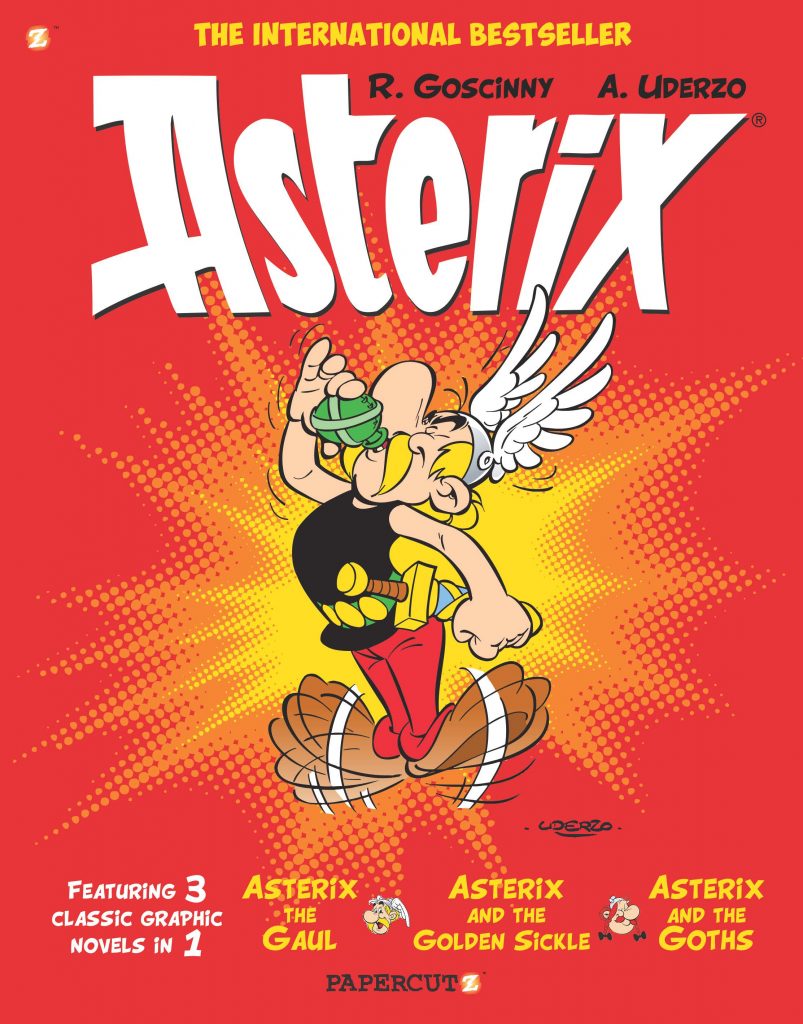

Like soccer, room-temperature drinking water, and universal health care, Asterix is popular everywhere except America. But with a slate of newly translated editions beginning this month, Papercutz is betting that France’s biggest cultural export will, at last, take these shores by storm.

Of course, even Stateside, true comics geeks are at least passingly familiar with the comic adventures of Asterix and his village of Gaulish holdouts on the fringe of Caesar’s Roman empire (British translations have been available here for years). But, before we go behind the scenes with the series’ new American translator, here’s the bare bones on the brawling bantamweight believer in Belenus.

First, the hype is real. Since the debut of Asterix as a serialized two-page bande dessinée (comic strip) in French magazine Pilote in 1959, it has gone on to sell 380 million copies of 38 collected volumes (a.k.a. albums) in 111 languages.

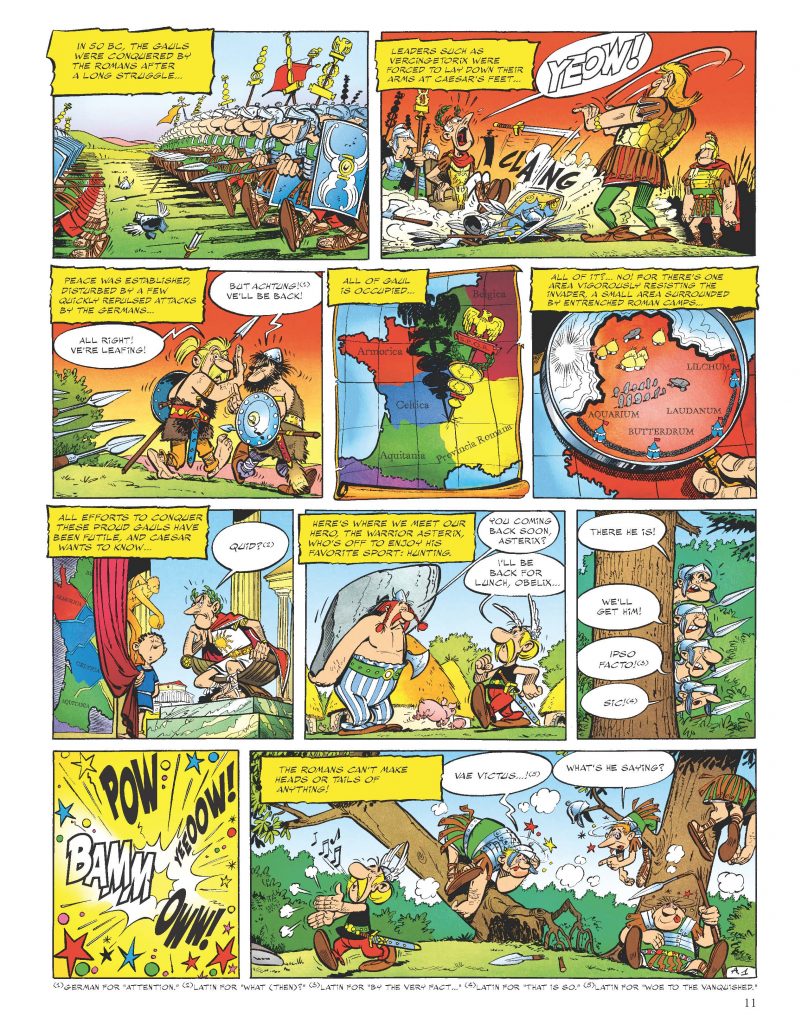

The titular star is a diminutive Gaulish warrior in 50 BC. Asterix’s coastal village is the only one in Gaul not yet conquered by the Romans, thanks to a magic potion brewed by the village druid that bestows invincibility for a limited time (the secret ingredients include mistletoe, strawberries, and lobster). But anyone can imbibe a potion; it’s Asterix, with his cunning and craftiness, who’s selected to protect the village, with help from his bulky sidekick, Obelix.

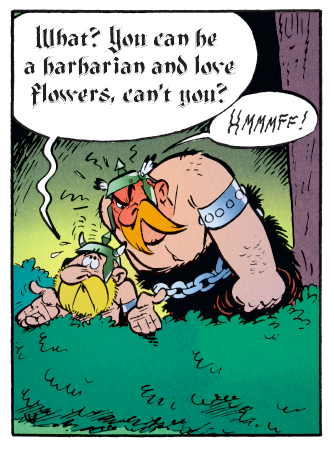

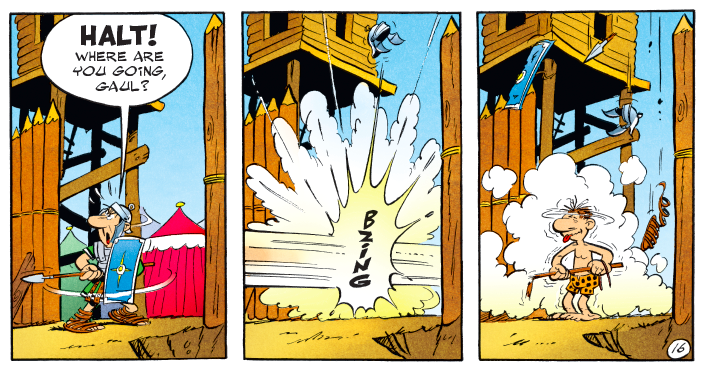

The series’ humor is itself an elixir mixed of several ingredients, including: the myriad and epic ways that our heroes find to thoroughly befuddle and drive batty the Romans and other adversaries; blatant anachronisms; flurries of puns; goofy names; and gentle pokes at national stereotypes—e.g., the Swiss love cheese and banks—and even regional stereotypes within France.

One explanation for these stories’ universal appeal? For a series hailed by Frenchmen as being as French as French bread, Asterix was a bit of a melting-pot creation.

Credit: Anne Goscinny

Asterix’s co-creators were René Goscinny, the writer (or “scenariste”), and illustrator Albert Uderzo. Goscinny was born in Paris to Polish Jewish immigrants, was raised largely in Argentina, and lived as a young man in New York City, where he befriended and worked with Harvey Kurtzman, founder of Mad magazine. Uderzo was born in France to Italian immigrants (even his two older siblings were born in Italy), and he was a huge fan of Walt Disney animation, Floyd Gottfredson’s Mickey Mouse strips, and other American cartoon work (Goscinny died in 1977; Uderzo died just this past March; the series has continued under Uderzo’s hand-picked successors, artist Didier Conrad and writer Jean-Yves Ferri).

Goscinny’s Jewish background, in particular, has spawned speculation that his tales of spunky Gauls thwarting an invading force could be read as a way of working out angst over the still vividly remembered Nazi occupation of France. The Jerusalem Post quotes a French expat in Israel who argues that the village druid in Asterix is a “rabbinical figure, complete with the long white beard, [whose] magic potion gives [his people] the strength they need—not to win, but to persevere, to resist assimilation and keep their traditions alive.”

Perhaps it’s no accident that, in addition to German, Spanish, and other languages, the books have been translated into Hebrew, Welsh, Breton, Cornish, Corsican, Irish and Scots Gaelic, and other minority tongues.

That being the case, why not editions aimed at the Yanks, using American idioms and cultural allusions? Papercutz’s first book in this line, collecting the first three stories/albums (“Asterix the Gaul,” “Asterix and the Golden Sickle,” and “Asterix and the Goths”), came out last week—the day after Bastille Day, as it happens.

Will Americans respond? That may depend on whether we see ourselves as the heirs to the scrappy colonials who took on a mighty empire and won, or as … well … an empire ourselves; whether we root for the underdog or blame the underdog for his lowly state.

Or maybe we’ll respond because the stories are damn funny and delightfully drawn.

In any event, the British translations by Anthea Bell with Derek Hockridge are critically acclaimed and rightly beloved by many (Bell’s the one who came up with character names like Cacofonix for the village bard and Vitalstatistix for the chieftain—most of these carried forward into the new Papercutz editions). But they haven’t made Asterix a force over here yet. Papercutz clearly believes it’s time to swap out the “I say”s and extraneous U’s, for fresh editions more apt to hook new generations of Americans.

Enter Joe Johnson. He’s a professor of world languages at Clayton State University outside Atlanta; he lived in Alsace, France for two years as an English lecturer; he’s chaired departments, published a monograph and scholarly articles, edited books, presented at conferences, and written reviews.

And he’s been translating French comic books into English, largely for Papercutz and sister press NBM, since 1997.

Professor Johnson spoke with me via Skype in early June, at which point he was already working on the eleventh Asterix volume, in addition to teaching summer classes.

The conversation has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity and length.

– – – – – – – –

Patrick Kennedy: You’ve done more than 240 translations. How do you fit these in, along with your teaching course-load?

Joe Johnson: It’s just one of the things I do professionally. For my university, these count for me as publications. You know how important that is, “publish or perish.” When I became a professor, I never knew that the major thing I’d end up doing would be translations.

PK: What drew you to French in the first place?

JJ: I was bookish as a kid, so French had a cultural appeal to me, from reading The Three Musketeers and stuff like that. My high school started offering French, it was a vibrant and enthusiastic teacher who taught it, I signed up, fell in love with it, and that’s what I went on to major in and do all my degrees in. I added Spanish and teach it too, but never attempted to translate Spanish professionally.

PK: Were you a fan of comics growing up? Any French comics in particular?

JJ: I was completely unaware of French comics as a kid. I was very much a fan of American comics. My favorite ones were, for DC, Legion of Superheroes and Justice League, and, for Marvel, X-Men.

PK: How would you describe Asterix to an American acquaintance who’s never heard of it?

JJ: I’d say it’s a comic book set in antiquity in France that, at the same time, has these characters who are kind of avatars for contemporary France. It’s a way to talk about what’s going on in modern France and Europe at the time the books were written. But they still have a story that’s fun and set in the past.

PK: How did you feel about being tapped to translate Asterix?

JJ: I have to say, I was hesitant, because I thought, “This is a big cultural touchstone for a lot of people. It’s got a life of its own, and I’m not gonna have the freedom with this that I do for other books.” Like, say, Dungeon, which is one I’m working on now, a Lewis Trodheim series—it’s a big, sprawling kind of joshing about Dungeons and Dragons, with a panoply of characters. I love working on it, but [it’s less well known] and I don’t expect heavy scrutiny. I suspect Asterix is gonna get a bit more scrutiny. Even the Smurfs—I’ve done fresh translations of the Smurfs, and we’re deep into it—that’s a franchise, too, but it doesn’t get the same level of attention that Asterix gets.

PK: I just realized I’ve been pronouncing it wrong all this time—it’s Asterix, not Asterix.

JJ: I guess I’m saying it in more of a French way, because I’m looking at the French all the time. Asterix, Obelix.

PK: What are some of the challenges and also rewards of translating this work in particular?

JJ: This has proven to be a difficult translation—especially the first volume, because of the fast turnaround time. And I’d say compared to comic books that American kids of the 21st century are used to, these are very text-heavy. There’s a lot more text going on in these stories than even in contemporary French comics, for that matter. There’s continuous dialogue, and what’s sometimes hard for me is there’s continuous puns and jokes—it’s pun after pun after pun. And so much of these are puns in French, right? There are sounds or sayings in French that you can’t just translate word for word for it to make any sense.

And sometimes it can be fun. [Goscinny and Uderzo] often included songs in the text—usually some song from the French songbook that everyone would know in the ’60s. They’d change the words to fit the situation. So that leaves us a choice. We can just translate the words, but usually, I’ll try to come up with a rhyme that’s something funny that links with the situation.

I got to do one recently, where Cacofonix, the bard, is walking through the woods singing a French scout song with the words changed—and he’s driving cows to curdle their milk and making animals flee because his singing’s so poor. I switched the French scout song to “The Ants Go Marching One by One,” but changed it from “ants” to the Latin word for ants, formicae farris.

That gave me room to play with it and come up with something fun, but it was still a joke in the original, so I created a joke in the translation there. I don’t make jokes where there isn’t one—that’d be pushing the original intentions of the author. They have a pacing in the story that I want to maintain.

PK: Perhaps one of the biggest differences, for readers familiar with the British translations, is the name of the druid: Panoramix instead of Getafix. Was the latter deemed slightly too edgy?

JJ: Most of the time, we’ve kept the names of established characters. Panoramix was the original name for the druid, which became Getafix in the British translation. And you know, wait a second, that sounds like he’s a drug dealer. But that’s not really what he’s about in the story. I’m not criticizing [Bell] at all—they had different ideas about what they were accomplishing and she had to satisfy the editor of the press she was working for, with different expectations—the times were different. But “Panoramix” carries over into English—why change that?

Sometimes we do have some back and forth [with the French publisher]. I remember a back and forth on what we wanted to name one of the Roman encampments. It was Babaorum, which is like a rum cake. We finally settled on Butterdrum.

PK: But Asterix’s village is never named, is it?

JJ: As far as I know, it’s never named!

PK: Maybe they left it unnamed so anybody in the vicinity could claim, “That’s our town.”

JJ: Hah, yeah, it’s just a little village, not far from the coast, in Brittany, in what they called Armorica then.

PK: Did you read the Bell/Hockridge translation first?

JJ: I never looked at it at all. I wanted to do a fresh translation. That was just me, Joe Johnson, how I speak now.

I know the editors keep an eye on it. And sometimes I’ll say, “Hey, this is problematic in the original, would you check this against what the British translator did?” That does come up occasionally. One time, it came to my attention that they had inserted a joke toward the end of one story. I can understand, it’s in the spirit of the books, but I think they had carte blanche to make stuff up.

PK: Whereas your approach, you mentioned earlier, is to keep the original pacing, so a joke would be in the same place, but maybe using an Americanism.

JJ: Yeah, I guess the trickiest thing is to come up with a joke that makes sense in the context, that doesn’t change the meaning of the original, but is still a joke.

There’s one set of adventures where Asterix and Obelix join a Roman legion because they want to rescue a young man that was drafted into Caesar’s army. So they meet a heterogeneous group of legionaries in training—Goths, a Brit, an Egyptian, a Greek. And any time a Goth talks, they use the Gothic font, and the Egyptian guy speaks in hieroglyphs.

So there was this one complicated joke, and I think we’re still waiting to hear from the [French] publisher about what we offered. There’s this little rhyming joke in French that means something like “by the hairs of your beard.” So they had the Egyptian responding with the hairy version of the hieroglyph! So what do you do with that in English? Because the joke just does not mean anything in English. So you have to come up with a different kind of joke that plays with the image that exists. It’s a challenge.

All these translations have been challenges in different ways. You have to think about who your audience is for a particular book. One of the sets of translations I was thrilled to work on for a long time for Papercutz was a renewal of the Classics Illustrated Deluxe series.

PK: I saw that in your CV—Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, etcetera.

JJ: Exactly. Sometimes it’d be a comic book adaptation of a French classic—so that would be the easiest for me, because it’s just me, Joe Johnson, translating The Three Musketeers into English. Yay, fun.

But other times it’s Mark Twain, Jack London, or Mary Shelley, where there’s an existing French comic book adaptation of an American or British classic that I have to translate back into English. Now, if anything in the French translation was a straight lift from the original English, that’s easy, I would take the original language and put it back in. But a lot of times, you might have, say, a two-page spread where Mark Twain had just written, “Huck and Tom played hooky and went swimming.” One sentence. But that was turned into a two-page spread in the French comic adaptation, with original dialogue. So then I’d get to create something that tries to sound like the Twain of that story.

PK: So you’re translating French dialogue to make it sound like Twain’s as we know it.

JJ: Exactly—and more in an updated English, and avoiding the traps of 19th-century American literature about race.

PK: My kids are way into Jules Verne right now. Did you do any Verne?

JJ: Yeah, we did Around the World in 80 Days as a Classics Illustrated Deluxe volume. Also a less-well-known Verne story called Captain Grant’s Children. These two kids find a message in a bottle that made its way back to England in the belly of a shark, to learn their father’s been shipwrecked.

And Jules Verne can be problematic too. For the 19th century, he’s forward-thinking—he was an abolitionist, he argued against colonialism. But he still puts caricature images of indigenous peoples on these trips. So this adaptation changes them all to animals. I thought that was a cool way to defuse the colonialism and racism that could be present for 21st-century readers.

PK: Yeah, when I read some of those classics to my kids, I have to do some framing and make repeated asides, like “Now, you know, from the Native perspective, the whites were the invaders.”

JJ: Yeah, there’s a shift when you realize that Captain Nemo’s not evil for sinking those ships. [laughs] He’s attacking the people who were colonizing his country!

PK: Speaking of which, this might be a stretch, but I’ve been wondering whether an American audience might have more sympathy for the colonized Gauls than the British would. I realize this is not an airtight analogy for a few reasons, but I’m thinking of a scene in Monty Python’s The Life of Brian when they’re clearly identifying with the imperial Romans and lampooning the colonized Israelites.

JJ: I don’t know. It never occurred to me. Certainly, the Gauls are looking at the Romans as being this occupying force, and I wonder sometimes if the Romans aren’t cast a little bit as being more like the German occupation of France. But I don’t think they go overboard with it by any means. The Romans are just people that are in charge, and they’re obnoxious, and, “If you see me patrolling the streets, you better say good morning or you’ll be in trouble.”

PK: When you mentioned the Germans, it reminded me: In the first book, the Goths say, “Ve’ll be back.” Was that a deliberate nod to The Terminator?

JJ: I don’t remember now—I’m eleven books in. Maybe I did think of it at the time. Or it may be that that was just the line in French!

There’s always a challenge, too, with these accent markers that are in the text. The German one’s easy because we [English speakers] have an idea what the German accent sounds like. But sometimes the book will make fun of local accents in French. Volume 11 is set in Arvernia, now Auvergne. The people in that part of France tend to pronounce s sounds as a sh. The book is rife with little jokes about that.

Finally, someone makes this dish with boar that Obelix is crazy about, and it’s got cabbage in it. The word for cabbage is chou. So they say “chou,” and because Obelix has gotten used to them making the sh sound, he thinks, “Why are they putting pennies in the boar?” Because he thinks it must be sou. But that won’t mean anything to American readers. So I’ve got to come up with something else. I might have to have a different ingredient. I think cabbage has got to go! [laughs]

PK: Did you study Latin at some point?

JJ: No, but I’m a singer in my Episcopal church, so I sing in Latin constantly.

PK: There are footnotes in the Papercutz editions providing translations for the Latin phrases that the Roman characters sometimes use. As far as I can tell, the original Asterix comics didn’t bother with that?

JJ: A lot of the Latin that appears in the original, they never footnoted it. It’s not explained. Now, some of the Latin phrases are famous—so if Caesar is saying, “Veni vidi vici.” Or “Alia jacta est,” the die is cast. These are well-known phrases. Or the Latin motto of Paris, Fluctuat Nec Mergitur. French kids will know that. So [Goscinny and Uderzo] relied on the kids’ cultural knowledge.

And a lot of times the Latin will make sense, between the context and the common roots of the Romance languages. But sometimes I wonder. For me, it’s easy to pull this up on the Internet and find, “Oh, he got this from Horace or Virgil.” But I don’t know what kids did in the 1960s or ’70s—again, there were no footnotes to explain the Latin.

PK: That’s why I think it was a wise choice to add the footnotes at the bottom of the page.

JJ: Yeah, and it gives us room to make jokes sometimes. Because sometimes the original does have a footnote in the panel itself, as part of a joke.

Here’s an example. There’s this rookie legionary with a patrol on the beach, where they see the Normans brawling with Asterix and Obelix, and they decide they don’t want to get involved because they don’t want to get pounded. So they go back to camp and have to chisel a report in triplicate on tablets. And the rookie guy says, “Hey, we’re supposed to be down there stopping this kind of stuff and maintaining the Roman peace.” So he goes and rats them out to the centurion.

The centurion sighs and says, “Well, you guys know what you’re supposed to do,” and sends them marching back to the beach to intervene in this brawl. And as they’re marching back, one of the experienced guys looks at the rookie and calls him a “fava bean” in Latin. In the footnote in the panel they explain, “This was a kind of bean commonly eaten by Roman legionaries, and the modern equivalent for this word in French is fayot”—which means a bean in French, but also means a suck-up.

It’s a sophisticated joke the French kids will get, but clearly it’s not gonna work in English. So I had the soldier call him a “caliga-licker,” and we printed in a footnote, “caligae were the kind of boots worn by Roman soldiers.” So then you do a back-formation and come up with boot-licker.

PK: Another footnote joke was where Panoramix was whistling, and the footnote said, “Old Gaulish tune,” then later when he was captured by the Romans, he was cursing, and the footnote said, “Old Gaulish insults.”

JJ: And the kids are looking at the picture as much as anything. I wonder how many kids will go to the footnotes and take it to heart.

PK: Well, that’s the fun thing about it for me as a parent. When I read Asterix with my 7-year-old son and 4-year-old daughter, we’re enjoying it on different levels.

JJ: And that’s the typical situation. The skillful author is somebody who can write for both audiences at the same time.

PK: I was wondering about the shades of meaning conveyed by different word choices, like “resolute” vs. “indomitable” to describe the Gauls in the introduction to each story. I want to say it’s the difference between “determined” and “unflappable,” or something.

JJ: I remember talking to the editors about this a couple weeks ago. Lately, I’ve been going with “die-hard.” Sometimes the same word in French has a slightly different emphasis in a given situation. It’s one thing for the narrator to say the Gauls are indomitable or resolute, and it’s another for a Roman legionary to describe them that way. So it depends on the circumstances.

PK: What’s your process? Do you read the entire original story first, or take it page by page?

JJ: For the first ones, I did read through the whole volume, then go back to start the translation. But usually I like to let the story unfold for me as I translate it. Typically, I have time after I’ve done that, I can go back and make sure it’s consistent all the way through. Sometimes, they may ask me, “Hey, we’re on a tight schedule, send us the first 10 pages.” So then I can’t go back at the end to do a big edit where I make sure things are consistent. I have to rely on the editors to do that part.

PK: Are you literally typing up a Word doc that’s basically the script? “First panel, balloon one.”

JJ: Right, that’s exactly it. I’ll go, “Page one, plate one, bubble one.” Decades ago, we settled on: How am I gonna present this so that the letterer and editor can see what’s going on? And I’ve just been doing it this way for years.

PK: Do you come up with the sound effects, too? Like “schplokk” vs. “kerplonk.”

JJ: The sound effects actually are a little tricky sometimes, because if you change it a lot, they’re gonna have to hire somebody to do that separate ink work, since the sound effects are outside the speech balloon. So the expense partly enters into it, and I don’t have control over the final product.

For instance, the sound effect in French for coughing is not at all the same sound effect in English. In French they may go “THEU,” which in French sounds like “chuh chuh chuh!” Because th is like a ch in French. So clearly that’s not going to work for English speakers; we need to see something like “koff koff,” or “cough.” But I don’t get to make the final call. It’s not like I can say, “Hey, we’re gonna translate it my way, damn it!” [laughs] But then I’ll see a review lay into me for it!

PK: I had an experience as an author when somewhere in the process the word I had written, “different,” got changed to “indifferent,” which means something completely, well, different! I’m still embarrassed. But I suppose once you’ve published 200-plus books, you get to have pretty thick skin.

JJ: You’re right, you do have to have a thick skin. Because I have asked myself, “Am I gonna look at the reviews for Asterix?” [laughs]

PK: Hopefully they’ll all be positive.

JJ: I hope so too. We have put a ton of work into this, myself and the editorial team.

PK: Any non-comics translations you want to mention?

JJ: I have branched out into more lengthy translations. A friend and I decided we were going to translate this 1845 French novel that had never been translated into English, called Friendship and Devotion, or Three Months in Louisiana, by Camille Lebrun. It’s about two American girls who were orphaned and brought up in a boarding house in Paris, going back to Louisiana and what they experience there. There’s an epidemic of yellow fever, but also they find out one of the two is mixed-race—in 1845 Louisiana, that’s a problem. So that’s why we thought this was an interesting novel to translate for our times. It’s racial fractures in America in 1845, and what do you do when you have an epidemic that’s killing people by the scores.

PK: Sounds more timely than ever on both counts.

JJ: Yeah, in terms of timeliness it was a little happenstance. But we’ve got this going and it will be published by University of Mississippi Press in 2021.

PK: Anything to add about Asterix? Reasons people should buy the new books?

There’s plenty in there for people to enjoy and to get acquainted with something that’s a cultural marker in the Francophone world. I think these are fun stories, and they have stood the test of time for a reason.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply