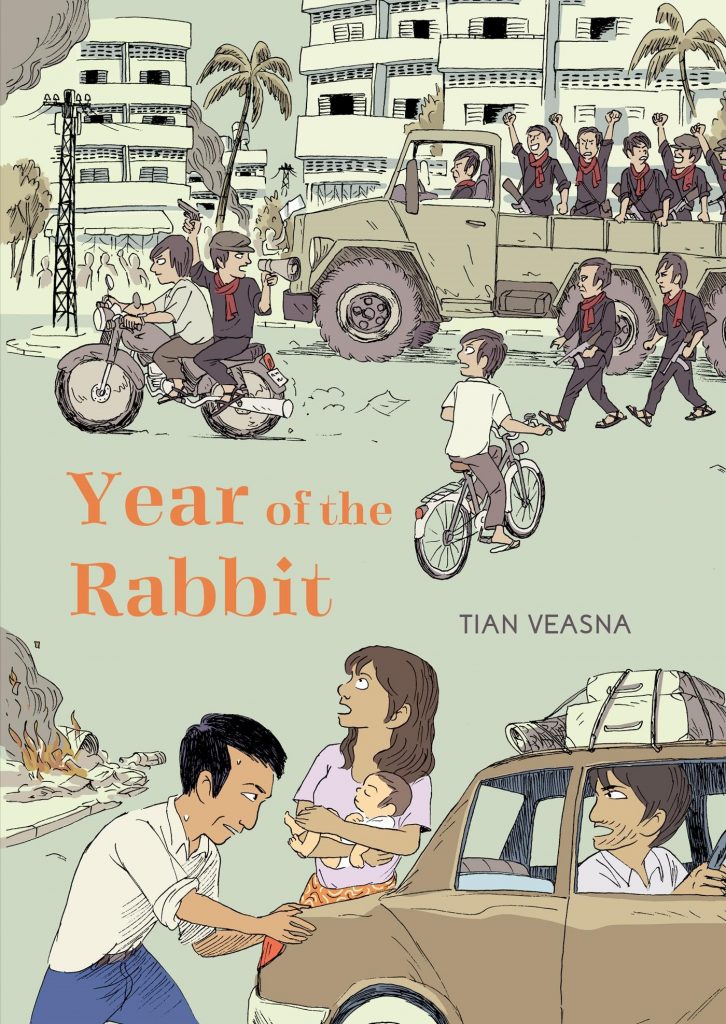

Equal parts historical labor and labor of love, cartoonist Tian Veasna makes the political personal in a way few can match with his new graphic novel Year Of The Rabbit (Drawn+Quarterly, 2020) because, for him, there’s truly no separation between the two. His story — fragmented by design to emphasize the fractured lives of its sprawling family ensemble — is the story of one extended group of relatives, namely Veasna’s own, but it’s also the story of a country and its descent into fascist brutality. It’s about what happens when “it can’t happen here” does, in fact, happen, and, as such, well — who are we kidding? It’s also something of a cautionary tale that likely couldn’t come at a more appropriate time given the radical authoritarian leanings of prominent world leaders in Brazil, the Philippines, the UK and, most infamously, right here in the US.

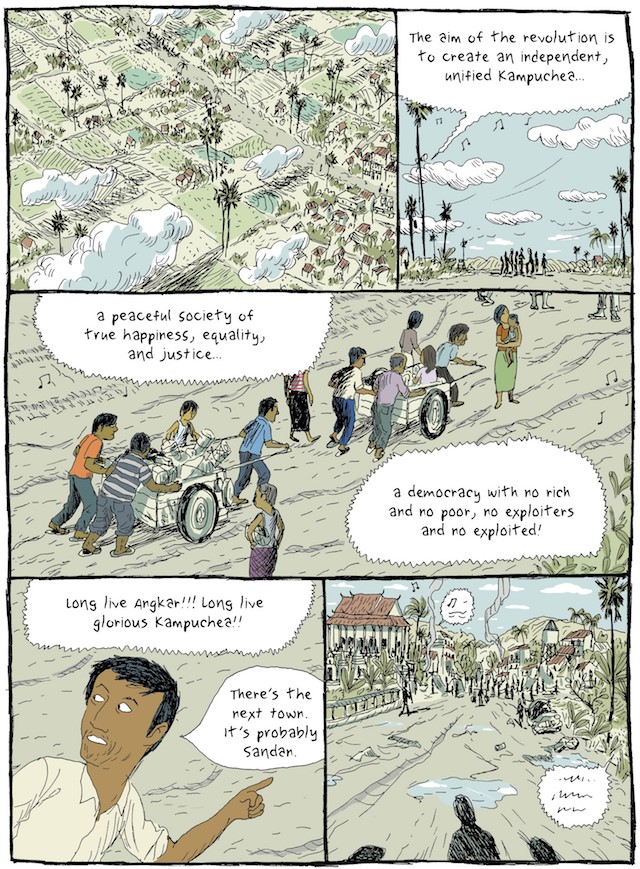

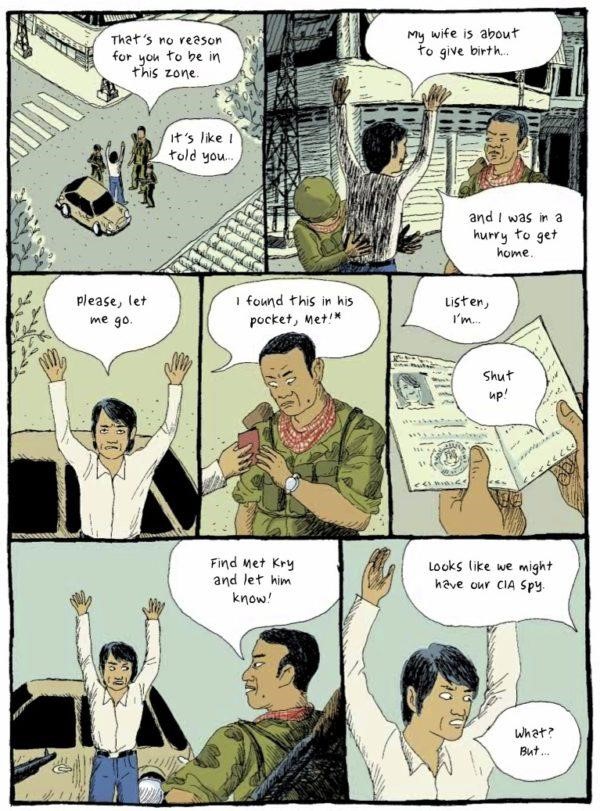

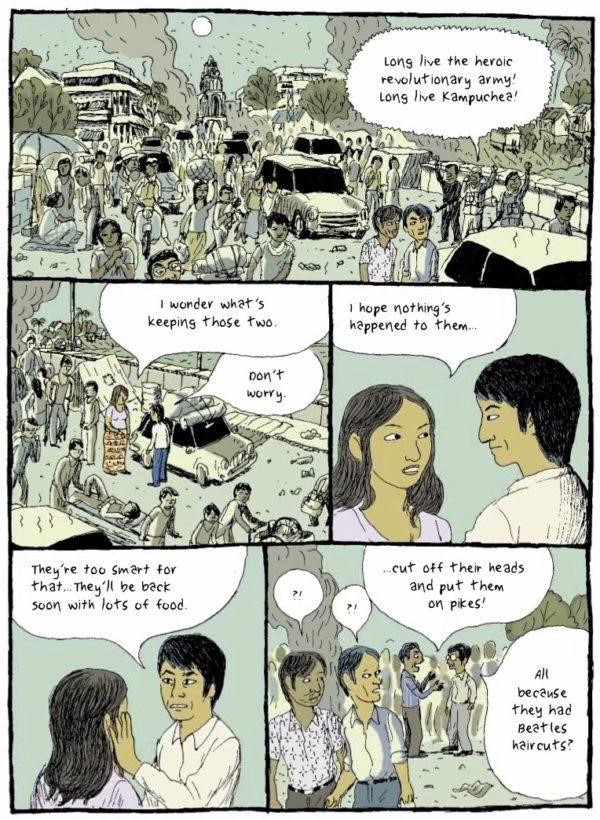

Veasna, who now makes his home in France, was born just three days after the fall of Phnom Penh, the capital city of his nation of origin, Cambodia, and while the loss of over 2 million people at the hands of Pol Pot’s notorious Khmer Rouge regime between 1975 and 1979 is well known, their frankly bizarre ideology is less discussed in this day and age, to the point that seeing it play out on the page is a downright surreal experience. Veasna’s father, a doctor, was as good of a case study of this in action as one could ask for: the so-called “intelligentsia” were frowned upon under the philosophy of Angkara, a peasant farmer movement that favored folk medicine and began shutting down not just institutions of higher learning, but cities in general, as part of their sub-utopian plan to transform the renamed country of Kampuchea into some kind of massive agrarian collective. As their grip on power tightened, the absolutism of their outlook went from idea to action with devastating results.

To that end, families were split up, with kids being indoctrinated/”re-educated” into the Angkar way of thinking while their parents were worked to the bone on state-controlled farms/labor camps for a ration of one disgusting-looking (and tasting, I’m sure) bowl of rice gruel per day while the elderly, ostensibly venerated by the new regime, were given two. It was really the children, though, who were the Khmer Rouge’s focus, trained as they were to become the eyes, ears, and snitches of the state. It’s easy enough to think that we’re above such nonsense here, of course, but anybody taking comfort in that pipe dream never went through the “D.A.R.E.” program in American high schools, where uniformed cops came into classrooms and told kids to snitch on mom and dad for smoking pot. I reiterate — under present circumstances, Veasna’s book is very much a cautionary tale.

Year of the Rabbit can also, in absolute fairness, be a bit of a confusing story. Historical fealty is important here, even crucial, but the sheer scope of the slaughter that went on is so staggering that it can be tough to keep track of who was who when we start learning about characters we’ve met, largely in passing, ending up dead, or at least rumored to be so. This is perhaps inevitable in any story with a “central” cast of characters this large, but you do, tragically, need a scorecard to keep up once the mass death starts in earnest. It’s all as hopeless and as depressing as it sounds, but the atmosphere of ever-present danger makes this a reading experience that’s more intense and nerve-wracking than it is actively bleak — and, to Veasna’s credit as a storyteller, this in no way cheapens or minimizes the tragedy he’s recounting, but rather sharpens and personalizes it.

I’m somewhat less enamored with certain aspects of Veasna’s skills as an illustrator, although, when one considers the art in general, it’s still the case that there’s far more good than there is bad. His muted pastel color choices are pitch-perfect when it comes to setting the tone of vibrant lives slowly being drained of that very vibrancy, and I find his simple figure drawings both instantly appealing and communicative. Yet, he struggles to convey spatiality in a number of his panels — particularly as far as depth goes when characters are in close proximity to each other — and while this lends the proceedings a certain air of immediacy by placing almost everyone and everything in or very near the foreground, it’s an accidental immediacy that isn’t even necessary given the gripping nature of the narrative itself. Honestly, though, it’s such an accomplished work on the whole that I feel like a little bit of a jerk for even bringing this quibble up, but nevertheless, it’s not only a recurring issue, it’s one that’s pretty damn hard to miss.

Still, Veasna makes up for this small flaw with some really innovative little touches that add power and personality to the project such as the introductory pages for each chapter showing some sort of illustrated “artifact” of the times, whether it’s a map of the country’s shifting geography or a handy visual guide on how to appear suspicious to the Khmer Rouge. Likewise, his uniquely “decentralized” approach to plotting really pays off toward the end, when events begin moving at breakneck speed. You come to realize both how meticulously constructed this whole story has been from the outset, and that there’s still a place, even during a historical epoch this seemingly unforgiving, for hope — as evidenced, of course, by the very fact that Veasna himself is even here to author this work. That reality alone provides positive closure to all of his family’s sacrifices and struggles, and he honors them — as well as those lost along the way — with this deeply harrowing, deeply human, and deeply important recounting of the story of their lives.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply