Élodie Durand’s Parenthesis is a graphic memoir relating several years of her life when she suffered from epilepsy. Thanks to her family’s recollections, she has reconstructed that time in her life as best as she can. Rather than avoiding the contradictions between her and her family’s memories of that time, she uses those contradictions to explore the slippery nature of memory itself. For Durand, that problem with memory also leads into how one defines a self, which, in her case, is also an artistic self. Ultimately, these questions encourage readers to look at the form of this work overall, as it’s unclear for much of the work if it’s fiction or memoir.

Early in the work, Durand references something that happened in her life, but she is vague about what it is. She avoids talking directly about her epilepsy, an approach that makes sense, given how little of that time she actively remembers, but she also admits throughout the work how often she ignored her illness at all. The reader, then, enters the book at a loss with what the narrator is talking about. There’s even the complication that the main character’s name is Judith, not Élodie, even though the back of the book describes it as a graphic memoir.

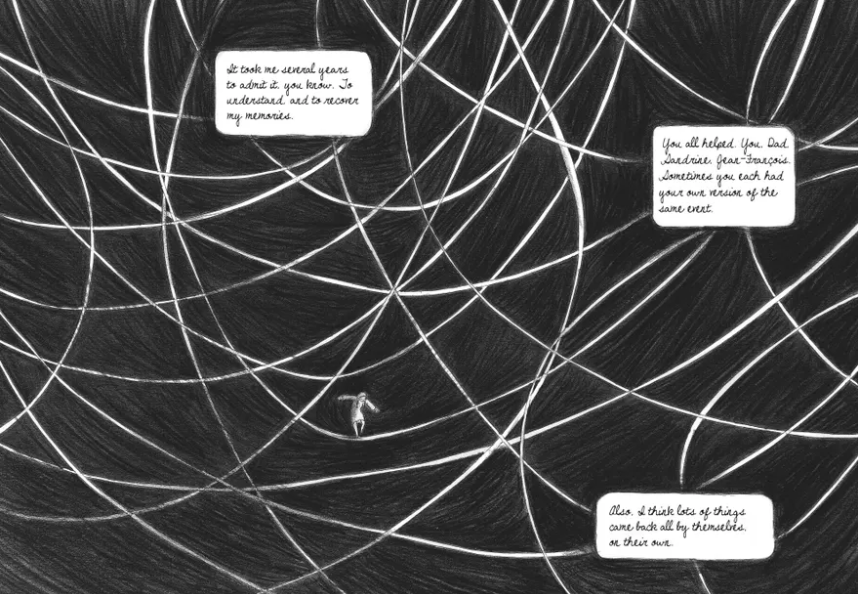

Durand creates this sense of uncertainty in the reader because it’s what she experienced with her epilepsy. In the same way that she isn’t sure exactly what happened, the reader also isn’t exactly sure. At one point late in the book, for example, she has one page devoted to her improvement. She makes comments such as, “I’d memorized the words to the song for choir, and also dance steps for salsa class,” I was counting better on the calculator and my fingers,” and “I held my own. In the end, it wasn’t hard” (194). However, on the facing page, she draws herself in the present of writing the book, seated with her parents, as they tell their version. Her mother begins by saying, “‘Wasn’t so hard?’ That’s not what you said back then. It was hard!” (195). Her father adds, “You don’t recall, but…You’d even say you’d never been sick” (195). By presenting her point of view as what happened, then countering with her parents’ version, Durand reminds the reader she’s an unreliable narrator, but also that all of our memories are not exactly what happened, sometimes not even close.

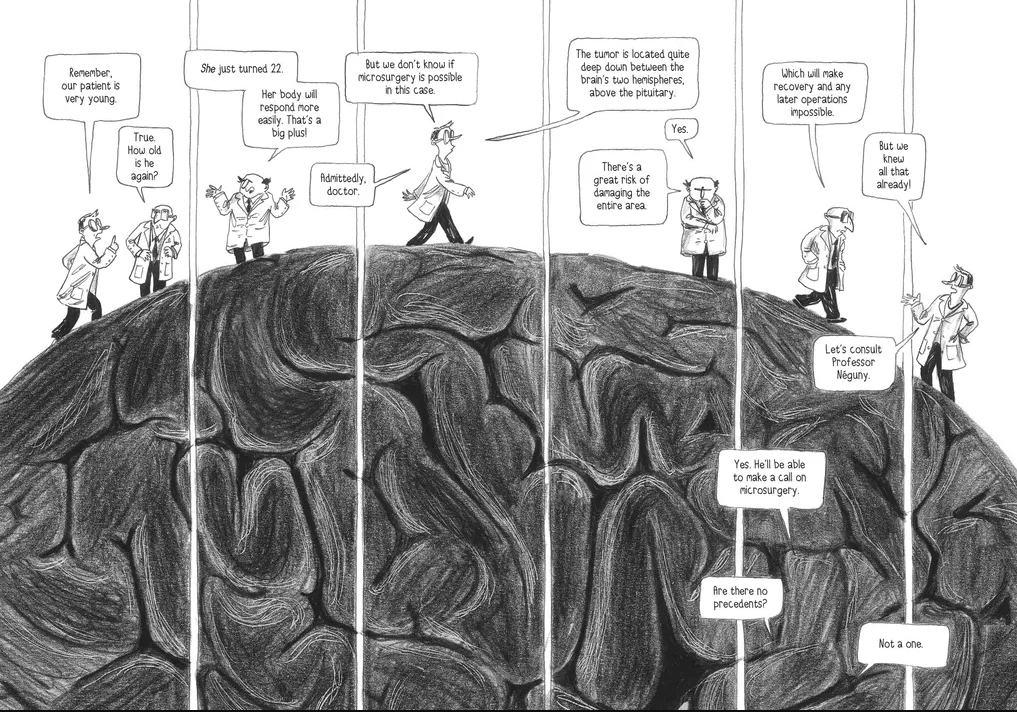

Lest the reader think her parents’ version is any more reliable, in fact, Durand uses her sister as another viewpoint that questions her parents’ telling. When her brain tumor is malignant, Durand presents a scene from the present where she is talking to her parents on the telephone, asking them how they felt about that news. They downplay their reaction, as the mother says, “There was nothing to say, nothing to do. Even the doctors didn’t know what to say to us. It wasn’t operable. They’d already told us that. We knew.” On the other end of the phone, Durand comments, “Sandrine said you were scared stiff. Babbling incoherently” (83). While the parents want to present themselves as calm, Sandrine’s presentation of them is the one the reader would expect with such news. The reader is left without a reality they can trust.

Not only is the reader unable to know whose version of events is reliable, but Durand can’t, either. That lack of knowledge leads her to question who she actually is, as memory plays such a strong role in our idea of selfhood. Early in the work, she quotes Luis Buñel, the Spanish surrealist filmmaker, saying, “Our memory is our coherence, our reason, our feeling, even our action. Without it, we are nothing”(22). Her artwork reinforces this theme throughout the book, as her scenes are more sketches than fully-developed, realistic portrayals of what happened. She draws her head as separate from her or larger-than-life, and when she is particularly suffering from her epilepsy, the drawings of her change from more realistic to almost monstrous (she even refers to her head as a monster at one point later in the book).

At times in the work, she even talks about feeling like somebody else. That view makes sense when she behaves differently than she would have before the epilepsy, but she also uses it when she discusses her denial of her illness. When she goes to the hospital for a biopsy of the tumor they have found, she says, “I was already sleeping a lot, way more than normal; I wouldn’t be able to go on like this. And yet, I was convinced I wasn’t sick. How can I explain? I must’ve been someone else…” (66). She draws pictures of herself breaking apart, or she uses the monster imagery as a way to show how the disease seems to be separate from her.

Given that she’s an artist and writer, though, Durand uses her work to help her make sense of what happened, both during the process and afterward. Early in the work, before the reader knows what Durand is struggling with, she writes, “For a while now, I’ve been drawing in a little black notebook, just for myself. I draw whatever goes through my head…quickly, without thinking. Sometimes I jot down the odd word…short sentences. I draw all the things I can’t understand. Everything I can’t put into words” (14). She follows that page—a fairly realistic portrayal of her walking into a room and drawing in that black notebook—with single-page sketches that look as if she drew them in a minute or two at most, they are mainly vague figures or images that convey an emotion, but nothing more. These stylized drawings reoccur throughout the book, as she leaves them in to show the reader the types of work she would produce to help her process her thoughts and emotions when she was struggling with memory and selfhood.

This book is her continued processing of this time in her life—the parenthesis of the title—that she has left by the end. She addresses it to her mother, as she is talking to her about how she felt throughout this time, while giving her parents’ and others’ points of view to counter what she has been able to remember. Near the end of the book, she tells her parents, “But talking about it [her illness] with you and Sandrine always helped me. It allowed me to recover all sorts of memories from before. And make connections in my head” (195). By the end of the book, she’s able to accept both her current limitations but also the time she was sick, which she had consistently denied. She comes into a sense of who she is as a person and an artist.

Finally, though, there is still the question of what is real or what actually happened. Because she uses her middle name to refer to herself throughout, I was repeatedly confused as to whether I was reading a graphic novel or graphic memoir. The blurb on the back of the book reinforces this contradiction, as it defines the work as a “graphic memoir,” but then says the work is “Based on the experiences of cartoonist Élodie Durand…” As a reader, then, I’m left wondering if I know what happened, which may be Durand’s point. I do believe that, by the end, she has truly accepted this awful time in her life and who she now is. She has worked to reconstruct, as best she can, who she was and what happened to her, and, in so doing, created the person who could produce this book, whatever category it fits in.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply