In America, everyone has an equal say in public life and the democratic process. At least, that’s the story the country likes to tell about itself. In reality, some voices — including the wealthy and politically well-connected — clearly matter more than others. But what would it take to reshape the sclerotic institutions of the U.S. government so they serve ordinary people? Can politics be transformed by progressive organizing, or will the system always constrain even the most radical elected officials? And what does it look like when a cartoonist, of all people, tries to answer these questions? What does comics have to say about the mind-numbing intricacies of lobbying, legislation, committee meetings, and constituent services?

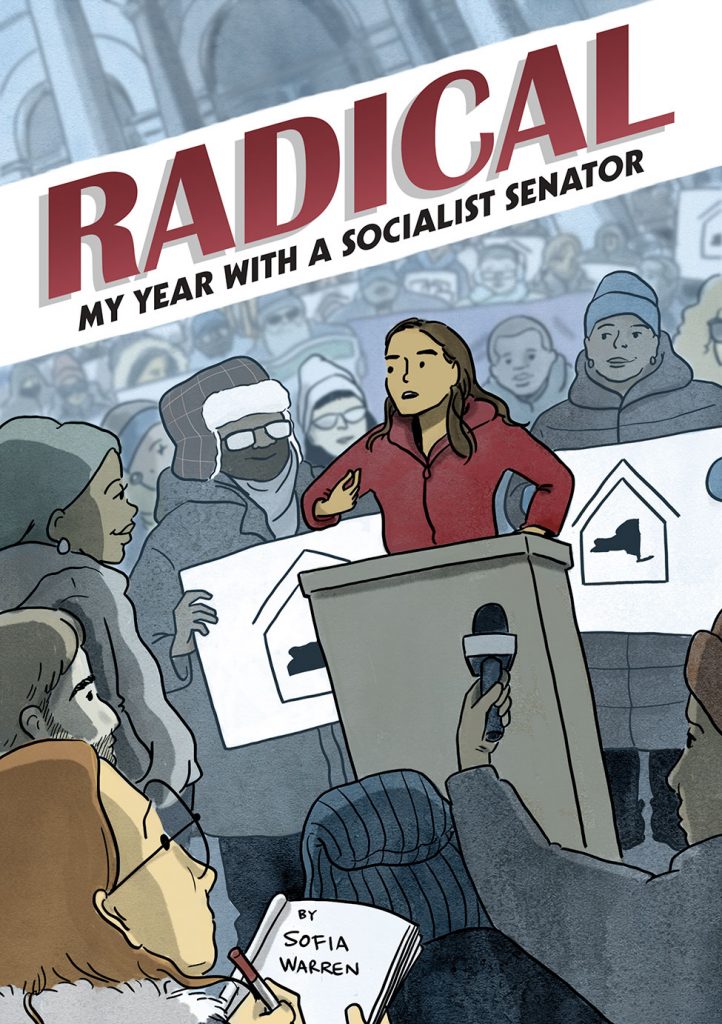

Quite a lot, it turns out. In her debut graphic memoir, Radical: My Year with a Socialist Senator (Top Shelf, 2022), cartoonist Sofia Warren undertakes the daunting task of illustrating and explaining what grassroots political activism looks like when it intersects with state politics. The sprawling, 300-page comic follows Warren as she embeds herself in the office of New York State Senator Julia Salazar, a democratic socialist first elected in 2018 on a platform of tenant rights and housing justice. The resulting narrative pits the freshman senator’s populist priorities against an entrenched political system that caters to the wishes of New York’s real estate industry.

The story is self-consciously filtered through Warren’s eyes, and she makes no claims to objectivity, though her status as a fly-on-the-wall outsider and her extensive use of recordings, notes, and sketches mean the book has more in common with comics journalism than with typical political tell-alls (in the book’s preface, Warren describes herself as an “independent interloper”). Her role is nicely captured by the book’s cover image: it prominently features Julia Salazar speaking at a rally, while Warren herself, notebook in hand, is unobtrusive, though still clearly visible, in the bottom-left corner. She looks up at Salazar, seeming to share the reader’s line of sight; Warren’s gaze is our gaze, and this is the book’s organizing principle.

Warren’s unassuming presence on the page serves as a useful stand-in for readers who might share her unfamiliarity with state politics. She begins as a disengaged, even apathetic citizen who is ashamed she didn’t volunteer for the Salazar campaign. “I was busy!” Warren writes. “I was trying, like so many before me, to Make it in New York as an Artist.” But as she watches Salazar and her staff settle into their new jobs, Warren absorbs the knowledge and language of Albany insiders alongside them.

In one key sequence, Warren demystifies the process behind New York’s enormous, $150 billion budget — “a massive, unwieldy package of bills” that literally towers above her avatar on the page. In theory, the budget process is democratic and open, with lengthy hearings where the public can give their input. In reality, crucial decisions are hammered out by “three men in a room,” slang for the three most powerful politicians in Albany: the Governer, the Speaker of the Assembly, and the Leader of the Senate. The process leaves Salazar and her staff frustrated and disillusioned. They watch, powerless, as important priorities like a tax on luxury housing developments are stripped at the behest of the real estate industry. Salazar herself, though she intends to vote against the budget in protest, is pressured by Senate leadership into supporting it anyway. For the socialist, it’s a setback both personal and political, and she breaks down crying on the Senate floor.

Radical is most effective at moments like these when Warren explores the obstacles in the way of Salazar’s most ambitious goals. The comic also finds its strongest visual language when illustrating the narrative’s antagonists. These include the real estate industry, represented not by actual human characters but by slightly grotesque drawings of empty suits with miniature skyscrapers for heads. The other enemy is Governor Andrew Cuomo, an intimidating and powerful politician who accepted millions of dollars in campaign funding from the real estate lobby. Cuomo is also not really a character in the book, though Warren at least gives him an actual face (“He keeps coming out looking like a zombie,” Warren quips in one meta-splash panel that depicts her various attempts to draw Cuomo). In one sequence, the Governor is depicted as a puppeteer manipulating lawmakers; in another, he appears as an intimidating giant who literally holds the fate of housing legislation in his hands.

Despite moments of visual creativity, Radical sometimes sags under the sheer number of words crammed onto its pages. Perhaps this was inevitable given the complexity of Warren’s subject matter, and her tendency to explain the intricacies of political maneuvering yields a better, more accurate picture of the legislative process than simplified illustrations (like, for example, the Schoolhouse Rock! approach to civics). But the narrative does devolve at times into a grueling series of talking heads.

Warren’s commitment to institutional storytelling also means she doesn’t spend much time obsessing over who Julia Salazar is as a person. Early in the book, Warren recounts a conversation she had with a friend about controversies that bedeviled Salazar’s election campaign, most of which centered on questions of identity (Was Salazar really an immigrant? Was she really Jewish? Did she actually grow up in a working-class household?). Warren seems to be wrestling with how much space she should devote to Salazar’s biographical details, and during that conversation, she asks a prescient question: “So, like… how much does Julia as an individual even matter?”

The answer is complicated. Salazar, on her own, can’t change the power structure of Albany or get money out of politics. But the people she brings with her to the Capitol do matter. A coalition of tenant advocates, working in coordination with her and other progressive lawmakers, does manage to outflank Cuomo’s attempts to sink their housing reforms. Near the end of Radical, Warren writes: “I didn’t focus on Julia’s past in this book because I told myself I wasn’t writing a biography. I wanted to write about government, and about a movement. … But if I were making a book about Julia, I might not do all that much differently. Because I can’t think of a better way to represent her than through the people around her.”

One of those people around Salazar is Warren herself. In the final three pages, she returns the focus to her own political education, constructing a microcosm of the journey she’s taken. Warren draws herself at a table, pen in hand, gazing out the window. Her narrative voice describes a potential future, one in which more socialists are elected to the New York statehouse. “I’m excited to watch what happens,” she says. But turn the page and Warren’s figure disappears. The comic’s final panel is unfinished and her pen lies abandoned on top of her notebook. Warren’s words — “Or maybe I’m done with just watching” — hint at a personal reshuffling of priorities. At first glance, the message seems clear: following Salazar has inspired Warren to get off the sidelines and get involved in political organizing. Perhaps she won’t run for office, but she’ll at least be out there knocking on doors, helping to get socialists elected.

Yet there is something tantalizingly ambiguous about Warren’s abandoned pen and notebook. After all, the claim that she has been “just watching” strikes me as inaccurate. Warren has been witnessing, learning, chronicling, and drawing, and while Radical may not have the tangible impact of a new housing law, it is a valuable picture of what politics is and also what it could be. Comics that explain the inner workings of government and expand our collective political imagination are both badly needed, and I hope the unfinished final panel represents, not a total transformation, but an opening of new possibilities for Warren’s sequential art and a space for new projects.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply