Don’t look now, but the “cultural moment” is having a “moment” of its own — which is either doubly ironic, entirely expected or, in keeping with the nature of the moment itself, a little bit of both.

Like one of the memes that both directly communicates and mercilessly minimizes said moment’s point and poignancy, this examination of where we are now has spread to all media, from the Hollywood blockbuster side of the cinematic ledger (Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther, Todd Phillips’ Joker), to arthouse screens (Olivia Wilde’s Booksmart, Joe Talbot’s The Last Black Man In San Francisco), to the once-vapid TV airwaves/cable wires (Damon Lindelof’s Watchmen, Bruce Miller’s The Handmaid’s Tale), to the printed page (Jia Tolentino’s Trick Mirror, Valeria Luiselli’s Lost Children Archive), the works of art and/or entertainment that define the collective socio-cultural-political landscape are primarily concerned with examining that landscape — even if they feature masked super-heroes or take place in dystopian futures. Being alive in the here and now, it would seem, is all about parsing meaning out of what that here and now is — or, at the very least, what it represents.

A true post-modernist might argue that those are the same things since they tend to hew to a belief that meaning itself is dead, but that’s probably outside the scope of a review such as this to properly analyze — what this critic finds both curious and, to at least a certain extent, heartening, is that this particular “cultural moment” seems to have either moved beyond, or at least temporarily shelved, post-modernism. The post-2016 reality of making it pretty goddamn clear that “nothing matters and what if it did?” is, essentially, a recipe for non-survival on a mass scale. Of course, our actions have meaning, not only to ourselves and those closest to us, but often on a scale we’d never imagined. After all, if just a small handful of people hadn’t thought to themselves “what the fuck, I’ll roll the dice” as they entered the voting booth last time around, we likely wouldn’t be in this mess in the first place. Comics, to get to the point here, haven’t eschewed this simultaneous analysis of, and response to, the here and now, and in the last few years works such as Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina, Michael DeForge’s Brat, and any number of others have risen to the top of both “most-talked-about” and “most-awarded” lists by providing unflinching examinations of life in what has broadly — but hopefully mistakenly — been referred to as a “post-truth world.” And if there’s probably one talent, one voice, uniquely equipped to provide an honest and brave appraisal of this turbulent era, it’s Eleanor Davis.

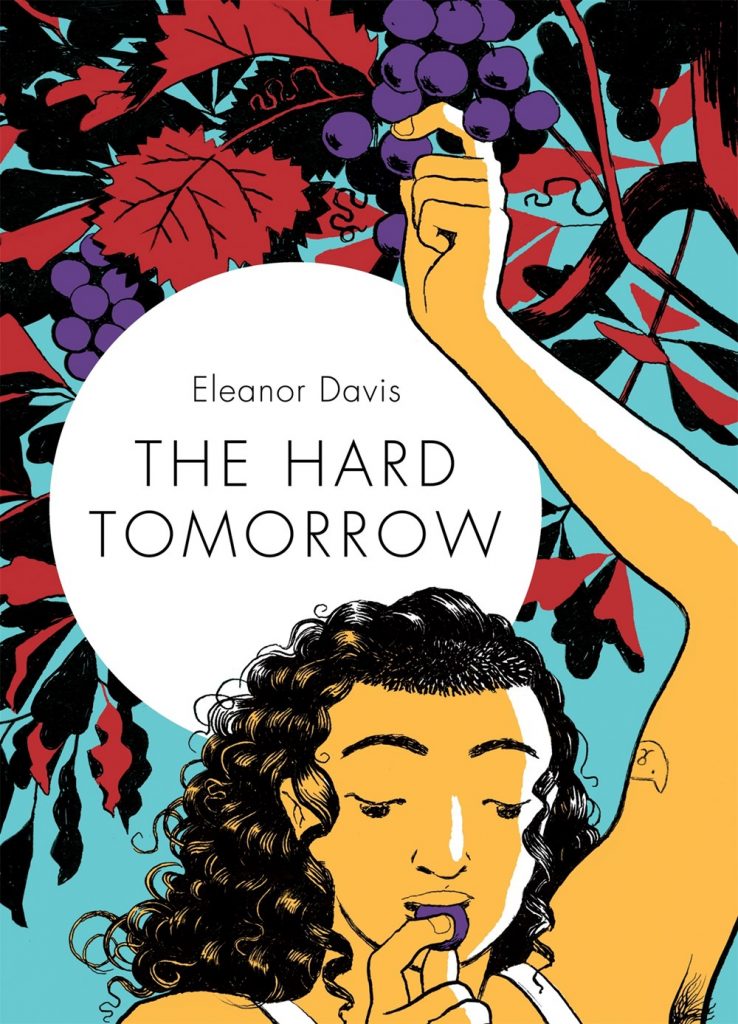

No stranger to tackling the big questions (see last year’s Why Art?) nor to personalizing the political (see 2017’s You & A Bike & A Road), Davis’ latest, the Drawn+Quarterly-published hardback graphic novel The Hard Tomorrow, is pretty clearly the book that she’s been building up to for some time: a comprehensive stock-taking of where our nation is, where the people within it are, and what the potential consequences of not changing course are, the latter of which is ably facilitated by the wise choice to set her narrative in the not-too-distant future.

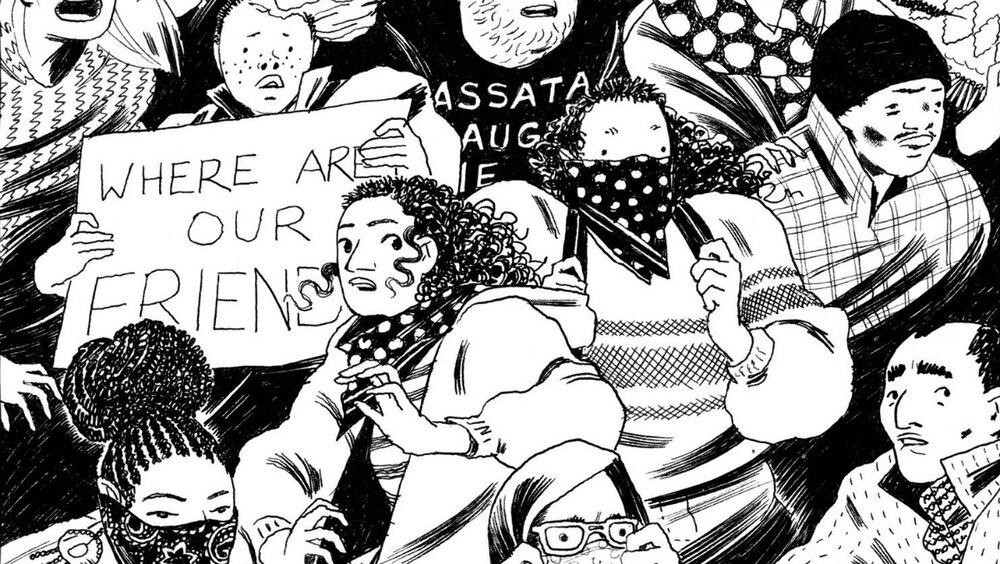

Don’t let that fool you, though — things have escalated slightly in The Hard Tomorrow (cops wear full riot gear that conceals their identities and, crucially, badge numbers, mass deportations would seem to be in full effect, political opposition is ground under a firmer boot-heel than it usually is, a possible economic downturn has made the idea of people living out of their vehicles apparently more commonplace than it is right now), but every proto-dystopian scenario Davis brings into the fold of The Hard Tomorrow is an entirely logical extrapolation of things as they stand presently. This, however, is no mere “cautionary tale,” and that’s where things get really interesting.

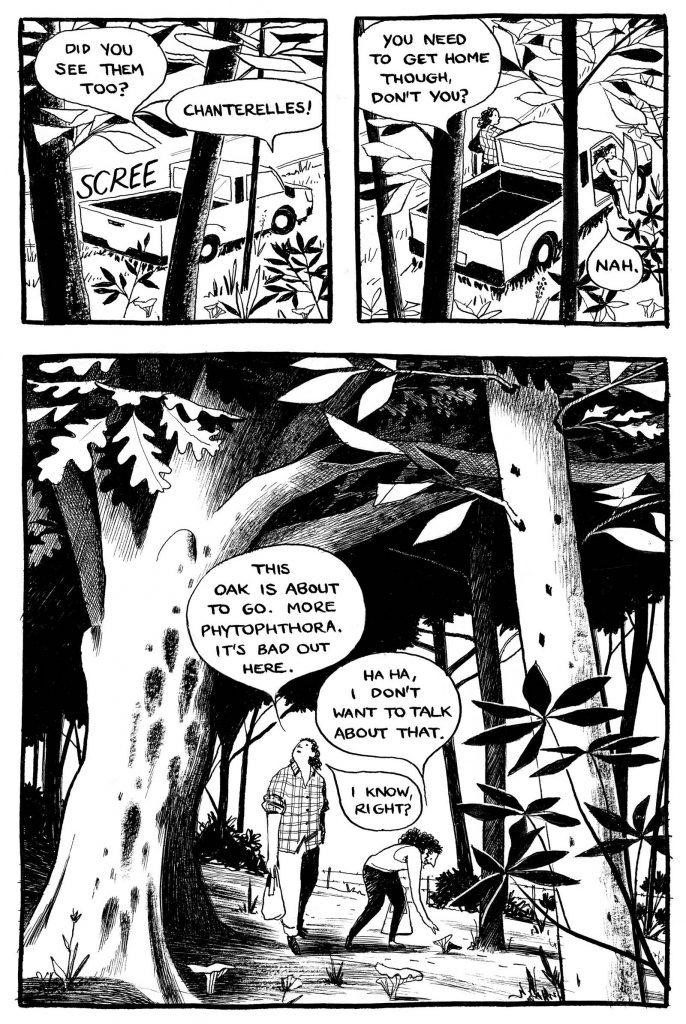

Protagonist Hannah is as fully-realized a character as you’re likely to find in graphic fiction. She’s a caregiver, anti-fascist activist, and the primary water-carrier in her relationship with her boyfriend, Johnny, a pot dealer who probably enjoys sampling his product a bit too much. It’s in the quiet juggling of these multiple roles with something akin to as much grace as possible that Hannah’s inner strength shines through, and that her desire to start a family despite troubles both macro and micro makes both logical and emotional sense.

Davis’ primary mode of communication in The Hard Tomorrow this is visual — her sparse dialogue is uniformly, even awe-inspiringly, perfect no matter the scenario or interaction, but it’s her exquisitely-crafted cartooning, which privileges expression and reaction above all and does so in ways both obvious (fluid “action” scenes depicting brutal police crackdowns) and less so (the subtleties of her characters’ facial features changing in reaction to small events, or even a word, is breathtaking) that does almost all of the metaphorical “heavy lifting” here, to the point where even a wordless version of this story would make a kind of intuitive sense to most readers.

All of which begs the question — is The Hard Tomorrow more felt than it is explicitly understood? And the genius — a term I don’t invoke lightly — of Davis lies not so much in the fact that this question can be glibly answered with “both,” as it does in negating and particular distinction between the two while appealing to the head and heart simultaneously. The book is smartly constructed, to be sure, but it’s both written and illustrated with so much heart that it can afford to be both generous to, and critical of, each of its characters without bringing their creator’s love of them into question at any point.

That head/heart balance is wonderfully, joyously, obliterated by The Hard Tomorrow‘s final pages, though, a series of double-page spread of Eleanor and Johnny’s baby opening its eyes for the first time, and it’s here that Davis makes her boldest statement of all in terms of providing a road map out of our current societal quagmire — love and life are not just the way to a better future, they are the future. And while that may sound corny and simplistic to any reader going into The Hard Tomorrow, by the time it’s over, you’ll not only be convinced it’s absolutely true, you’ll be reminded that it’s the only absolute truth.

READ MORE

Leave a Reply