In his afterword to Moonshadow1, artist Jon J Muth writes about working on this comic in 1985, the period of Watchmen and Dark Knight Returns, and how he and writer J.M. DeMatteis set out to do something completely different. They have succeeded.

Moonshadow, originally serialized across 12 issues in the late-lamented Epic Comics line (with a finishing graphic novel published years later via Vertigo), is presented on the covers of most chapters as a “Fable for adults.” This is the style, the vibe, it is going for. On its face, it is a science fiction saga filled with visits to alien planets and featuring protagonists with a non-human (or, at least, non-Earth-based) perspective. But DeMatteis and Muth are not aiming for verisimilitude here; there is no attempt to explain the ‘how’ of the technologies involved or to develop alien societies that stand up to rational scrutiny. Things happen because they need to take the character through the journey, and the journey is more about the emotional aspect than the intellectual one. All well and good.

The thing about fables… is that they are short. They are, usually, stories meant to illustrate a point. Moonshadow is not short. There are over 460 story pages here, not including all sorts of extra material2. That’s not a fable size. That’s From Hell size. That’s Jimmy Corrigan size. That’s Alec size. The cutest fable would probably grind the kindest reader down at this size.

Still, not necessarily a problem: a good book can never be too long. Moonshadow certainly aims to be as grand as the comics mentioned above, or like the books it likes to quote. You know someone is aiming high when they start every chapter with a Tolstoy3 or a Beckett4. Like all these texts, Moonshadow is not short on ambitions. The creators are trying to talk about religion, organized and personal, about the place of books in the human spirit, about the cost of war, about forgiveness, about love, about sex, about war. Their canvas is the universe and the human spirit all at once. And for that, I salute them.

In many ways, Moonshadow feels like an ancestor of today’s creator-owned mainstream works, the kind of stuff pumped up by Image or Boom Studios or Aftershock or a dozen other publishers that seemingly melt into each other in your local Previews catalogue. Still, in one important way, it is very different: it doesn’t have the stench of the failed movie pitch to it. Moonshadow doesn’t read like someone wrote or drew this thinking of TV syndication, or an action-figure line. Moonshadow is complete and of itself. Idiosyncratic to the extreme. A reminder of days that were not ‘better’ but were, at least, slightly more naïve – the kind of personal works published by Epic, or the pre-Vertigo DC comics, weren’t all great works of art. But they made you believe they wanted to be great works of art. It’s good to reach out to the stars.

Alas, Moonshadow falls short of its ambitions. Quite short.

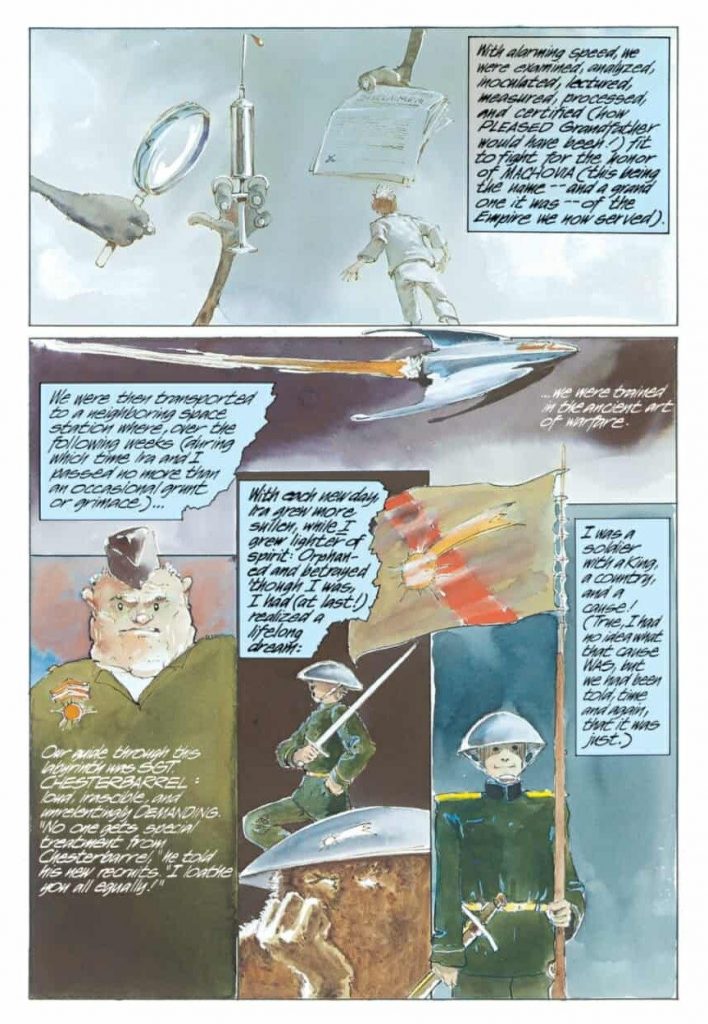

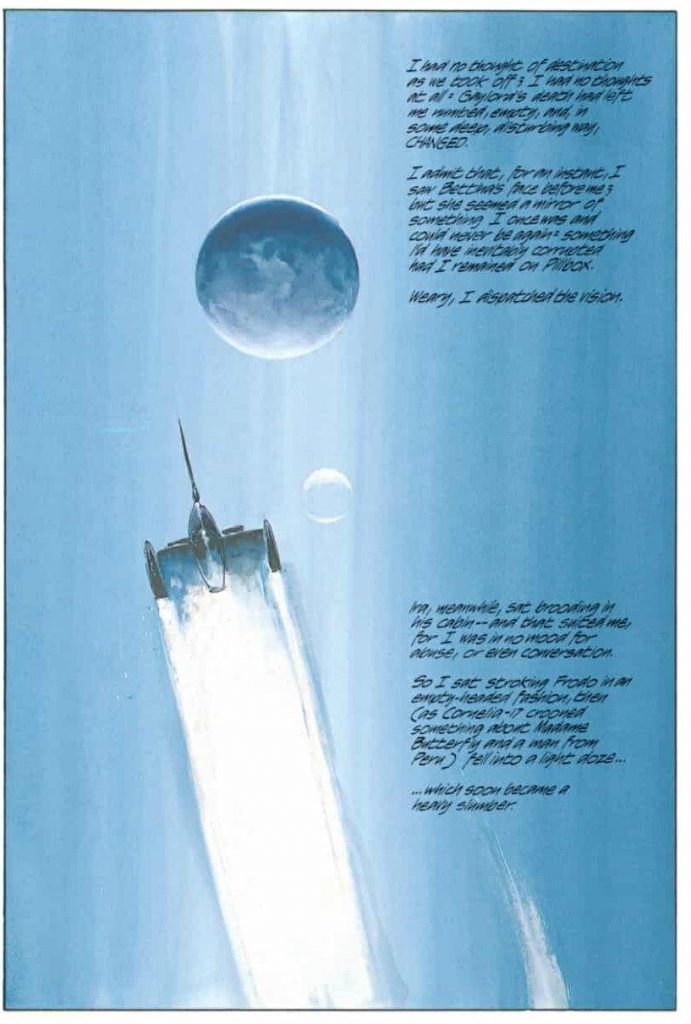

The story, slight as it is, involves the titular child – born of a copulation between a human woman, a Jewish hippy growing up during the 1960s, and a god-like alien being. After spending years growing up in a sort of an alien zoo, kept alongside other aliens by the same god-like entities, Moonshadow is suddenly thrust out into a hostile universe in a spaceship. Stuck with him is a grumbling partner-sidekick-mentor Ira, who cares little for philosophy but a lot for pleasures of the flesh, and a beloved pet cat Frodo5. They travel through several planets. Despite the vastness of the book, they only visit a few locations and seem to meet the same beings over and over again6. The aliens they encounter seem to embody less full characters and more like abstractions of philosophical notions and… wait a minute… a ‘fable for adults’… a child protagonist… a travel across a vast universe that is actually rather small… it’s The Little Prince. I hate The Little Prince. And I hate Moonshadow as well.

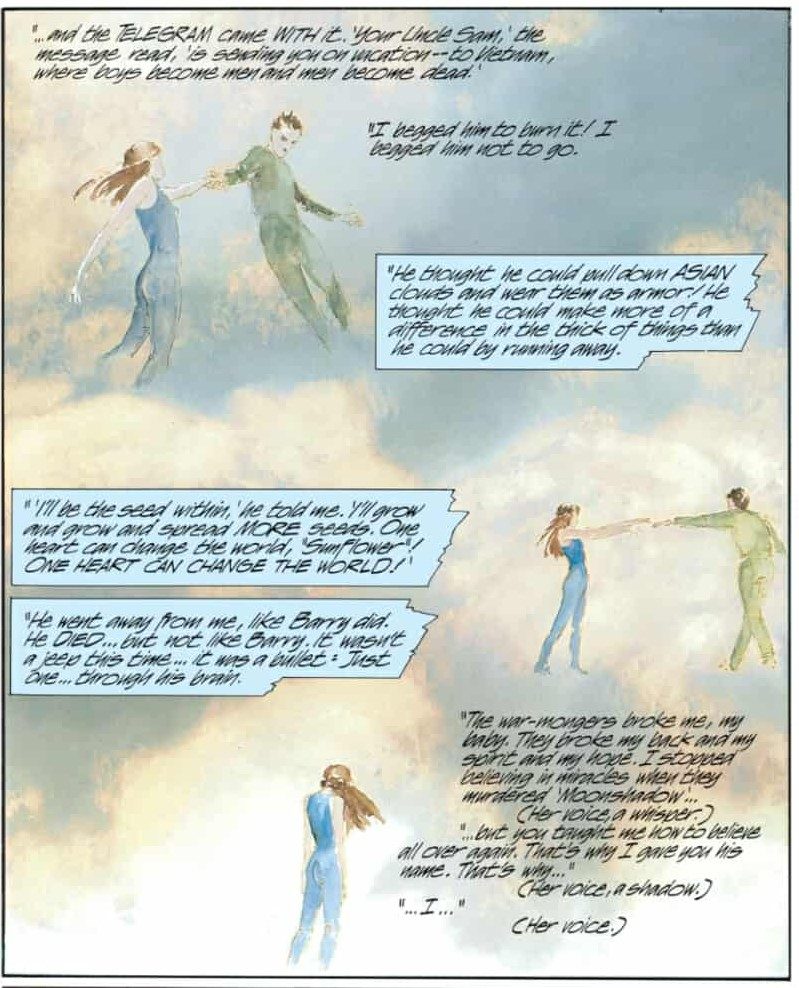

The character, not the book. The book I merely dislike. It’s perfectly possible to do a good work starring a loathsome character, the career of Vladimir Nabokov is a living proof, but the authors probably need to dislike the characters themselves, at least for a bit. I don’t get the sense that DeMatteis and Muth realize how annoying Moonshadow is. There’s a word in Hebrew called מתחנחן (mit-han-chen), which is hard to translate into English. Think of it as ‘coy’ with a sing-song edge to it. A sort of softness that seems to openly invite sympathy to such a degree that one starts to hate instead7. The character has this sort of quality to it – he is meant to be an observer and experience the universe for the first time, to explore the difference between the world as it appears in works of fiction to how things really are. Instead, he overwhelms. The book is drowning in prose; we hardly find a silent panel, never mind a silent page (when they do appear, they are as blessed a relief as water in the desert).

Most of that prose is in the form of long caption boxes, and one gets the feeling that DeMatteis thinks more in terms of an illustrated novel than a comic book. To make this work, over four hundred pages, you would need to be a first-rate prose writer. DeMatteis, per his efforts here, is not that writer. Consider his take on carnal knowledge: “Sex, like death, was the unknown, and no amount of solitary practice – however often, however eager! – could prepare me for the final plunge.” Or on the tragedy of war: “and he died: not dramatically, on some foreign battlefield, but in a horribly mundane fashion on secure American soil.” A sentence that appears clever but offers very little. You would not be surprised that Moonshadow tells us that war-is-bad, that organized religion is the opium of the masses, that tragedy is part of life and must be accepted, that sex can be fun. These are not insights of particular uniqueness.

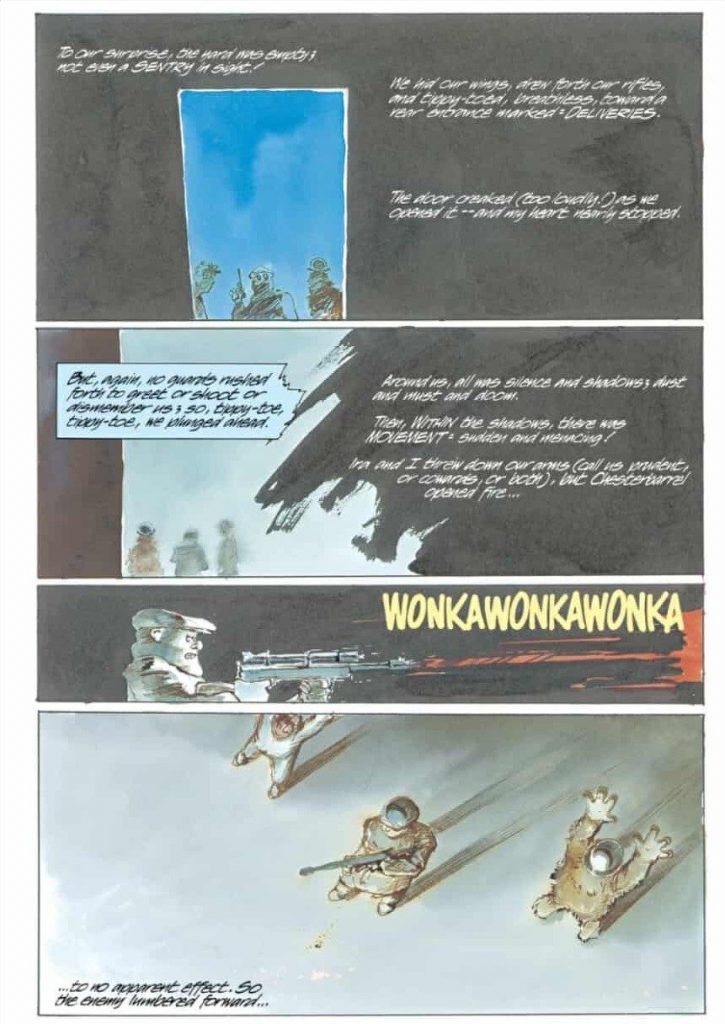

Since Moonshadow loves quoting, I can’t help but compare its timid take on a war, a ridiculous affair that exists with no relation to any material circumstances (this is a fable, remember, world building is not simply ‘shaky’ it is ‘nonexistent’), that is solved by one particular nice guy who can do it with a push of a button. Where is the pain, the concrete, real physical pain, of (to pick on a writer Moonshadow quotes) Tolstoy’s Sevastopol Sketches? There’s much ridicule in Tolstoy’s short stories, but the ridicule stands out because it is contrasted with the deadly earnest reality. The war in Moonshaodw is nothing; it bears scant resemblance to any real war, it is so symbolic, so parodic. It’s not War and Peace, it’s not The Good Soldier Švejk. These works got into your bones. Even The Butter Battle Book felt truer to life, and is one hundredth the size of Moonshadow.

Is the Moonshadow wholly without merit, though? No.

It has Jon J. Muth art (with occasional help by the equally talented Kent Williams and George Pratt), so, when the text stops trying to overwhelm the page, you get to look at some truly stunning imagery; any scene in which Muth goes to a more cartoony edge, flying close to comedy, is a stand out and gives a hint of a book that is less subdued and sad (and thus much better). As mentioned above, you cannot ding Moonshadow for lack of effort. It heaves and hoes and gives it 110%. The book certainly believes it is Atlas, carrying the weight of the world on its shoulders. It is not, but it believes it – and for some moments it almost convinces you.

Almost.

The period of Moonshadow’s original publication, the middle of the 1980s, was a period in which mainstream American comics stopped being afraid to dream big. New publishers, new titles, new initiatives, new independence for people to do as they please. Like the New Hollywood movement of a decade before, it is easy to look back on that period with unencumbered nostalgia, remembering only the titles that succeeded, the works that stood the test of time. Moonshadow is as emblematic of that period as any work you can choose to name. That doesn’t necessarily make it good. The Gates of Heaven is as emblematic of the New Hollywood period as The Conversation. Both are worth remembering, but not for the same reasons.

Muth and DeMatteis dreamed to do a work unlike Watchmen and Dark Knight Returns. Those two works are also high on ambitions, but they achieve those ambitions; faulty though they are – Watchmen and Dark Knight Returns are great works.

Moonshadow can only dream of greatness.

- Sorry, that’s Moonshadow The Definitive Edition – Expanded. Should one even expand on something that is ‘definitive?’ Seems like contradiction in terms. ↩︎

- Kudos to Dark Horse – it is and handsome package, and surprisingly cheap for its size. ↩︎

- Though Joe Queenan once suggested great authors should strike back at this trend by using “quotations from world-class hacks.” I guess the closest was The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao starting with a Stan Lee quote. ↩︎

- My inner English Lit BA rises in anger at these quotes – not so much that sources are bad, but that they are obvious. The literary version of saying Hitchcock is your favorite director. Fine by itself, but problematic in a work that constantly tries to impress the reader with its literary credentials. It certainly doesn’t help that the characters seem to misunderstand these texts: Moonshadow talks about the Fellowship going “off to find the ring of power” – when Lord of the Rings opens with the ring already in their possession; their quest is to destroy it, not to find it. ↩︎

- The cat is mostly there in theory, and seems to drift in and out of the narrative in random intervals. Less in ‘is there something fantastic about him’ manner and more in a ‘It sure looks like the authors forgot about him for a couple of issues’ manner. ↩︎

- The universe here is even smaller than in Star Wars – in which every two people who share a planet are bound to meet. ↩︎

- Quote Orson Welles: “I hate Woody Allen physically, I dislike that kind of man. I can hardly bear to talk to him. He has the Chaplin disease. That particular combination of arrogance and timidity sets my teeth on edge.” Arrogance and timidity, that’s Moonshadow (the character) in a nutshell. ↩︎

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply