The popular notion of manga in the United States is that it’s a subgenre of comics. Manga gets its own section at the library, gets its own shelves at the bookstore, and, as the saying goes, has its own set of adherents. The truth is that manga, alongside the collective output of Scholastic Books, is comics, at least when you consider things from a market and sales perspective. In 2017, Viz Media was 23% of the total US graphic novel market, selling numbers that would make corporate comics green with envy. Because of the high volume of sales and continued growth of the manga market, there’s been an explosion in the variety of available titles to English-language readers. Rather than thinking about Japanese comics as a subgenre, it probably makes more sense to think about them like the comics of other nations.

And, just like European comics come in a variety of genres and styles, so do the comics from Japan — and one of the most controversial and derided is the genre of Boys Love (sometimes referred to as yaoi or BL in the United States). Boys Love comics are a romance subgenre of gay male relationships written from a female gaze and consumed by female readers. The vast majority of these books are written by women. In a country that is more socially conservative than the United States, these books are often looked down on, and their readers call themselves fujoshi (a word that is literally translated as “rotten girl”), a reclaimed insult from the early 2000s.

Publishers like the mostly-defunct DMP popularized the Boys Love subgenre in the United States, and now publishers like Viz Manga (through its SuBLime imprint) are the major touch-point for most fans. Like American romance novels, these comics can range from chaste to explicitly pornographic, although most of them fall in the middle somewhere with various shades of intensity. Manga publisher Seven Seas has recently dipped its toes in the water with a handful of series, including Our Dining Table and the classic The Cornered Mouse Dreams of Cheese, and has recently published a comic that is about Boys Love, but not Boys Love at all – BL Metamorphosis by Kaori Tsurutani.

I give you all the backstory about manga because it’s the bedrock on which BL Metamorphosis is built — the comic isn’t Boys Love, but it’s about two women of vastly different ages who come to build a meaningful personal connection through the medium of Boys Love comics.

The two women in question are Yuki Inoichi, a septuagenarian widow who teaches calligraphy in her home, and Urara Sayama, a teenage bookstore clerk and high school girl who happens to be into BL comics. When Ichinoi walks into a bookstore to cool off from the summer heat and inadvertently purchases a BL comic, Urara takes an interest. When the elder woman decides to not get it wrapped in paper (something done in Japan to shield the work from prying eyes, a practice often used for BL manga) Urara is stunned — who is this elderly lady who is so brazen with her purchases? This small moment expands into something larger over time, and out of this chance encounter, an unlikely friendship blossoms.

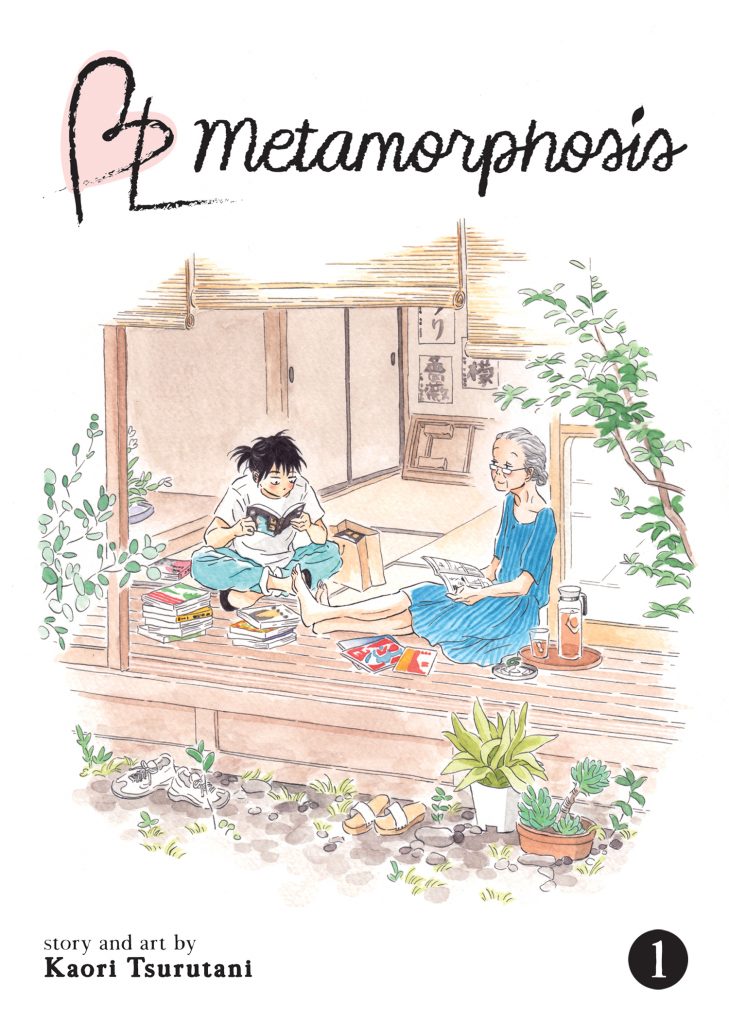

Throughout the book, Tsurutani’s art is both sturdy and complementary to the main themes. Her line is thin and delicate, and initially, her characters sometimes feel a bit wispy. Likewise, her figure drawing is competent but not exciting. For the first few pages, I was ready to be disappointed. But BL Metamorphosis flowers in the middle and comes alive during the last third of the collection. For every panel that looks a little under-cooked at the beginning of the book, there are twice as many detailed scenes of domestic Japan, full of house plants, stepping stones, crumpled sheets, and boxes of books. Tsurutani lavashes detail on the most unlikely places — the bookstore where Urara works, a cafe where they meet, a bridge where they exchange contact information. Unlike a lot of comics I’ve recently read, BL Metamorphosis makes me feel like it happens in a specific place rather than a generic city-space drawn with computers. These moments make the Japan of Tsurutani’s comics come alive, and the result is a gentle reminder of the human center of the work.

The human center of BL Metamorphosis is the relationship between Urara and Ichinoi. There’s a lot to unpack in the way these two women interact, and little details of these interactions show Tsurutani’s keen eye for detail. Tsurutani is quick to show us the formalness and stiffness of the way that Ichinoi and Urara interact early in the book through her drawing. Later in the book, the two characters become more relaxed around each other. Stiff bows and downward glances are slowly replaced by more casual pleasantries and less formal language. Little details like this drive both the visual storytelling and the strength of the narrative.

BL Metamorphosis is partly a tale of growing up and partly a tale of growing old. Tsurutani asks the reader: What are the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves? This is very true for the youngest of the pair, Urara, who hides her interests because she is ashamed of them (or rather, believes that others would shame her for them). The strength of BL Metamorphosis is that you never have to hear these thoughts said out-loud — Urara feels them, and you can see those thoughts in motion throughout the comic. Every time she hides her eyes or cringes, Urara is acting out her self-image. You even see it in the way that Tsurutani draws Urara — frazzled and unkempt, her hair sticking out in odd places. But in Ichinoi, a woman more composed and much older than her, she sees a different kind of future — a future where she can be who she is without shame or remorse. We see Ichinoi’s impact on Urara late in the book when she decides to change out of a frumpy black t-shirt into a cute sweater for the BL manga convention — something that seems improbable even 100 pages earlier. In Ichinoi, Urara sees a future that is tantalizing and reachable, and Urara slowly but surely steps out of her comfortable space and towards the image of that future, with Ichinoi by her side.

Ichinoi, by contrast, is settled into her self-image. But settling into something worn and comfortable means having a lifetime of regrets. There are things that she reminisces on, things that she would have done differently if she had a second chance. With Urara by her side, she has the ability to take a second shot at the opportunities she missed the first time around. We see her taking chances she might not have otherwise taken, and she leans on Urara as her guide through a new set of experiences. It is this spirit of change, of transformation, that drives BL Metamorphosis. Both characters are learning to be something new, something different, something better than they were before.

This process of learning and transformation is key to the tone of BL Metamorphosis and, perhaps, part of the reason it is one of my favorite books from 2020. Both of the main characters have asked, “What do I have to lose?” and have reacted accordingly. What strikes me about this book is the way that it emphasizes the potential of humans to change, no matter their age. Transformation is a potential for all people, not just the young. Importantly, BL Metamorphosis shows one of the ways that people change — not in a flash, but through disorientation, reflection, and chance-taking. If the title of the comic implies a sort of comprehensive change, then we haven’t seen one yet — because human beings rarely change in that way. But the seeds of that change are planted. The caterpillar has begun to prepare the space where it can transform into a butterfly. BL Metamorphosis is an earnest and heartfelt examination of intergenerational relationships, the deepening of self-conviction, and the development of community. In this first volume, Tsurutani has proven herself an adept storyteller and a fascinating new voice.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply