There is a monochrome Atín Aya photograph in which the marshy Cadíz countryside in southern Spain stretches into an endless horizon while dramatic clouds form overhead. The scene is framed by two muscular rustic buildings in the foreground. It is a view of Spain that would be recognisable to much of the rural population of its arid south throughout the country’s history.

Aya’s photograph portrays the country’s expansiveness, but also points to a phenomenon known as España vaciada, or Empty Spain, and the sad realities of rural depopulation. This was a result of urbanization, a phenomenon that transformed Spain, a nation slow to industrialize, throughout the 20th century.

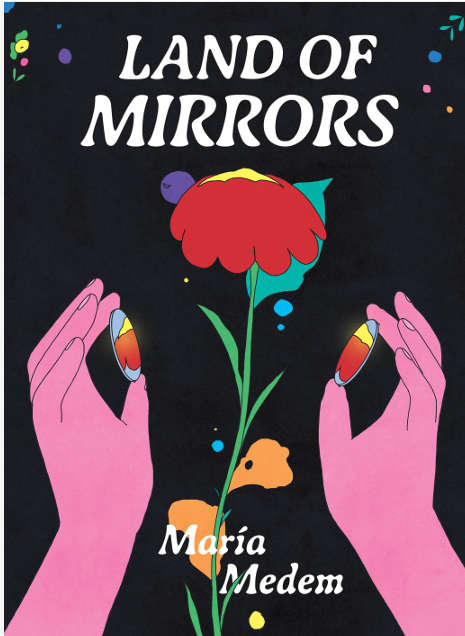

Aya is a photographer whom illustrator and comics artist María Medem has referenced as an inspiration. Few contemporary Spanish comics artists invoke Spanishness like Medem: Flamenco is mentioned in the book’s online blurb; she invokes the south’s expansive marshlands, the sort with which she is likely acquainted, having been raised in Seville.

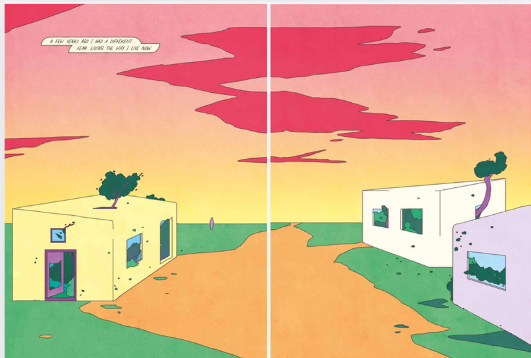

Indeed, this photo feels like an obvious reference point for the first double-page spread in Land of Mirrors, which appears just a handful of pages into the narrative, when we get a view of Antonia’s village, of which she is the sole inhabitant. Just before, we are introduced to Antonia as she is cutting up a pomegranate, another Spanish icon, noticeable through its art history as a symbol of Castilian power, as well as fertility, and the cycle of life and death. The allusion isn’t empty: Land of Mirrors, Medem’s second long-form narrative comic, revolves around the theme of rejuvenation, of a person and a land looking for a way to reclaim something they feel they’ve lost.

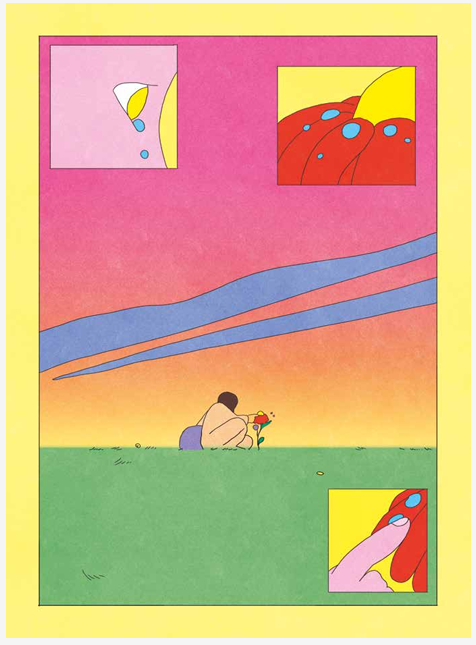

Amongst the ruins and the desertion, Antonia is caring for a solitary flower, whose existence seems permanently under threat thanks to the way things are in this environment emptied of people. Not much survives in this eerie landscape of muted primary colors and ombré skies of various tones. It is rather beautiful, but there is also a melancholy in the air.

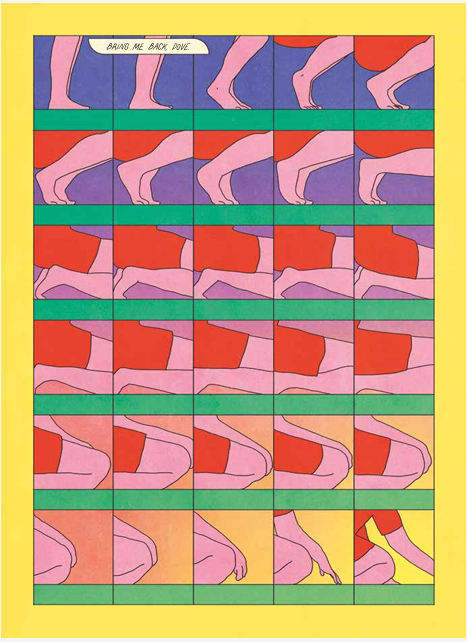

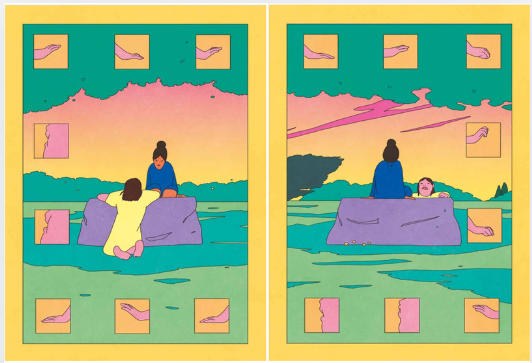

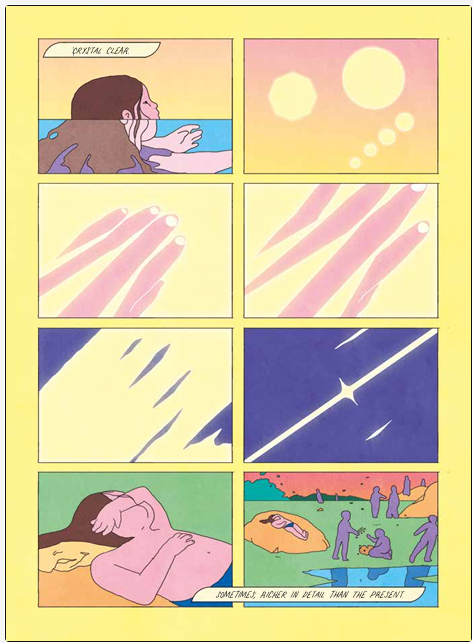

She lives in a world that she mostly interprets through sound. The birdsong, rustle of trees, the wind, and even that solitary flower have a collective, inherent rhythm. The panel arrangements sometimes represent the steady rhythmic nature of Antonia’s way of being and a sense of ambient musicality. One notable use of such ‘rhythmic panelling’ is when Medem utilises small, repetitive panels in picture frame borders to bring attention to a looping rhythm performed by hands.

Eventually, Antonia’s solitariness is interrupted by Manuela, a woman from a distant land who is collecting noises and who mostly communicates through song. Promised that Manuela’s home, the titular ‘land of mirrors’, a place of stories and folk traditions, contains some sort of method for strengthening the solitary flower, Antonia joins her on her trip there, where she aims to inherit the mystery and power of the mirrors.

The book’s opening salvos are its strongest. They’re small snapshots of a remote and rural life, and, in subtle ways, they communicate a sense of loss, of the soft changes noticed by people without distractions, and the way in which a person can be enmeshed within a geography and lose a sense of individuality. It leans closer to comics poetry than a plot-heavy graphic novel, a sense heightened by Medem’s play with forms and color and her invocations of particular sensations, such as a hand passing through water.

Medem employs a flat illustration style reminiscent of George Wylesol and Nadia Hafid. In Land of Mirrors, she makes full use of this style’s proximity to abstract formalism, and, at its most abstract (as well as in her interpretation of faces and people), it calls to mind the more painterly side of digital art, such as the work of Harold Cohen.

It’s a mostly metaphorical tale, so I expected a level of ambiguity, but the plot later in the book, when Antonia and Manuela embark on their journey, and then Antonia’s later experiences in the land of mirrors, feels underdeveloped. Key explanatory scenes appear to contradict each other (is the cultural use of the mirrors an in-joke or are they actually magical?). And characterization or key moments are referenced in the text, but don’t appear as part of the story. There are also some missed opportunities for creating an impact. Take, for example, the moment when our protagonists arrive in the fabled land of mirrors. The text tells us that “the light’s different on this side of the maze” and that “there’s so much activity”, but the visuals don’t reflect this at all; it takes 13 pages to get to a panel with more than three characters in it, and the coloring remains as dynamic as it’s been in the preceding pages.

The closing pages are a series of double-page spreads in which Antonia rides into the distance. Here, Medem is returning our focus to the horizon. She does this throughout the book thanks to her distinctive use of gradient skies. These backdrops are very reminiscent of the sceneography in Carlos Saura’s trilogy of flamenco movies.

Saura’s landscapes are often interpreted as abstract, decontextualizing the story’s characters and plot, a move away from the “politics of representation” which typified his Franco-era work. But is it really the case that depictions of landscapes in this way are purely aesthetic abstractions? It’s true that Saura, and now Medem, are indebted to surrealism (which can sometimes be confused with depictions of the purely make-believe), but even Dalí’s seemingly unreal landscapes were often literally landscape paintings, based on views along the Catalan coast. It’s reality’s unrealness, the discomfort it can cause, as well as its magic, that is on display here.

Backdrops such as those Saura and Medem employ aren’t simply aesthetic backgrounds to bring attention to the foreground. In Cristina García Rodero’s depiction of the Spanish countryside (another photographer that Medem has noted as an influence), the distant horizon is part of the story. It is the land that has sustained the people on it; contemporary viewers also know it is a land that has been, or is being, emptied. There is a toughness to the landscape which we interpret to say something about the people depicted in the photo, but the people themselves, over generations, have helped shape the land, by farming on it, building on it, their stories and songs imbuing it with meaning. Urbanization also tends to result in ahistorical myth-making about rural culture, as cultural memory is performed and mediated in a new environment, and urban populations often generate a nostalgia for a pastoral lifestyle that often never really existed in the way it is imagined.

Saura represents this empty, endless horizon in cinematic color, in a manner apt for a mentee of Buñuel, tinted by dramatic reds (as is the case in his 1986 version of El Amor Brujo). It is an exaggerated realism that reinforces that drama and the passion associated with a stereotypical perception of this geography and its people. These flamenco movies were made at a moment when the sorts of communities had been transformed by modernity, in both modernity’s liberal socialist and fascist forms.

Land of Mirrors is not a story about these sorts of historical changes specifically. It is a book in which people are self-sustaining without a wider economy or even an acknowledged deeper political context. In this sense, it is a fantasy. But this fantasy world is a canvas in which Medem riffs on themes of isolation, community, concerns around leaving a positive impact, and desires to assist nature, informed by the landscapes which, in our real world, have become synonymous with depopulation and concerns around futurity.

That distant horizon into which Antonia rides is a reflection of her distance from others, and carries the weight of her sense of self, herself being a self-sustaining force that has frontiers to explore. We should not mistake the expanse as emptiness; it has a history. It contains stories, and we tell ourselves stories about it. The people and the land are in a cyclical relationship of cohabitation and meaning-making. The French may refer us to the broadest conception of terroir, the interplay between land and people. Land of Mirrors is about the emotional solutions some look for in order to mitigate the worst impacts of modernity upon a communal world. Here, the expanse is not only a place of memory but also an opportunity for return and regrowth.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply