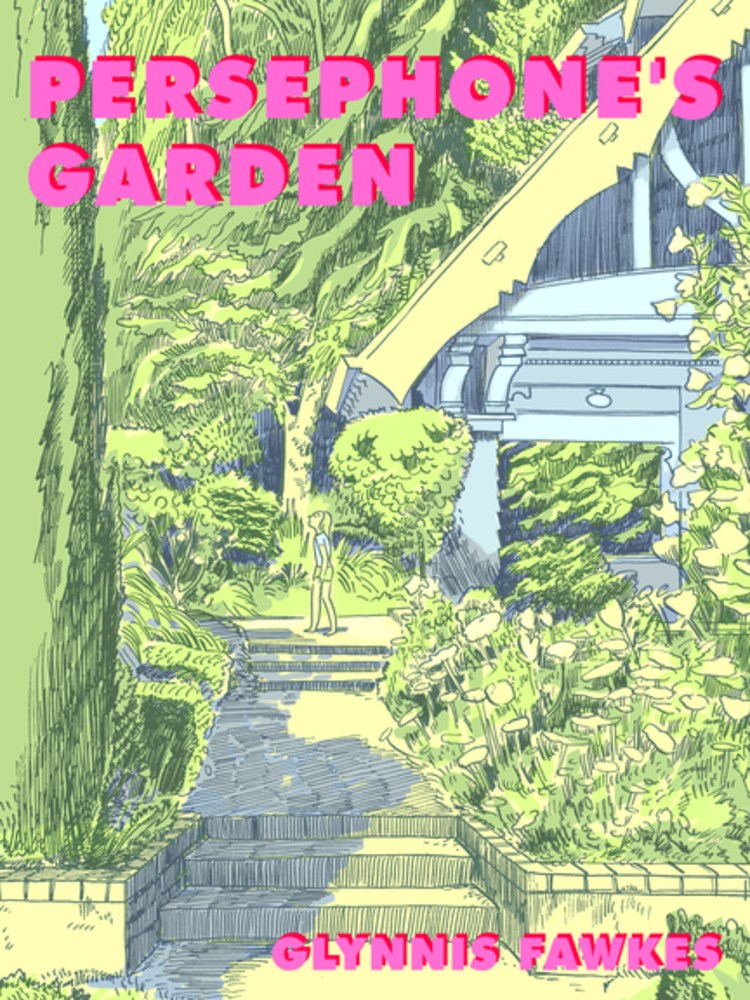

The cycles of life – of growth, flourishing, decline, and death – are the root of memoir and memoir comics. Glynnis Fawkes’ latest collection, Persephone’s Garden, makes that connection obvious through the titular reference to Greek mythology. Persephone is the goddess of vegetation kidnapped by Hades to be his bride in the underworld. She is the daughter of Demeter, the goddess of agriculture; when the two are united, the world blooms, and when the two are apart while Persephone is forced to stay in the underworld, the earth lies barren. It’s an apt metaphor for the seasons of life, but it’s also a nod to Fawkes’ career as an archeological illustrator and as a world traveler, the tales of which comprise a majority of this book.

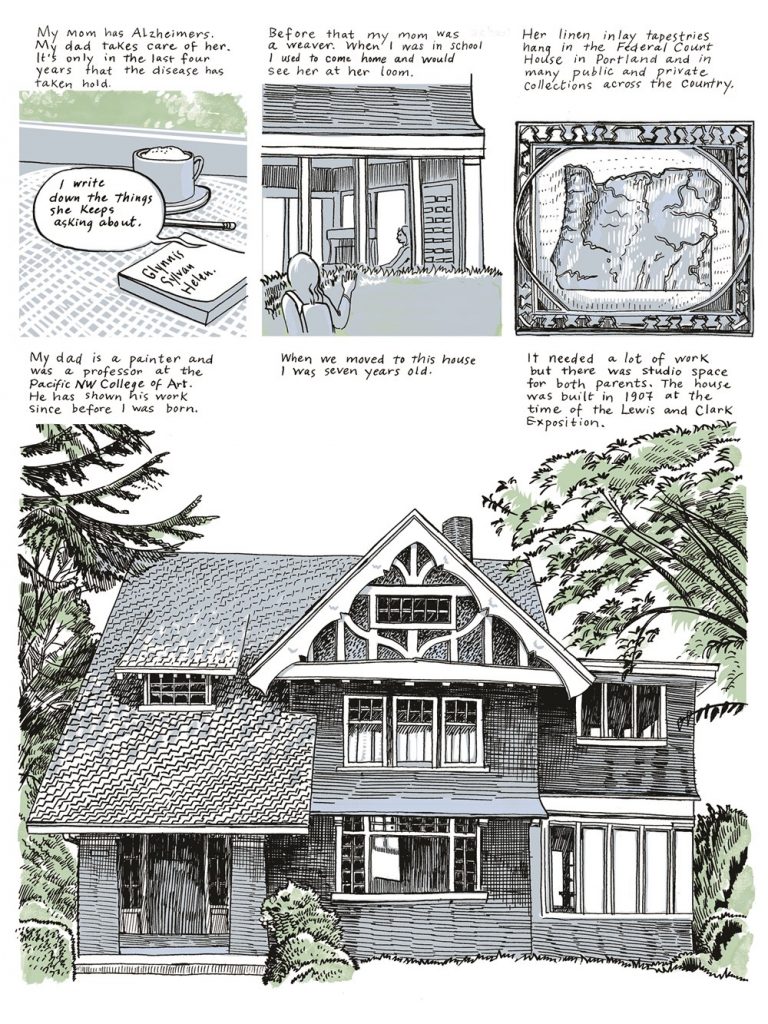

In that sense, you could say that the majority of the focus of Persephone’s Garden is on the growth of children and the flourishing of a life; Fawkes introduces us to her work and then starts the collection with “Troia,” an homage to Richard McGuire’s Here. Only a few pages long, “Troia” shows an excavation site where Fawkes is working, showing it as it probably existed as a part of the epic poem Illiad, all while she makes corrections to illustrations, eats snacks, and toils away in an open-air tent. The story, while short, gives us an idea of Fawkes’ range as a cartoonist. The pages are gorgeously detailed, a testament to her skill as a draftsperson. Her color selection is likewise brilliant, and I feel myself being pulled into these places. Her drawings in “Troia” seem far more real to me than anything knocked out in something like Carnet de Voyage, and they give the reader the opportunity to sense the space she inhabits as she tells her stories. These comics are drawn tightly, with a nib or fine-tipped pen, and so they have a precision that I find intensely appealing.

That preciseness is often eschewed in the middle of Persephone’s Garden as Fawkes draws a large portion of the book with either a brush or a brush pen, using a more hastily constructed four-panel grid that captures the lives of her quick-witted and quick-tongued children. She also uses this four-panel grid to detail her life on an archeological dig site. The grid isn’t completely essential, and Fawkes often modifies it to draw horizons and scenic shots, but that square composition makes the comics quick to read and flip through. These comics are loose; Fawkes is trying to capture something essential. The moments she captures are little things, memories that would be grayed out and forgotten over time.

The reason for this desire to capture small moments becomes obvious early in Persephone’s Garden. Fawkes’ mother, a once talented textiles artist and weaver, now suffers from Alzheimer’s and has forgotten her art and her family. Like the metaphor of Persephone, she is lost in the haze of the underworld, in a decline that can only move in one direction. Capturing the small moments of her children’s lives and her place in them, then, acts in three specific ways: as an act of resistance against her mother’s disease, which she may one day inherit; as a method of capturing memories by her own hand; and, perhaps, most importantly, as a therapeutic activity, a ritual that beats back the creeping shadows.

If Persephone’s Garden suffers from anything, it is that, when taken in part or in small doses, these goals are admirable and even laudable. There’s something compelling about the idea of making a collected work of art to fight the idea of a disease that takes art and memory from us. But when taken in whole, the scenes where her kids “say the darndest things” start to grate on the nerves. Fawkes captures these moments because she thinks they’re amusing, or because they will make good stories to laugh about when her children are grown. But perhaps because these stories lack a variety of tone, much of this writing would make you believe that Fawkes’ children are brats. Clearly the truth is a little more complex, as she’s depicted her children in many different ways in comics like Reign of Crumbs, but you wouldn’t know it from some of these comics.

Much of the rest of the book tells the story of her adventures as an archeological illustrator in Greece, or abroad in places like Cypress, Isreal, and Turkey. Her experiences in these places, with or without her kids in tow are often gorgeously rendered, and most of all make me wish to update my passport and get on a plane.

And that is the paradox of Persephone’s Garden; it is immersive and gorgeous, often funny, clearly made with a purpose. That purpose strikes home for me and makes me think about my future and the records I make of my life. But sometimes the results of that purpose make the work hard to stomach. Perhaps it is just the balance of the works in the book or the ratio of the comics that comprised the book. Would the book have read better if the middle section was broken up more with longer pieces, or trimmed for length? I think so, but I’m not sure. Who can say?

Ultimately I’m of mixed opinions when it comes to Persephone’s Garden. The book is lovely, but it’s hard to feel the core essence of the cycle of life that Fawkes is considering when a large section of the book is watching her children complain. Life is not simple, and moments like the ones Fawkes captures are ephemeral. Capturing them was likely essential for the artist. But choosing what to include in Persephone’s Garden is where I think the collection flounders. I think a leaner profile and a more curatorial eye would have suited the collection better. I loved much of Persephone’s Garden, and I will continue to actively seek out Fawkes’ work. Her illustration is beautiful, her colors well considered. Her stories of times abroad are effective and alluring. But Persephone’s Garden is an uneven work, heavy with moments that were captured with purpose, that ultimately work against the progression of the book.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply