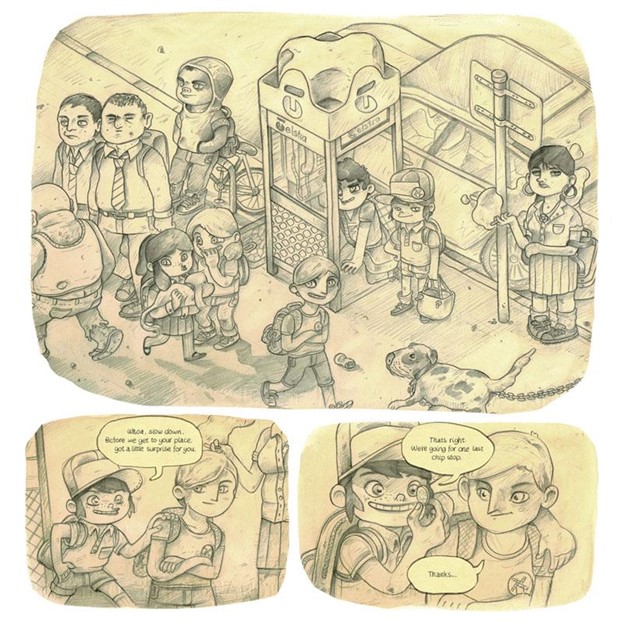

Right off the bat, the time, care, and sheer effort that has gone into crafting these books are readily apparent. Whyte illustrates the adventures of his tight youthful ensemble in a breathtaking array of styles, each representing a different character’s vantage point, and each fairly classified as “lavish”. Yet technical prowess alone isn’t enough to keep readers who have seen, to one degree or another, this kind of thing before on the hook. No, that takes a fair amount of heart, as well, and that’s what really separates Whyte’s work from his contemporaries in the noxiously over-crowded “YA” market.

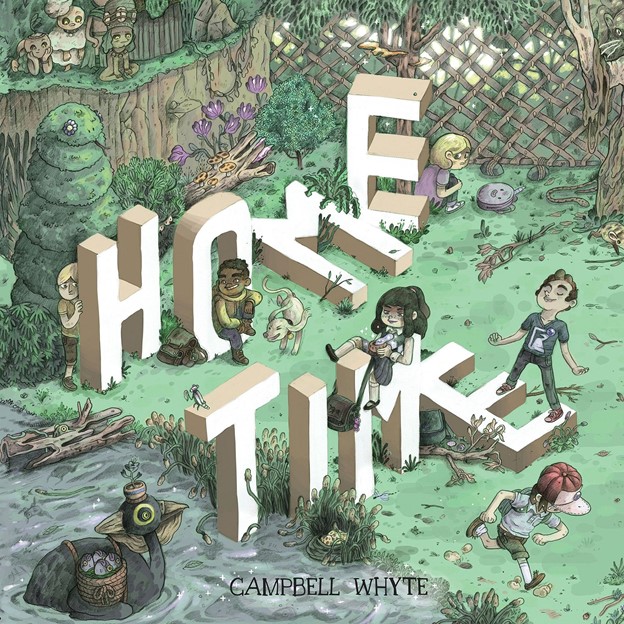

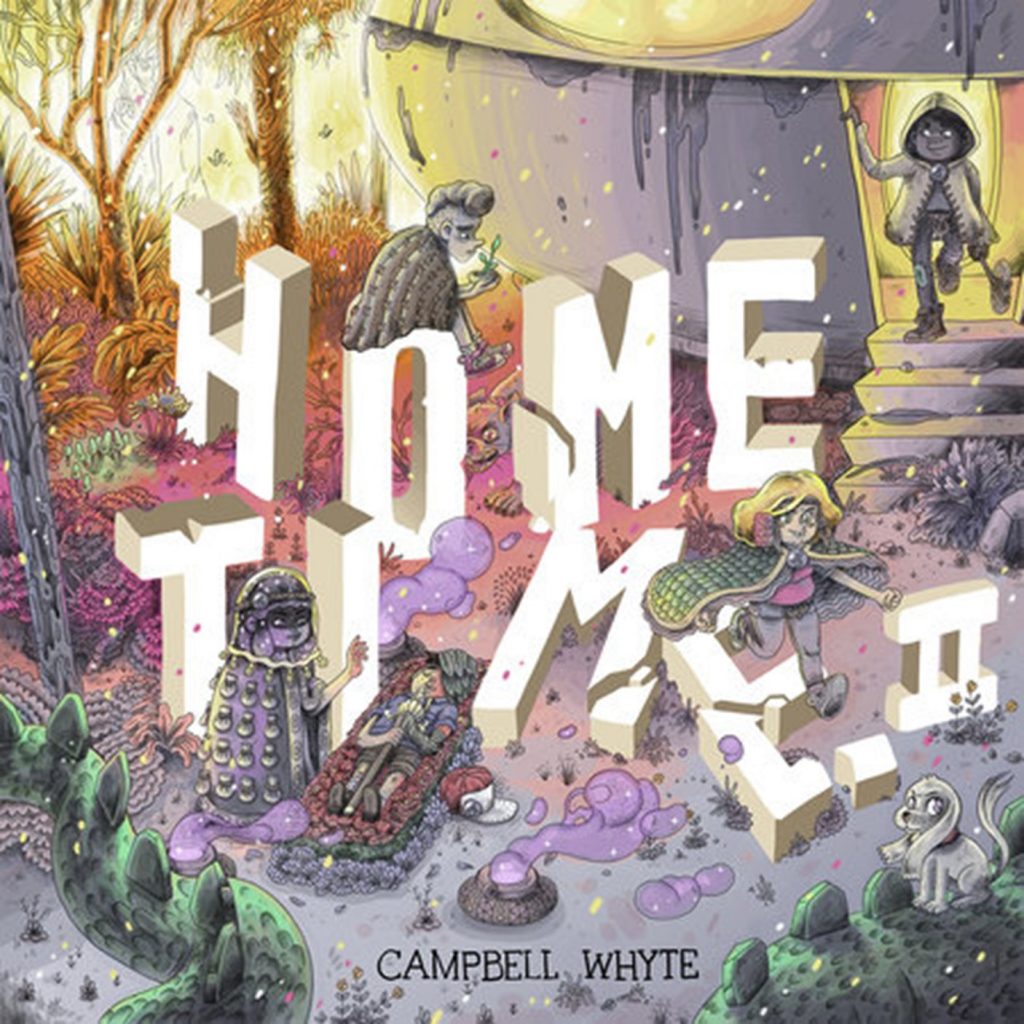

Whyte launched this Top Shelf-published series in 2017 with Home Time: Under The River and concluded it late last year with Home Time II: Beyond The Weaving. While hairs can — perhaps even should — be split over which volume was the more artistically successful of the two, reading them back-to-back as I did was a seamless experience that, hopefully, others will be able to replicate if a “bumper” collection is released at some point down the road. Simply stated, whether they’re in the “real” world or the magical realm of Peach Village that they find themselves transported to/potentially trapped within after falling into a river, the comings, goings, and occasional stationary languishing of twins Lilly and David and their friends are never less than completely immersive. While much of that is down to Whyte’s utterly sublime art, just as much credit needs to be given to his scripting and, in particular, his dialogue. Simply put, these characters both look and sound like real kids experiencing the joys and trepidations of their final summer before high school. And while growing up may be quite literally a more distant proposition for them than it is for their classmates given their unplanned trip to an ethereal imaginary fantasy-land populated by talking peaches, that split between wanting to grow up and wanting things to stay as there, a dichotomy that pretty much all children that age struggle with, is ever-present.

Indeed, just how badly or not the kids want to go back — as well as a heartfelt exploration of the reasons for or against the notion either way — is the central frisson of dramatic tension that Whyte plays for all it’s worth and probably then some. The wall around the Peach Village is ostensibly there to keep predators at bay, but are those predators biological or chronological? Whyte certainly isn’t afraid to play with the clock and to show readers the joys inherent in life simply stopping in its tracks. In fact, the segments where he puts narrative progression “on pause” and simply luxuriates in the richly-imagined environments that are, let’s face it, the creation of his own mind, are among my favorite sequences in the books. It takes some real confidence to eschew entirely the self-indulgence a reasonable person might assume these “breaks” are shot through with in favor of just stopping and smelling the roses — or whatever these plants are that the kids spend so much time trying to teach how to grow into shapes that might prove useful, amusing, or a little of both.

Of course, these children are still at an age where they’ll miss their families terribly, but that’s balanced with the sense of sheer wonder they have in their wonderful new surroundings. The locals viewing/mistaking them for divine spirits and affording them all the privileges that go with such a designation surely doesn’t hurt, either. And yet, for all their simple joys in singing, dancing, and tea brewing, among other low-key pleasures, there is a sense that they are losing themselves along with their concerns and worries as they acclimate to their new lives — until disaster strikes at the end of volume one and they are left looking for help, for medical care, for answers and, most especially, for a way home. It’s all fun and games until somebody gets hurt, as they say, and while the tonal shift from relaxed to urgent in the second book is stark in the extreme, there’s no arguing that narratively it makes perfect sense.

This isn’t to say that Whyte’s light, whimsical, humorous touch completely exits the proceedings. Rather, it’s woven into a larger, more complex, and more consequential dramatic tapestry. Fun and games, after all, would probably stop being both and slowly start to seem like work if they were all one’s time was consumed with. And while the allegorical implications of the various aspects of the kids’ journey are never anything less than absolutely obvious, the earnestness with which Whyte approaches them, and his noble refusal to give in to the cheap crutch that irony would offer, ensures that you’ll love these characters and their various “arcs,” both personal and collective, every bit as much as he obviously loves guiding us into and through their lives on levels practical as well as magical. And while I’m not a parent myself and may be getting a bit too long in the tooth to remember enough about my own youth to say whether or not childhood is imbued with any actual magic, the plain truth is that Home Time sure makes it seem like it is — and that alone not only makes it worth your time, it makes the time you spend with it feel more than just a bit wondrous.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply