In one of the comic vignettes in the middle of Anna Haifisch’s The Artist: The Circle of Life, the eponymous artist, an attenuated bird, reluctantly goes to dinner with his uncle, an ostrich. Uncle Ostrich is a philistine who talks down to Haifisch’s Artist, and at one point dispenses the bromide “Art should be beautiful – cause life is beautiful!” There are many assumptions to unpack embedded in this statement about the purpose and function of art: whether art does or should mirror lived experience, whether its purpose is – or is only – to be aesthetically pleasing, and what a universal aesthetic ideal would even look like, But, chiefly, it assumes the question of whether what we refer to using the term “art” is monolithic. However, The Artist: The Circle of Life is more interested in where the person of the artist themself might be materially situated, somewhere beneath these lofty questions about what they produce. If society defines the value of the artist in terms of their notoriety, either upon an untouchable pedestal or isolated in a garret, it is then free not to dirty its hands with questions about the artist’s survival and human condition.

It is difficult to talk about Haifisch’s character apart from the figure of the artist as it is understood culturally, socially, and historically, since Haifisch gives her protagonist no name apart from “Artist”. She frequently uses him to play out satire and commentary that feels separate from the more narrative vignettes in which he is characterized, however fleetingly, in the context to his home, relationships, and avian attributes. The Artist himself, hazily reminiscent of an emaciated version of Higgs’ “Moonbird”, implicitly suggests the collection’s interest in the slippage between artists and the prevailing stereotypes: the starving artist, the tortured artist, the flamboyant megalomaniac. Haifisch wants her audience to consider the ways in which the flawed cultural understanding of the artistic persona is both reductive and harmful to people who make art, and how the devaluation or arbitrary valuation of the arts in a system of commerce has nonetheless forced artists to try and capitalize on the mystique of persona.

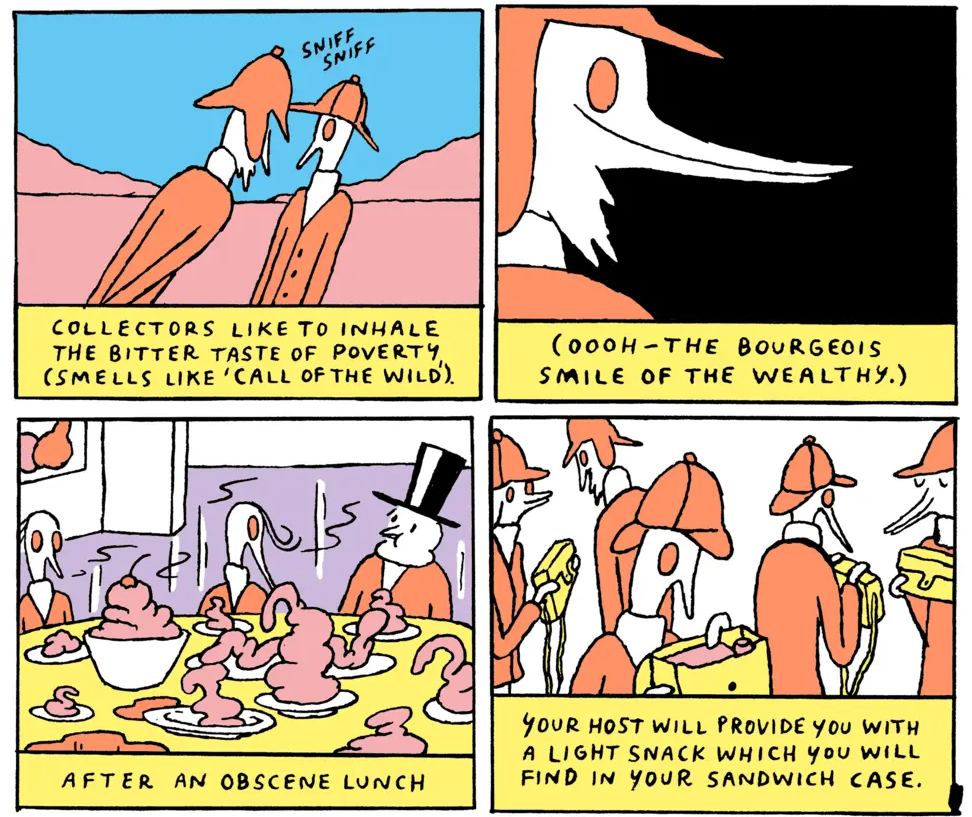

Numerous episodes in The Artist: The Circle of Life highlight the deleterious effect of the romanticized artistic persona on the Artist, insofar as it increases his sense of alienation from others, traced back to his childhood decision to “become an artist” with little understanding of what this actually entails. “A good person can’t be a bad artist, don’t you think?” he asks an art friend doubtfully in adulthood. In a letter to a friend while convalescing at home following his breakdown, he writes “I had a very noble taste as a child. You won’t recognize me the next time we’re seeing each other…I always thought I was someone special. I realized I am not.” The Artist finds the needs of his body and mind incompatible with the romantic ideal of the artistic persona, whose misery is supposed to be a creative wellspring and whose survival needs are deprioritized upon the altar of the all-important work of creative production. The expectation is that an artist live by a kind of inversion of Maslow’s pyramid, throwing himself upon the mercy of exposure and hoping that patrons and benefactors will find him deserving.

Resolving thus to lead a more virtuous life founded on ordinariness and normalcy, the Artist attempts online shopping, tea with his grandmother, and croquet, only to be lured back by the siren call of a hobby shop’s paints. In a later episode, Haifisch imagines the criminalization of art, the Artist and other artists jailed not for any specific iconoclasm but for their ill fit into the social structure. They’re put away for “disturbing the peace” with “eccentric screeching, loitering and prowling, bizarre vandalism, art rage and whatnot.”

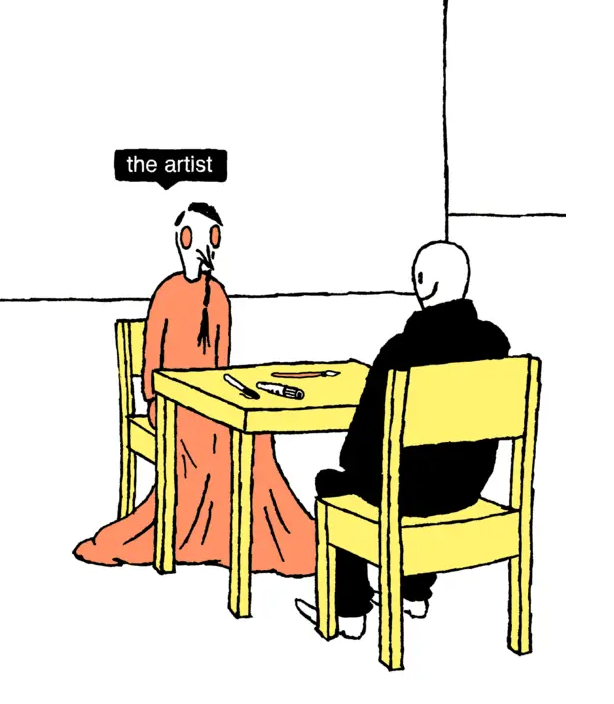

In the first of a few episodes that formally challenge the understanding of comics as a silent medium, “The Artist’s YouTube Haul and Tutorial Videos” links to an actual supplementary YouTube video on Haifisch’s website. The episode’s introductory cover image casts Haifisch’s bird Artist as Marina Abramović during her tenure sitting across from viewers at MoMA during her 2010 retrospective, as part of a grueling performance piece entitled The Artist is Present. Abramović’s presence during this retrospective challenged the invisibility of the artist in the museum context, where art objects are most frequently viewed at a distance from their creators; viewers may or may not choose to contextualize them by reading labels. However, Abramović’s performance did little to humanize her and, in some ways, framed her as an inviolable statue with no material needs – a 66-year-old woman sitting motionless and silent in a wooden chair for 7-10 hours a day, over a period of months, foregoing food, water, rest, and bathroom breaks during her seated time, reduced to an embodied gaze.

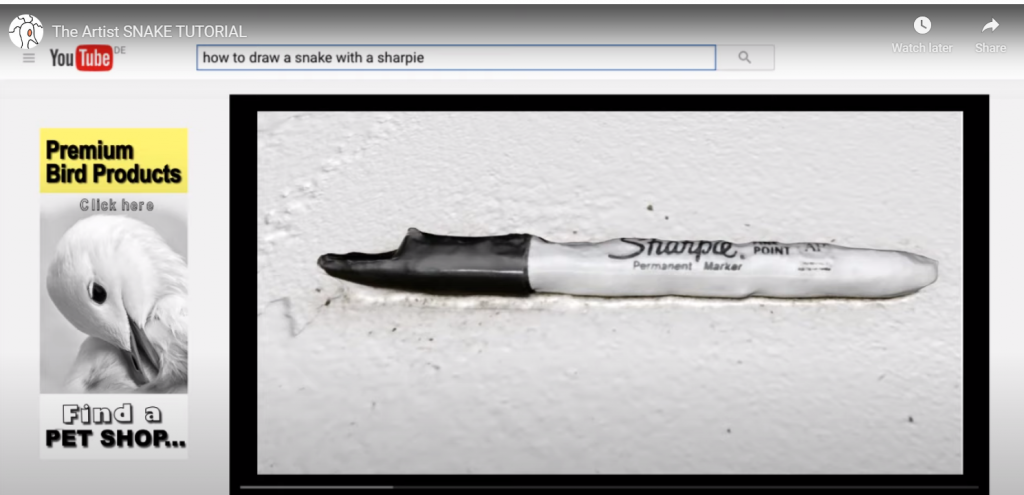

In “The Artist’s YouTube Haul and Tutorial Videos,” the Artist excitedly unboxes brushes “made with Russian weasel hair plucked only in winter time”, a Victorian-style frame, pens purchased for the mere reason that there’s “a cute seahorse on the package”, and sharpies. In this video, the Artist is implicated in the commodification of the artistic persona through the when it is inferred that the purchase of rarefied, cute or specialized tools is a prerequisite for making art. Significantly, he is not shown actually using any of these products. However, the comic of the haul video differs from the linked YouTube video. The 39-second linked video is entitled “how to draw a snake with a sharpie.” Visually its effect is one of infinite recursion: a video within video. Speaking with the “wah wah” gibberish sound from Peanuts, the Artist happily inhales the fragrance of a beat-up sharpie marker, and demonstrates his process of drawing one of his snake portraits, the subject that consumes him most over the course of the book. The video ends with a close-up photo of what might be the world’s most banged-up sharpie. Thus, it stands in sharp contrast to the comic, demonstrating that a simple tool, not newly bought, is the Artist’s preferred medium. It simultaneously strives to demystify the artistic process and make drawing accessible to anyone through a guileless presentation of process.

In the book, the internet remains a fraught landscape for the Artist, whose breakdown follows him bemoaning his lack of productivity compared to the apparent output of another creator on Instagram. Despite his frustration with his own output in comparison, he cannot help but feel tenderly towards what he has created, even if it can’t be neatly packaged as a social media post demonstrating his virtue and worthiness as predicated on his productivity.

Elsewhere, in an episode entitled “The Artist’s Lifestyle”, Haifisch parodies the Lifestyle magazine profile that employs the pretext of taking you through a personality’s typical day as a vehicle for advertisements. We see the Artist drinking a “mouth-watering detox kale smoothie” in a Valentino bathrobe, doing yoga on an Issey Miyake mat, and decorating his pencil case with leftover Chanel ribbons. This carefree profligacy contradicts Haifisch’s usual rendering of the character poring over his drawings in a spartan one-room apartment. With the artist here framed as an influencer, the ritual of his day becomes a performance facilitated by designer products upon which the mysterious practice of his art depends.

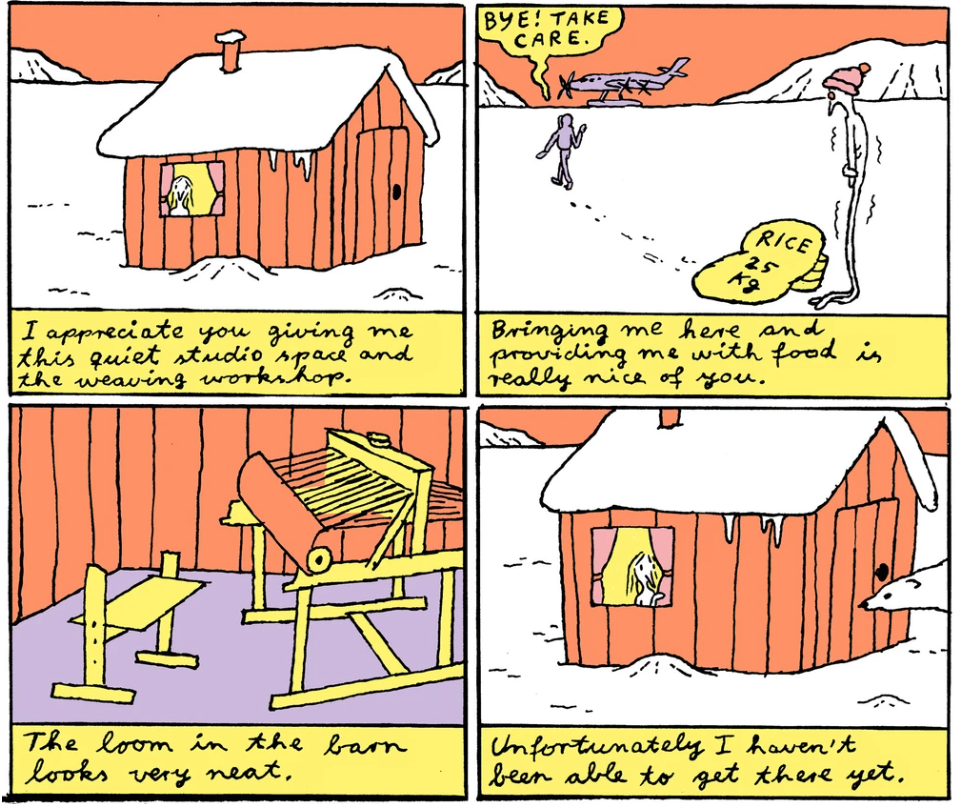

In a striking dichotomy to “The Artist’s Lifestyle,” “The Artist’s Residency” chronicles the ignominious death of the Artist in a snowy wilderness, having struck out from a tiny residency cottage in desperation after exhausting the insufficient supplies provided by the residency foundation. Even an organization supposedly devoted to the betterment of the Artist so that he can produce his work is unwilling or unable to adequately pay him the minimum wage of bare survival in the form of a satisfactory amount of rice and cod liver oil. Meanwhile, in a letter preceding his death upon the snow, the Artist frets: “I don’t want to sound unthankful or something…”

The book’s final episode points again to supplemental multimedia, its bright yellow-and-orange tableau intended to be accompanied by a linked piece of music, Sorority’s “Sawdust McQueen”. The pale figure of the Artist finally returns to the solitary beauty of the natural world, glimpsed in his childhood National Geographic many episodes before, when he lamented “Oh world, where did all the happiness go?”. He swings through the trees to the chords of the song, the text of the lyrics bridging panels and overlaying darkly upon the warm colors of each grid. The song ends on a note of betrayal as the artist abruptly fells a tree with a chainsaw; “I always thought trees were our friends…they’re not our friends.” Haifisch leaves it for the audience to guess what the trees represent.

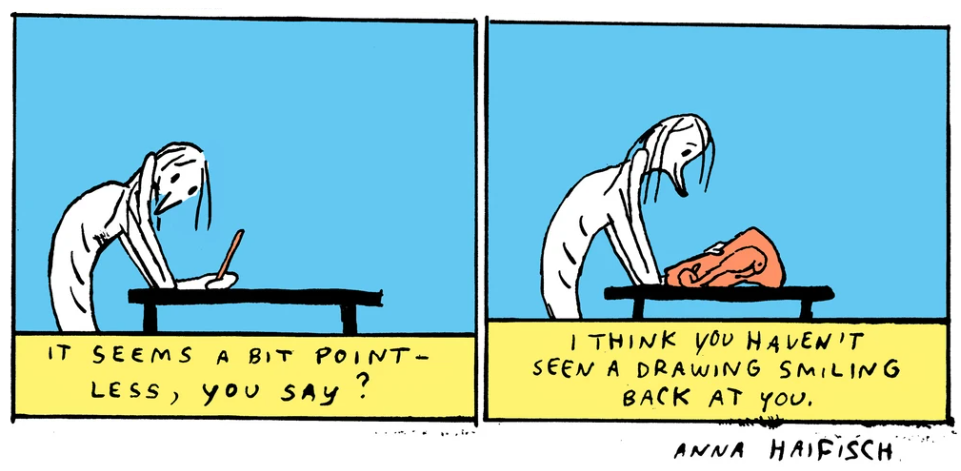

For all of its cynicism towards the art world and the hardscrabble struggle to make any kind of career out of a creative pursuit, The Artist: The Circle of Life also takes moments to dwell in the private sublimity of the creative act and the subsequent experience of art. Beyond money, accolades, social media likes, accoutrements, there is an ineffable satisfaction for the Artist in the birth of a new snake upon the fickle page. This satisfaction, perhaps occasionally as sharp and poignant as it might have been in the realm of childhood, still occasionally makes itself felt, in whatever spaces life leaves for it. It is intentionally ironic that this moment hearkens back to the childhood joy of creation unfettered by the concerns of adult survival, denuded of any persona or affectation.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply