Disa Wallander seems like an artist plagued by the nagging sensation that she’s not real. Her comic strip Slowly dying and her collection from Peow! Studio, The Nature of Nature, dig into questions of the interior self and the process of art-making. Questions such as, “Who am I?” “What is art?” “What does this all mean?” form the crux of Disa Wallander’s debut full-length book Becoming Horses, published late last month by Drawn & Quarterly. In Becoming Horses, Wallander uses an expressive and sketchy cartooning style to dig into these existential questions in a wry and loving way.

There’s not much to the plot of Becoming Horses — rather, the book focuses on characters, featuring a cast of women artists, with attention paid to a specific three who travel across a wild and multicolored landscape in search of answers and horses. These women are part of a recurring cast from Wallander’s other work, and they travel alone and together as they move through space and interact with other characters.

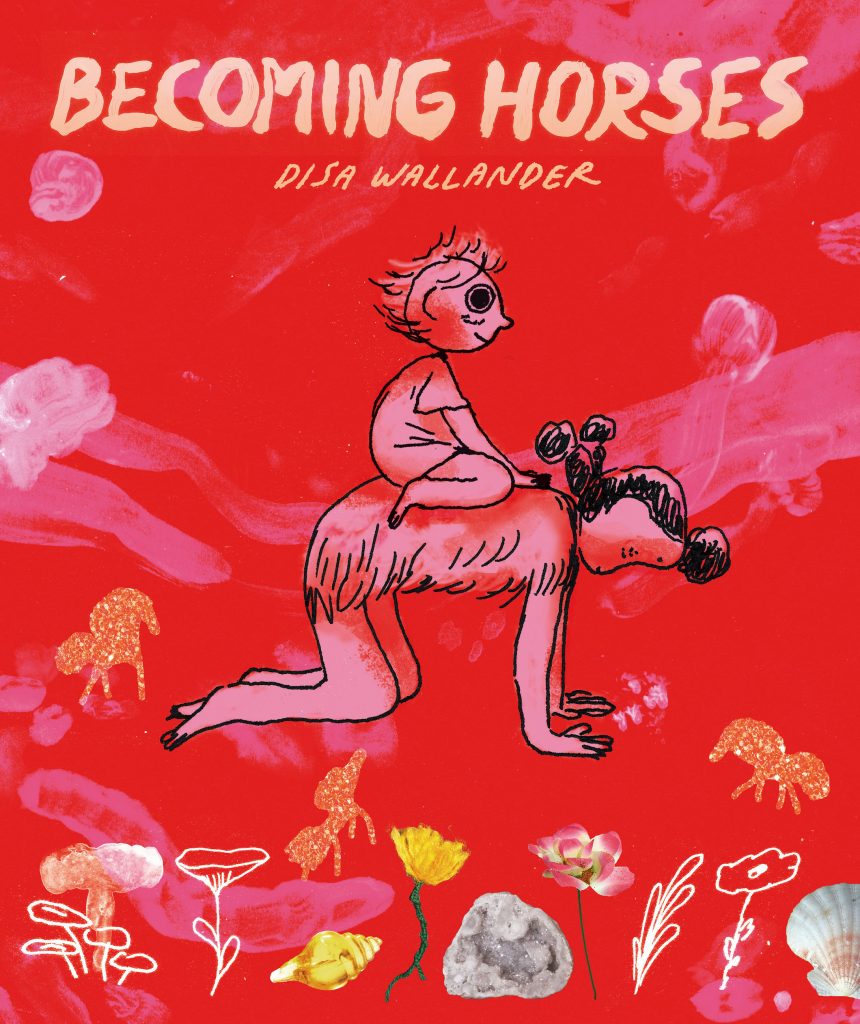

Saying that Wallander’s characters move through space is a fairly apt description of the comic since the cartooning of Becoming Horses is rather spare. Wallander has a kinetic and sketchy line, but the core strength of the work is in how her line makes her characters come alive. These illustrations are teeming with life, and Wallander is able to manipulate minor details of each figure to great effect; you can always tell when a character is upset or confused, despite the relative lack of detail. This preciseness is contrasted with the way that Wallander abandons traditional background illustration. Instead of vast plains, islands, or forests, Wallander abandons even the simplest line to represent the ground. Her characters float in the air, clearly existing in an undefined space, and they are often oblivious to what is around or behind them. Wallander’s alternative to the classic comic book background is something far more interesting and strange. Her characters, with their sketchy lines and simple airbrushed colors, rest on top of collages of paint, ceramics, and precious stones that Wallander has composed. These jewel-toned backgrounds have an innate wildness as if Wallander stumbled upon them and captured them. The truth is that this is a carefully and precisely generated chaos — Wallander composes each background to great effect. The interaction between her stark black line and the raucous collages behind them is part of the joy of the book. It makes each page a visual feast.

Despite its unique construction and Wallander’s choice to collage most of the backgrounds of the book, Becoming Horses feels more familiar than it feels new. Wallander’s work in Becoming Horses strikes a lot of notes that modern cartooning seems to have eschewed. In her spare and scribbly line, I see the work of Jules Feiffer. In her witty but melancholy characters, I see Charles Schulz. In her dry humor and vivacious cartooning, I see Tove Jannson. That puts Wallander in the company of masters, but Becoming Horses is far from a homage. Rather, it feels like Wallander has dug back into a style of cartooning that has largely been abandoned by her contemporaries. It’s a style of cartooning that embraces the unknown and is comfortable with ambiguity. There’s a simplicity of line that is juxtaposed with emotional complexity. It’s a cartooning style that lets readers fall into themselves. It’s a style that makes Becoming Horses both familiar and powerful.

Because of the spareness of the drawing in these vast collaged spaces, Becoming Horses often feels empty, even melancholic. Wallander breaks up the emotional space with dialogue that, at times, feels philosophical and other times whipsmart. As one of the main characters passes by, an artist notes that she has come to find peace and quiet so that she can focus on her work. Immediately, she confesses, “I haven’t made a single thing since I got here, but the suffering has been splendid.” This kind of dialogue is characteristic of the writing in the book, and it strikes a fine note between humor and despair. The writing has a silliness that belies its deeper philosophical meanderings.

Becoming Horses contains a rambling, philosophical ur-text that leads readers up to the edge of a proverbial existential cliff but never pushes them off. At the end of the book, a series of dark pages detail the essence of humanity. Disa Wallander observes that everything is constantly changing. “We live in a world of shiny moments,” she notes, and, in order to handle the strangeness of life, “You soothe yourself by eating the world whole.” This is as close as Wallander gets to a central idea of the book — that the world is a “world of looking” where the artist brings everything into themselves and then expels it all in a way that serves some personal goal, whether that is to be loved, or seen, or to express some indelible rage, joy, or sorrow.

But just as soon as she lays the framework for this philosophical thesis, Wallander quickly snaps it back with a bit of droll text or a depreciating joke. “Ha! Can you believe I just said that?” she seems to say. While these moments are clever, they make the entire work feel guarded, as though Wallander is afraid of what might happen were she to be completely earnest. Moreover, Wallander isn’t interested in giving anyone pat answers — she’s more interested in the journey to find the questions to ask.

While Wallander’s central point seems clear, her consistent undercutting of that point makes reading Becoming Horses disorienting, leaving the reader lonely on their journey to find the essence of the book. Becoming Horses guards its pearl of world-weary wisdom like a clam, with a tight jaw and a hard shell. But this is the essential reason why Becoming Horses is a successful comic. In any other context, that pearl could be a weight too heavy to carry. Instead, Wallander scoffs at herself and, in that gentle disdain, questions the conclusions she has come to. Becoming Horses isn’t about finding answers, just as it’s not actually about becoming horses — it’s a metaphorical journey of the human spirit, that, much like real life, has very few absolutes.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply