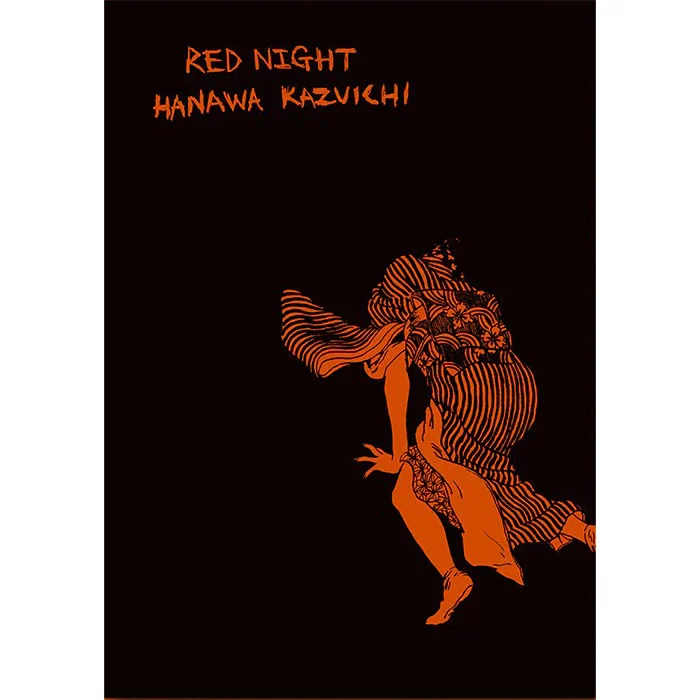

A short list of things that you will find within the pages of Red Night (Hanawa Kazuichi, translated by Ryan Holmberg, Breakdown Press): Blood, gore, murder, torture, rape, paranoia, assault, assault with a deadly weapon, child abuse, sexual abuse, mental abuse, physical abuse, really-every-kind-of-abuse, bestiality, stalking, child endangerment, monsters, demons, pain, disease, suicide, self-mutilation…. A cornucopia of the worst humanity has to offer, in the starkest black and white art you can find. This isn’t Johnny Ryan cartooning, nor the even-handed pencils of Jacen Burrows; this is in-your-face, in-your-guts, in-every-hole-in-your-body-at-once type of comics.

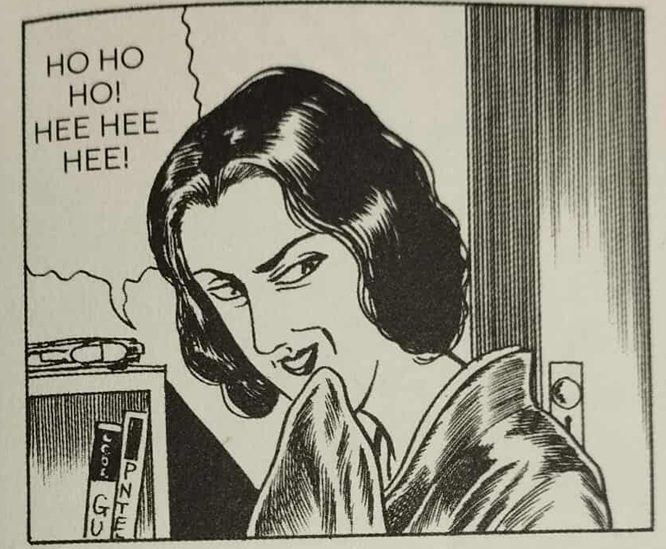

It’s also a funny book. I laughed at Red Night more than I laughed at most would-be humor comics; and not the laugh of mockery, not the laugh of “I am better than this”, nope, I laughed with the material. Hanawa Kazuichi should be put on the line with Jonathan Swift for his ability to mine human suffering into the bleakest, blackest, humor.

It is rather obvious why the former aspects of the Red Night (torture, abuse, etc.) would overwhelm the latter (the gags). The transgressiveness is the (selling) point; to quote from the marketing copy: “In Hanawa’s work cruelty and decadence go hand in hand, and desire is accompanied by a macabre twist.” Which isn’t to say Breakdown Press is selling you a pig in the poke, the book is a dance macabre in comics form. If you come for brutal violence and gore – you will not leave unsatisfied. If you come for a rejection of every social and political norm — you will also get your wish. To me, however, nothing left quite an impression as Hanawa’s sense of humor.

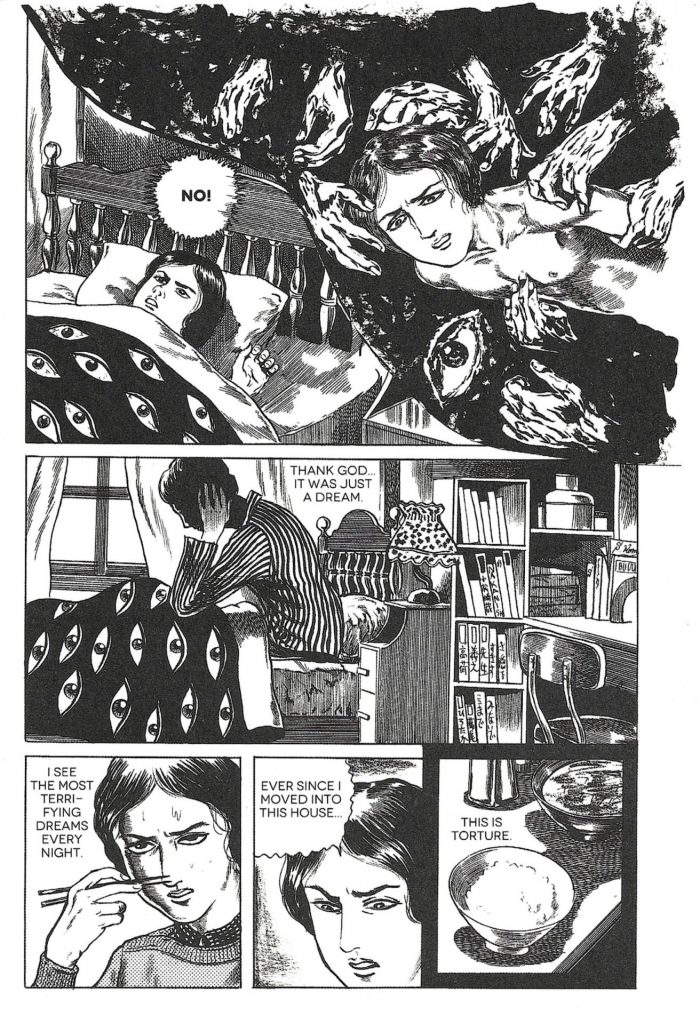

Let us contemplate one story: “The Disgusting Cockroach Boy.” The title alone primes you for comedic exaggeration; this isn’t merely the story of a Cockroach Boy but of “The Disgusting Cockroach Boy,” as if one wouldn’t expect a Cockroach Boy to be disgusting. Or maybe the author wishes to signify that this Cockroach Boy is even more disgusting than usual. It begins as many horror tales do, with a young man transferring to a new place (the house of his aunt, whose son died in mysterious circumstances); the house is smelly, infested with cockroaches, and has a general unpleasant atmosphere. So far, so conventional – you can imagine H.P. Lovecraft doing something similar (“The Rats in the Walls”) or Edgar Allan Poe (“The Fall of the House of Usher”), though there is no pretense of fallen nobility; it is a poor person moving to an even poorer house. Likewise expected is the revelation that the supposed dead child is actually alive in a monstrous form. Yet as the story rises to a crescendo, it just… stops. There is no struggle between the human boy and his cockroach counterpart, no further twists or turns. Instead of drawing to a conclusion, the author gives us a caption box: “What atrocities the poor boy thereafter suffered defy imagination… I end this story here out of pity for your fragile soul.”

Considering the rest of the book, it seems unlikely that Hanawa is actually in a mood to spare “your fragile soul”. His maximalist style never avoids that which could be shown, and never blunts its sharp ending. No, “The Disgusting Cockroach Boy” works because the ending is so sudden and meaningless. The joke is about the surprise, and that surprise is about the subversion of expectation. In the case of many of the stories in this collection, what is expected is any deeper meaning. A revelation about some “proper” reason for the transformation of the Cockroach Boy, a family curse caused by some wicked action of a past ancestor, would make the story into a tragedy. Yet there is no real reason for it, nor is there any reason for the boy to hate his relative other than our protagonist not being a Disgusting Cockroach Boy himself. These ugly, horrible people are exactly what they appear to be on the surface. Do you need a reason for people to be cruel and hateful? Do you need to ponder the depths of the human soul, as Freud did? There are no depths here; we are all meat machines, slouching towards our demise.

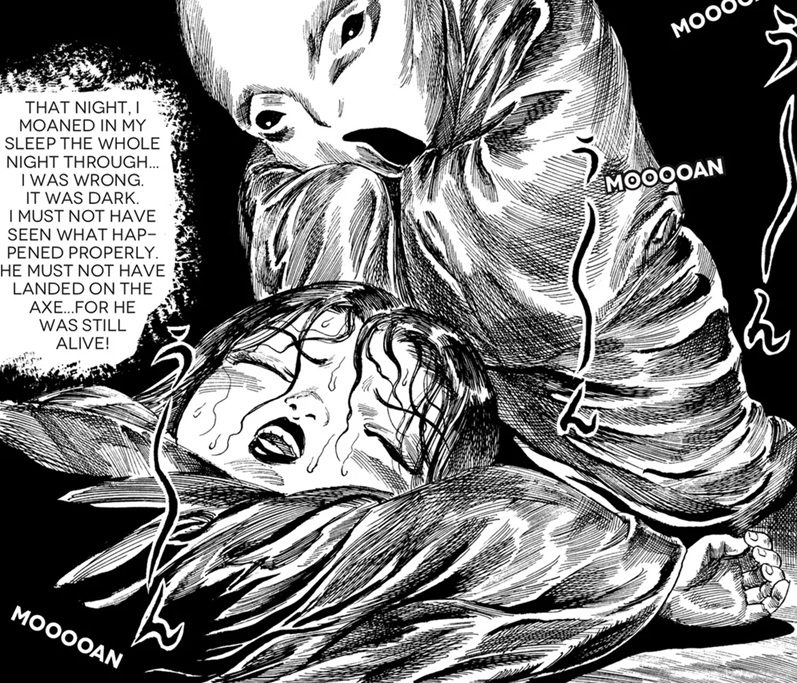

Take, for example, the opening story, “Red Night”, which features an extremely elaborate scheme by a woman to enact vengeance on her husband, an abusive creep who goes out at night to kill people randomly. After begging him to stop his bloody deeds with little success, she dons a disguise and goes out to meet him at night; he kills what he considers to be another random stranger, only to discover he killed his wife. Deciding that a “Romeo and Juliet” ending is the best he can hope for, our wandering swordsman commits suicide; at which point the woman stands and reveals she was wearing an armor – she knew that he would kill himself. Thus, she walks away content in her bloody victory.

You can also do the exact same story as a tragedy, one could certainly imagine several of Hanawa’s coworkers in Garo doing something similar in a more straightforward manner, but “Red Night” succeeds by taking all these classical elements and charging them to nth degree. The husband isn’t merely an abusive man (you can imagine Tsuge or Tatsumi writing the killer as a sad sack trapped by social circumstances), but an outright serial killer. His suicide isn’t an honorable seppuku, after failing to merely stab himself he picks up the blade of his sword in his mouth and runs directly into the wall Loony Tunes-style (only with much more blood). Hanawa’s weakness as a storyteller – everything in his style is exaggerated to such a degree that, while the thrust of the scene can be understood, individual occurrences on the page are oft left vague – actually helps in this case, adding to the sense of a world run amuck. And, of course, the man dies for nothing. His suicide doesn’t purify his soul or prove his worth. He’s going to be just another body rotting in the ground.

Hanawa writes and draws an ugly world, but more than that — he creates a world of moral vacancy: a world in which all pretenses of nobility found in a traditional society are cast aside. The old hypocrisies are laid bare; It’s a dog-eat-dog world.

In the two-parter “Jar Baby”, the structure of the story becomes truly Byzantian, causing the reader to wonder what the connection between part 1 (concerning a mysterious baby found by a poor couple) and part 2 (concerning the growing obsession a whole village develops with the heels of a noble lady) is. “Jar Baby” might be the best story in the collection, with the totemic importance attributed to the legs of the noble lady dragging people into more and more ludicrous actions; the story ends up circling back to itself in a perfect sphere of pain -– every act causes pain to someone else, who causes further pain in turn. We end with the mother of the baby walking blissfully unaware as her demonic child eats a person alive: “I think about the child sometimes when wandering around the capital… not that I give a damn though!” – just like that noble lady who lived her life completely unaware that her mere existence was like a gaping wound in the life of that poor village.

Such is the work in Red Night, it is also a blade, cutting a gashing wound into our psyche. Sometimes these wounds heal and teach us a valuable lesson. But sometimes they just keep gushing out blood until the body and empty and nothing else remains. Hanawa’s creation is a two-sided blade; however you hold it – it is going to cut you.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply