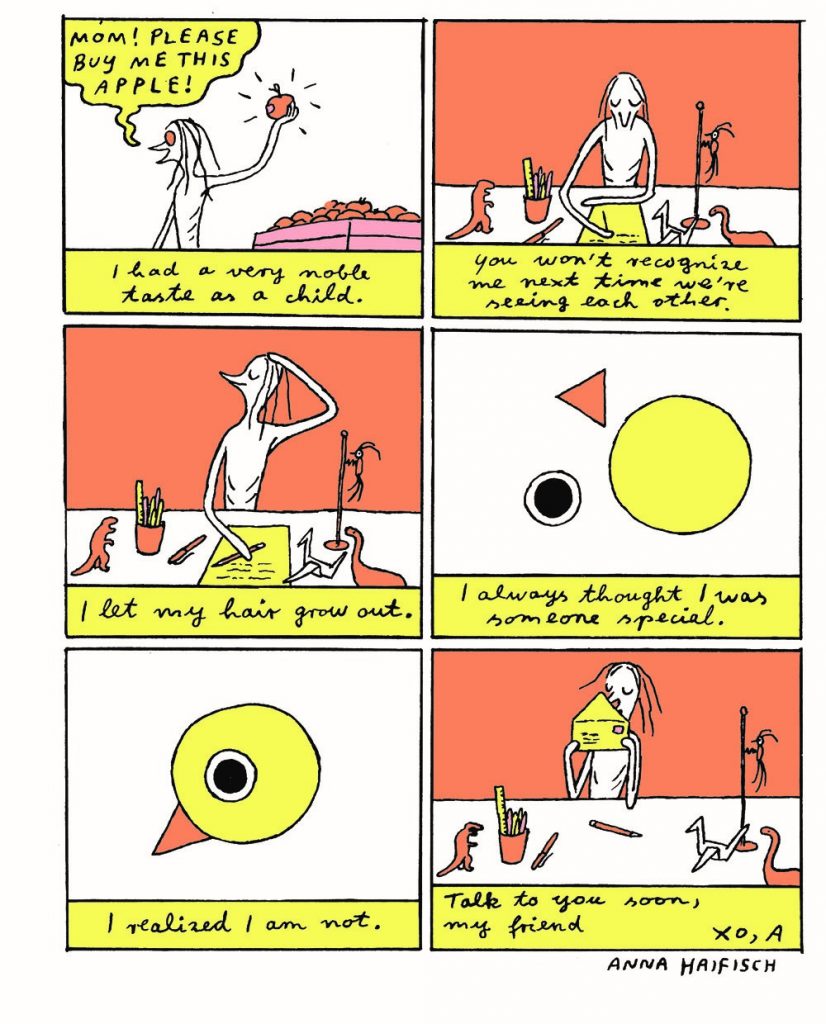

Over the last few days, my colleagues at SOLRAD have grappled with Anna Haifisch’s Artist. This willowy, fragile bird is the center of two collections of comics, both published by Breakdown Press. He is also the center of Haifisch’s name recognition in the USA via the now-defunct Vice Comics. But who or what the Artist is has been up for debate; is he, like Daniel Elkin or Ryan Carey suggests, a stand-in for Haifisch? Or, as Sara Jewell posits, the avatar of “artists” on which Haifisch projects societal structures? As a character with no name other than “Artist,” created by an artist, either of these interpretations seems reasonable.

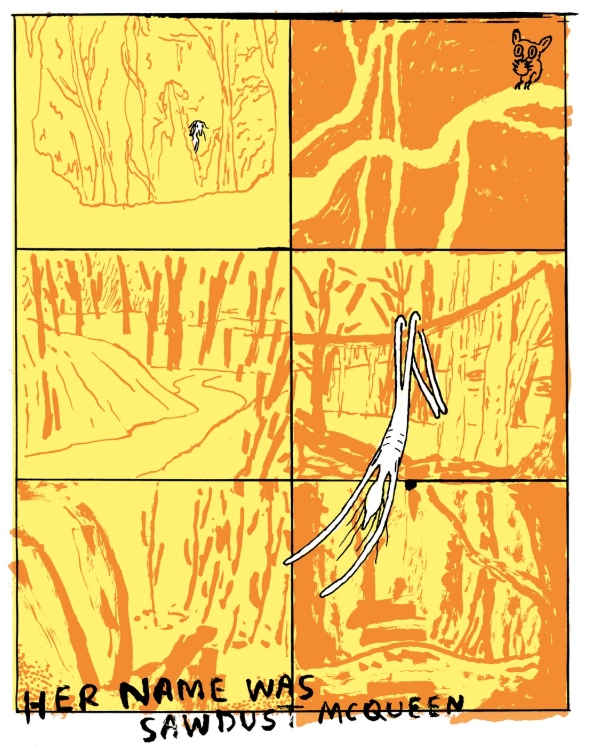

Haifisch has made a lot of art that examines the political and the societal, but rather than something overtly symbolic or self-reflecting, I see the Artist as a character that Haifisch uses to explore the world. While her work in comics like “The Hall of the Bright Carvings,” Drifter, and The Mouse Glass explore the world’s nastiness through the lens of funny animals, the Artist is something different. Rather than being global, The Artist and The Artist: The Circle of Life are very specific to an experience of the “art world.” That specificity gives Haifisch a way to explore while still being thoroughly in her lived experience.

Unlike my colleagues, I don’t think the Artist is an avatar for artists generally or for Haifisch herself; rather, I see the Artist as Haifisch’s version of Charlie Chaplin’s “The Tramp,” a character that Chaplin used to create the first international movie star. Chaplin’s Tramp is a melancholic bow-legged bumbler with a good heart. He moves through the world aimlessly and is thwarted by the machinations of those in power. He has a hard time finding love and peace and is often beset by failure. The Tramp is seen by others as a meddler or a vagabond, and he often is dismissed or jailed for things outside of his control. The world isn’t really that interested in seeing him for who he is, but for what he represents – lack of capital, lack of status, and lack of the things that motivate the bourgeoisie.

If you took my description of Chaplin’s Tramp and substituted Haifisch’s Artist, you’d find that both fit the description. Like Chaplin’s character and movies, the Artist in these comics is fragile, often foolish, and at distance from the world. He longs for acceptance and normalcy, but can never have it. And like the Tramp, Haifisch’s Artist is a dreamer, a person looking for his slice of the pie, no matter how small that slice might be.

Much like those early silent films, Haifisch’s Artist lives in a world that is melodramatic. Haifisch gives readers the chance to experience the in-fighting and back-biting of the art world through The Artist but exaggerates it nearly to the point of absurdity. Moments in The Artist: The Circle of Life like the Artist’s residency in a snowy wasteland or experience with an art collector are Haifisch using the stories of other artists and old societal expectations (e.g. the reclusive and crazy genius, the tortured soul, the brilliant and enigmatic taste-maker) of “the artist” and turning them into an idealized drama. Like Chaplin’s movies, Haifisch’s comics can also deliver a punch when necessary.

That drama is the ideal place for a character like the Artist to live because it amplifies what we already feel about our own lives. The silliness of the situations the Artist finds himself in are similar to those of Chaplin’s Tramp, and in that silliness, readers will find a shared grimace, a wink and a nod from Haifisch. The stories of the Artist reflect the world we live in: the desire for safety and normalcy; the imposter syndrome we have when we compare our work to another person’s; the fear we have of the unknown; the lies we tell other to make them like (or love) us.

One of the things that separates Haifisch’s Artist from Chaplin’s Tramp, though, is the sense that Haifisch is always pushing her stories to exist on the razor’s edge; there is something sadistic about what The Artist goes through. While it’s clear that she’s quite fond of the character, Haifisch always seems to want to turn up the noise, to make it a little harder for him. At times his suffering is extraordinarily detailed. The Artist: The Circle of Life feels like a guitar string that’s being tightened too tight, moving towards but not quite reaching the point where it either frays or snaps. Every situation in the book feels as absurd as it can get without going too far. Haifisch wants to know – how can I make this funnier and sadder at the same time? How much can I push this character? How far can I take this story before it becomes maudlin or ironic? Balancing these two demands is where Haifisch finds her strength, and it is the reason why The Artist and The Artist: The Circle of Life are such successful works. These comics present the world to us in ways that seem foreign but familiar, funny but heart-wrenching.

Despite how sadistic her stories can get, though, there’s also something intensely vulnerable in Haifisch’s writing of the Artist. Just like Charlie Chaplin’s portrayal of the Tramp, Haifisch’s character serves up comedy and pathos as both an outsider in a strange and unforgiving world, and as an everyman that the reader can relate to and cheer for. We love the Artist, that scallywag, and we want him to love us too.

If I think I can say anything about Haifish’s Artist, it’s that he exists as a counterpoint to the humdrum of the average day. He, like Chaplin’s Tramp before him, exists outside of traditional systems of capitalism and wage-based work. While the Tramp sometimes tries to play along with the regular world, it always ends in failure or setback. Haifisch’s Artist is the same; his path outside of this traditional bourgeois life experience is bound to cause him suffering, but can also be quite beautiful. The Artist, whose version of that world is even more strange than our own, can find fulfillment in a good drawing of a snake.

What’s telling about Haifisch’s The Artist and The Artist: The Circle of Life is how the rest of the world sees the Artist. The “outside world” finds his behavior off-putting, even absurd, but simultaneously demands this kind of behavior from him. The joy in The Artist is knowing that he will continue along off the beaten path, even if it will sometimes bring him pain. Making the Tramp or the Artist exist in the spaces where they cannot will always lead to the same thing; the Tramp walking down the road into the sunset, or the Artist drawing another snake. When the Artist leaves the ordinary world of taking tea with his grandmother and “ordering housewares like a decent citizen,” and goes back to the art store, the reader feels the thrill of release – the truth is that Haifisch’s Artist was always meant to be an artist, just as Chaplin’s Tramp was always meant to be a tramp.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply