In her essay ‘Social Abstraction: Toward Exhibiting Comics as Comics’, Erin La Cour describes how “comics in the space of art galleries and other cultural institutions have been treated as sociological archival material or cultural artifacts in contrast to art.” She describes how “comics encased in glass […] point to their elevation as precious works of literature […and] as archival material only to be handled by experts.” Those of us who have been to comics exhibitions will recognize this description. The sense upon entering the gallery or museum that we’re meant to take this all very seriously now, as we trudge through the geographical and chronological clichés while nodding knowingly at an original Schulz or Moebius.

There is a benefit to approaching comics like this at some point, but comics history and public exposure to the medium have become entombed by this framing. In trying to pitch itself as both literature and art, comics has become a victim of its own success, oftentimes overwhelmed by the pretensions of the gallery or museum when presented in that context. La Cour argues that the “social abstraction [of comics], achieved through withdrawing from both art discourse and comics’ material embodiment on the page and in the book, can be instrumentalized to move closer to a means of thinking of and exhibiting comics in a manner that engages with their affective qualities.” In short, we should stop fetishizing the page and investigate how the strange language of this medium has been and is being explored, and how it is allowing artists to explore the times they live in, which would simultaneously reveal the medium’s actual artfulness.

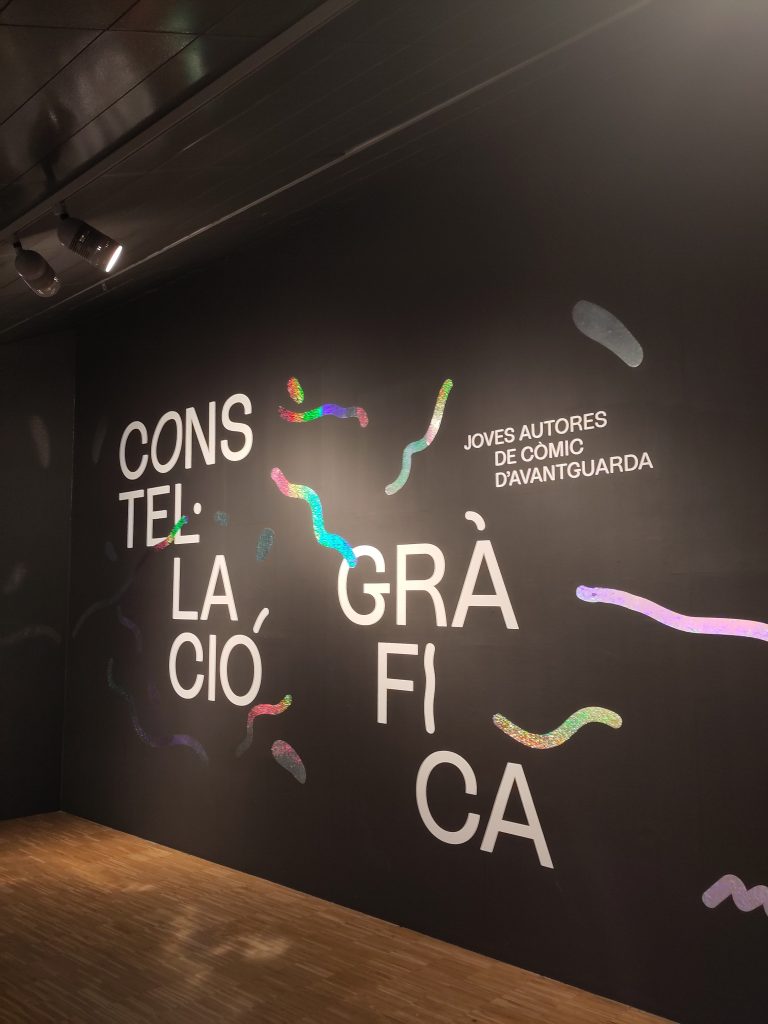

Graphic Constellation: Young Women Authors of Avant-garde Comics, on show at the CCCB in Barcelona, Spain until May 14, is the first comics exhibition I’ve gone to that takes this challenge seriously. I’ve no idea if curator Montserrat Terrones has read La Cour’s article, but in developing a show around Bàrbara Alca, Marta Cartu, Genie Espinosa, Ana Galvañ, Nadia Hafid, Conxita Herrero, María Medem, Miriampersand, and Roberta Vázquez, she has seemingly found it essential to expand on and draw attention to the essence as well as the material of comics.

The nine women who are curated here represent a slice of a contemporary Spanish comics scene that is dominated by women who are producing work that is setting the tone both in their native country and whose styles are becoming influential (and copied) internationally. Graphic Constellation feels like an exhaustive trip through the spectrum of contemporary themes, styles, and moods, and yet we still miss out on the likes of Flavita Banana, Ana Penyas, and Moderna de Pueblo, which tells you something about the quality and quantity of Spanish comics being made by women at the current moment.

The social and political framing of these nine authors is the first thing the exhibition does, and it is refreshing to see a cultural studies approach being taken to the medium. This is in stark contrast to another comics exhibition that was in town recently. Comics. Dreams and History at the CaixaForum featured all of La Cour’s bugbears and even more frustratingly had a room of original art from DC and Marvel which you weren’t allowed to take photos of because of copyright infringement issues (providing yet another reason to swerve the Big Two). Graphic Constellation instead starts off with the local context. Very local, in fact, as it has interviews with four Barcelona institutions: Pablo Taladro, one half of the team behind the printers Maquina Total; Nico Rodríguez, the proprietor of comics and zine store Fatbottom; Silvia Aymi, one of the founders of GRAF Fest; and Toni Mascaró and Sergi Puyol, publishers at Apa Apa. Not that the scene is provincial, mind you. Taladro talks about developing his love of fanzines in the Uruguayan punk scene he came of age in, and Aymi explains how GRAF was developed to be a local equivalent of SPIN OFF Angoulême and Small Press Expo.

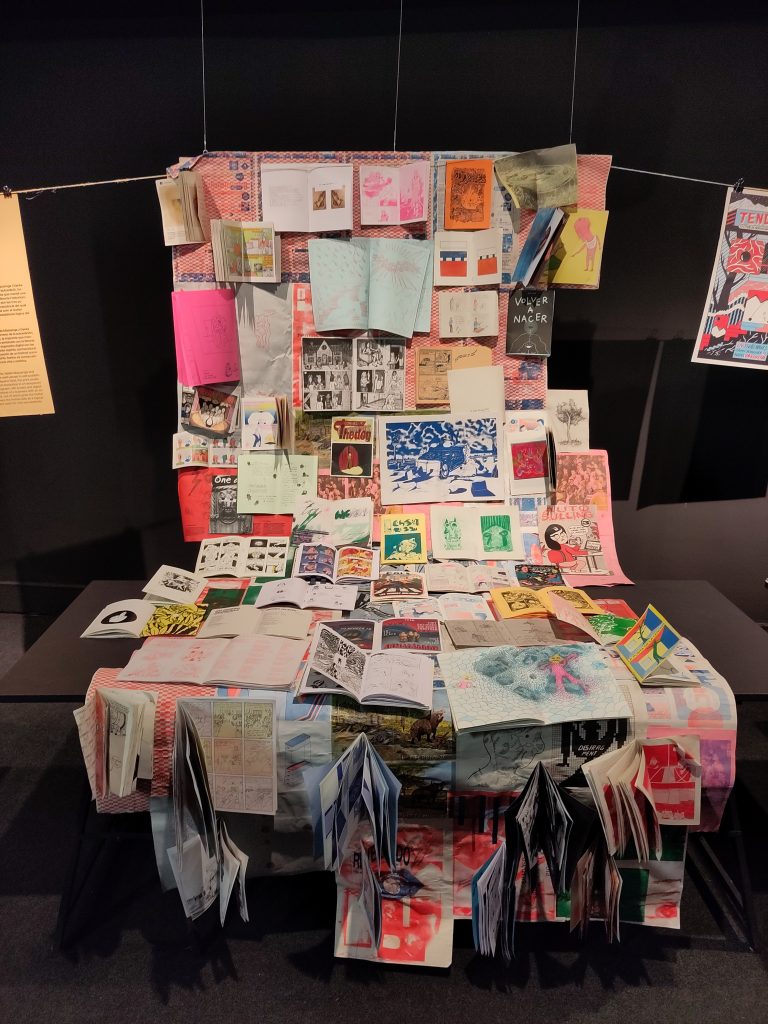

Visitors are presented with an interactive library of zines and books from a range of authors and artists including Olaf Ladousse, Olivia Cábez, and Gabri Molist. The wider context and influence of Anglo- and Francophone comics and manga is briefly touched on, with special attention being drawn to Marjane Satrapi and Julie Doucet, and, to a lesser extent, Simon Hanselmann, Lisa Hanawalt, and Dash Shaw. I was somewhat surprised that Lynda Barry, Aline Kominsky-Crumb, and Alison Bechdel weren’t prominent names here, and neither were Spanish legends such as Nazario or Joan Cornellà, but space is limited, and the exhibition does end with an animated video of “constellations” of artists from across the comics spectrum, which is an intriguing way to map out the various corners of comics’ heritage in a non-linear fashion.

Given that this is an exhibition about “young” artists, the other social framing comes in the form of a room designed to explain millennials and their social milieu through a video montage, three screens showing irony-laden ‘doomer’ memes, and an installation piece that must surely be an homage to Tracy Emin’s My Bed. This is a facsimile of a bedroom, unmade bed included, with various books, pharmaceuticals, and tote bags with slogans left around. As a millennial myself, I found the aestheticizing and generalizing of my generation’s experience (in the West, at least) all a bit uncanny valley. I guess with Gen Z quickly becoming the dominant collective engine of culture, we millennials are due to become museum pieces any time now. Having said that, with the early 2000s being back in fashion already, it looks like trends are set to repeat at an increasingly frenetic pace so that in the end we’ll all just keep microdosing abstracted versions of events that we can’t even remember the original incarnation of.

Following this, we find the main attraction, in which nine rooms focus on each of the nine artists in turn. These rooms do include the typical presentation of original art framed and hung on the wall, but they do also have blown-up versions hanging from the ceiling. Each room starts with a video interview with the featured artist, in which they generally discuss their influences, process, and thoughts on the industry. Some of the rooms also include screens that show digital art and animations that these artists have produced alongside their comics practice. The main elements of this exhibition that push toward La Cour’s “social abstraction” are the original installations that conclude each room. These provide the artists opportunity to expand their worlds beyond the page and recreate their vision and comics practice in a multimedia fashion.

Roberta Vázquez (who in her interview clip tells us “I’d just like to pay my bills one day!” and references Robert Crumb and legendary Spanish comix magazine El Víbora) takes the anthropomorphized animal characters that appear in some of her work and reapplies them to a board game/comic crossover similar to what Chris Ware does with those arrows he uses. It’s printed onto the floor, so visitors can traverse it, and arrive at statuette versions of her protagonists. Vázquez is one of many artists featured here, Espinosa and Galvañ being two others, who have produced zines to which many of the other artists featured here have contributed.

Bàrbara Alca is one of the few artists here whose portfolio fluctuates between different visual styles, but Hanselmann’s influence is the most noticeable, though Alca’s style of humor is less infused with marijuana. Her installation is a padded room with a large interactive screen at the end where Alca presents Cringer, her alternative to Tindr, with various profiles she’s come across reimagined and drawn, original cringe-inducing profile texts included.

Genie Espinosa’s work is one of the most suited to being made big. In work where a manga influence is most visible, her dramatic curves, bold colours, and sense of speed have a cinematic quality. Often rightly referred to as an artist that makes a special effort to represent realistic body types, she also discusses in her interview about the importance of including characters who are disabled in her narratives. Espinosa notes that her installation was intended to represent transformative and healing processes. For this, she presents a character racing into a tube and coming out at the end of it transformed into a giant pink superheroine, referencing the themes that she explored in her recent book Hoops.

Conxita Herrero mentions her interest in formal experimentation within the zine format, and the sheer amount of zines she’s produced is impressive. The physical process of comics making is what her installation focuses on. On one wall there’s a self-portrait painting, on another, there’s a screen that slides through various pages, and her desk sits to one side while her chair, lamp, and pencils climb up the wall in an act of defiance against gravity.

Like all the artists here (as far as I can tell), Miriam Muñoz’s (aka Miriampersand) income comes more from commercial commissions than books, and her ability to confidently move between styles no doubt helps. Miriampersand’s big piece is a gateway/portal sitting upon a reflective floor with a frame that on one side presents the story of a crocodile moving through a blue-toned water world and on the other through a burnt orange desert one. Visitors are encouraged to open the door and pass through this gateway themselves.

Nadia Hafid provides one of the best examples of cartooning as a process of reduction and storytelling as a deconstruction of moments. Her debut book El buen padre isn’t just about formal experimentation, it’s also rooted in her interests in migration and people living in society’s periphery, and she portrays these people with stunning sequences that draw focus to body language and emotion. Her installation, said to describe the process of creative inspiration, depicts a woman in a room moving from reading to writing, with lighting used to “tell” this story temporally.

Hola Siri is an impressive self-published comic in which Marta Cartu tells the story of lives surrounded by digital technology with page layouts which themselves are informed by the software and digital design. It’s no surprise that in her interview she states that she is “thinking about how the comic itself is narrated.” Having made installations before with the hyperactive qualities of digital life, for Graphic Constellation Cartu looks to the biological world for inspiration. Her hanging panels, between which the visitor can meander and order into a loose narrative, depict hyphae, which the exhibition texts tells us are “the most basic structural unit that makes up the body of fungi and they function like a network of filaments that grow in an interconnected manner,” similar to how the individual panel is part of a network that interconnects with all the other panels in a comic.

The show concludes with two of the biggest names in Spanish comics and illustration at the present moment, Ana Galvañ and Maria Medem. Galvañ’s work, originally published by Apa Apa, has been getting translated over recent years, and both artists’ distinctive styles are popular with magazine editors and book publishers alike. Galvañ was one of the few female artists to be featured in Fantagraphics’ Spanish Fever anthology back in 2016. Despite the general rise in popularity of these artists, in her interview Galvañ levels some criticism at the cultural coverage in national papers, calling them out for being somewhat closed-minded gatekeepers, which is an issue that plagues nearly everywhere. Her installation doesn’t lean into the constructivist influences as much as I’d have predicted, she instead opts to showcase a largescale print of a new short story, surrounded by sculptural representations of elements within the comic.

It’s amazing to hear that Maria Medem failed a course at art school because of a comic she produced (it would be published in Galvañ’s Tik Tok zine). It’s Medem’s mythical and surrealist animations that most captivated me in her room. The most telling revelation in her interview is the influence of photographers Cristina García Rodero and Atín Aya, two documentarians of the persistence of tradition in Spanish culture and also the expansive desert landscapes that can be found throughout the country. Alluding to this influence, Medem’s installation is a minimal and restrained piece featuring two white sheets on which are embroidered a story of a prayer and response. Dried flowers hang from the rope (a hint of some ancient custom perhaps), a faux stone lies idly, and the backdrop is a lightbox set in dusky tones. It very much feels like you’re stepping into a memory of some distant and rural life.

What each of these artists and their installations does is not an abstraction of comics from their typical book format but an abstraction of how comics work at a fundamental level. They place these fundamental elements of comics making process into conversation with games, interactive technology, sculpture, biology, the natural landscape, and much more, each providing examples of how experiences of these phenomena can be remediated in ways that draw attention to them in surprising ways. This approach to exhibiting comics artists doesn’t fetishize comics by commodifying them or making them rarified, but rather expands our intuitive understanding of what exactly these artists are doing when they tell a story on a page using the medium’s conventions.

Graphic Constellation not only provides ample evidence that the Spanish comics scene is bursting with talent, but it also provides an example of exactly how comics artists and comics themselves can be understood as an artistic process and art that doesn’t need to play by the same rules as their fine art relatives. And when curators start to approach comics in this way, exhibitions are born that fully deserve the attention that the public will hopefully give them.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply