At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, social media was saturated with viral posts celebrating dolphins and swans “returning” to the canals of Venice and elephants passing out drunk in a tea field in China. Nature, it seemed, was flourishing in our absence. One by one, all of these news stories were debunked. The photograph of the dolphin was taken in Sardinia, and the swans in the canals of Burano, where both are commonly present; the photo of the elephants was taken pre-pandemic, and the elephants were only resting. Nonetheless, these posts and others like them, described as the “Coronavirus nature genre” by New York Times columnist Amanda Hess, spread like wildfire. Hess argues that while these posts “tiptoe to the edge of eco-fascism” (and perhaps more than tiptoe in the case of @ThomasSchulz’s famous tweet declaring “we’re the virus”), the genre’s mass appeal stems from “subtle massaging of the human ego. It feeds the fantasy that centuries of environmental abuse can be reversed by an abbreviated period of sacrifice.”

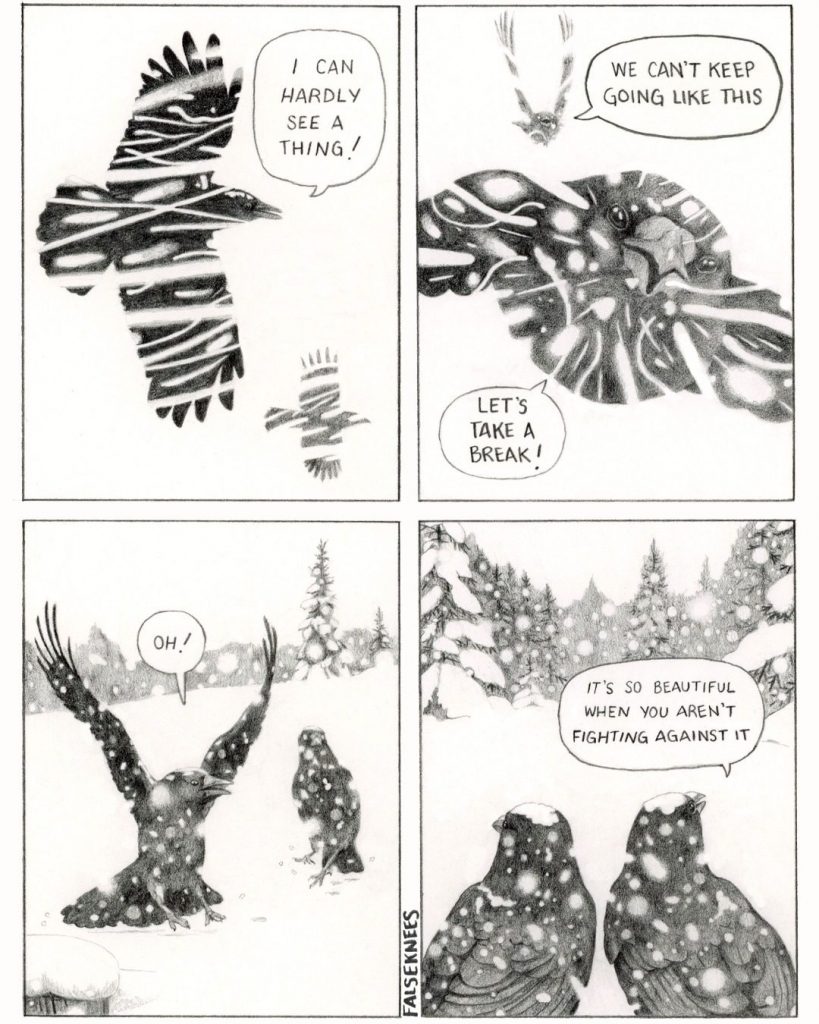

Sandwiched between fake nature news, memes making fun of the fake nature news (e.g., a Lisa Frank dolphin with the caption “nature is returning”), and photos of sourdough loaves, many netizens no doubt came across False Knees during their 2020 doomscroll. False Knees, a comic strip starring anthropomorphic birds, is the brainchild of Canadian cartoonist Joshua Barkman. Barkman’s birds are humorous, sweary, and often profound. For example, one poignant strip from January 2025 features two crows flying through the snow and ends with one crow’s poignant realization that “it’s so beautiful when you aren’t fighting against it.” It’s a statement one could easily apply to life. Since 2020, Barkman has also created an annual comic that releases daily over the course of a month, a tradition he’s variously dubbed “Falsetober” and “Kneesvember.” Like Barkman’s False Knees strips, these longform stories focus on anthropomorphic wildlife. His Falsetober 2022 comic, Spores, saw animals gain the ability of interspecies communication via a magical fungus and was nominated for an Eisner Award in 2023. Among the hundreds of comics I read last year, one of the books that left the biggest mark was Barkman’s 2024 Kneesvember comic. Eventually titled Life After Life, it was nominated for an Eisner and won.

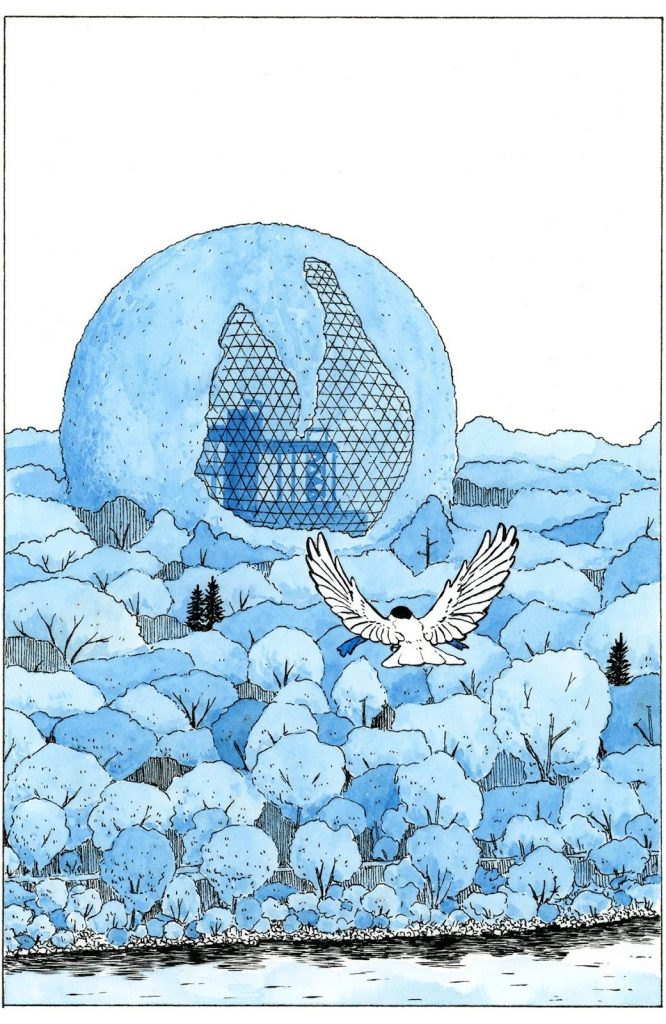

A story recalling “Coronavirus nature genre” headlines, Life After Life follows three talking black-capped chickadees named Pips, Patches, and Fuzzie as they adventure across post-apocalyptic Montréal in search of airplane peanuts. Like many of Barkman’s other Falsetober/Kneesvember efforts, Life After Life has a highly limited color palette, using only India ink and blue gouache on white paper. This palette intensifies the comic’s sense of serene melancholy. It’s hard to imagine a more stereotypically sad color than blue; a sad person may even be said to be feeling blue. But here blue isn’t just the color of “feeling blue”: blue is the color of vast expanses of water and sky. Blue is the color of attacking blue jays.

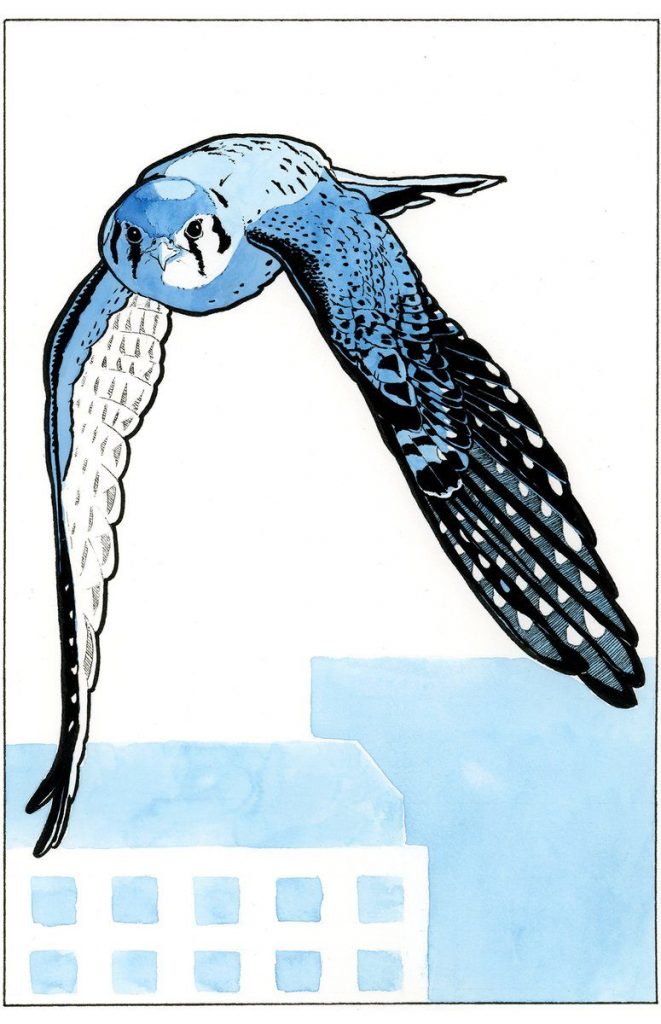

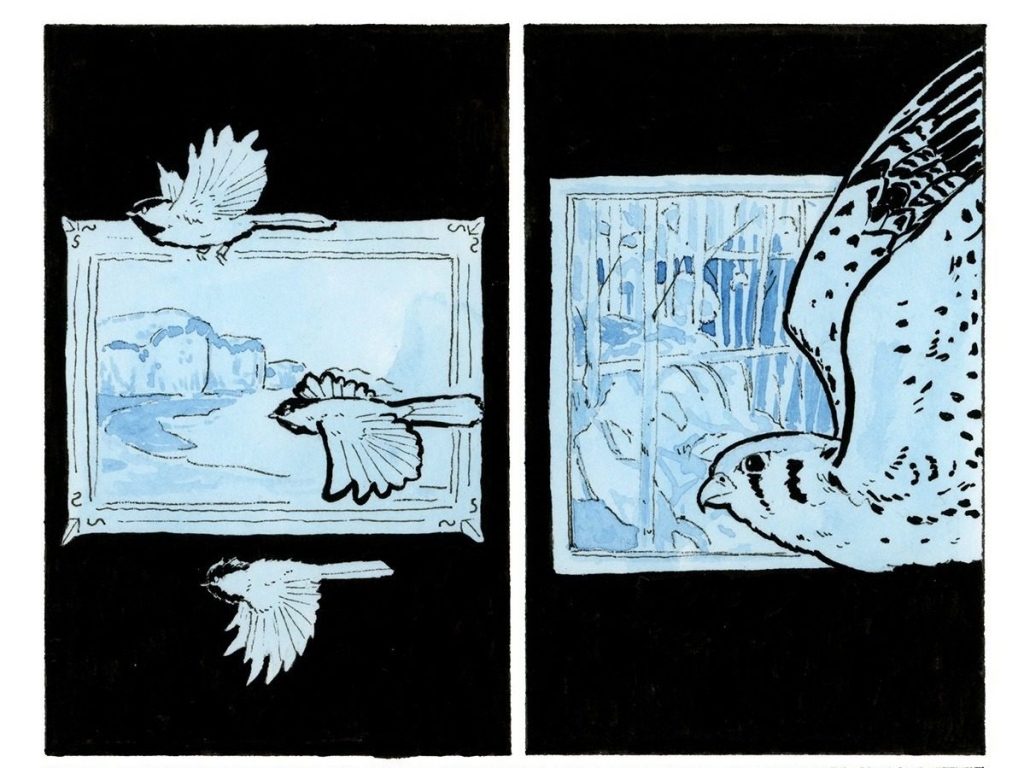

Barkman’s appreciation and mastery of his avian subject matter come across in every panel. His artistic approach to birds is generally quite realistic, with Life After Life’s three protagonists helpfully given distinguishing characteristics: Pips has bands on her legs put on by a scientist, Patches has white patches throughout her “cap,” and Fuzzie is—you guessed it—fuzzy. Other birds and wildlife are treated with equal thoughtfulness, with the aggressive blue jay in the opening scene (Nov. 1) and a majestic-yet-menacing merlin (Nov. 19) being two standouts.

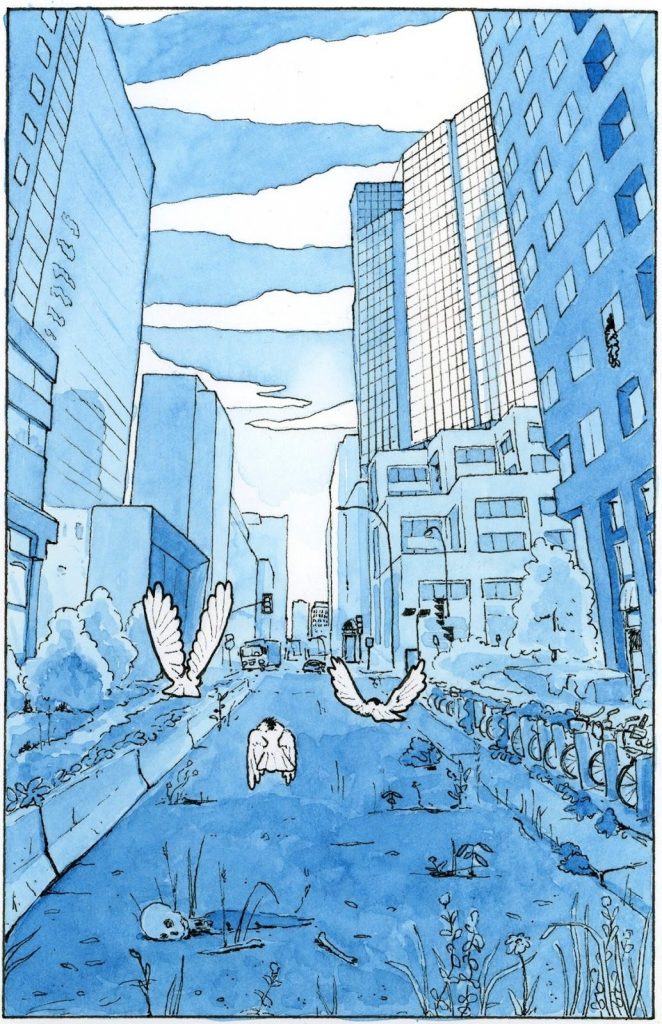

While the concept of Apocalypse is ancient, the birth of the modern post-apocalypse genre is generally attributed to Frankenstein author Mary Shelley. Inspired by personal loss and a then-ongoing cholera pandemic, Shelley’s 1826 novel The Last Man is the tale of a man named Lionel Verney living in the 2070s who loses his loved ones one by one as an unstoppable plague sweeps the globe, leaving only Lionel alive. In the novel’s closing chapter, Lionel arrives in Rome to find “sheep… grazing untended on the Palatine, and a buffalo stalk[ing] down the Sacred Way that led to the Capitol.” While less neoclassical, Life After Life is teeming with similar scenes: raccoons have taken up residence in a dilapidated apartment building (Nov. 8), a woodland thrives around a bus that crashed into a tree (Nov. 10), and deer graze on an overgrown highway dotted with cars whose drivers are long since dead (Nov. 8). Most are done as splash pages, inviting the reader to slow down and immerse themself. Put in the position of Shelley’s protagonist by Barkman’s art, it’s hard not to be hit by the same thought that hits Lionel in The Last Man: “Yes, this is the earth; there is no change—no ruin—no rent made in her verdurous expanse; she continues to wheel round and round, with alternate night and day, through the sky, though man is not her adorner or inhabitant.”

While The Last Man was a critical flop in 1826, post-apocalypse fiction has grown increasingly popular in the intervening two hundred years. In recent years, the pandemic, climate change, and the Doomsday Clock ticking ever closer to nuclear midnight have made it hard to avoid a sense of world-ending doom. Our fiction landscape across media has become increasingly saturated with narratives imagining what the world will be like when we are no longer in it. Just as The Last Man was a reflection of Shelley’s present, our fiction—frolicking swans and drunken elephants included—reflects our own. In recent years, works like the Oscar-winning animated film Flow (2024), the hit video game Stray (2022), and Life After Life have eschewed humanity altogether from these narratives in favor of animal protagonists. In the 2019 post-apocalypse video game Overland, “All Dogs Mode” allows players to replace all human characters with dogs. The only human observers of these fictional post-human worlds are their audiences. And in all of these narratives, the absence of humans can make things all the more nerve-wracking, leading one Instagram commenter to call Life After Life “chickadee Watership Down.”

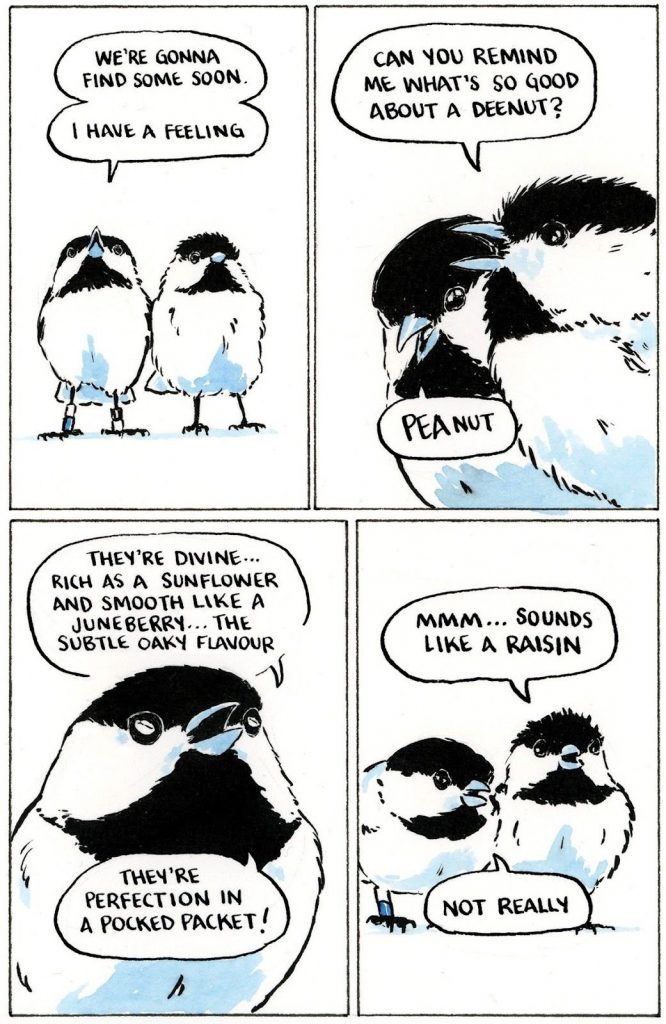

While Overland’s dogs bark and Stray’s and Flow’s cat protagonists meow (Stray famously has a dedicated “meow button”), Life After Life’s chickadees speak English and crack jokes—an uncanny contrast to the human skeletons littering the landscape. The juxtaposition of human voice and realistic bird is part of what makes False Knees and its antecedents so successful. In the case of Life After Life, it both amplifies that humanity has gone extinct and makes the morbid reality bearable. The “memento mori” of it all might be oppressive were it not for the comic’s comedic aspects, like Fuzzie referring to people as “deeple” and peanuts as “deenuts” or Patches imagining the airplane as the skeleton of a massive deceased bird (Nov. 25).

These works aren’t simply post-apocalypse fiction but specifically post-Anthropocene (Anthropocene being the current human-dominated geological epoch). They concern a time that isn’t post-everything, merely post-us. As unpleasant as it may be to consider, humanity will one day no longer exist. Our end may come about by our own hand, taking the form of nuclear war or climate change, but it may just as easily be the sort of vast and sudden cataclysm that befell the dinosaurs. In Life After Life, the exact cause of our collective demise is never stated, though something sudden seems most likely given the number of skeletons paused mid-action (e.g., driving, riding on a bus, walking through a doorway), which collectively give Montréal a Pompeian quality. Discussing and imagining the post-Anthropocene means to consider our collective impact on Earth; will our existence have left it the better or is ours a legacy of destruction and degradation?

Life After Life is neither scathingly cynical nor profoundly hopeful in its pronouncement. In the comic’s landscape, spectres of industrialization like the abandoned Five Roses flour mill abound (Nov. 17), all since reclaimed by plant and animal life. Simultaneously, Barkman’s narrative stresses the ways in which humanity has loved and tried to protect the natural world. We see this both in a surreal scene where a merlin flies past landscape paintings in the now derelict Montréal Museum of Fine Arts (Nov. 21) and equally when Pips reflects on getting bands put on her legs by gentle conservationists (Nov. 11). In one of Life After Life’s most haunting moments, the chickadees soar towards the overgrown ruins of the Montréal Biosphere, an environmental museum that here feels akin to the ruins at Hiroshima Peace Memorial or Chernobyl (Nov. 9). A monument to ecological conservation, the message of the Biosphere ruins seems clear enough: the best thing we could do in the end was get out of the way. But then again, perhaps it’s works like the Biosphere that allow plants and animals to thrive after us in the first place.

In their article “Post-Anthropocene Conservation,” ecologists Maggie J. Watson and David M. Watson assert that “it is the arts rather than religion or science that has given most thought to a post-human world. Science has contributed little to this discourse.” Life After Life contributes to this ongoing conversation. However, Watson and Watson stress the importance of approaching the concept of post-human Earth from the perspective of conservation science. Watson and Watson’s article is in some ways cynical, quoting Chernobyl researcher Jim Smith: “We’re not saying radiation is good for animals, but we’re saying human habitation is worse.” However, Watson and Watson stress — much like Life After Life — that “life will persist. Visit a toxic industrial area or war-ravaged ruins and there will be life in the rubble: a dandelion, an ant, maybe a passing pigeon… No matter how humanity ends or how much we degrade the planet during our demise, life on Earth will continue. We take great solace from this realisation.” When Life After Life’s chickadees themselves discuss the shifting ecological balance, it is, ironically, the pigeons that are one of the only named non-human casualties, their populations decreasing while birds of prey have grown more common—and endangering the lives of the comic’s chickadee protagonists.

The cynical view of humanity-as-ecological-net-negative (“the earth is better off without us”/“humanity is the virus”) is undoubtedly a fatalist one. It is also one associated with ecofascism, a term Elaina Hancock broadly defines as “any environmentalism that … reinforces existing systems of inequality or targets certain people while leaving others untouched.” In his book The Problem with Black People: On race, identity, and systemic oppression, Black Asian climate activist Angelo Louw emphasizes that ecofascists “don’t mean all humans when longing for this mass extermination, they mean human beings having babies at a ‘disproportionate rate’… they are referring to us: the Black and Brown people of the world.” As numerous environmentalists have pointed out, population control—popularized in the 20th century by ecologist Garrett Hardin’s widely-taught article “The Tragedy of the Commons” and Paul Ehrlich’s book The Population Bomb—has long been used within environmentalism to justify eugenics towards people of the global south. It is also, quite obviously, incompatible with the pro-choice movement and disability rights. In recent years, there have been calls to reexamine the racist legacies of Ehrlich, Hardin (a eugenicist and white supremacist), and earlier environmentalists like Madison Grant and Gifford Pinchot. The Sierra Club, which originally published The Population Bomb, no longer supports population control.

Thanks in no small part to the hard work of marginalized people in environmentalist spaces, the conversations we have about humanity’s relationship with nature are changing. As both Louw and the Sierra Club note, the United States and Europe are, in fact, responsible for a majority of natural resource use, with marginalized communities being disproportionately affected by climate change and environmental issues like access to clean water. The question remains: what is to be done? That answer is obviously a complex one — too complex for an essay about a webcomic about birds. But at its heart, it is a matter of seeing ourselves as in community with one another and with the natural world, rather than embracing cynicism, misanthropy, and the politics of ecofascism. In The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World, Potawatomi ecologist Robin Wall Kimmerer argues for looking to Native lifeways and adopting a gift economy, which means learning to recognize when we have enough, what we may give to one another, and what we may both give and receive from the natural world. Watson and Watson end their article with a call to action for their fellow environmental scientists: “choose a lineage or a place that you care about and prioritise your actions to maximise the likelihood that it will outlive us.” I’d like to think this is a plea that extends beyond the scientists for whom it was originally written. For Barkman, it’s obviously birds.

I must admit that the month I spent reading Life After Life and the months I’ve spent writing this review have also made me think not infrequently of my dad, himself an ecologist. This is somewhat ironic, as my dad tends to avoid climate fiction in his free time. Since my childhood, my dad has always stressed the importance of the natural world, our place in it, and learning as much about it as we can. Sometimes, that meant him quizzing me on tree identification at rest stops on road trips. In third grade, it meant helping me put together a tri-fold poster of photographs I’d taken and facts I’d compiled about the birds in my backyard. My dad likes to imagine that the things he plants now (his example is always an acorn, though he specializes in Indiana’s native plants) may be the very reason that species survive our extinction. I’m grateful to my dad for giving me this, as I’m grateful to Life After Life. While it may be a humorous comic about talking chickadees searching for “deenuts,” Barkman’s comic provides a vital reminder that our earth is precious and our time here is limited, so we must do the best with what time we have left.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply