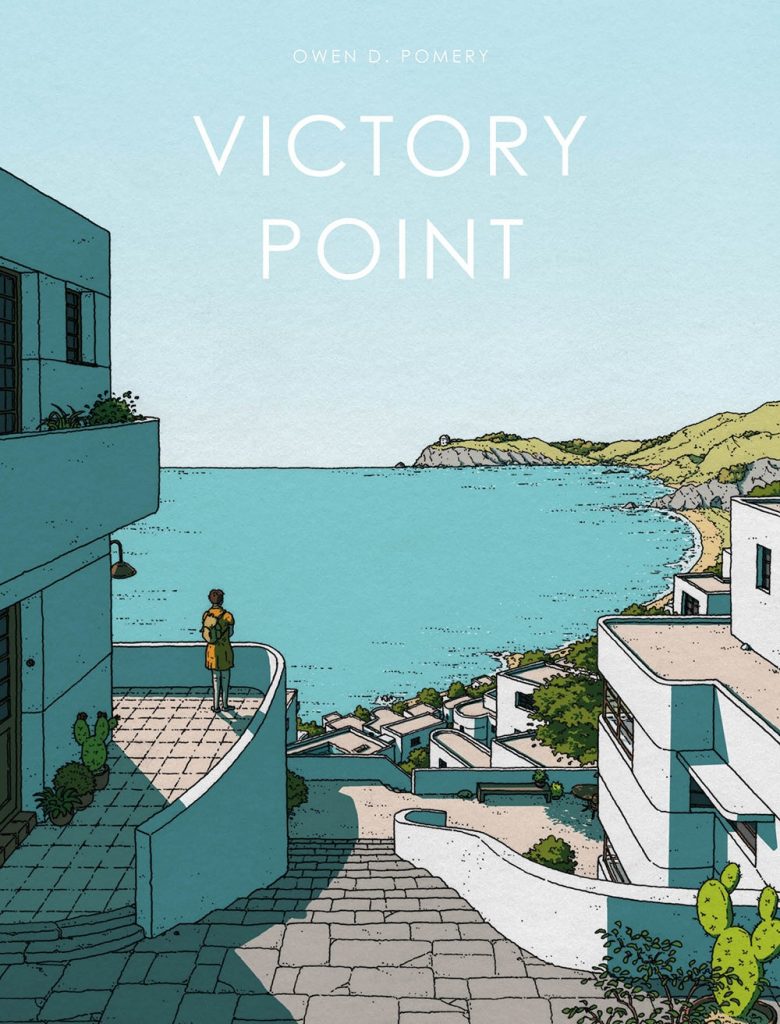

In mid-October, the folks at Avery Hill published VICTORY POINT, Owen Pomery’s latest graphic novel. The book follows Ellen, a young woman who returns to her hometown of Victory Point to visit her father. As Ellen sees the familiar sights and runs into people old and new, Pomery uses her experience to explore the idea of home.

Often, we have critics who want to review the same books as I do at SOLRAD, and most of the time, they are the ones who review the work. This time, however, I’ve managed to convince our lead critic and my colleague and friend Ryan Carey to sit down for a conversation about Victory Point, its strengths and weaknesses, and its overall effect.

Alex Hoffman (AH): Thanks Ryan for talking with me about Victory Point. I wanted to start with the concept that the book is built from – the idea that you can’t ever go home. Ellen is a bookseller in a large commercial store (a place like Barnes & Noble comes to mind) and is going back to her hometown, looking for something. What were your initial reactions to Victory Point and its main themes?

Ryan Carey (RC): I think that’s a fairly spot-on assessment, and, in that respect, it’s reminiscent of Hitchcock’s The Birds, Lynch’s Blue Velvet, and other works centered around a prodigal coming home for a visit and not necessarily fitting in with the local goings-on any longer. Pomery detours from the template a bit in that his fictitious locale is also something of a deliberate architectural curiosity that was designed at one point to be a kind of unique and self-sustaining community, which means it still attracts some “day tripper” tourism, but, other than that, it sort of fits into a fairly established storytelling tradition. If a reader is into narratives that evoke a strong sense of place, this certainly succeeds at that, and since doing so is Pomery’s explicit aim, it’s more than fair to critique it with an eye towards how successful he is at doing so. I will say that the one thing that gets under my skin is the tired “nobody who’s stuck around here has done much with their lives” stereotype, which strikes me as a bit rich coming from someone who is a low-wage retail worker themselves. It reeks of a kind of subtle elitism which posits that struggling to get by in a big city is inherently more noteworthy than doing the same in a small town. That slightly dismissive attitude toward the locals of Victory Point really does hamper the work, in my view.

Fortunately, this is a comic, not a novel or short story, and so Pomery is able to elicit a mood and feeling unique to his locale thanks to his superbly-detailed and lushly-colored clean-line art, which, to me, was the book’s strong point. He’s clearly considered every aspect of the town and his characters from an aesthetic point of view and his visual communication skills are top-notch. How did you feel about the book’s art?

AH: I love that you brought up that stereotype. It’s threaded throughout the book, and part of Ellen’s inability to reconnect with her previous schoolmates and peers is this sense of entitlement from moving away. There’s a kernel of truth in that interaction, but it is cloying in its simplicity.

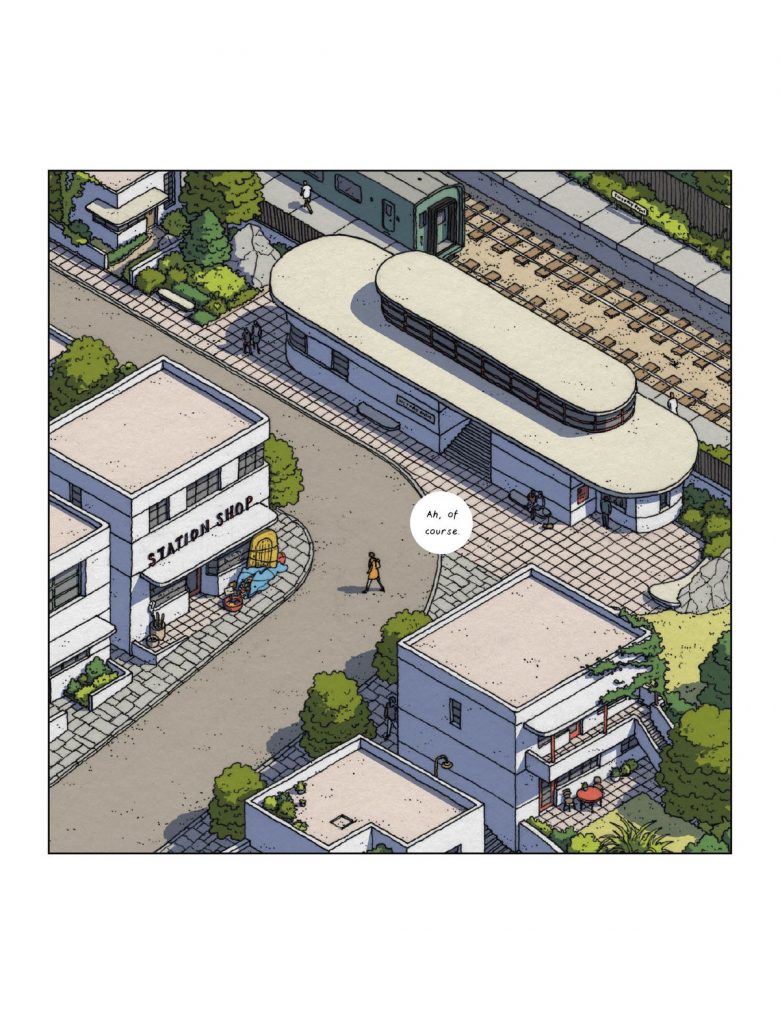

To get around to answering your question, I’m of mixed opinions when it comes to the art of Victory Point. Pomery’s page layouts are lovely, and I think the art shows off his skill as an architect. I love his pages where Ellen just sort of walks through town. It allows Pomery to draw in this pseudo-isometric style that fits his linework and allows him to go all out on these gorgeous vistas. There’s a series of pages at the beginning of the book, I think it’s pages 10-12, where Ellen is walking away from a flubbed conversation through town, and it’s a gorgeous series of pages. If nothing else, it shows that Pomery has an excellent mind for place, something I think most cartoonists would rather avoid. His series of pages where Ellen goes swimming in the sea are likewise breathtaking. The image of her looking out into the waves is a highlight of the book.

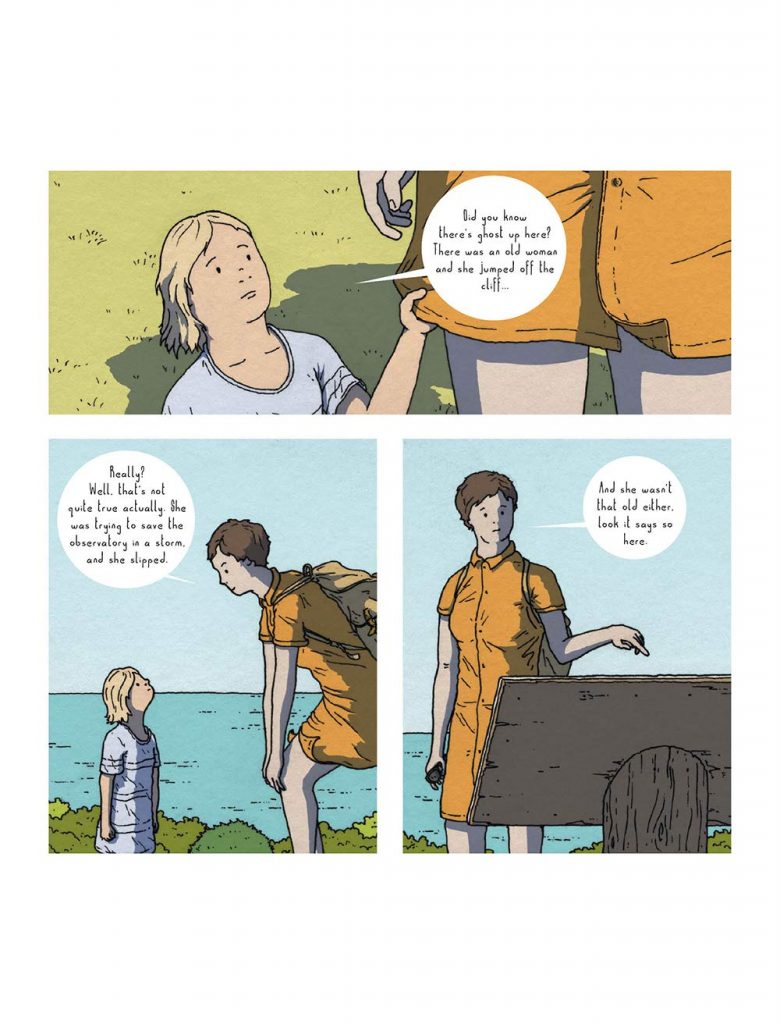

The actual people of his narratives I’m less impressed with. All of the humans in Victory Point are sort of blobby and amorphous, which would normally be just fine, but the contrast between the detailed vistas of Victory Point and the relatively nondescript people is noticeable enough to be distracting, which is the worst kind of experience in a story like this.

One of the things that I found interesting about the way Pomery sets up the story is by using these interstitial pages of text that give the background of the town of Victory Point. It’s an effect you don’t often see in comics, but I’m not certain how successful it is in this book. What did you think of that choice — good, bad, indifferent?

RC: I’ve seen shit like that before, so frequently that it doesn’t stand out, but I think that it is fundamentally lazy. It allows a cartoonist to dump a bunch of info onto a page and then give you six or eight pages of silent stuff. Which is what they really want to draw, so fair enough, but the far bigger challenge is to impart all that information either purely visually, or with an economy of dialogue that won’t break the fluidity of the visuals. That being said —

Fluidity is NOT necessarily a label I’d attach to Pomery’s visual storytelling in the first place. You mentioned his architectural background and it’s evident in his drawing style, which has its previously-discussed “pluses,” but on the minus side of the ledger, his art is stiff and stationary. He struggles with depicting movement in a naturalistic fashion, and his panels tend to feel more like a series of stand-alone drawings rather than a series of interconnected ones. This gives readers several occasions to pause and marvel at a particular panel — many of them in this book are certainly worthy of such attention — but there’s a noticeable absence of a smooth transitory feel from one to the next far too often here. In cinematic terms, it would be like having too many cuts both within scenes and between them and refusing to just let the camera roll once in a while. I mentioned Hitchcock and Lynch earlier, but if there’s one filmmaker I would compare Pomery’s aesthetic to above all it would be Kubrick, in that there is a clinical precision to all this that’s beautiful to look at, but occasionally lifeless and antiseptic.

That’s nothing, however, compared to the Pomery’s wooden dialogue, but I think I’ll let you pick up that baton and march with it —

AH: Absolutely. You and I are on the same page regarding Pomery’s stiffness, and it is by far my most major complaint about Victory Point. You mentioned the stiff and stationary art in detail, and I think you could say that all of the work in Victory Point is stiff. The dialogue struggles to keep the reader engaged with the work. If I had to say anything, it’s that there’s a sort of “posing” of characters in specific places, in a way similar to the Italian fumetti or Spanish fotonovela traditions. The word balloons are more like narration than they are like actual dialogue, which makes some of Victory Point a real slog to work through.

The scene where Ellen interacts with the little girl at the observatory is a prime example of this. Questions and statements happen in the same balloon, often different topics occupy the same balloon. Even if the dialogue sounded natural, it would feel like all of the characters were talking as quickly as possible to get everything out in one breath.

I think the issue here is the way that Pomery uses page layout. I would say that Victory Point is minimalist in this regard. Pomery likes the use of the side-by-side 2×1 gridded page or panoramic shots that give the reader the chance to see the environment, which plays to Pomery’s strengths as an illustrator. Very few pages have more than three panels, and that’s consistent throughout most of the book. But I think that if you are trying to keep everything contained in a slim page count like this one (I think Victory Point is something like 80 pages) and use page layouts like these, you are prevented from making a lot of breaks to disentangle conversation. This makes it hard to portray conversation in a way that is naturalistic, which ultimately seems like Pomery’s goal given the way the book is illustrated.

An important comparator that I think makes the point here is Paco Roca’s The House, published in 2019 by Fantagraphics. Roca has a similar penchant for panoramic shots, explores similar themes, and is a fan of detailed place drawing (although neither as precise nor as lovely as Pomery’s). Roca’s pages often have 6 or more panels. It doesn’t seem like a big difference, but having extra gutters and extra space to work means you get to put in those breaks in conversation that make it feel like actual talking.

RC: Yeah, those all strike me as fair points, as well as a valid comparison vis-a-vis Roca’s book. I don’t think I’m as generally “down” on this book as you are simply because I think Pomery does a very nice job of evoking a certain mood directly tied to a certain place, and I did find the backstory about Ellen’s mother intriguing if somewhat clumsily inserted.

That being said, the book doesn’t really succeed as anything other than an exercise in casually moody evocation, and that’s probably not enough to warrant a “read” or “buy” recommendation on my part unless that’s precisely what a prospective reader is looking for. Certainly, the ending was a convoluted mess. Ellen opens her own book shop some months after the Victory Point visit and, while the connection between her trip back home and her sudden leap from low-wage store clerk work to a full-fledged business owner is inferred, it is never directly explained. The frankly laconic pacing of the rest of the book (with which I didn’t have a huge problem on its own) doesn’t lend itself to a tidy “and the moral of this story is…” sort of ending, so why Pomery felt the need to grasp for one, but then not elaborate on it, is all a bit beyond me. Especially when said moral doesn’t make much coherent sense.

AH: I think you’re right about the way that Victory Point evokes a specific mood. Perhaps you could say that it invokes a sense of nostalgia. Pomery is trying to remind us of the fragility of life and the special nature of the places we grow and live. There’s a muted hopefulness to the book, and I get the sense that it’s ultimately a compassionate work. Pomery is close to something special here, but he never manages to actually grasp it.

I also agree with your point about the ending. Pomery is condensing the narrative of this comic in some odd places (often with those blocks of text I mentioned earlier) and makes the final presentation disjointed. The book is laconic; that’s one of its major strengths. It’s in a hurry to go nowhere, and I actually like that quite a bit. But the ending throws everything up in the air in a way that I don’t think is either earned or necessary.

RC: If he’d stuck to his core concept here of a person returning home for a visit and not necessarily tried to make it something quasi-profound, he may have succeeded in crafting a reasonably memorable, if not particularly substantial, mood piece. Instead, Pomery has tried to impose a larger meaning on every character, conversation, and interaction. Because of that, the final result is a project desperately in search of meaning, apparently finding it hard to come by, and certainly offering none. I’m not one of these critics who derives any sort of perverse sense of joy or satisfaction from slagging someone’s efforts, particularly when it comes to a project such as this that’s obviously done far more for love than it is for money, and I think we’ve both been fairly clear that there are strengths Pomery can build on moving forward from here, but as far as Victory Point itself goes, I found it a confused mess that wanted to be more than it was capable of being.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply